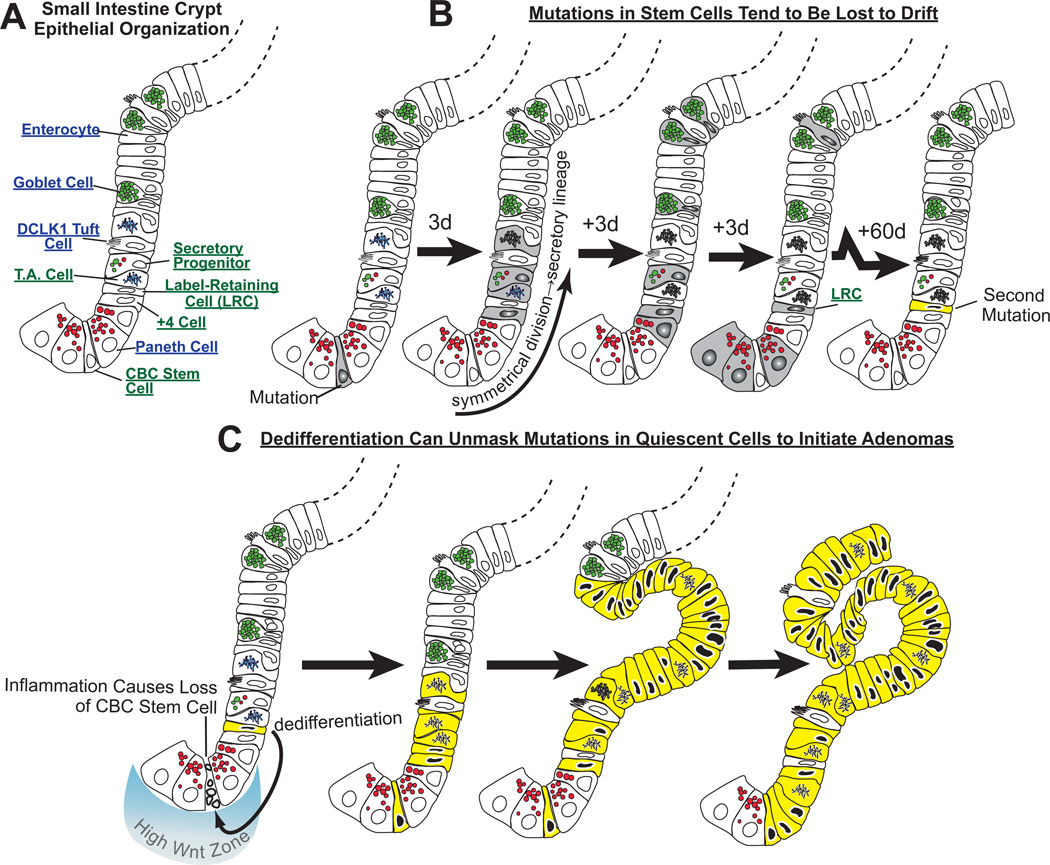

Fig. 3. Neoplastic growth in the intestines may occur because dedifferentiation of long-lived mature cells unmasks mutations.

A) Some of the key cell lineages in the cartoon of one side of a crypt are labeled. B) Mutations occurring in a crypt base columnar (“CBC”) stem cell may be lost by drift into differentiated cells, because CBC cells divide frequently and often symmetrically to produce two daughters that differentiate. Here, a CBC cell has acquired a mutation and has undergone symmetrical division such that both daughter cells differentiate along the secretory lineage. The progeny, depicted in time intervals (e.g., “3d” ≈3 days elapsed) differentiate into goblet, Paneth, tuft and enteroendocrine (not depicted) cells. With time, most of those cells die, at which point, the mutation will be lost, were it not for the fact that some longer lived cells (e.g., Paneth cells or perhaps even longer-lived “label-retaining cells”) could potentially harbor the mutation for months. In the case depicted, the Paneth cells are also lost to normal turnover, but the even longer living LRC in this unit acquires an additional mutation over the two months following the first mutation in the stem cell. C) Again, that mutation would likely be lost as even the LRC ages and dies, unless, as is shown at the bottom, inflammation causes death of the normal, constitutively active stem cell in the crypt. Here, CBC death induces the LRC, which has accumulated an additional mutation, to dedifferentiate, become exposed to high Wnt signaling and reenter the cell cycle. The mutations in the LRC are now unmasked as the cell is exposed to the high Wnt environment and begins to proliferate. The mutations prevent the cell from differentiating beyond the transit amplifying stage, and a clone of early neoplastic cells derived from this mutant stem cell develops an adenoma. The key aspect of this model is that the normal CBC divides too rapidly to accumulate mutations, whereas differentiated cells live longer and can store mutations that may affect proliferation or differentiation but won’t affect these quiescent cells until dedifferentiation unmasks them.