Abstract

Objective

CT, an important diagnostic tool in the emergency department (ED), might increase the ED length of stay (LOS). Considering the issue of ED overcrowding, it is important to evaluate whether CT use delays or facilitates patient disposition in the ED.

Design

A retrospective 1-year cohort study.

Setting

5 EDs within the same healthcare system dispersed nationwide in Taiwan.

Participants

All adult non-trauma patients who visited the 5 EDs from 1 July 2011 to 30 June 2012.

Interventions

Patients were grouped by whether or not they underwent a CT scan (CT and non-CT groups, respectively).

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The ED LOS and hospital LOS between patients who had and had not undergone CT scans were compared by stratifying different dispositions and diagnoses.

Results

CT use prolonged patient ED LOS among those who were directly discharged from the ED. Among patients admitted to the observation unit and then discharged, patients diagnosed with nervous system disease had shorter ED LOS if they underwent a CT scan. CT use facilitated patient admission to the general ward. CT use also accelerated patients' admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) for patients with nervous system disease, neoplasm and digestive disease. Finally, patients admitted to the general wards had shorter hospital LOS if they underwent CT scans in the ED.

Conclusions

CT use did not seem to have delayed patient disposition in ED. While CT use facilitated patient disposition if they were finally hospitalised, it mildly prolonged ED LOS in cases of patients discharged from the ED.

Keywords: emergency department, patient flow, length of stay

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study was conducted across the largest healthcare system in Taiwan, which receives 8–10% of the national health insurance budget, according to government statistics. The study sites were geographically well dispersed nationwide.

The very large sample size, with 293 426 emergency department (ED) visits, enabled assessment of multiple potential factors to estimate the influence of CT utilisation on patient flow in the ED.

The study sites belonged to the same healthcare system, potentially limiting the implications of the conclusions.

Introduction

CT utilisation has grown rapidly due to its recognised clinical value in nearly all areas of medicine, a trend enabled by technological advances and widespread availability. The utilisation of CT scanning in the acute setting nearly tripled from 1996 to 2010.1 At the same time, the relatively high-radiation doses associated with CT have also raised health concerns.2–4 Multiple factors have contributed to the increase in CT use, such as increased availability and speed of obtaining CT, or possible patient expectations. Whether or not CT scans help disposition of patients in the emergency department (ED) is still controversial. Some studies have stated that CT use might not affect patient outcomes.5–8 However, other studies have suggested that CT use may reduce the time to disease diagnosis, improve clinical outcome and help patient disposition. For instance, the proportion of ED visits with a diagnosis of pulmonary embolism has increased significantly, and this rise can be attributed in large part to the increased availability and use of CT.9 Ng et al10 reported that early abdominopelvic CT for acute abdominal pain may reduce mortality. Systermans et al11 suggested that abdominal CT scans frequently resulted in a change in the clinical diagnosis and patient disposition. Kocher et al12 stated that the increased use of CT in the ED was associated with a decline in admissions and transfers. Since ED overcrowding has become an international health issue,13 14 it is important to evaluate whether use of CT delays or facilitates patient disposition in the ED. However, it is very hard to evaluate the influence of CT use on patient throughput because of several variables that affect patient disposition. A previous study has stated that the indirect effect of CT use may be increased length of stay (LOS) in the ED.15 It is oversimplistic to compare the average ED LOS of patients who have and have not undergone CT. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to investigate the influence of CT utilisation on ED patients' flow with ED LOS as the outcome variable by stratifying patients with different dispositions and diagnoses.

Methods

Study design

This was a retrospective 1-year cohort study. Patient records and information were anonymised and de-identified prior to analysis.

Study setting and population

This study was conducted across the largest healthcare system in Taiwan, which receives 8–10% of the national health insurance budget, according to government statistics. From 1 July 2011 to 30 June 2012, five EDs within this healthcare system were involved in the study. The five EDs were geographically well dispersed nationwide. Two EDs were tertiary referral medical centres with over 3500 and 2500 beds, respectively. The other three were secondary regional hospitals with over 1200, 1000 and 250 beds, respectively. All the EDs, except the smallest, were the largest in their counties. The cumulative number of mean annual visits in the five EDs was over 480 000 per year. All adult non-trauma patients who presented to the EDs within the study period were included. Except for the hospital capacity, the five EDs had no difference in services provided, staffing and equipment. CT scan was available 24 h every day in these five EDs.

Study protocol

All ED patients in the five hospitals were divided into CT group (patients who had undergone at least one CT scan during ED stay) and non-CT group (patients who had not undergone any CT scan during ED stay). Patient demographic factors, including age, sex, visit characteristics (triage category, time of arrival, disposition, ED LOS and hospital LOS), hospital factors (hospital type and treating physician) and diagnoses, were obtained from the ED administrative database and studied in reference to CT utilisation. Times of arrival were divided into morning shift (8:00–16:00), evening shift (16:00–00:00) and night shift (00:00–8:00). The dispositions included discharge, admission to the observation room and then discharge, admission to the general ward, admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) and ED mortality. There were observation rooms in all five EDs of this study. Two kinds of patients were admitted to the observation units: (1) patients who had no definite diagnosis were admitted to the observation unit so that they could be observed for any change in their clinical status; (2) patients who were waiting for hospitalisation were also admitted to the observation units. Therefore, some patients in the observation rooms were discharged, and others were admitted to the hospital. Patients transferred to other hospitals for admission were categorised as admitted; those discharged against medical advice or outpatient transference were categorised as discharged. Triage category was defined according to the five-level Taiwan Triage and Acuity Scale, formulated by the Department of Health in Taiwan. According to these criteria, cases identified as triage levels 1 and 2 should be attended to immediately or within 10 min, respectively, and are defined as urgent. Cases with triage levels 3, 4 and 5 should be assessed within 30, 60 or 120 min, respectively, and are classified as non-urgent.16 Diagnoses were grouped into categories using the diagnostic codes from the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM).

Measures

Patient dispositions and ED LOS were documented as the primary outcomes. The ED LOS was defined as the period from the initial presentation of the patient to the ED, as documented by the triage nurse, to the discharge of the patient from the ED. ED LOS was calculated as the following five points: discharge from the ED, discharge from the observation room, admission to the general ward, admission to the ICU and ED mortality. The hospital LOS of patients who were admitted to the general ward or ICU was documented as secondary outcome to evaluate the prognosis of patients.

Data analysis

The patient age, ED LOS and hospital LOS were reported as means with standard deviations (SDs), and analysed by Student's t test. The distribution of category demographic factors including patient sex, visit characteristics (triage category, time of arrival), hospital factors (hospital type and treating physician) and diagnoses, was presented as numbers and percentages. χ2 Tests were used to evaluate the association between these parameters and CT utilisation.

To analyse the influence of CT utilisation on ED LOS and hospital LOS, multivariable linear regression was applied after adjusting for potential confounding factors including patient age and sex, visit characteristics (triage category, time of arrival) and hospital factors (hospital type and treating physician).

To further reduce the heterogeneity between the study and control group, propensity score (PS) matching was also used to control for potential confounding factors. The advantage of the PS matching method is the two-step analysis design, which enables a balance of possible confounding factors between the treated and control groups before ‘seeing’ the results in the first step of the analysis. The PS of a patient's probability of undergoing a CT scan was calculated according to multiple individual characteristics, including patient age and sex, visit characteristics (triage category, time of arrival) and hospital factors (hospital type and treating physician) stratified with different diagnosis categories via a logistic regression model in the first step of the analysis. Different PS matching methods were considered, including exact, subclassification, nearest neighbour, optimal and generic matching.17 18 Nearest neighbour matching without replacement, with a ratio of 1:4 for all diagnosis categories except nervous system disease (1:1), was chosen based on the per cent balance improvement, defined as improvement of the mean difference between groups before and after matching. Then, the ED LOS and hospital LOS were compared again between the matching groups, with linear regression.

All analyses were two tailed and p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. SPSS V.12.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA) and R (V.3.0.2; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) were used for all statistical analyses.

Results

During the 1-year study, 293 426 adult non-trauma patients visited the five EDs. Among them, 11.4% of patients underwent CT scans. Of these patients ongoing a CT scan during the ED stay, 95.9% underwent one CT scan, 3.7% underwent two CT scans and 0.4% underwent three or more CT scans. Patient demographic factors, including age, sex, visit characteristics (triage category, time of arrival), hospital factors (hospital type and treating physician), diagnoses, dispositions, ED LOS and hospital LOS of the two study groups are compared in table 1. The continuous variables (age, ED LOS, hospital LOS) were analysed by Student's t test, and all other category variables were analysed by χ2 test. The CT scans were most frequently used in the diagnoses of nervous system disease (ICD-9-CM: 320–389 and 430–438), followed by gastrointestinal disease (ICD-9-CM: 520–579), genitourinary disease (ICD-9-CM: 580–629), pulmonary disease (ICD-9-CM: 460–519), neoplasms (ICD-9-CM: 140–239) and cardiovascular disease (ICD-9-CM: 390–429 and 439–459). CT scans for these six disease categories accounted for 77.1% of the total CT scans performed in the five EDs.

Table 1.

Patients' basic demographic factors

| CT used (33 336) |

CT not used (260 090) |

p Value* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 60.5 | ±18.34 | 53.7 | ±19.67 | <0.001 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 18 101 | 54.3% | 129 005 | 49.6% | <0.001 |

| Female | 15 235 | 45.7% | 131 085 | 50.4% | |

| Triage | |||||

| Urgent | 10 428 | 31.3% | 42 853 | 16.5% | <0.001 |

| Non-urgent | 22 908 | 68.7% | 217 237 | 83.5% | |

| Time of arrival | |||||

| 8:00–16:00 | 15 172 | 45.5% | 103 630 | 39.8% | <0.001 |

| 16:00–00:00 | 13 146 | 39.4% | 102 392 | 39.4% | |

| 00:00–8:00 | 5018 | 15.1% | 54 068 | 20.8% | |

| Physician | |||||

| Visit staff | 21 051 | 63.1% | 162 100 | 62.3% | 0.003 |

| Resident | 12 285 | 36.9% | 97 990 | 37.7% | |

| Hospital | |||||

| Centre | 21 523 | 64.6% | 147 499 | 56.7% | <0.001 |

| Regional | 11 813 | 35.4% | 112 591 | 43.3% | |

| Disposition | |||||

| Discharge from ED | 8246 | 24.7% | 146 539 | 56.30% | <0.001 |

| Discharge from observation room | 6607 | 19.8% | 47 831 | 18.40% | |

| Admission to general ward | 15 682 | 47.0% | 58 988 | 22.70% | |

| Admission to ICU | 2557 | 7.7% | 5175 | 2.00% | |

| ED mortality | 244 | 0.7% | 1557 | 0.60% | |

| Diagnostic category | |||||

| Nervous | 11 724 | 35.2% | 25 208 | 9.7% | <0.001 |

| Gastrointestinal | 6671 | 20.0% | 61 229 | 23.5% | |

| Genitourinary | 2213 | 6.6% | 25 795 | 9.9% | |

| Pulmonary | 1911 | 5.7% | 44 782 | 17.2% | |

| Neoplasms | 1714 | 5.1% | 10 501 | 4.0% | |

| Cardiovascular | 1456 | 4.4% | 17 914 | 6.9% | |

| Others | 7647 | 22.9% | 74 661 | 28.7% | |

| ED LOS (h) | 16.6 | ±27.13 | 13.0 | ±27.28 | <0.001 |

| Hospital LOS (day) | 12.7 | 14.44 | 12.5 | 12.99 | <0.001 |

*Continuous variables (age, ED LOS and hospital LOS) were analysed by Student's t test, and all other category variables were analysed by χ2 test. A p value <0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

ED, emergency department; ICU, intensive care unit; LOS, length of stay.

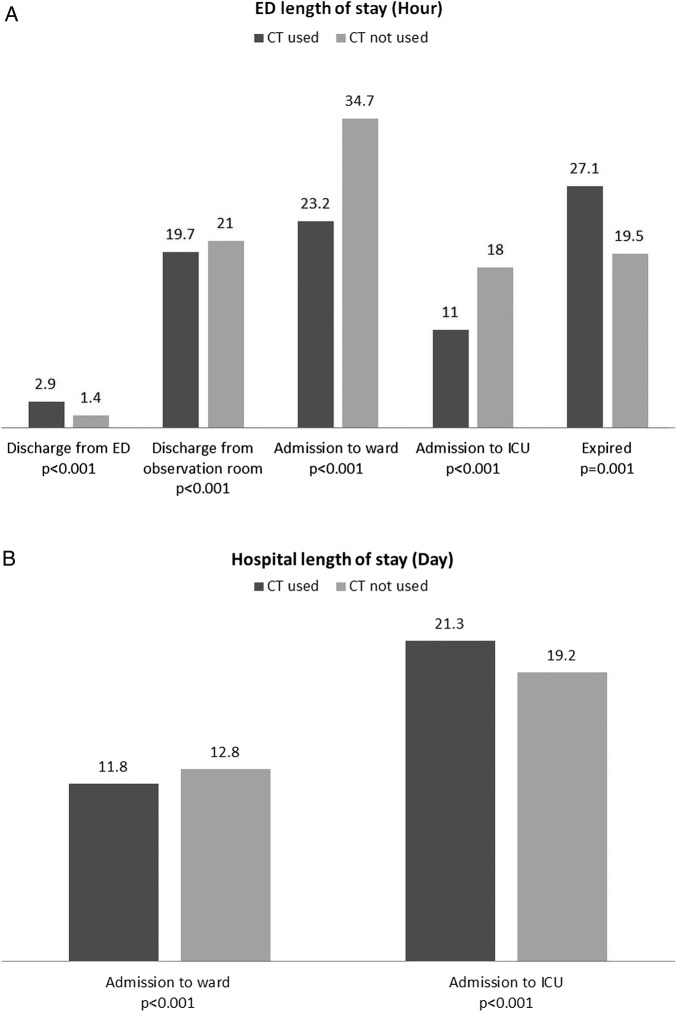

In the non-CT group, 24.7% of patients were hospitalised after ED visits (including 22.7% admitted to the general ward and 2.0% admitted to the ICU). In the CT group, 54.7% of patients were hospitalised after ED visits (including 47.0% admitted to the general ward and 7.7% admitted to the ICU). The hospitalisation rate among patients in the CT group was higher than that among patients in the non-CT group. The overall ED LOS for patients in the CT group was longer than that for patients in the non-CT group (16.6 vs 13.0 h). However, after stratifying by disposition, patients who were discharged from the ED and who had undergone a CT scan tended to have longer ED LOS, while those discharged from the observation rooms or who were admitted to the general ward or ICU had shorter LOS (figure 1A). The hospital LOS for patients in the CT group who were admitted to the general ward was shorter than that for patients in the non-CT group, but the hospital LOS for patients in the CT group who were admitted to the ICU was longer than that for patients in the non-CT group (figure 1B).

Figure 1.

(A) ED length of stay (hour) and (B) hospital length of stay (day) of different dispositions in the CT and non-CT groups. ED, emergency department; ICU, intensive care unit.

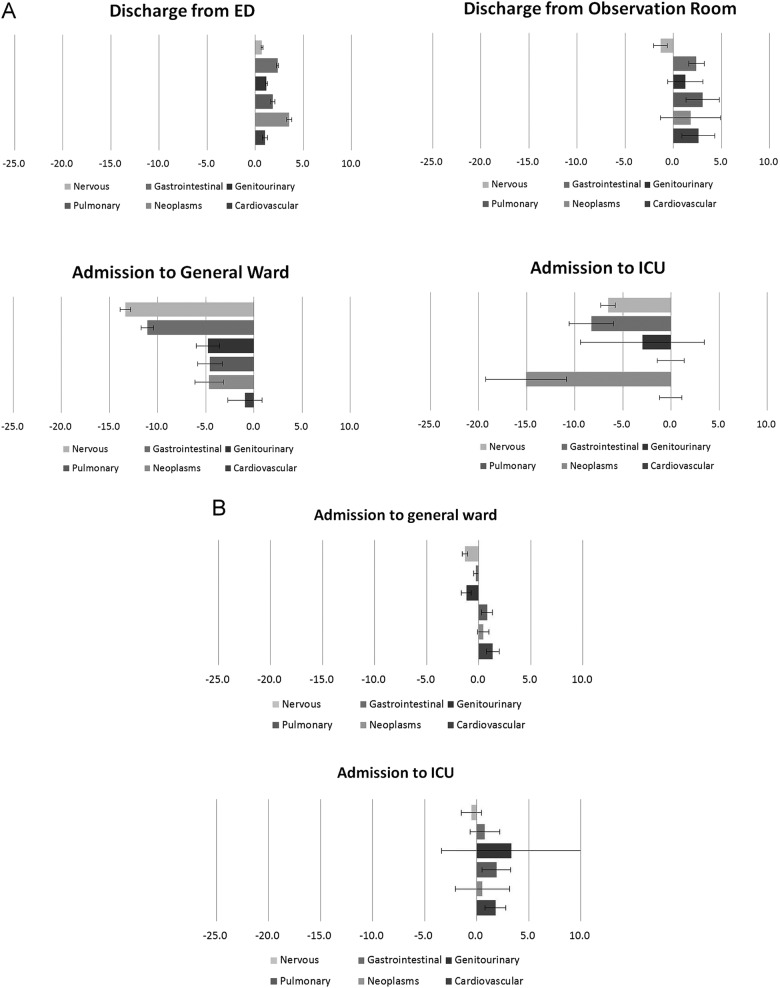

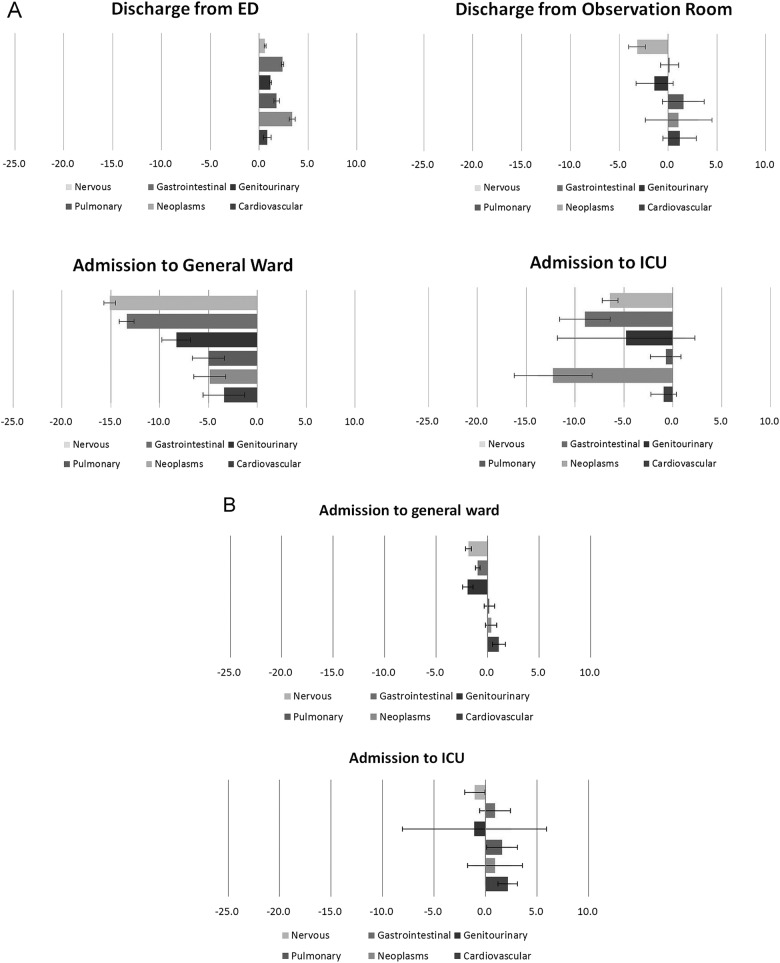

Linear regression was used to analyse the impact of CT on ED LOS and hospital LOS in different diagnostic groups, after adjusting for potential confounding factors, including patient age and sex, visit characteristics (triage category, time of arrival) and hospital factors (hospital type and treating physician) in the multivariable regression model (figure 2A,B), and PS matching regression model (figure 3A,B). With regard to patients discharged from the ED, CT prolonged ED LOS in the six diagnostic groups. Among patients discharged from the ED, patients who had undergone CT scans spent more time in the ED than patients who had not undergone CT scans in all six diagnosis categories in both the multivariable regression model and the PS matching regression model. Among patients discharged from the observation room, those diagnosed with nervous system disease had shorter ED LOS in both models, but those diagnosed with gastrointestinal disease, pulmonary disease and cardiovascular disease had prolonged ED LOS after undergoing CT scan, in the multivariable regression model but not in the PS matching regression model. Among patients admitted to the general ward, CT use tended to shorten ED LOS, except among those who were diagnosed with cardiovascular disease, in the multivariable regression model; however, in the PS matching regression model, CT use tended to shorten ED LOS in all six diagnosis categories. Among patients who underwent CT scans and were then admitted to the ICU, those diagnosed with nervous system disease, neoplasm and gastrointestinal disease had shorter ED LOS in both models. With regard to hospital LOS among patients admitted to the general ward, CT use tended to shorten hospital LOS in patients diagnosed with nervous system disease, gastrointestinal disease and genitourinary disease, in both models. CT scan use did not influence hospital LOS among patients admitted to the ICU.

Figure 2.

Influence of CT utilisation on (A) ED length of stay (hours) and (B) hospital length of stay (day) in different diagnostic groups, adjusting for potential confounding factors, including patient's age, sex, visit characteristics (triage category, time of arrival) and hospital factors (hospital type and treating physician), by multivariable linear regression. ED, emergency department; ICU, intensive care unit.

Figure 3.

Influence of CT utilisation on (A) ED length of stay (hour) and (B) hospital length of stay (day) in different diagnostic groups, adjusting for potential confounding factors, including patient's age, sex, visit characteristics (triage category, time of arrival) and hospital factors (hospital type and treating physician), by propensity matching linear regression. ED, emergency department; ICU, intensive care unit.

Discussion

This study found that the overall rate of CT use in the five EDs was 11.4% (12.7% in medical centres and 10.4% in regional hospitals). According to a previous study in the USA, approximately one in seven patients who had made an ED visit up to 2007 had undergone a CT scan.12 While there is a trend of increased CT use in the ED, the rate of CT use in this study was somewhat lower than that reported in the USA. The study revealed that CT use was associated with patient age and sex, time of arrival, clinical urgency, hospital setting and treating physician. Furthermore, CT use was more prominent among elderly and male patients. Patients visiting the ED with urgent clinical presentation at triage had a greater chance of undergoing CT scans. The reason why patients who visited medical centres were more likely to receive CT scans might be related to clinical complexity. The rate of CT use during evening and night shifts was lower than that during the day shift. This might be because during outpatient clinic off-hours, patients visited the ED for relatively non-urgent problems; therefore, there was a lower proportion of CT use.

CT plays an important role in the diagnosis and disposition of patients with acute and sometimes life-threatening illnesses. However, according to a previous study, the indirect effect of CT use may be increased LOS in the ED.15 Overall, the mean ED LOS for patients who underwent CT scans was longer than that for patients who did not; however, it is oversimplistic to compare the average ED LOS of patients who have and have not undergone CT scans. According to the study, using CT scan to confirm diagnosis may delay patient discharge by an average of 1½ h, but it could accelerate patient admission to the general ward and ICU by an average of 11½ and 7 h, respectively; moreover, it decreased 1 day of hospital stay in general wards after hospital admission. In other words, prolonged LOS mainly occurred among patients who were directly discharged from the ED. However, if patients were ever admitted to the observation room before discharge, CT use shortened the ED LOS in patients with nervous system disease, and no significant difference was noted for the other five diagnosis categories. When CT scans were utilised, patients diagnosed with nervous system disease, neoplasm, gastrointestinal disease, genitourinary disease, pulmonary disease and cardiovascular disease, who were admitted to the general ward, had shorter ED LOS, and those diagnosed with nervous disease, neoplasm and digestive disease, who were admitted to the ICU, had shorter ED LOS. In addition to the ED LOS, CT scan in the ED shortened the total hospital LOS in nervous system disease, gastrointestinal disease and genitourinary disease after admission to general wards.

The reason why CT scan facilitated patient disposition might be that it shortened the diagnostic process.13 14 Systermans et al11 reported that abdominal CT scans frequently changed the clinical diagnosis and patient disposition. In addition, they reported that the rate of pulmonary embolism diagnosis in the ED increased significantly along with the increased availability and use of CT.9 Hoffmann et al19 suggested that early coronary CT angiography might significantly improve patient management in the ED. According to the study, the acceleration of the diagnostic process was more predominant in patients diagnosed with nervous disease. Unlike other diagnostic groups, CT use accelerated admittance of these patients to the general ward, as well as shortened the LOS of patients who were discharged from the observation room. According to our clinical experience, some patients presented to the ED with non-specified neurological symptoms such as dizziness, vertigo, or headache, without obvious focal neurological deficit, and were kept in the observation room to await symptom relief. When life-threatening conditions can be ruled out based on the CT findings, physicians might be more confident to allow patient discharge, which will shorten the LOS. ED overcrowding is a worldwide problem; thus, it is important to facilitate patient disposition by speeding up the diagnostic process. Conversely, CT use delayed patient discharge from the ED, but without CT to rule out life-threatening problems, more patients might be hospitalised for observation.12 This further exhausts the limited hospital capacity and exacerbates the issue of ED overcrowding. To improve the diagnostic process, adherence to established guidelines and best practices would increase the speed of diagnosis and ED disposition.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the five study sites belonged to the same healthcare system, potentially limiting the implications of the conclusions. For example, the LOS in these EDs is much longer than those in other EDs worldwide, and certainly within EDs in the USA and Western Europe. These differences may be explained by different definitions of observation and differences in the healthcare economics, patient expectations, or provider practice patterns. This may limit the generalisability of the current study. Second, patients were grouped by ICD-9-CM and not according to the symptom. On the other hand, the CT type, including the scan position and use of contrast, was unknown; hence, it was not possible to evaluate the reasons for CT use in any individual patient. Third, due to the limitations of the retrospective design, there might be some confounding factors that were not measured in this analysis that could influence patient hospitalisation or ED LOS. Further prospective studies are needed to determine the relationship between CT use and patient flow.

Conclusion

According to this study, CT scans did not seem to have delayed patient disposition in ED. While CT use facilitated patient disposition if patients were finally hospitalised, it mildly prolonged ED LOS for patients discharged from the ED.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Kaohsiung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital for supporting this research by making substantial contributions to acquisition of data (CMRP-G8C0361).

Footnotes

Funding: This study was supported in part by research grants from the Kaohsiung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Chang Gung Medical Foundation Institutional Review Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Smith-Bindman R, Miglioretti DL, Johnson E et al. Use of diagnostic imaging studies and associated radiation exposure for patients enrolled in large integrated health care systems, 1996-2010. JAMA 2012;307:2401–9. 10.1001/jama.2012.5960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pearce MS, Salotti JA, Little MP et al. Radiation exposure from CT scans in childhood and subsequent risk of leukaemia and brain tumours: a retrospective cohort study. JAMA 2012;380:499–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sodickson A, Baeyens PF, Andriole KP et al. Recurrent CT, cumulative radiation exposure, and associated radiation-induced cancer risks from CT of adults. Radiology 2009;251:175–84. 10.1148/radiol.2511081296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brenner DJ, Hall EJ. Computed tomography—an increasing source of radiation exposure. N Engl J Med 2007;357:2277–84. 10.1056/NEJMra072149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Korley FK, Pham JC, Kirsch TD. Use of advanced radiology during visits to US emergency departments for injury-related conditions, 1998-2007. JAMA 2010;304:1465–71. 10.1001/jama.2010.1408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tabas JA, Hsia RY. Invited commentary—emergency department neuroimaging: are we using our heads?: comment on “Use of neuroimaging in US emergency departments”. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:262–4. 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith-Bindman R, Aubin C, Bailitz J et al. Ultrasonography versus computed tomography for suspected nephrolithiasis. N Engl J Med 2014;371:1100–10. 10.1056/NEJMoa1404446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitsunaga MM, Yoon H-C. Head CT scans in the emergency department for syncope and dizziness. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2015;204:24–8. 10.2214/AJR.14.12993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schissler AJ, Rozenshtein A, Schluger NW et al. National trends in emergency room diagnosis of pulmonary embolism, 2001–2010: a cross-sectional study. Respir Res 2015;16:44 10.1186/s12931-015-0203-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ng CS, Watson CJE, Palmer CR et al. Evaluation of early abdominopelvic computed tomography in patients with acute abdominal pain of unknown cause: prospective randomised study. BMJ 2002;325:1387–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Systermans BJ, Devitt PG. Computed tomography in acute abdominal pain: an overused investigation? ANZ J Surg 2014;84:155–9. 10.1111/ans.12360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kocher KE, Meurer WJ, Fazel R et al. National trends in use of computed tomography in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 2011;58:452–62. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.05.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun BC, Hsia RY, Weiss RE et al. Effect of emergency department crowding on outcomes of admitted patients. Ann Emerg Med 2013;61:605–11. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.10.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pines JM, Hilton JA, Weber EJ et al. International perspectives on emergency department crowding. Acad Emerg Med 2011;18:1358–70. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01235.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stiell IG, Catherine CM, Rowe BH et al. Comparison of the Canadian CT head rule and the New Orleans Criteria in patients with minor head injury. JAMA 2005;294:1511–18. 10.1001/jama.294.12.1511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ng CJ, Yen ZS, Tsai JC et al. Validation of the Taiwan Triage and Acuity Scale: a new computerised five-level triage system. Emerg Med J 2011;28:1026–31. 10.1136/emj.2010.094185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rubin DB, Thomas N. Matching using estimated propensity scores: relating theory to practice. Biometrics 1996;52:249–64. 10.2307/2533160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stuart EA, Lee BK, Leacy FP. Prognostic score-based balance measures can be a useful diagnostic for propensity score methods in comparative effectiveness research. J Clin Epidemiol 2013;66(8 Suppl):S84–90.e1. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.01.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoffmann U, Bamberg F, Chae CU et al. Coronary computed tomography angiography for early triage of patients with acute chest pain: the ROMICAT (Rule Out Myocardial Infarction using Computer Assisted Tomography) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 53:1642–50. 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.01.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]