Case presentation

A previously healthy 19-year old female presented to the gynaecological clinic with gradual abdominal distension for six months, associated with progressive abdominal discomfort. There was no history of nausea, vomiting, weight loss, or anorexia. She reported no changes in bowel habits and denied genitourinary symptomatology. Menarche occurred at 14 years of age, and her menstrual periods had always been regular. She denied recent sexual activity and was not currently taking oral contraceptives. The remainder of the patient's history, including a focused family history, was non-contributory.

Physical examination revealed the presence of a somewhat firm, irregular, nontender, and mobile mass arising from the pelvis, corresponding in size to a pregnant uterus of 24 weeks' gestation.

Laboratory analysis showed a blood haemoglobin concentration of 12.6 g/dL. The remainder of her laboratory results were within physiological parameters, and pregnancy was excluded.

Transabdominal ultrasonography revealed globular uterine enlargement and a hypoechoic mass measuring 18 cm × 14 cm. The ovaries and adnexa were not visualized because they were obscured by the enlarged, bulky uterus. Neither ascites nor hydronephrosis was noted. The patient was counselled about the diagnosis of uterine fibroid and underwent exploratory laparotomy after proper counselling and written informed consent.

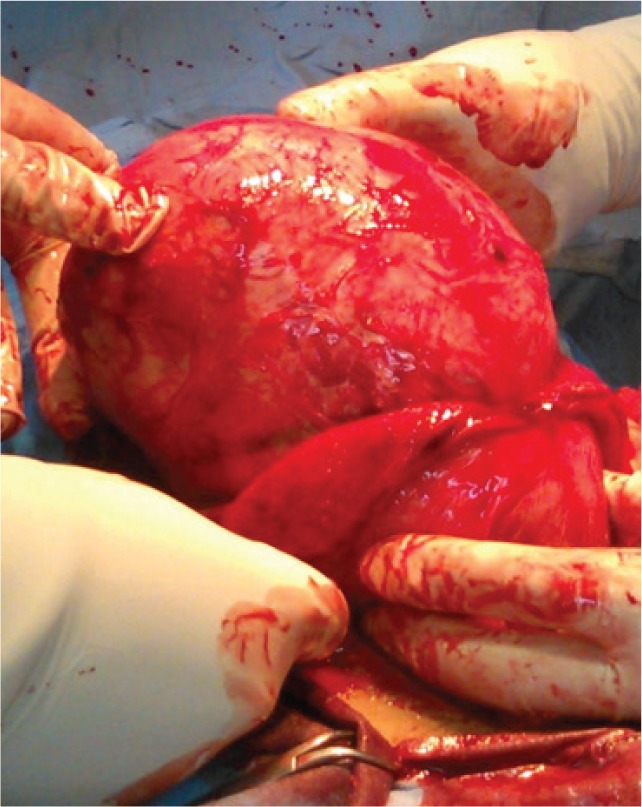

Intraoperatively, the uterus was grossly enlarged by a large fibroid measuring 16 cm x 10 cm (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Both ovaries and fallopian tubes were normal.

Figure 1.

Intraoperative image of the exteriorized uterus, showing the large fundal leiomyoma

Figure 2.

Excised leiomyoma after myomectomy

The uterus was elevated out of the abdominal cavity and myomectomy of the large tumour was achieved through a fundal incision. The excision site was closed with continuous catgut sutures, and the abdomen was closed in layers. Cut section of the gross specimen revealed whitish nodules with a whorled appearance and fibroelastic consistency suggestive of benign leiomyoma (Figure 3). The specimen was sent for formal histopathology. Results of histopathological examination confirmed the diagnosis of a benign fibroid of the uterus.

Figure 3.

Sectional view of excised leiomyoma, showing the typical nodular, whorled appearance, and fibroelastic consistency

The patient's postoperative course was uneventful, and she was discharged on postoperative day seven. A six-month follow-up with repeat ultrasonography was arranged. Counselling regarding recurrence and future fertility was offered before discharge. Though our client was an adolescent and denied being sexually active, she was offered family planning counselling and advised not to conceive for at least one year to allow wound healing and full recovery.

Discussion

Uterine leiomyomas (also called fibroids) are benign growths that represent the most common neoplasms of the uterus, affecting 20% to 30% of women between the ages of 30 and 50 years.1–4 Their occurrence in the adolescent population (under the age of 20 years) is infrequent and relatively few cases have been documented in the literature.5–12

The aetiology of leiomyomas in adolescents and adults is generally unknown, but leiomyomas are known to grow in response to both oestrogen and progesterone stimulation, and their prevalence increases throughout the reproductive years and is markedly reduced after menopause.5–8 Higher concentrations of oestrogen and progesterone receptors, as well as aromatase, have been observed in fibroids compared to normal myometrial tissue.13–15 Early menarche, exposure to exogenous oestrogen, obesity, and pregnancy usually influence fibroid growth.5–8 Pregnancy and obesity were excluded in our patient as well as any history of administration of hormonal agents. Our patient admitted to being a regular consumer of red meat and broiler chickens. Some experts have linked the consumption of red meat and broiler chickens (possible sources of exogenous steroids) with the growth of fibroids in younger women, but there is a lack of published evidence to support this hypothesis.

A genetic component of the pathogenesis of uterine fibroids has also been suggested.16,17 High-frequency mutations involving chromosomes 6, 7, 12, and 14 have been reported in uterine leiomyomas.16,17 It is not known, however, how these mutations initiate the cascade of events that eventually leads to the formation of a fibroid. Some theorists suggest that intrinsic myometrial anomalies and endometrial injury play important roles. This is a plausible explanation of fibroid formation among menstruating adolescents, but it falls short of explaining why some lesions appear sooner rather than later in adult life.18,19 It is possible that these lesions are congenitally acquired and exist at early childhood only to develop as a result of sex steroid stimulation after menarche.20 Interestingly, a higher incidence of leiomyomas have been observed among African women, in whom uterine leiomyomas also tend to occur at a younger age, with increased size, and are more frequently associated with symptoms.21,22 There is evidence that the expression of abnormal genes accounts for increased severity of symptoms related to uterine leiomyomas among African women when compared to white women.22

The clinical presentation of symptomatic uterine leiomyomas in adolescents may include irregular uterine bleeding, pelvic pain, and pressure symptoms, such as urinary frequency or urgency.19 Our patient presented with a pelvic mass without any abnormal uterine bleeding, which explains the normal haemoglobin level on admission. Physicians should be aware of pelvic tumours, such as müllerian adenocarcinomas and sarcoma botryoides, which present as pelvic masses in adolescents.

The initial step in evaluating a woman with a pelvic mass is pelvic examination. If leiomyoma is suspected, the initial diagnostic adjunct should be ultrasonography, owing to its diagnostic accuracy, cost-effectiveness, and wide availability.4 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) represents the gold standard for the evaluation of pelvic soft tissue tumours; however, the technology is not widely available in lowresource settings.4 Computed tomography (CT) scanning is not recommended for the evaluation of uterine leiomyomas.23

The treatment algorithm for uterine leiomyomas depends on the patient's age and family planning goals, as well as tumour size and symptomatology. Asymptomatic leiomyomas can be kept under observation, with regular evaluation to eliminate the possibility of malignant transformation.24

There are no treatment guidelines for symptomatic fibroids in adolescents. Surgical treatments such as myomectomy, myolysis, and hysterectomy can be employed when appropriate. Myomectomy is a common procedure performed for young women with symptomatic leiomyomas; it preserves fertility, does not interfere with the hormonal milieu of the developing adolescent, and is associated with a low recurrence rate.19 Myomectomy can be performed by laparotomy, laparoscopy, or hysteroscopy, depending on the number, size, and location of the fibroids. Hysterectomy is often performed for women with symptomatic leiomyomas who do not desire to retain fertility.25

Medical treatments and minimally invasive procedures can be performed in some cases to allow a more rapid recovery.26 However, the use of such treatments in adolescents lacks supportive evidence and little is known about their applicability to this group.19

Uterine artery embolization (UAE) is an additional option. In this procedure, the ascending branches of the uterine artery supplying the leiomyomas are accessed and embolized to achieve complete loss of fibroid perfusion. This causes necrosis and shrinkage of the tumour.27 However, the potential complications associated with UAE (ovarian and fallopian tube damage resulting from impaired blood flow), may limit its applicability in adolescents who desire to retain fertility.28

Medical management is only used for short-term therapy because of the significant risks associated with long-term treatment. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists, selective oestrogen receptor modulators (SERMs), antiprogestins (RU486), and aromatase inhibitors have all been utilized.29 There is limited evidence available regarding the efficacy of these medical interventions for managing uterine leiomyomas in the adolescent population.

Management of symptomatic fibroids in adolescents can be challenging, with fertility preservation almost always a major priority, in addition to the patient's safety and physical well-being. Physicians should offer pre- and post-procedure counselling regarding future fertility, recurrence following treatment, family planning options, and the importance of early and frequent antenatal visits when pregnant, as well as early completion of family size. A high degree of suspicion is important when encountering an young woman with a pelvic mass. Pelvic examination and ultrasonography are crucial to establish the diagnosis. Myomectomy is the best procedure in the adolescent group, in view of preserving fertility.

Conclusions

Uterine leiomyomas should be considered in adolescent women presenting with a pelvic mass and abdominal pain. The management of leiomyomas in this age group should be conservative, with the goal of preserving fertility. Accurate evaluation of the aetiology of these tumours is important for future counselling.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all staff of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at Iringa Regional Hospital for their support in the preparation of this article.

References

- 1.Laughlin SK, Baird DD, Savitz DA, Herring AH, Hartmann KE. Prevalence of uterine leiomyomas in the first trimester of pregnancy: an ultrasound-screening study. Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Mar;113(3):630–635. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318197bbaf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen CR, Buck GM, Courey NG, Perez KM, Wactawski-Wende J. Risk factors for uterine fibroids among women undergoing tubal sterilization. Am J Epidemiol. 2001 Jan 1;153(1):20–26. doi: 10.1093/aje/153.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borgfeldt C, Andolf E. Transvaginal ultrasonographic findings in the uterus and the endometrium: low prevalence of leiomyoma in a random sample of women age 25–40 years. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000 Mar;79(3):202–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karasick S, Lev-Toaff AS, Toaff ME. Imaging of uterine leiomyomas. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992 Apr;158(4):799–805. doi: 10.2214/ajr.158.4.1546595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grapsa D, Smymiotis V, Hasiakos D, Kontogianni-Katsarou K, Kondi-Pafiti A. A giant uterine leiomyoma simulating an ovarian mass in a 16-year-old girl: a case report and review of the literature. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2006;27(3):294–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bekker G, Gavrilescu T, Rickets-Holcomb L, Puka-Khandam P, Akhtar A, Ansari A. Symptomatic fibroid uterus in a 15-year-old girl. Int Surg. 2004 Apr-Jun;89(2):80–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diesen DL, Price TM, Skinner MA. Uterine leiomyoma in a 14-year-old girl. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2008 Feb;18(1):53–55. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-989299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fields KR, Neinstein LS. Uterine myomas in adolescents: case reports and a review of the literature. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 1996 Nov;9(4):195–198. doi: 10.1016/s1083-3188(96)70030-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perkins JD, Hines RS, Prior DS. Uterine leiomyoma in an adolescent female. J Natl Med Assoc. 2009 Jun;101(6):611–613. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30954-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Michala L, Vlachos GD, Belitsos P, Antsaklis A. Uterine fibroid in an adolescent: an unlikely diagnosis? J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010 Feb;30(2):207–208. doi: 10.3109/01443610903494700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berveiller P, Mir O, Menu Y, Jamali M, Carbonne B. Fertility-sparing approach in a teenager with uterine tumor diagnosed as a sarcoma on imaging. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2010;69(3):157–159. doi: 10.1159/000264681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsili AC, Lentoudi ED, Argyropoulou MI, Dalkalitsis N, Batistatou A, Paraskevaidis E, et al. Fibromatous uterus in a 16-year-old girl: a case report. Case Rep Med. 2010;2010:932762. doi: 10.1155/2010/932762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rein MS, Barbieri RL, Friedman AJ. Progesterone: a critical role in the pathogenesis of uterine myomas. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995 Jan;172(1 Pt 1):14–18. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)90077-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brandon DD, Erickson TE, Keenan EJ, Strawn EY, Novy MJ, Burry KA, et al. Estrogen receptor gene expression in human uterine leiomyomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995 Jun;80(6):1876–1881. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.6.7775635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sumitani H, Shozu M, Segawa T, Murakami K, Yang HJ, Shimada K, et al. In situ estrogen synthesized by aromatase P450 in uterine leiomyoma cells promotes cell growth probably via an autocrine/intracrine mechanism. Endocrinology. 2000 Oct;141(10):3852–3861. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.10.7719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ligon AH, Morton CC. Leiomyomata: heritability and cytogenetic studies. Hum Reprod Update. 2001 Jan-Feb;7(1):8–14. doi: 10.1093/humupd/7.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ligon AH, Morton CC. Genetics of uterine leiomyomata. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2000 Jul;28(3):235–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parker WH. Etiology, symptomatology, and diagnosis of uterine myomas. Fertil Steril. 2007 Apr;87(4):725–736. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.01.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moroni RM, Vieira CS, Ferriani RA, Reis RM, Nogueira AA, Brito LG. Presentation and treatment of uterine leiomyoma in adolescence: a systematic review. BMC Womens Health. 2015 Jan 22;15:4. doi: 10.1186/s12905-015-0162-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Rooy CG, Wiegerinck MA. A 15-year-old girl with an expansively growing tumour. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1986 Sep;22(5–6):373–377. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(86)90128-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baird DD, Dunson DB, Hill MC, Cousins D, Schectman JM. High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in black and white women: ultrasound evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003 Jan;188(1):100–107. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marshall LM, Spiegelman D, Barbieri RL, Goldman MB, Manson JE, Colditz GA, et al. Variation in the incidence of uterine leiomyoma among premenopausal women by age and race. Obstet Gynecol. 1997 Dec;90(6):967–973. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(97)00534-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Casillas J, Joseph RC, Guerra JJ., Jr CT appearance of uterine leiomyomas. Radiographics. 1990 Nov;10(6):999–1007. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.10.6.2259770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lumsden MA. Modern management of fibroids. Obstet Gynaecol Reprod Med. 2013 Mar;23(3):65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Falcone T, Walters MD. Hysterectomy for benign disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(3):753–767. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318165f18c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seracchioli R, Rossi S, Govoni F, Rossi E, Venturoli S, Bulletti C, et al. Fertility and obstetric outcome after laparoscopic myomectomy of large myomata: a randomized comparison with abdominal myomectomy. Hum Reprod. 2000 Dec;15(12):2663–2668. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.12.2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Volkers NA, Hehenkamp WJ, Birnie E, de Vries C, Holt C, Ankum WM, et al. Uterine artery embolization in the treatment of symptomatic uterine fibroid tumors (EMMY trial): periprocedural results and complications. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2006 Mar;17(3):471–480. doi: 10.1097/01.rvi.0000203419.61593.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldberg J, Pereira L, Berghella V. Pregnancy after uterine artery embolization. Obstet Gynecol. 2002 Nov;100(5 Pt 1):869–872. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02347-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lethaby AE, Vollenhoven BJ. An evidence-based approach to hormonal therapies for premenopausal women with fibroids. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2008 Apr;22(2):307–331. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]