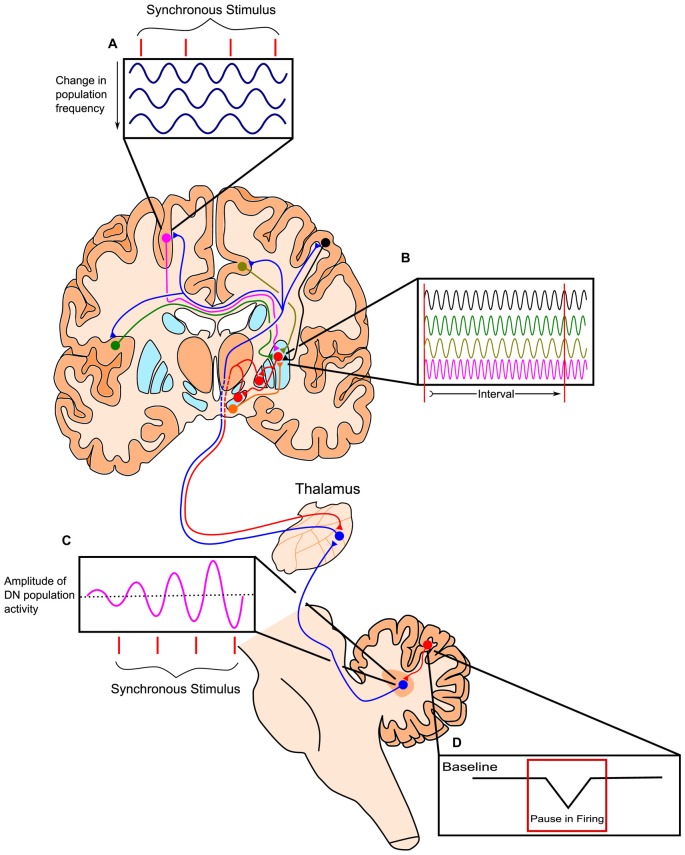

Figure 3.

Outline of the Striatal Beat-Frequency (SBF) model of interval timing with the incorporation of a cerebellar adjustment mechanism into the time code. (A) At the start of a to-be-timed signal a phasic pulse of dopamine from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) synchronizes cortical oscillations. Cortical oscillations in areas such as the prefrontal cortex (PFC) can be modulated with synchronous stimuli possibly through efferents from the thalamus. (B) These dispersed cortical neurons synapse onto medium spiny neurons (MSNs) within the striatum, which are activated at specific target durations based on the oscillatory activity pattern of synapsing projections. These neurons project from non-motor regions in the thalamus such as the caudal portion of ventralis lateralis, pars caudalis (VLcc) and receive extensive inputs from the cerebellar dentate nucleus (DN). (C) The DN also exhibits changes in population activity in response to synchronous stimuli, which may drive the modulation seen in cortical regions of the cerebrum. (D) The change in DN activity is likely modulated by decreases in tonic Purkinje cell activity (pauses) allowing for the precise tuning of timing mechanisms through disinhibition. Adapted from the initiation, continuation, adjustment, and termination (ICAT) model of temporal integration described by Lusk et al. (2016) and Petter et al. (submitted).