Figure 1.

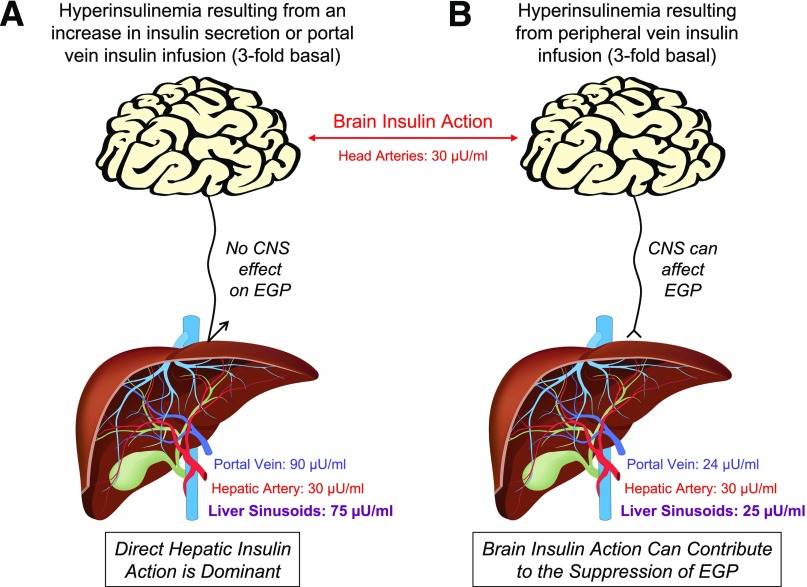

In the basal state, arterial and hepatic portal vein insulin concentrations are approximately 10 and 30 µU/mL, respectively, such that the concentration of insulin in blood entering the hepatic sinusoids is ∼25 µU/mL. A threefold increase in basal insulin secretion or portal vein insulin infusion (A) increases both arterial (brain) and liver insulin concentrations by threefold. When insulin is acutely elevated in this way, insulin’s direct hepatic effect drives the rapid suppression of EGP, and the CNS effects of insulin on the liver are masked. In response to a threefold rise in insulin brought about by infusion into a peripheral vein (B), arterial (brain) insulin concentrations are also elevated threefold, but in this case hepatic sinusoidal insulin levels remain at the basal level (∼25 μU/mL) because endogenous insulin secretion falls (exogenous insulin infusion inhibits insulin secretion in the human, dog, and rodent [12,40,41]) and the gut destroys 20% of the insulin in the blood perfusing it. Clearly, when insulin is administered intranasally, by direct infusion into the brain, or via a peripheral vein, the normal physiological insulin gradient between the brain and liver is lost. Thus, although brain insulin action can impact hepatic glucose production (albeit slowly) in the deficiency of insulin signaling at the liver, it cannot do so under circumstances in which the direct insulin signal is normal.