Abstract

Nocardioides massiliensis sp. nov strain GD13T is the type strain of N. massiliensis sp. nov., a new species within the genus Nocardioides. This strain was isolated from the faeces of a 62-year-old man admitted to intensive care for Guillain-Barré syndrome. Nocardioides massiliensis is a strictly aerobic Gram-positive rod. Herein we describe the features of this bacterium, together with the complete genome sequence and annotation. The 4 006 620 bp long genome contains 4132 protein-coding and 47 RNA genes.

Keywords: Culturomics, genome, taxonogenomics

Introduction

Nocardioides massiliensis strain GD13T (= DSM 28216 = CSUR P894) is the type strain of N. massiliensis sp. nov. This bacterium was isolated from the human faeces of a 62-year-old man admitted to intensive care for a Guillain-Barré syndrome as part of an effort called culturomics to cultivate all bacterial species from the human gut [1], [2]. The current taxonomic classification of prokaryotes is based on a combination of phenotypic and genotypic characteristics [3], [4], which includes 16S rRNA gene phylogeny, G+C content and DNA-DNA hybridization. Although these tools are considered the reference standard, they have several drawbacks [5], [6]. As a result of the declining cost of sequencing, the number of sequenced bacterial genomes has rapidly grown; to date, almost 40 000 bacterial genomes have been sequenced (GOLD Database, https://gold.jgi.doe.gov/). Hence, we recently proposed to use genomic information together with phenotypic criteria for the description of new bacterial species [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20].

Here we present a summary classification and a set of features for Nocardioides massiliensis sp. nov. strain GD13T together with the description of the complete genomic sequencing and annotation. These characteristics support the circumscription of the species Nocardioides massiliensis. The genus Nocardioides was created in 1976 (Prauser, 1976). The first two species were Nocardioides albus and Nocardioides luteus [21], [22]. These Gram-positive, aerobic and cardioform actinomycetes exhibit a high G+C content and are able to develop mycelium [21], [22]. Currently the genus Nocardioides contains 72 species, including eight described in 2013 and species from the genera Pimelobacter and Arthrobacter that were reclassified in the genus Nocardioides [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36] (LPSN, http://www.bacterio.net/). Members of the genus Nocardioides are mostly environmental bacteria found in soil or plants. To our knowledge, this is the first report of isolation of a Nocardioides species from humans.

Organism Information and Classification

A stool sample was collected from a 62-year-old man admitted to the intensive care unit of Hôpital Nord, Marseille, France, in March 2012 [2]. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Institut Fédératif de Recherche IFR48 (Faculty of Medicine, Marseille, France), under agreement 09-002. At the time of sampling, the patient had received a 10-day course of imipenem (3 g per day). The faecal specimen was preserved at −80°C after collection. Strain GD13T (Table 1) was isolated in March 2012 by cultivation on PVX agar (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Étoile, France) in an aerobic atmosphere at 28°C after 14 days of incubation. Strain GD13T exhibited a 98.07% 16S rRNA sequence identity with N. mesophilus (GenBank accession no. EF466117), the phylogenetically closest bacterial species with a validly published name (Figure 1). Its 16S rRNA sequence was deposited in European Molecular Biology Laboratory–European Bioinformatics Institute (EMBL-EBI) under number HF952922. This value was lower than the 98.7% 16S rRNA gene sequence threshold recommended by Stackebrandt and Ebers [4] to delineate a new species without carrying out DNA-DNA hybridization.

Table 1.

Classification and general features of Nocardioides massiliensis strain GD13T according to MIGS recommendations

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence codea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current classification | Domain: Bacteria | TAS [37] | |

| Phylum: Actinobacteria | TAS [38] | ||

| Class: Actinobacteria | TAS [39] | ||

| Order: Actinomycetales | TAS [39], [40], [41], [42] | ||

| Family: Nocardioidaceae | TAS [39], [42], [43], [44] | ||

| Genus: Nocardioides | TAS [21] | ||

| Species: Nocardioides massiliensis | IDA | ||

| Type strain GD13T | IDA | ||

| Gram stain | Positive | IDA | |

| Cell shape | Rod shaped | IDA | |

| Motility | Not motile | IDA | |

| Sporulation | Nonsporulating | IDA | |

| Temperature range | Mesophile | IDA | |

| Optimum temperature | 37°C | IDA | |

| MIGS-6.3 | Salinity | Unknown | IDA |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen requirement | Aerobic | IDA |

| Carbon source | Unknown | IDA | |

| Energy source | Unknown | IDA | |

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | Human gut | IDA |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | Free-living | IDA |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | Unknown | |

| Biosafety level | 2 | ||

| Isolation | Human faeces | ||

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | Marseille | IDA |

| MIGS-5 | Sample collection time | March 2012 | IDA |

| MIGS-4.1 | Latitude | 43.296482 | IDA |

| MIGS-4.1 | Longitude | 5.36978 | IDA |

| MIGS-4.3 | Depth | Surface | IDA |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | 0 m above sea level | IDA |

MIGS, minimum information about a genome sequence.

Evidence codes are as follows: IDA, inferred from direct assay; and TAS, traceable author statement (i.e. a direct report exists in the literature). These evidence codes are from the Gene Ontology project (http://www.geneontology.org/GO.evidence.shtml) [45]. If the evidence code is IDA, then the property should have been directly observed, for the purpose of this specific publication, for a live isolate by one of the authors, or by an expert or reputable institution mentioned in the acknowledgements.

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic tree highlighting position of Nocardioides massiliensis strain GD13T relative to other type strains within Nocardioides genus. Strains and their corresponding GenBank accession numbers for 16S rRNA genes are (type = T): Nocardioides massiliensis strain GD13T, HF952922; N. mesophilus strain MSL-22T, EF466117; N. iriomotensis strain IR27-S3T, AB544079; N. jensenii strain ATCC 49810T, AF005006; N. daedukensis strain MDN22T, FJ842646; N. daejeonensis strain MJ31T, JF937066; N. dubius strain KSL-104T, AY928902; N. halotolerans strain DSM 19273T, EF466122; N. daphniae strain D287T, AM398438; N. salarius strain CL-Z59T, DQ401092; N. basaltis strain J112T, EU143365; N. ginsengisegetis strain Gsoil 48T, GQ339901; N. kribbensis strain KSL-2T, AY835924; N. alkalitolerans strain DSM 16699T, AY633969; N. insulae strain DSM 17944T, DQ786794; Aeromicrobium massiliense strain JC14T, JF824798. Sequences were aligned using CLUSTALW, and phylogenetic inferences were obtained using maximum-likelihood method within MEGA6. Numbers at nodes are percentages of bootstrap values obtained by repeating analysis 500 times to generate majority consensus tree. Only bootstrap values equal to or greater than 70% are indicated. Aeromicrobium massiliense was used as outgroup. Scale bar = 1% nucleotide sequence divergence.

Phenotypic and biochemical features

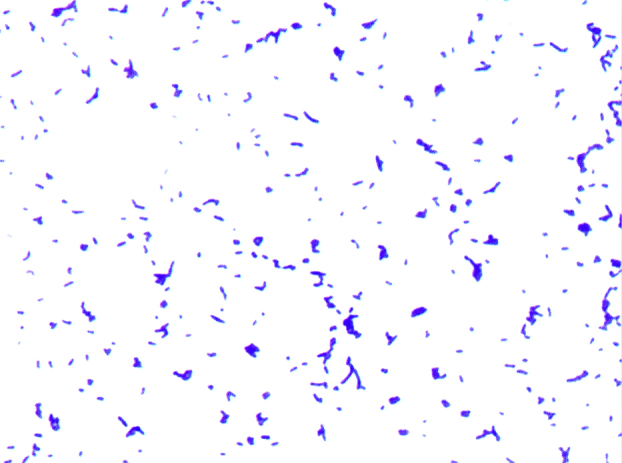

Growth was tested at different temperatures (25, 30, 37, 45, 56°C). It occurred between 25 and 37°C after 24 to 48 hours of incubation. No growth was observed at 45 or 56°C. Colonies were 0.5 mm in diameter on 5% sheep's blood–enriched Columbia agar (bioMérieux). Growth of the strain was tested under anaerobic and microaerophilic conditions using GENbag anaer and GENbag microaer systems (bioMérieux) respectively, and under aerobic conditions, with or without 5% CO2. It was achieved only aerobically. Gram staining showed Gram-positive, rod-shaped bacteria unable to form spores (Figure 2). A motility test was negative. Cells grown on agar were soft and yellowish in colour after 24 to 48 hours and could be grouped in small clumps (Figure 2). They had a mean width of 0.46 μm and a mean length of 1 μm (Figure 3).

Fig. 2.

Gram staining of Nocardioides massiliensis strain GD13T.

Fig. 3.

Transmission electron microscopy of Nocardioides massiliensis strain GD13T, using Morgani 268D (Philips, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) at operating voltage of 60 kV. Scale bar = 500 nm.

Strain GD13T exhibits catalase activity, but was negative for oxidase. Using an API ZYM strip (bioMérieux), positive reactions were observed for esterase (C4), esterase lipase (C8), acid phosphatase, alkaline phosphatase, leucine arylamidase, naphthol-AS-BI-phosphohydrolase, α-glucosidase and β-glucosidase; negative reactions were observed for β-galactosidase, α-galactosidase, valine arylamidase, cystine arylamidase, β-glucuronidase, lipase (C14), trypsin, α-chymotrypsin, N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase, α-mannosidase and α-fucosidase. Using rapid ID32A (bioMérieux), positive reactions were observed for arginine arylamidase, proline arylamidase and α-fucosidase and negative reactions were observed for arginine dihydrolase and N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase. Using rapid ID32A (bioMérieux), positive reactions were observed for arginine arylamidase, proline arylamidase and α-fucosidase; negative reactions were observed for nitrate reduction, urease, production of indole, arginine dihydrolase, N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase, serine arylamidase, histidin arylamidase, phenylalanine arylamidase and tyrosin arylamidase. Using an API 50 CH strip (bioMérieux), positive reactions were recorded for esculin hydrolysis and fermentation of d-lactose; negative reactions were obtained for fermentation of glycerol, erythritol, d-arabinose, l-arabinose, d-ribose, d-xylose, l-xylose, d-adonitol, methyl-βd-xylopyranoside, d-galactose, d-glucose, d-fructose, d-mannose, l-sorbose, l-rhamnose, dulcitol, inositol, d-mannitol, methyl-αd-xylopyranoside, methyl-αd-glucopyranoside, N-acetylglucosamine, amygdalin, arbutin, esculin ferric citrate, salicin, d-cellobiose, d-maltose, d-mellibiose, d-trehalose, inulin, d-melezitose, d-raffinose, amidon, glycogen, gentiobiose, d-turanose, d-lyxose, d-tagatose, d-fucose, l-fucose, l-arabitol, d-sorbitol, d-saccharose, xylitol, d-arabitol, potassium-5-ketogluconate and potassium 2-ketogluconate. Cells were susceptible to penicillin G, amoxicillin, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, ceftriaxone, imipenem, vancomycin, rifampicin, erythromycin, gentamicin, ciprofloxacin and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and resistant to metronidazole. Compared to N. mesophilus, its phylogenetically closest neighbor, N. massiliensis differed in α-glucosidase, β-glucosidase, esterase–lipase production and utilization of d-glucose and d-mannose (Table 2). In addition, Nocardioides species clearly differed from Aeromicrobium massiliense, a representative species from another genus within the family Nocardioidaceae.

Table 2.

Differential characteristics of Nocardioides massiliensis strain GD13T (data from this study) compared to N. dubius strain KSL-104T; N. mesophilus strain MSL-22T; N. iriomotensis strain IR27-S3T; N. daedukensis strain MDN22T, Aeromicrobium massiliense strain JC14T

| Property | N. massiliensis | N. dubius | N. mesophilus | N. iriomotensis | N. daedukensis | A. massiliense |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell diameter (μm) | 0.46 × 1 | 0.8–1.06 × 1.5–2.5 | 0.3–0.8 × 60.9–1.4 | 0.4–0.5 × 0.4–1 | 0.4–0.86 × 0 .8–3.0 | 1 × 1.7 |

| Oxygen requirement | Aerobic | Aerobic | Aerobic | Aerobic | Aerobic | Aerobic |

| Gram stain | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Motility | − | + | − | − | − | + |

| Endospore formation | − | − | − | − | + | − |

| Production of: | ||||||

| Alkaline phosphatase | + | + | + | + | − | − |

| Acid phosphatase | + | + | + | + | − | − |

| Catalase | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Oxidase | − | + | − | NA | + | − |

| Nitrate reductase | − | − | − | + | + | + |

| Urease | − | NA | − | NA | NA | − |

| α-Galactosidase | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| β-Galactosidase | − | − | − | + | − | + |

| β-Glucuronidase | − | − | − | − | − | w |

| α-Glucosidase | + | + | − | + | − | + |

| β-Glucosidase | + | + | − | + | − | + |

| Esterase | + | − | + | + | − | + |

| Esterase lipase | + | − | − | + | + | |

| Naphthol-AS-BI-phosphohydrolase | + | NA | + | + | w | − |

| N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| α-Mannosidase | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| α-Fucosidase | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Leucine arylamidase | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Valine arylamidase | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Cystine arylamidase | − | − | − | + | − | − |

| α-Chymotrypsin | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Trypsin | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| Utilization of: | ||||||

| 5-Keto-gluconate | − | NA | NA | NA | NA | + |

| d-Xylose | − | − | + | NA | − | − |

| d-Fructose | − | − | − | NA | − | − |

| d-Glucose | − | − | + | NA | − | + |

| d-Mannose | − | − | + | NA | − | − |

| Habitat | Human gut | Soil | Soil | Soil | Soil | Human gut |

+, positive result; −, negative result; w, weakly positive result; NA, data not available.

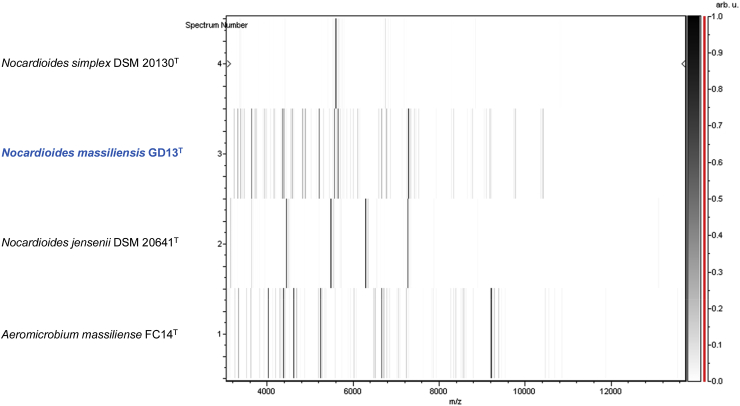

MALDI-TOF analysis

Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF) protein analysis was carried out as previously described [46]. Briefly, a pipette tip was used to pick one isolated bacterial colony from a culture agar plate and spread it as a thin film on a MSP 96 MALDI-TOF target plate (Bruker Daltonics, Leipzig, Germany). Twenty distinct deposits from 20 isolated colonies were performed for strain GD13T. Each smear was overlaid with 2 μL of matrix solution (saturated solution of alpha-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid in 50% acetonitrile, 2.5% trifluoracetic acid) and allowed to dry for 5 minutes. Measurements were performed with a Microflex spectrometer (Bruker). Spectra were recorded in the positive linear mode for the mass range of 2000 to 20 000 Da (parameter settings: ion source 1 (ISI), 20 kV; IS2, 18.5 kV; lens, 7 kV). A spectrum was obtained after 240 shots with variable laser power. The time of acquisition was between 30 seconds and 1 minute per spot. The 20 GD13T spectra were imported into MALDI BioTyper 3.0 software (Bruker) and analysed by standard pattern matching (with default parameter settings) against the main spectra of 7379 bacteria, including 48 spectra from two Nocardioides species. It corresponded to the Bruker database combined with our own database constantly incremented with new species. The method of identification included the m/z from 3000 to 15 000 Da. For every spectrum, a maximum of 100 peaks were compared with spectra in the database. The resulting score enabled the identification or not of tested species: a score of ≥2 with a validly published species enabled identification at the species level, a score of ≥1.7 but <2 enabled identification at the genus level and a score of <1.7 did not enable any identification. No significant MALDI-TOF score was obtained for strain GD13T against the Bruker database and against our own database, suggesting that our isolate was not a member of a known species. We added the spectrum from strain GD13T to our database (Figure 4). Finally, the gel view showed the spectral differences with other members of the genus Nocardioides and Aeromicrobium massiliense, a member of the genus Aeromicrobium that is closely related to the genus Nocardioides (Figure 5).

Fig. 4.

Reference mass spectrum from Nocardioides massiliensis strain GD13T. Spectra from 17 individual colonies were compared and reference spectrum was generated.

Fig. 5.

Gel view comparing Nocardioides massiliensis strain GD13T. Gel view displays raw spectra of loaded spectrum files arranged in pseudo-gel-like look. x-axis records m/z value. Left y-axis displays running spectrum number originating from subsequent spectra loading. Peak intensity is expressed in arbitrary units by greyscale scheme code, as indicated on right y-axis. Displayed species are indicated at left.

Genome Sequencing Information

Genome project history

Nocardioides massiliensis GD13T was selected for sequencing on the basis of its phenotypic differences, phylogenetic position and 16S rRNA sequence similarity to other members of the genus Nocardioides. It was part of a culturomics study aimed at isolating all bacterial species from the human digestive flora from patients treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics. It is the first sequenced genome of N. massiliensis sp. nov. The GenBank Bioproject number is PRJEB1962 and consists of 839 large contigs. Table 3 shows the project information and its association with minimum information about a genome sequence (MIGS) 2.0 compliance [47].

Table 3.

Project information

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | High-quality draft |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | Mate pair |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platform | MiSeq |

| MIGS-31.2 | Fold coverage | 86× |

| MIGS-30 | Assemblers | CLCGENOMICSWB4 |

| MIGS-32 | Gene calling method | Prodigal |

| EMBL-EBI Date of Release | 10 September 2014 | |

| NCBI project ID | PRJEB1962 | |

| EMBL-EBI accession | CCXJ00000000 | |

| MIGS-13 | Project relevance | Study of human gut microbiota |

EMBL-EBI, European Molecular Biology Laboratory–European Bioinformatics Institute; MIGS, minimum information about a genome sequence.

Growth conditions and DNA isolation

Nocardioides massiliensis strain GD13T (= DSM 28216 = CSUR P894) was cultured aerobically on 5% sheep's blood–enriched Columbia agar (bioMérieux). Bacteria grown on four petri dishes were resuspended in sterile water and centrifuged at 4°C at 2000 × g for 20 minutes. Cell pellets were resuspended in 1 mL Tris/EDTA/NaCl (10 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.0), 10 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), 300 mM NaCl) and recentrifuged under the same conditions. The pellets were then resuspended in 200 μL Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer and proteinase K and kept overnight at 37°C for cell lysis. DNA was purified with phenol/chloroform/isoamylalcohol (25:24:1), followed by an overnight precipitation with ethanol at −20°C. The DNA was resuspended in 205 μL TE buffer. DNA concentration was 401.63 ng/μL as measured by Qubit fluorometer using the high-sensitivity kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Genome sequencing and assembly

Genomic DNA (gDNA) of Nocardioides massiliensis was sequenced on a MiSeq sequencer (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) with two applications: paired end and mate pair. The paired end and the mate pair strategies were barcoded in order to be mixed respectively with 14 other genomic projects constructed according the Nextera XT library kit (Illumina) and 11 other projects with the Nextera Mate pair kit (Illumina).

The gDNA was diluted such that 1 ng of each strain's gDNA was used to construct the paired-end library. The tagmentation step fragmented and tagged the DNA. Then limited-cycle PCR amplification completed the tag adapters and introduced dual-index barcodes. After purification on Ampure beads (Life Technologies), the libraries were normalized on specific beads according to the Nextera XT protocol (Illumina). Normalized libraries are pooled into a single library for sequencing on the MiSeq. The pooled single strand library was loaded onto the reagent cartridge and then onto the instrument along with the flow cell. Automated cluster generation and paired-end sequencing with dual index reads was performed in a single 39-hour run at a 2 × 250 bp read length. Within this pooled run, the index representation was determined to be 3.93%. Total information of 3.27 Gb was obtained from a 374K/mm2 density with 94.2% (6 719 000 clusters) of the clusters passing quality control (QC) filters. From the genome sequencing process, the 248 710 produced Illumina paired end reads for Nocardioides massiliensis were filtered according to the read qualities.

The mate pair library was constructed from 1 μg of gDNA using the Nextera Mate Pair Illumina guide. The gDNA sample was simultaneously fragmented and tagged with a mate pair junction adapter. The profile of the fragmentation was validated on an Agilent 2100 BioAnalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with a DNA7500 lab chip. The DNA fragments ranged in size from 1 to 8.4 kb with a mean size of 3.7 kb. No size selection was performed, and 240 ng tagmented fragments were circularized. The larger circularized DNA molecules were physically sheared to smaller sized fragments with a mean size of 839 bp on the Covaris device S2 in microtubes (Woburn, MA, USA). The library's profile and the quantitation were visualized on a High Sensitivity Bioanalyzer LabChip. The libraries were normalized to 2 nM and pooled. After a denaturation step and dilution at 10 pM, the pool of libraries was loaded onto the reagent cartridge and then onto the instrument along with the flow cell. Automated cluster generation and sequencing run was performed in a single 39-hour run at a 2 × 250 bp read length. Total mate paired run information of 3.2 Gb was obtained from a 690K/mm2 density with 95.4% (13 264 000 clusters) of the clusters passing QC filters. Within this pooled run, the index representation for Nocardioides massiliensis was determined to be 8.12%. From this genome sequencing process, the 1 027 586 produced Illumina paired end reads of N. massiliensis were filtered according to the read qualities. The reads obtained from both applications were trimmed and the optimal assembly was obtained through the CLC genomics wb4 software with 839 contigs which generated a genome size of 4.00 Mb.

Genome annotation and comparison

Open reading frames (ORFs) were predicted using Prodigal [48] with default parameters, but the predicted ORFs were excluded if they spanned a sequencing gap region. The predicted bacterial protein sequences were searched against the GenBank database [49] and the Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COGs) database using BLASTP. The tRNAScanSE tool [50] was used to find tRNA genes, whereas ribosomal RNAs were found by using RNAmmer [51] and BLASTN against the GenBank database. Lipoprotein signal peptides and the number of transmembrane helices were predicted using SignalP [52] and TMHMM [53] respectively. ORFans were identified if their BLASTP E value was lower than 1e-03 for alignment length greater than 80 amino acids. If alignment lengths were smaller than 80 amino acids, we used an E value of 1e-05. Such parameter thresholds have already been used in previous works to define ORFans.

For the genomic comparison, we compared the genome sequence of N. massiliensis strain GD13T (GenBank accession no. CCXJ00000000) with those of Nocardioides alkalitolerans strain DSM 16699 (GenBank accession no. AUFN00000000), Nocardioides halotolerans strain DSM 19273 (AUGT00000000), Nocardioides insulae strain DSM 17944 (AUGU00000000) and Aeromicrobium massiliense strain JC14T (CAHG00000000). To estimate the nucleotide sequence similarity at the genome level between N. massiliensis and other members of the family Nocardioidaceae, we determined the average genomic identity of orthologous gene sequences (AGIOS) parameter using the MAGi (Marseille Average genomic identity) software as follows: orthologous proteins were detected using the Proteinortho software (version 1.4) [54] using the following parameters: E value 1e-5, 30% percentage of identity, 50% coverage and algebraic connectivity of 50%; after fetching the corresponding nucleotide sequences of orthologous proteins for each pair of genomes, we determined the mean percentage of nucleotide sequence identity using the Needleman-Wunsch global alignment algorithm; Artemis [55] was used for data management, and DNAPlotter [56] was used for visualization of genomic features. The Mauve alignment tool was used for multiple genomic sequence alignment and visualization [57].

Genome properties

The genome of N. massiliensis strain GD13T is 4 006 620 bp long with a 71.0% G+C content (Table 4, Figure 6). Of the 4179 predicted genes, 4132 were protein-coding genes and 47 were RNAs. Three rRNA genes (one 16S rRNA, one 23S rRNA and one 5S rRNA) and 44 predicted tRNA genes were identified in the genome. A total of 2783 genes (66.59%) were assigned a putative function, and 382 genes (9.24%) were identified as ORFans. The remaining genes were annotated as hypothetical proteins. The properties and the statistics of the genome are summarized in Table 4. The distribution of genes into COGs functional categories is presented in Table 5.

Table 4.

Nucleotide content and gene count levels the genome

| Attribute | Value | % of totala |

|---|---|---|

| Size (bp) | 4 006 620 | 100 |

| G+C content (bp) | 2 844 700 | 71.0 |

| Coding region (bp) | 3 668 187 | 91.55 |

| Total genes | 4179 | 100 |

| RNA genes | 47 | 1.12 |

| Protein-coding genes | 4132 | 98.87 |

| Genes with function prediction | 2408 | 57.62 |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 2783 | 66.59 |

| Genes with peptide signals | 262 | 6.26 |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 899 | 21.51 |

COGS, Clusters of Orthologous Groups database.

Total is based on either size of genome in base pairs or total number of protein-coding genes in annotated genome.

Fig. 6.

Graphical circular map of chromosome of Nocardioides massiliensis strain GD13T. From outside in, outer two circles show ORFs oriented in forward (coloured by COGs categories) and reverse (coloured by COGs categories) direction respectively. Third circle marks rRNA gene operon (red) and tRNA genes (green). Fourth circle shows G+C% content plot. Innermost circle shows GC skew, with purple indicating negative values and olive positive values.

Table 5.

Number of genes associated with 25 general COGs functional categories

| Code | Value | % | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 166 | 4.01 | Translation |

| A | 1 | 0.02 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 240 | 5.80 | Transcription |

| L | 214 | 5.17 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 1 | 0.02 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 28 | 0.67 | Cell cycle control, mitosis and meiosis |

| Y | 0 | 0 | Nuclear structure |

| V | 49 | 1.18 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 112 | 2.71 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 130 | 3.14 | Cell wall/membrane biogenesis |

| N | 28 | 0.67 | Cell motility |

| Z | 0 | 0 | Cytoskeleton |

| W | 0 | 0 | Extracellular structures |

| U | 43 | 1.04 | Intracellular trafficking and secretion |

| O | 95 | 2.29 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 229 | 5.54 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 159 | 3.84 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 315 | 7.62 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 73 | 1.76 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 126 | 3.04 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 268 | 6.48 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 213 | 5.15 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 178 | 4.30 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 460 | 11.13 | General function prediction only |

| S | 190 | 4.59 | Function unknown |

| — | 1396 | 33.4 | Not in COGs |

COGS, Clusters of Orthologous Groups database.

Extended insights from the genome sequence

The draft genome of N. massiliensis has a larger size than that of A. massiliense (4.00 and 3.32 Mb respectively) but smaller than N. alkalitolerans, N. halotolerans and N. insulae (4.85, 4.86 and 4.06 Mb respectively). The G+C content of N. massiliensis is higher than those of N. insulae (71.0 and 70.8% respectively) but less than that of A. massiliense, N. alkalitolerans and N. halotolerans (72.6, 73.1 and 72% respectively). The gene content of N. massiliensis is larger than those of A. massiliense and N. insulae (4179, 3328 and 3702 respectively) and smaller than those of N. alkalitolerans and N. halotolerans (4634 and 4633 respectively). However, the distribution of genes into COGs categories was similar in all compared genomes (Figure 7). In addition, N. massiliensis shared 1447, 1745, 1693 and 1598 orthologous genes with A. massiliense, N. alkalitolerans, N. halotolerans and N. insulae. Among Nocardioides species, AGIOS values ranged from 75.67% between N. alkalitolerans and N. insulae to 77.56% between N. alkalitolerans and N. halotolerans. When considering N. massiliensis, AGIOS values were 75.06, 76.67 and 76.82 with N. insulae, N. alkalitolerans and N. halotolerans respectively, in the same range as among other Nocardioides species (Table 6).

Fig. 7.

Distribution of functional classes of predicted genes on chromosomes of Nocardioides massiliensis (NM), Aeromicrobium massiliense (AE), Nocardioides alkalitolerans (NA), Nocardioides halotolerans (NH) and Nocardioides insulae (NI) according to COGs category. For each genome, percentage of each gene category is indicated.

Table 6.

Pairwise comparison of Nocardioides massiliensis strain GD13T with other species showing (upper right) numbers of orthologous proteins shared between compared genomes and (lower left) AGIOS values

| Nocardioides massiliensis | Aeromicrobium massiliense | Nocardioides alkalitolerans | Nocardioides halotolerans | Nocardioides insulae | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N. massiliensis | 4132a | 1447 | 1745 | 1693 | 1598 |

| A. massiliense | 75.17 | 2297a | 1605 | 1501 | 1517 |

| N. alkalitolerans | 76.67 | 75.61 | 4585a | 1872 | 1822 |

| N. halotolerans | 76.82 | 75.14 | 77.56 | 4677a | 1753 |

| N. insulae | 75.06 | 74.12 | 75.67 | 76.73 | 3648a |

AGIOS, average genomic identity of orthologous gene sequences.

Numbers of proteins per genome.

Conclusion

On the basis of phenotypic, phylogenetic and genomic analyses, we formally propose the creation of Nocardioides massiliensis sp. nov. The strain was isolated from a stool sample from a 62-year-old man admitted to intensive care in Marseille, France, for Guillain-Barré syndrome and who had received 10 days of broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Description of Nocardioides massiliensis strain GD13T sp. nov

Nocardioides massiliensis (mas.si.li.en'sis, L. masc. adj., from massiliensis of Massilia, the ancient Roman name for Marseille, France, where the type strain was isolated).

Cells are Gram-positive, nonsporulating, nonmotile and rod-shaped bacilli with a mean diameter and length of 0.46 and 1.0 μm respectively. Colonies are 0.5 mm in diameter and are smooth and pale yellow on 5% sheep's blood–enriched Columbia agar (bioMérieux). Growth occurred aerobically between 25 and 37°C.

Cells exhibit catalase activity but are oxidase negative. Positive reactions are observed for esterase (C4), esterase lipase (C8), acid phosphatase, alkaline phosphatase, leucine arylamidase, naphthol-AS-BI-phosphohydrolase, α-glucosidase, β-glucosidase, arginine arylamidase, proline arylamidase, esculin hydrolysis and fermentation of d-lactose. Negative reactions are observed for β-galactosidase, α-galactosidase, valine arylamidase, cystine arylamidase, β-glucuronidase, lipase (C14), trypsin, α-chymotrypsin, N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase, α-mannosidase, α-fucosidase, arginine dihydrolase, N acetyl-β-glucosaminidase, nitrate reductase, urease, indole production, arginine dihydrolase, N acetyl-β-glucosaminidase, serine arylamidase, histidin arylamidase, phenylalanine arylamidase, tyrosin arylamidase, fermentation of glycerol, erythritol, d-arabinose, l-arabinose, d-ribose, d-xylose, l-xylose, d-adonitol, methyl-βd-xylopyranoside, d-galactose, d-glucose, d-fructose, d-mannose, l-sorbose, l-rhamnose, dulcitol, inositol, d-mannitol, methyl-αd-xylopyranoside, methyl-αd-glucopyranoside, N-acetylglucosamine, amygdalin, arbutin, esculin ferric citrate, salicin, d-cellobiose, d-maltose, d-mellibiose, d-trehalose, inulin, d-melezitose, d-raffinose, amidon, glycogen, gentiobiose, d-turanose, d-lyxose, d-tagatose, d-fucose, l-fucose, l-arabitol, d-sorbitol, d-saccharose, xylitol, d-arabitol, potassium-5-ketogluconate and potassium 2-ketogluconate. Cells are susceptible to penicillin G, amoxicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, ceftriaxone, imipenem, vancomycin, rifampicin, erythromycin, gentamicin, ciprofloxacin and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and resistant to metronidazole.

The G+C content of the genome is 71.0%. The 16S rRNA and whole-genome sequence of N. massiliensis strain GD13T are deposited in EMBL-EBI under the accession numbers HF952922 and CCXJ00000000 respectively. The type strain GD13T (= CSUR P894 = DSM 28216) was isolated from the faecal flora of a 62-year-old man admitted to intensive care in Marseille, France, for Guillain-Barré syndrome who had received 10 days of broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Xegen Company (http://www.xegen.fr/) for automating the genomic annotation process. They also thank K. Griffiths for English-language review and C. Andrieu for administrative assistance. This study was funded by the Fondation Méditerranée Infection.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Lagier J.C., Armougom F., Million M., Hugon P., Pagnier I., Robert C. Microbial culturomics: paradigm shift in the human gut microbiome study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:1185–1193. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dubourg G., Lagier J.C., Armougom F., Robert C., Hamad I., Brouqui P. Culturomics and pyrosequencing evidence of the reduction in gut microbiota diversity in patients with broad-spectrum antibiotics. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2014;4:117–124. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2014.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tindall B.J., Rosselló-Móra R., Busse H.J., Ludwig W., Kämpfer P. Notes on the characterization of prokaryote strains for taxonomic purposes. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2010;60:249–266. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.016949-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stackebrandt E., Ebers J. Taxonomic parameters revisited: tarnished gold standards. Microbiol Today. 2006;33:152–155. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stackebrandt E., Frederiksen W., Garrity G.M., Grimont P.A., Kämpfer P., Maiden M.C. Report of the ad hoc committee for the re-evaluation of the species definition in bacteriology. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2002;52(Pt 3):1043–1047. doi: 10.1099/00207713-52-3-1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosselló-Móra R. DNA-DNA reassociation methods applied to microbial taxonomy and their critical evaluation. In: Stackebrandt E., editor. Molecular identification, systematics, and population structure of Prokaryotes. Springer; Berlin: 2006. pp. 23–50. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramasamy D., Mishra A.K., Lagier J.C., Padhmanabhan R., Rossi M., Sentausa E. A polyphasic strategy incorporating genomic data for the taxonomic description of novel bacterial species. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2014;64:384–391. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.057091-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fournier P.E., Lagier J.C., Dubourg G., Raoult D. From culturomics to taxonomogenomics: a need to change the taxonomy of prokaryotes in clinical microbiology. Anaerobe. 2015;36:73–78. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2015.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lagier J.C., El Karkouri K., Nguyen T.T., Armougom F., Raoult D., Fournier P.E. Non-contiguous finished genome sequence and description of Anaerococcus senegalensis sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci. 2012;6:116–125. doi: 10.4056/sigs.2415480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lagier J.C., Armougom F., Mishra A.K., Nguyen T.T., Raoult D., Fournier P.E. Non-contiguous finished genome sequence and description of Alistipes timonensis sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci. 2012;6:315–324. doi: 10.4056/sigs.2685971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mishra A.K., Lagier J.C., Robert C., Raoult D., Fournier P.E. Non-contiguous finished genome sequence and description of Clostridium senegalense sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci. 2012;6:386–395. doi: 10.4056/sigs.2766062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mishra A.K., Lagier J.C., Robert C., Raoult D., Fournier P.E. Non contiguous-finished genome sequence and description of Peptoniphilus timonensis sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci. 2012;7:1–11. doi: 10.4056/sigs.2956294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mishra A.K., Lagier J.C., Rivet R., Raoult D., Fournier P.E. Non-contiguous finished genome sequence and description of Paenibacillus senegalensis sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci. 2012;7:70–81. doi: 10.4056/sigs.3056450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lagier J.C., Gimenez G., Robert C., Raoult D., Fournier P.E. Non-contiguous finished genome sequence and description of Herbaspirillum massiliense sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci. 2012;7:200–209. doi: 10.4056/sigs.3086474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roux V., El Karkouri K., Lagier J.C., Robert C., Raoult D. Non-contiguous finished genome sequence and description of Kurthia massiliensis sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci. 2012;7:221–232. doi: 10.4056/sigs.3206554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kokcha S., Ramasamy D., Lagier J.C., Robert C., Raoult D., Fournier P.E. Non-contiguous finished genome sequence and description of Brevibacterium senegalense sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci. 2012;7:233–245. doi: 10.4056/sigs.3256677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramasamy D., Kokcha S., Lagier J.C., Nguyen T.T., Raoult D., Fournier P.E. Genome sequence and description of Aeromicrobium massiliense sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci. 2012;7:246–257. doi: 10.4056/sigs.3306717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lagier J.C., Ramasamy D., Rivet R., Raoult D., Fournier P.E. Non contiguous-finished genome sequence and description of Cellulomonas massiliensis sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci. 2012;7:258–270. doi: 10.4056/sigs.3316719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lagier J.C., Elkarkouri K., Rivet R., Couderc C., Raoult D., Fournier P.E. Non contiguous-finished genome sequence and description of Senegalemassilia anaerobia gen. nov., sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci. 2013;7:343–356. doi: 10.4056/sigs.3246665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lagier J.C., El Karkouri K., Mishra A.K., Robert C., Raoult D., Fournier P.E. Non contiguous-finished genome sequence and description of Enterobacter massiliensis sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci. 2013;7:399–412. doi: 10.4056/sigs.3396830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prauser H. Nocardioides, a new genus of the order Actinomycetales. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1976;26:58–65. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prauser H. Nocardioides luteus spec. nov. Zeitschr Allgem Microbiol. 1984;24:647–648. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alias-Villegas C., Jurado V., Laiz L., Miller A.Z., Saiz-Jimenez C. Nocardioides albertanoniae sp. nov., isolated from Roman catacombs. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 2013;63:1280–1284. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.043885-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cho Y., Jang G.I., Hwang C.Y., Kim E.H., Cho B.C. Nocardioides salsibiostraticola sp. nov., isolated from biofilm formed in coastal seawater. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 2013;63:3800–3806. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.051037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cho Y., Jang G.I., Cho B.C. Nocardioides marinquilinus sp. nov., isolated from coastal seawater. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 2013;63:2594–2599. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.047902-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Du H.J., Wei Y.Z., Su J., Liu H.Y., Ma B.P., Guo B.L.Y. Nocardioides perillae sp. nov., isolated from surface-sterilized roots of Perilla frutescens. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 2013;63:1068–1072. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.044982-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han J.H., Kim T.S., Joung Y., Kim M.N., Shin K.S., Bae T. Nocardioides endophyticus sp. nov. and Nocardioides conyzicola sp. nov., isolated from herbaceous plant roots. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 2013;63:4730–4734. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.054619-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim J.K., Liu Q.M., Park H.Y., Kang M.S., Kim S.C., Im W.T. Nocardioides panaciterrulae sp. nov., isolated from soil of a ginseng field, with ginsenoside converting activity. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 2013;103:1385–1393. doi: 10.1007/s10482-013-9919-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu Q., Xin Y.H., Liu H.C., Zhou Y.G., Wen Y. Nocardioides szechwanensis sp. nov. and Nocardioides psychrotolerans sp. nov., isolated from a glacier. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 2013;63:129–133. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.038091-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cui Y., Woo S.G., Lee J., Sinha S., Kang M.S., Jin L. Nocardioides daeguensis sp. nov., a nitrate-reducing bacterium isolated from activated sludge of an industrial wastewater treatment plant. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 2013;63:3727–3732. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.047043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Collins M.D., Dorsch M., Stackebrandt E. Transfer of Pimelobacter tumescens to Terrabacter gen. nov. as Terrabacter tumescens comb. nov. and of Pimelobacter jensenii to Nocardioides as Nocardioides jensenii comb. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1989;39:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fan X., Qiao Y., Gao X., Zhang X.H. Nocardioides pacificus sp. nov., isolated from deep sub-seafloor sediment of South Pacific Gyre. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 2014;64:2217–2222. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.059873-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Glaeser S.P., McInroy J.A., Busse H.J., Kämpfer P. Nocardioides zeae sp. nov., isolated from the stem of Zea mays. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 2014;64:2491–2496. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.061481-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee S.D., Seong C.N. Nocardioides opuntiae sp. nov., isolated from a soil of cactus. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 2014;(4):2094–2099. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.060400-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang D.F., Zhong J.M., Zhang X.M., Jiang Z., Zhou E.M., Tian X.P. Nocardioides nanhaiensis sp. nov., an actinobacterium isolated from a marine sediment sample. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 2014;64(pt 8):2718–2722. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.062851-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee S.D., Lee D.W. Nocardioides rubroscoriae sp. nov., isolated from volcanic ash. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 2014;105:1017–1023. doi: 10.1007/s10482-014-0161-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Woese C.R., Kandler O., Wheelis M.L. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:4576–4579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garrity G.M., Holt J.G. The road map to the manual. In: Garrity G.M., Boone D.R., Castenholz R.W., editors. Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology. 2nd ed. vol. 1. Springer; New York: 2001. pp. 119–169. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stackebrandt E., Ebers J., Rainey F., Ward-Rainey N. Proposal for a new hierarchic classification system, Actinobacteria classis nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:479–491. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Skerman V., McGowan V., Sneath P. Approved lists of bacterial names. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1980;30:225–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buchanan R.E. Studies in the nomenclature and classification of bacteria. II. The primary subdivisions of the Schizomycetes. J Bacteriol. 1917;2:155–164. doi: 10.1128/jb.2.2.155-164.1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhi X.Y., Li W.J., Stackebrandt E. An update of the structure and 16S rRNA gene sequence–based definition of higher ranks of the class Actinobacteria, with the proposal of two new suborders and four new families and emended descriptions of the existing higher taxa. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2009;59:589–608. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.65780-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nesterenko O.A., Kvasnikov E.I., Nogina T.M. Nocardioidaceae fam. nov., a new family of the order Actinomycetales Buchanan 1917. Mikrobiol Zh. 1985;47:3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Validation list no. 34. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1990;40:320–321. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ashburner M., Ball C.A., Blake J.A., Botstein D., Butler H., Cherry J.M. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Seng P., Drancourt M., Gouriet F., La Scola B., Fournier P.E., Rolain J.M. Ongoing revolution in bacteriology: routine identification of bacteria by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:543–551. doi: 10.1086/600885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Field D., Garrity G., Gray T., Morrison N., Selengut J., Sterk P. The minimum information about a genome sequence (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:541–547. doi: 10.1038/nbt1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hyatt D., Chen G.L., Locascio P.F., Land M.L., Larimer F.W., Hauser L.J. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:119. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Benson D.A., Karsch-Mizrachi I., Clark K., Lipman D.J., Ostell J., Sayers E.W. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D48–D53. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lowe T.M., Eddy S.R. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:955–964. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lagesen K., Hallin P., Rodland E.A., Staerfeldt H.H., Rognes T., Ussery D.W. RNAmmer: consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:3100–3108. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bendtsen J.D., Nielsen H., von Heijne G., Brunak S. Improved prediction of signal peptides: SignalP 3.0. J Mol Biol. 2004;340:783–795. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Krogh A., Larsson B., von Heijne G., Sonnhammer E.L. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol. 2001;305:567–580. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lechner M., Findeib S., Steiner L., Marz M., Stadler P.F., Prohaska S.J. Proteinortho: detection of (co-)orthologs in large-scale analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:124. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rutherford K., Parkhill J., Crook J., Horsnell T., Rice P., Rajandream M.A. Artemis: sequence visualization and annotation. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:944–945. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.10.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Carver T., Thomson N., Bleasby A., Berriman M., Parkhill J. DNAPlotter: circular and linear interactive genome visualization. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:119–120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Darling A.C., Mau B., Blattner F.R., Perna N.T. Mauve: multiple alignment of conserved genomic sequence with rearrangements. Genome Res. 2004;14:1394–1403. doi: 10.1101/gr.2289704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]