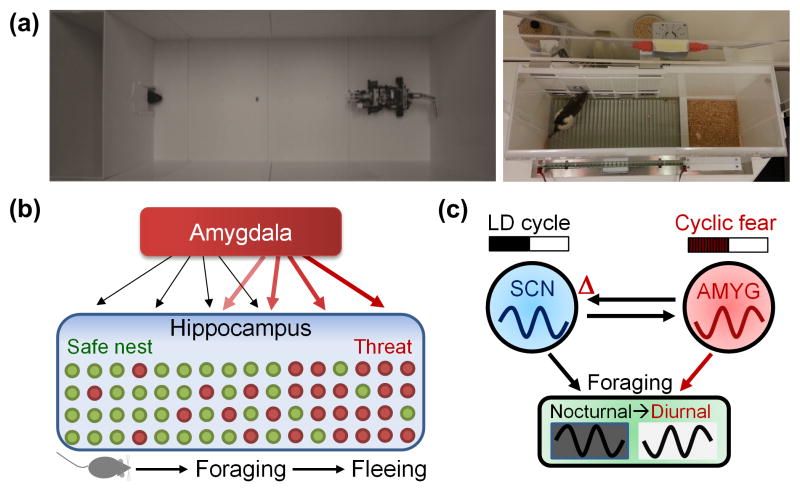

Figure 5. Fear influences foraging distance and time.

(A) Ecologically-relevant ‘approach food-avoid predator’ (left) and ‘closed economy’ (right) paradigms. (B) In the approach-avoid paradigm, a hunger-motivated rat seeks food pellets placed at varying distances from the nest. As the animal nears the food, the predatory robot executes a programmed set of threatening actions, i.e., surges forward a fixed distance and snaps its ‘jaws’ before returning to its starting position. In response, rats instinctively flee into the safety of the nest and freeze inside. This is followed by the rat’s display of a stretched posture anchored inside the nest opening as it scans the outside area (risk-assessment), and then cautiously venturing out, pausing, and moving toward the food until the robot’s surge retriggers the rat’s fear responses. While all rats were unable to procure the pellet placed distal to the nest, most were able to acquire the pellet placed near the nest, suggesting that rats form a distance gradient of fear near the robot [55]. In parallel, hippocampal place cells exhibited remapping of place fields and increased theta rhythm as the animals advanced toward the vicinity of the robot but not inside/near the nest regions [56]. These behavioral and neurophysiological effects were abolished by amygdalar lesions/inactivation. (C) In the closed economy paradigm, fear, avoidance, and appetitive behaviors are integrated within the rat’s living situation. It consists of a safe nest and foraging zone that has to be entered to press levers for food and can be rendered dangerous by footshocks. When footshocks were pseudo-randomly presented only during the dark phase of the 12 h/12 h light:dark (LD) cycle, rats switched their natural foraging behavior from the dark to the light phase, and this switch was maintained as a free-running circadian rhythm upon removal of light cues and footshocks. This fear-entrained circadian behavior was dependent on an intact amygdala (AMYG) and suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) [80].