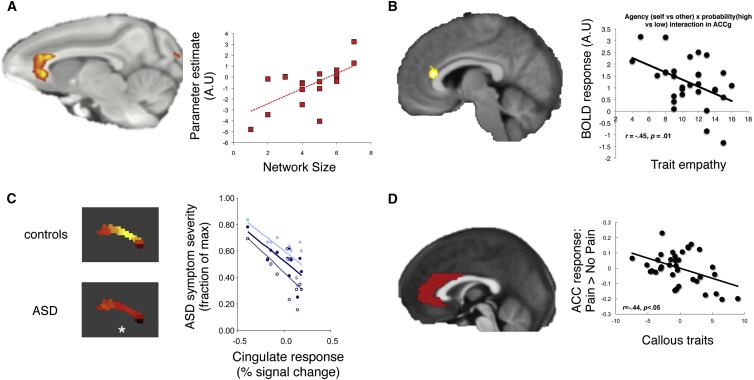

Figure 4.

Variability and Pathology in ACCg Activity to Other-Oriented Information

(A) Resting-state activity in the macaque ACCg (left) correlates with social network size (right; x axis: size of social group, y axis: strength of resting-state connectivity between ACCg and TPJ/STS) (Sallet et al., 2011).

(B) The extent to which the ACCg (left) exclusively processes the expected value of others’ reward correlates with self-reported levels of emotion contagion (a component of empathy). The graph to the right shows the extent to which the ACCg signaled an interaction between probability of reward and agent identity (self versus other). In this graph, the interaction term (BOLD response) correlated with emotion contagion (trait empathy, x axis). Higher levels of empathy were related to greater specialization of the ACCg for processing others’ reward and not subjects’ own reward (Lockwood et al., 2015).

(C) Differences in ACC activity between healthy controls and a high-functioning ASD group during a social interaction task (Chiu et al., 2008). Patterns of activity in controls and ASD (left) were different at a moment in time when subjects could predict the consequences of their actions on the reward that would be obtained by another. The response of the cingulate at that moment in time, correlated with ASD symptom severity (right).

(D) Activity in the ACC to the pain of others (pictures of others’ in pain: y axis) is negatively correlated with callous (psychopathic/ICU-callous traits) traits (x axis) in children with conduct problems (Lockwood et al., 2013). Although responses in (C) and (D) were not localized specifically to the sulcus or gyrus, they do provide evidence that links together ACC and impairments in social behavior.