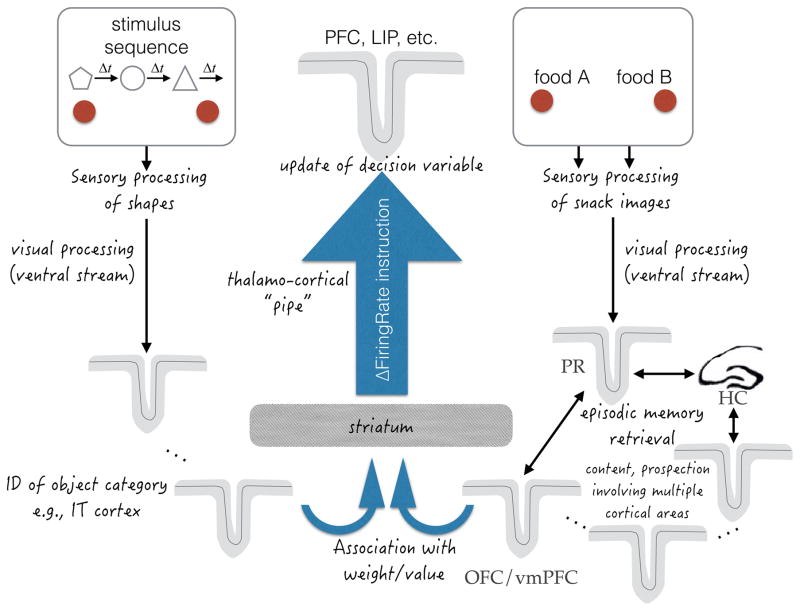

Figure 4. Putative neural mechanisms involved in updating a decision variable using memory.

The symbols task (left) and, per our hypothesis, the snacks task (right) use memory to update a decision variable. The diagram is intended to explain why the updating of a decision variable is likely to be sequential in general, when evidence is derived from memory. In both tasks, visual information is processed to identify the shapes and snack items. This information must lead to an update of a decision variable represented by neurons in associative cortex with the capacity to represent cumulative evidence. This includes area LIP when the choice is communicated by an eye movement, but there are many areas of association cortex that are likely to represent the evolving decision variable. The update of the decision variable is effectively an instruction to increment or decrement the firing rate of neurons that represent the choice targets (provisional plans to select one or the other) by an amount, ΔFiringRate. The ΔFiringRate instruction is informed by a memory retrieval process, which is likely to involve the striatum. In the symbols task this is an association between the shape that is currently displayed and a learned weight (logLR value; Fig. 2C). In the snacks task it is likely to involve episodic memory, which leads to a value association represented in the vmPFC/OFC. Notice that there are many possible sources of evidence in the symbols task and potentially many more in the snacks task. Yet there is limited access to the sites of the decision variable (thalamo-cortical “pipe”). Thus, access to this pipe is likely to be sequential, even when the evidence is not supplied as a sequence. Anatomical labels and arrows should be viewed as hypothetical and not necessarily direct. PR, perirhinal cortex; HC, hippocampus.