Abstract

Ethrel is the most effective stimuli in prolonging the latex flow that consequently increases yield per tapping. This effect is largely ascribed to the enhanced lutoid stability, which is associated with the decreased release of initiators of rubber particle (RP) aggregation from lutoid bursting. However, the increase in both the bursting index of lutoids and the duration of latex flow after applying ethrel or ethylene gas in high concentrations suggests that a new mechanism needs to be introduced. In this study, a latex allergen Hev b 7-like protein in C-serum was identified by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI TOF MS). In vitro analysis showed that the protein acted as a universal antagonist of RP aggregating factors from lutoids and C-serum. Ethrel treatment obviously weakened the effect of C-serum on RP aggregation, which was closely associated with the increase in the level of the Hev b 7-like protein and the decrease in the level of the 37 kDa protein, as revealed by sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), western blotting analysis and antibody neutralization. Thus, the increase of the Hev b 7-like protein level or the ratio of the Hev b 7-like protein to the 37 kDa protein in C-serum should be primarily ascribed to the ethrel-stimulated prolongation of latex flow duration.

Keywords: duration of latex flow, ethrel, Hev b 7, Hevea brasiliensis Muell. Arg, rubber particle aggregation

Rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis Muell. Arg.) is the only cultivated plant to meet most of the demand for commercial natural rubber in the world (1). Laticifers in the secondary phloem are anastomosed as a result of the partial hydrolysis of adjacent walls, and thus, a tube-like network is formed throughout the plant (2–4). When laticifers are wounded by tapping (i.e. cutting the trunk bark in 2-day intervals for the general purpose of latex collection), their collective latex or cytoplasm flows from the wound site until the severed laticifers are plugged (5). Although the formation of plugs at the end of the severed laticifers is vital to preventing the loss of the rubber tree’s metabolites and entry of pathogens into the phloem, it is also a limiting factor for the yield of Hevea (6, 7). Accordingly, numerous works have been commissioned to understand the mechanism of plug formation. One hypothesis is that lutoid, a type of single-membrane microvacuole with lysosomal characteristics (2), plays a pivotal role in triggering the formation of plugs (7–10).

Under an electron microscope, latex coagulation occurs around the fractured lutoids in the plug materials (8). The release of the lutoid membrane debris, together with Ca2+ into the latex cytosolic phase, has been implicated as the initiator of latex coagulation, or the formation of the rubber coagulum (9, 11). In vitro analysis shows that proteins in the lutoid, such as hevein, β-1,3-glucanase and the combination of chitinase and β-1,3-glucanase, behave as initiators of rubber particle (RP) aggregation (10, 12). In addition, Hevea latex lectin (HLL) on the lutoid membrane has a strong ability to aggregate the RPs (7). Thus, the initiators of latex coagulation are primarily sequestered in lutoids.

In natural rubber production, ethrel has been widely used to prolong the duration of latex flow since its introduction in 1970s (13). Because materials released from the fractured lutoids are quite effective at initiating latex coagulation, which is believed to result in the plugging of the severed laticifer end (7), the effect of ethrel on latex flow prolongation has long been ascribed to enhanced lutoid stability. However, the application of ethrel or ethylene gas in high concentrations results in a significant increase in both the bursting index of lutoids, the duration of latex flow and the level of active oxygen (14, 15). In summary, under this condition, lutoids are less stable and the duration of latex flow is remarkably prolonged. In addition, ethrel and tapping up-regulate the expression of the gene encoding hevein (16), the initiator of latex coagulation (10, 12). Therefore, the prolongation of latex flow in ethrel-stimulated rubber trees may not be related to the enhanced lutoid stability. Alternatively, the inhibition of RP aggregation by increasing the inhibitors rather than decreasing the initiators should be considered. In this study, a latex allergen Hev b 7-like protein in C-serum is characterized as a universal antagonist of RP aggregating factors, such as B-serum (inclusions from fractured lutoids), lutoid debris and hevein, as well as a glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH)-like protein in C-serum, and an alternative cue for the ethrel-stimulated prolongation of latex flow duration is suggested.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

Sephacryl S-200HR and DEAE-Sepharose were purchased from GE (USA). The BCIP/NBT kit and protein marker were obtained from TIANGEN Biotech Co., Ltd. (China). The goat-anti–rabbit secondary antibodies labelled with alkaline phosphatase were from PIERCE (Rockford, IL). The polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane was from Bio-Rad. All other chemicals were of analytical reagent grade.

Plant materials and treatments

Eight-year-old virgin trees and regularly tapped trees of the rubber tree clone CATAS7-33-97 were grown in the Experimental Farm of the Chinese Academy of Tropical Agricultural Sciences of China on Hainan Island. Ten of the virgin trees and five of the regularly tapped trees were selected in this study. Five of the selected virgin trees were treated with 2% ethrel, and as a control, the other virgin trees were treated with water. Latex was separately collected from each of the five virgin trees 48 h after treatments, and the duration of latex flow was observed. Fresh latex from the selected trees was collected in an ice-chilled tube. The latex was fractionated into the floating rubber fraction, C-serum (latex cytosol) and the bottom (lutoid) fraction by centrifugation at 22,000 revolutions per minute (rpm) for 1 h at 4°C. Only the C-serum of latex from the virgin trees was collected and used to perform the analysis of RP aggregation as well as analysis of proteins by sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) and western-blot. The latex from the regularly tapped trees was collected and centrifuged at 22,000 rpm for 1 h at 4°C. The fractions of floating rubber and C-serum were used to isolate small RPs and concentrate the proteins by ammonium sulphate precipitation, respectively. After being washed three times with washing buffer containing 0.1 M Tris-HCl and 0.4 M mannitol (pH 7.2), the bottom fraction (lutoids) was used to prepare B-serum by treatment with freeze-thaw cycles.

Purification of 37 and 44 kDa proteins

Proteins in the C-serum collected from the regularly tapped trees were fractionated with 50–70% and 70–85% (NH4)2SO4 saturation in turn. The protein pellets were recovered by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 20 min and dialysed against 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4). The crude proteins were concentrated by ultra-filtration and purified by size-based column chromatography and ion exchange column chromatography as described by Wititsuwannakul et al. (17). Sephacryl S-200HR and DEAE-sepharose were used as media for size-based column chromatography and ion exchange column chromatography, respectively. The size-based column was eluted with 0.05 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), and the ion exchange column was eluted by the linear gradient increase of 0–0.5 M NaCl.

Protein quantification

The purified proteins, as well as those in C-serum, B-serum and immune serum, were quantified according to the method of Bradford (18) using bovine serum albumin as standard.

SDS–PAGE and western blotting

SDS–PAGE was performed using 12% SDS–polyacrylamide separating gels, 25 mM Tris base, 192 mM glycine and 0.1% SDS running buffer at a pH of 8.3 at 25 mA/gel. Ten microlitres of purified protein eluent from different collected tubes and 2 μl of C-serum from virgin trees were analysed per lane. The gels were routinely stained with 0.1% Coomassie brilliant blue R-250.

The electrophoretic transfer of proteins from SDS–PAGE to a PVDF membrane was based on Towbin et al. (19). The electrode solution was composed of 20 mM Tris base, 150 mM glycine and 20% (v/v) methanol. The electrophoretic transfer was performed at 120 mA/gel for 5 h at room temperature. The localization of bound alkaline phosphatase conjugated antibodies was performed using the BCIP/NBT kit from TIANGEN Biotech Co., Ltd. (China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The controls were performed using a pre-immune serum instead of immune serum.

Production of 37 and 44 kDa protein antiserum

Antiserum production was performed according to Tian et al. (20). The DEAE-sepharose-purified 37 and 44 kDa proteins were isolated by SDS–PAGE. The gel containing either the 37 kDa or the 44 kDa protein was cut out and ground fully in liquid nitrogen. The protein in the gel powder was determined according to the method of Ball (21) and emulsified with Freund’s adjuvant (Sigma). Each of these emulsions was used to immunize two New Zealand male rabbits by hypodermic injection. The antiserum was purified by ammonium sulphate precipitation.

Assay for RP aggregation in vitro

The method for analysing RP aggregation in vitro was performed according to Wititsuwannakul et al. (17) with modifications. In brief, RPs were collected from the bottom of the rubber layer after centrifugation, subsequently dispersed in tris buffered saline (TBS) buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl+0.9% NaCl, pH 7.4) and filtered through a 0.45 μm microporous membrane filter. Thus, the obtained RPs primarily consisted of small RPs. The small RPs were diluted with TBS buffer to an optical density value of ∼2.0–2.5 at 600 nm. The reaction mixture contained 25 μl of small RP suspension and 25 μl of a protein solution of B-serum, C-serum or other proteins as indicated, and 25 μl of TBS buffer was used as a control. The reaction mixture was stained with 0.5% basic fuchsin after being incubated for 30 min at 25°C. The mixture was loaded into a capillary tube with a diameter of 1 mm by means of capillary action, and the bottom of the capillary tube was plugged by modelling clay. The floating RP aggregates were observed under a light microscope after being centrifuged for 5 min at a speed of 5,000 rpm at room temperature.

Assay for the effect of the 44 kDa protein on latex coagulation induced by B-serum and RP aggregation induced by lutoid debris in vitro

The isolation and purification of lutoid debris, as well as B-serum, were performed according to Wang et al. (12). For the latex coagulation assay, fresh latex was diluted 100 times with Tris-HCl buffer (0.1 M Tris-HCL, 10 mM dithiothreitol, pH 7.2) and mixed with different amounts of the 44 kDa protein as indicated in Fig. 3A. For the assay for lutoid debris and RP aggregation, small RPs were diluted with TBS buffer to an optical density value of ∼2.0–2.5 at 600 nm. The diluted RP suspension was mixed with 0.25 mg of lutoid debris and different amounts of the 44 kDa protein. The mixtures were centrifuged at 6,000 rpm for 5 min at room temperature.

Fig. 3.

Effect of the 44 kDa protein on inhibiting latex coagulation caused by C-serum (A) and RP aggregation caused by lutoid debris (B) and hevein (C). a, latex suspension; b, latex suspension mixed with 60 μg of B-serum; c–g, latex suspension mixed with 60 μg of B-serum plus 44 kDa protein in the amounts of 2 μg (c), 4 μg (d), 8 μg (e), 16 μg (f) and 32 μg (g); h, RP suspension; i, lutoid debris; j, RP suspension mixed with lutoid debris; k–o, RP suspension mixed with lutoid debris plus 44 kDa protein in the amounts of 1 μg (k), 2 μg (l), 4 μg (m), 8 μg (n) and 16 μg (o); p, RP suspension mixed with TBS; q, RP suspension mixed with 60 μg of hevein; r–t, RP suspension mixed with 60 μg of hevein plus 44 kDa protein in the amounts of 6 μg (r), 12 μg (s) and 18 μg (t).

MALDI TOF MS analysis

The proteins were identified by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI TOF MS) as described (12). First, the protein was digested in-gel with bovine trypsin according to a reported method (22). After digestion, the protein peptides were collected and vacuum dried. The matrix was prepared by dissolving α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA) in 50% acetonitrile and 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA). Ten microlitres of matrix solution was added into the dried digests and vortexed for 30 min. A 1.5 μl sample of the reconstituted in-gel digest was spotted initially on an Anchorchip target plate (600/384 F, Bruker Daltonics) followed by 1 μl of matrix solution. The dried sample on the target plate was washed twice with 1 μl of 0.1% TFA, left for 30 s before solvent removal and dried for MALDI TOF MS analysis on an Autoflex MALDI TOF/TOF MS instrument (Bruker Daltonics). The spectra were analysed with flexAnalysis software (Version 3.2, Bruker-Daltonics). All spectra were smoothed, and all peptide mass fingerprint spectra were internally calibrated with trypsin autolysis peaks. Then, the measured tryptic peptide masses were transferred through the MS BioTool program (Bruker-Daltonics) as inputs to search against the taxonomy of Viridiplantae (Green Plants) in the nonredundant NCBI database using MASCOT software (Version 2.2). The peptide mass fingerprinting (PMF) search parameters were as follows: 300 parts per million tolerance as the maximum mass error, MH+ monoisotopic mass values, allowance of oxidation (M) modifications, one missed cleavage was allowed, and fixed modification of cysteine by carboxymethyl (carbamidomethylation, C).

Results

Purification and identification of 37 and 44 kDa proteins from C-serum

Proteins in C-serum were precipitated with an increasing amount of (NH4)2SO4 to 50–70%, which was further increased to 70–85% saturation. The proteins were then collected by centrifugation and separated by gel filtration (Fig. 1A and G). Peak 3 consisted of fractions rich in a 37 kDa protein (Fig. 1A) and a 44 kDa protein (Fig. 1G) on the basis of SDS–PAGE (Fig. 1B and H). The fractions of peak 3 were further separated by ion exchange chromatography (Fig. 1C and I). The relatively purified 37 kDa protein and the 44 kDa protein were present in the fractions of peak 4 (Fig. 1C and I) by SDS–PAGE monitoring (Fig. 1D and J), respectively. The 37 and 44 kDa protein bands in SDS–PAGE gels (Fig. 1D and J) were used for MALDI TOF MS identification. The PMF and Mowse score of the 37 kDa protein (Fig. 1E and F) and 44 kDa protein (Fig. 1K and L), as well as related information (supplementary file), are presented. Based on these data, the 37 and 44 kDa proteins were identified as a GAPDH and Hev b 7-like protein, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Purification and identification of the 37 kDa protein (A–F) and 44 kDa protein (G–L). A and G, size-based chromatographic profiles of C-serum protein samples from fractional precipitation of 70–85% (NH)2SO4 (A) and 50–70% (NH)2SO4 (G), successively. C and I, ion exchange chromatographic profile of fractions rich in the 37 kDa protein (C) and 44 kDa protein (I). B, D, H and J, SDS–PAGE profiles of protein samples from fractions of size-based chromatography (B and H) and ion exchange chromatography (D and J). E and K, PMF file of the 37 kDa protein (E) and 44 kDa protein (K). F and L, Mowse score of the 37 kDa protein (F) and 44 kDa protein (L).

Effect of the 44 kDa protein on inhibiting RP aggregation triggered by B-serum and the 37 kDa protein

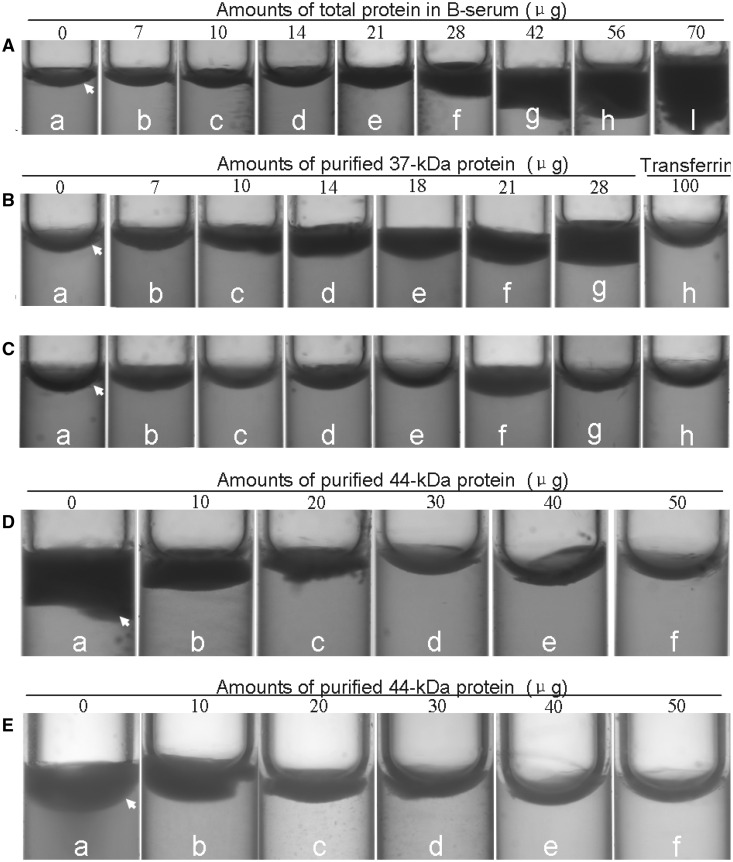

By using the method developed by Witisuwannakul et al. (17), an assay for RP aggregation in vitro was performed. As expected, the B-serum was quite effective on RP aggregation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2A). The effect was more obvious when the amount of the added B-serum proteins was more than 28 μg (Fig. 2A, f). The 37 kDa protein was also effective at inducing RP aggregation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2B). The effect was more obvious when the amount of the added 37 kDa protein was more than 10 μg (Fig. 2B, c). These effects were specific because 100 µg of transferrin had no effect on RP aggregation (Fig. 2B, h). Antibodies raised against the small RP protein (SRPP) inhibited the RP aggregation caused by the 37 kDa protein (Fig. 2C, a–c). The antibodies raised against a 22 kDa vegetative storage protein from litchi, however, had no effect on inhibiting RP aggregation caused by the 37 kDa protein (Fig. 2C, d) or inducing RP aggregation (Fig. 2C, e). Transferrin had no effect on inhibiting 37 kDa protein-induced RP aggregation (Fig. 2C, f) or inducing RP aggregation with increasing amounts (Fig. 2C, g and h). The 44 kDa protein inhibited the RP aggregation triggered by either B-serum (Fig. 2D) or the 37 kDa protein (Fig. 2E) in a dose-dependent manner. Ten micrograms of the 44 kDa protein inhibited the RP aggregation triggered by 42 µg of B-serum proteins (Fig. 2D, b) or 28 µg of the 37 kDa protein (Fig. 2E, b). By increasing the amount of 44 kDa protein, the RP aggregation induced by B-serum (Fig. 2D, b–f) and 37 kDa protein (Fig. 2E, b–f) was dramatically inhibited.

Fig. 2.

Effect of the 44 kDa protein on inhibiting PR aggregation caused by B-serum (A and D), 37 kDa protein (B and E) and SRPP antibodies on inhibiting RP aggregation caused by the 37 kDa protein (C). A, RP aggregation influenced by a RP suspension mixed with TBS buffer (50 mM Tris-Hcl+0.9%NaCl, pH7.4) (a) and different amounts of B-serum (b–i). The amount of B-serum was based on protein concentration. (B) RP aggregation influenced by RP suspension mixed with TBS buffer (a), different amounts of 37 kDa protein (b-g) and 100 μg of transferrin (h). C, RP aggregation influenced by RP suspension mixed with TBS buffer (a), 25 μg of 37 kDa protein (b), 25 μg of 37 kDa protein plus 25 μg of antibodies of SRPP (c), 25 μg of 37 kDa protein plus 25 μg of antibodies for the 22 kDa vegetative storage protein from litchi (d), 25 μg of antibodies for 22 kDa vegetative storage protein from litchi (e), 25 μg of 37 kDa protein plus 25 μg of transferrin (f), 25 μg of transferrin (g) and 50 μg of transferrin (h). D, RP aggregation influenced by RP suspension mixed with 42 μg of B-serum (a) and 42 μg of B-serum plus different amounts of 44 kDa protein (b–f). E, RP aggregation influenced by RP suspension mixed with 28 μg of 37 kDa protein (a) and 28 μg of 37 kDa protein plus different amounts of 44 kDa protein (b–f). Arrow, RP float.

Effect of the 44 kDa protein on preventing B-serum-induced latex coagulation and inhibiting RP aggregation caused by lutoid debris and hevein

The latex suspension was stable within 2 h at room temperature (Fig. 3A, a). The addition of 60 μg of B-serum resulted in latex coagulation within 20 min in the same conditions (Fig. 3A, b). The 44 kDa protein was effective at preventing latex coagulation caused by B-serum in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3A, c–g). It also prevented lutoid debris from combining with small RPs (Fig. 3B). The RP suspension was not layered (Fig. 3B, h), whereas the washed lutoid debris was precipitated (Fig. 3B, i) after centrifugation for 5 min at 6,000 rpm. The centrifugation of the mixture of lutoid debris and RP suspension resulted in low deposit size (Fig. 3B, j). The deposits become more and more evident and the supernatant becomes gradually more turbid with increasing amounts of the 44 kDa protein in the mixture (Fig. 3B, k–o). Hevein’s function on RP aggregation has been previously confirmed (10). The addition of 60 μg of hevein to the RP suspension resulted in obvious RP aggregation (Fig. 3C, p and q). The 44 kDa protein inhibited RP aggregation induced by hevein in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3C, r–t).

Effect of C-serum from an ethrel-treated virgin tree on inhibiting RP aggregation

The application of ethrel on rubber trees significantly prolongs the latex flow. Two days after virgin trees were treated with 2% ethrel, the duration of latex flow lasted for ∼120 min on average (Fig. 4A). As a control, the average duration of latex flow for water-treated virgin trees was only ∼20 min (Fig. 4A). To compare with the effect of TBS buffer on RP aggregation (Fig. 4B, a, f and k), C-serum from either water or ethrel-treated virgin trees had a significant positive effect on RP aggregation (Fig. 4B, b and g) and moreover, the effect of C-serum from the water-treated virgin trees was much stronger (Fig. 4B, b). The addition of polyclonal antibodies against the 37 kDa protein dramatically weakened the RP aggregation caused by the C-serum from water-treated virgin trees (Fig. 4B, c–e) in a dose-dependent manner. In contrast, the addition of polyclonal antibodies of the 44 kDa protein remarkably enhanced RP aggregation caused by the C-serum from ethrel-treated virgin trees in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4B, h–j). TBS buffer (Fig. 4B, k) and the polyclonal antibodies of the 37 kDa protein (Fig. 4B, l) and 44 kDa protein (Fig. 4B, m), as well as the polyclonal antibodies of the 22 kDa vegetative storage protein in Litchi chinensis (Fig. 4B, n), had no effect on RP aggregation. The results suggested that differences in the two types of C-serum-induced RP aggregation were related to the ratio of the 44 kDa protein to the 37 kDa protein in C-serum. Indeed, SDS–PAGE and western blotting analyses showed that the level of the 44 kDa protein in C-serum from ethrel-treated virgin trees was significantly higher than that from water-treated virgin trees, whereas the level of the 37 kDa protein was significantly lower than that from water-treated virgin trees (Fig. 5A–E).

Fig. 4.

Relationship between the prolongation of latex flow duration caused by ethrel application on the virgin tree (A) and the effect of the 44 kDa protein in C-serum on inhibiting RP aggregation as revealed by antibody neutralization (B). a, TBS (50 mM Tris-Hcl+0.9%NaCl, pH7.4) buffer; b–e, C-serum from a water-treated virgin tree mixed with 0 μg (b), 10 μg (c), 50 μg (d) and 100 μg (e) of polyclonal antibodies against the 37 kDa protein. f, TBS buffer; g-j, C-serum from an ethrel-treated virgin tree mixed with 0 μg (g), 10 μg (h), 50 μg (i) and 100 μg (j) of polyclonal antibodies against the 44 kDa protein; k-n, TBS buffer (k) and a mixture of TBS buffer with 100 μg of polyclonal antibodies raised against the 37 kDa protein (l), 44 kDa protein (m) and 22 kDa vegetative storage protein in Litchi chinensis (n), respectively. ET, the virgin tree treated by ethrel; CK, control, that is, the virgin tree treated by water.

Fig. 5.

Effect of ethrel on the level of 44 kDa protein and 37 kDa protein in C-serum. (A) SDS–PAGE profile of C-serum protein samples from water-treated (lane 1) and ethrel-treated (lane 2) virgin trees. Two microlitres of C-serum were loaded per lane. (B–C) western blotting analysis of their duplications with polyclonal antibodies raised against the 44 kDa protein (B) and 37 kDa protein (C), respectively. (D–E) Relative quantitative analysis of 44 kDa protein (D) and 37 kDa protein (E), respectively. M, protein standards.

Discussion

In fresh latex, RPs, lutoids and other minor cellular organelles are suspended in an aqueous serum called the C-serum (23). Therefore, latex-coagulating factors are primarily sequestered in lutoids to avoid direct interaction with RPs although latex-anticoagulating factors in C-serum should be present to prevent RP aggregation. Evidence shows that several proteins in C-serum behave as latex-anticoagulating factors. An α-globulin with a pI of 4.55 in C-serum has been suggested to play a key role in contributing to the colloidal stability of latex and RPs due to its ease of absorption into RPs (24). A HLL-binding protein (HLLBP) in C-serum is suggested to prevent the coagulation of the latex by competitively combining HLL on the lutoid membrane with the SRPP on the RP membrane (17). In this study, a 44 kDa protein is identified as a latex allergen Hev b 7-like protein and has a role in preventing RP aggregation triggered by B-serum (the lutoid inclusions). The Hev b 7 was calculated to compose 0.3% of the total protein of C-serum proteins (25), more than three times the concentration of the 44 kDa protein used in the in vitro reaction system in this study. The nucleotide sequence of Hev b 7 is 51% homologous to potato and 54% homologous to tobacco patatins (26). Hev b 7 has four isoforms with little difference in amino acid sequence and similar properties, such as esterase activity and IgE binding capacity (27). Patatin is a plant PLA2 (an acyl hydrolase) and is thought to function in plants by activating lipoxygenase to generate lipid peroxides that result in the accumulation of antibacterial phytoalexins (26). The 44 kDa protein is likely the same protein as CS-HLLBP (a 40 kDa protein in C-serum). Both of these proteins appear as a major band with similar molecular weight in an SDS–PAGE profile of protein sample from the 70–85% ammonium sulphate fraction. Moreover, both of the proteins inhibit RP aggregation caused by washed lutoid membrane (lutoid debris). Interestingly, an inhibitor of rubber biosynthesis from C-serum also has lipolytic acyl hydrolase (LAH) activity. This inhibitor is similar to Hev b 7 in that they share similar molecular mass, identical peptides from digestion of trypsin and endoproteinase-lys-C, respectively, and homology to patatin, and they both possess esterase lipid acyl hydrolase and acyltransferase activities (25, 28). The effect of this inhibitor on rubber biosynthesis is suggested to be due to the LAH-induced destruction of the integrity of the RP membrane in which the biosynthetic enzymes are thought to be embedded (28). This explanation, however, does not support the effect of the 44 kDa protein on preventing RP aggregation because the destruction of the integrity of the RP membrane will result in RP aggregation (24). It is interesting that a 37 kDa protein in C-serum has an effect on initiating RP aggregation. This protein is a GAPDH-like protein. The GAPDH (EC 1.2.1.12) is an essential enzyme in the glycolytic pathway (29). Considering functions of GAPDH, such as DNA repair, the translational control of gene expression, DNA replication, endocytosis and apoptosis, tolerance to various biotic and abiotic stresses and cellular redox regulation have been suggested (29–32), it should not be surprised that GAPDP (the 37 kDa protein) in laticifers acts as a RP aggregating factor. As the 37 kDa protein and RPs are present in the same environment (C-serum), the 37 kDa protein-triggered RP aggregation seems to be inescapable. In this respect, the inhibition of the 37 kDa protein-triggered RP aggregation by the 44 kDa protein is necessary.

The severed laticifers are widely believed to be plugged by rubber coagulum as a result of RP aggregation caused by the bursting of lutoids (8, 10, 17). However, previously reported evidence suggests the presence of a large ‘protein-network’ together with aggregates of intact RPs at the end of the severed laticifers soon after latex flow stops (33). These may represent two stages of plug formation and implicate the occurrence of a complicated biochemical process. In this study, a 44 kDa protein in C-serum is found to act as a universal antagonist of known factors as B-serum and debris of lutoids and a 37 kDa protein in C-serum that can trigger rubber particle aggregation and latex coagulation. Neutralization of the 44 kDa protein in C-serum from ethrel-treated virgin trees leads to enhanced RP aggregation. It is noted that ethrel application increases the level of the 44 kDa protein whereas decrease the level of the 37 kDa protein in C-serum. Furthermore, there is a high positive correlation between the level of CS-HLLBP (the 40 kDa protein) and rubber yield per tapping (17). Taken together, it is alternatively suggested that the increase in the level of the 44 kDa protein or the ratio of the 44 kDa protein to the 37 kDa protein may be primarily associated with the ethrel-stimulated prolongation of latex flow. The biochemical mechanism for the regulation of the 44 kDa protein on RP aggregation and plug formation at the severed laticifer ends is in progress.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary Data are available at JB Online.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Mr Wu Jilin and Hao Bingzhong for help in paper writing, and PhD Wang Xuchu for skillful mass spectroscopy assistance.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- HLL

Hevea latex lectin

- HLLBP

Hevea latex lectin-binding protein

- LAH

lipolytic acyl hydrolase

- MALDI TOF MS

matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time of flight mass spectrometry

- PMF

peptide mass fingerprinting

- PVDF

polyvinylidene fluoride

- RP

rubber particle

- SDS–PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- SRPP

small rubber particle protein

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31170642; 31070535), the National Basic Research Program of China (2012CB723005) and the earmarked Fund for Modern Agro-Industry Technology Research System (CARS-34-GW1).

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Yeang H.Y., Arif S.A.M., Yusof F., Sunderasan E. (2002) Allergenic proteins of natural rubber latex. Methods 27, 32–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D’Auzac J., Prevot J.C., Jacob J.L. (1995) What’s new about lutoids? A cacuolar system modes from Hevea latex. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 33, 765–777 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kush A. (1994) Isoprenoid biosynthesis: the Hevea factory. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 32, 761–767 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kongsawadworakul P., Viboonjun U., Romruensukharom P., Chantuma P., Ruderman S., Chrestin H. (2009) The leaf, inner bark and latex cyanide potential of Hevea brasiliensis: evidence for involvement of cyanogenic glucosides in rubber yield. Phytochemistry 70, 730–739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin M.N. (1990) The latex of Hevea brasiliensis contains high levels of both chitinases and chitinases/lysozymes. Plant Physiol. 95, 469–476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hao B.Z., Wu J.L. (2004) Biology of laticifers in Hevea and latex production. Chin. J. Trop. Crop 25, 1–7 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wititsuwannakul R., Pasitkul P., Kanokwiroon K., Wititsuwannakul D. (2008) A role for a Hevea latex lectin-like protein in mediating rubber particle aggregation and latex coagulation. Phytochemistry 69, 339–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Southorn W.A. (1968) Latex flow study. I. Electron microscopy of Hevea brasiliensis in the region of the tapping cut. J. Rubb. Res. Inst. Malaya. 20, 176–186 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Southorn W.A., Edwin E.E. (1968) Latex flow studies. II. Influence of lutoids on the stability and flow of Hevea latex. J. Rubb. Res. Inst. Malaya. 20, 187–200 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gidrol X., Chrestin H., Tan H.L., Kush A. (1994) Hevein, a lectin-like protein from Hevea brasiliensis (Rubber tree) is involved in the coagulation of latex. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 9278–9283 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Southorn W.A., Yip E. (1968) Latex flow studies. III. Electrostatic considerations in the colloidal stability of fresh Hevea latex. J. Rubb. Res. Inst. Malaya. 20, 201-215 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang X., Shi M., Wang D., Chen Y., Cai F., Zhang S., Wang L., Tong Z., Tian W.M. (2013) Comparative proteomics of primary and secondary lutoids reveals that chitinase and glucanase play a crucial combined role in rubber particle aggregation in Hevea brasiliensis. J. Proteome Res. 12, 5146–5159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coupe M., Chrestin H. (1989) Physico-chemical and biochemical mechanisms of the hormonal (ethylene) stimulation: early biochemical events induced, in Hevea latex, by hormonal bark stimulation. in Physiology of Rubber Tree Latex. (d’Auzac J., Jacob J.L., Chrestin H, eds.), pp. 295–319, Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xiao X., Luo S., Xu W., Wei X., Liu S. (1999) Effect of microcut system on yield and physiological status of Hevea clone PR107. Chin. J. Trop. Crop. 20, 8–12 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiao X., Cai L. (2003) Effect of ethrel stimulation on metabolism of active oxygen in laticiferous cell. Chin. J. Trop. Crop. 24, 1–7 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Broekaert I., Lee H.I., Kush A., Chua N.H., Raikhel N. (1990) Wound-induced accumulation of mRNA containing a hevein sequence in laticifers of rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 87, 7633–7637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wititsuwannakul R., Pasitkul P., Jewtragoon P., Wititsuwannakul D. (2008) Hevea latex lectin binding protein in C-serum as an anti-latex coagulating factor and its role in a proposed new model for latex coagulation. Phytochemistry 69, 656–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bradford M.M.(1976) A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Towbin H., Staehelin T., Gordon J. (1979) Electrophoretic transfer of protein from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 76, 4350–4354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tian W.M., Wu J.L., Hao B.Z., Hu Z.H. (2003) Vegetative storage proteins in the tropical tree Swietenia macrophylla: seasonal fluctuation in relation to a fundamental role in the regulation of tree growth. Can. J. Bot. 81, 492–500 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ball E.H. (1986) Quantitation of proteins by elution of coomassie brilliant blue R from stained bands after sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Anal. Biochem. 155, 23–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang X., Shi M., Lu X., Ma R., Wu C., Guo A., Peng M., Tian W.M. (2010) Aemethod for protein extraction from different subcellular fractions of laticifer latex in Hevea brasiliensis compatible with 2-DE and MS. Proteome Sci. 8, 35–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arif S.A.M., Hamilton R.G., Yusof F., Chew N.P., Loke Y.H., Nimkar S., Beintema J.J., Yeang H.Y. (2004) Isolation and characterization of the early nodule-specific protein homologe (Hev b 13), an allergenic lipolytic esterase from Hevea brasiliensis latex. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 23933–23941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Archer B.L., Cockbain E.G.(1995). The proteins of Hevea brasiliensis latex. 2. Isolation of the α-globullin of fresh latex serum. Biochem. J. 61, 508–512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sowka S., Wagner S., Krebitz M., Arija-Mad-Arif S., Yusof F., Kinaciyan T., Brehler R., Scheiner O., Breiteneder H. (1998) cDNA cloning of the 43-kDa latex allergen Hev b 7 with sequence similarity to patatins and its expression in the yeast Pichia pastoris. Eur. J. Biochem. 255, 213–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kostyal D.A., Hickey V.L., Noti J.D., Sussman G.L., Beezhold D.H. (1998) Cloning and characterization of a latex allergen (Hev b 7): homology to patatin, a plant PLA2. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 112, 355–362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sowka S., Hafner C., Radaucer C., Focke M., Brehler R., Astwood J.D., Arif S.A.M., Kanani A., Sussman G.L., Scheiner O., Beezhold D.H., Breiteneder H. (1999) Molecular and immunologic characterization of new isoforms of the Hevea brasiliensis latex allergen Hev b 7: evidence of no cross-reactivity between Hev b 7 isoforms and potato patatin and proteins from avocado and banana. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 104, 1302–1310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yusof F., Ward M., Walker J.M. (1998) Purification and characterization of an inhibitor of rubber biosynthesis from C-serum of Hevea brasiliensis latex. J. Rubb. Res. 1, 95–110 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jeong M.J., Park S.C., Kwon H.B., Byun M.O. (2000) Isolation and characterization of the gene encoding glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 278, 192–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sirover M.A. (1996) Emerging new functions of the glycolytic protein, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, in mammalian cells. Life Sci. 58, 2271–2277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berry M.D., Boulton A.A. (2000) Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase and apoptosis. J.Neurosci. Res. 60, 150–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baek D., Jin Y., Jeong J.C., Lee H.J., Moon H., Lee J., Shin D., Kang C.H., Kim D.H., Nam J., Lee S.Y., Yun D.J. (2008) Suppression of reactive oxygen species by glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Phytochemistry 69, 333–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hao B.Z., Wu J.L., Meng C.X., Gao Z.Q., Tan H.Y. (2004) Laticifer wound plugging in Hevea brasiliensis: the role of protein-network with rubber particle aggregations in stopping latex flow and protecting wounded laticifers. J. Rubb. Res. 7, 281–299 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.