Abstract

Shorter axial length observed in patients with primary angle closure glaucoma (PACG) might be due to altered matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP9) activity resulting in ECM remodeling during eye growth and development. This study aimed to evaluate common variants in MMP9 for association with PACG. Six tag SNPs of MMP9 were genotyped in a Chinese sample of 1,030 cases, including 572 PACG and 458 primary angle closure (PAC), and 499 controls. None of 6 SNPs were significantly associated with overall PAC/PACG (P > 0.07) or with PAC/PACG subgroups (Pc > 0.18). Meta-analysis of two non-Chinese studies revealed significant association between rs17576 and PACG (ORs = 0.56, P < 0.0001); however, meta-analysis of our dataset with 4 Chinese datasets did not replicate this association (ORs = 1.23, P = 0.29). Prior significant association for rs3918249 in one Caucasian study (OR = 0.63, P = 0.006) was not replicated in meta-analysis of 3 Chinese studies including this study (ORs = 0.91, P = 0.13). Significant heterogeneity between non-Chinese and Chinese datasets precluded overall meta-analysis for rs17576 and rs3918249 (Q = 0.001 and 0.04 respectively). rs17577 was nominally associated with PACG in one Caucasian study (OR = 1.71, P = 0.02), but not in 3 Chinese studies including our study (ORs = 1.20, P = 0.07). Overall meta-analysis revealed nominal association for rs17577 and PAC/PACG (ORs = 1.26, Pc = 0.05). Meta-analysis did not show significant association between the other SNPs and PAC/PACG (P > 0.47). The largest association study to date did not find significant association between MMP9 and PAC/PACG in Chinese; meta-analysis with other Chinese datasets did not produce significant association. In most instances combination with non-Chinese datasets was not possible except for one variant showing nominally significant association. More work is needed to define the role of MMP9 variants in PACG.

Introduction

Glaucoma is the leading cause of irreversible blindness worldwide, and is characterized by retinal ganglion cell death which results in vision loss [1]. Primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) and primary angle closure glaucoma (PACG) are two major forms of glaucoma. PACG is characterized by the apposition between the peripheral iris and trabecular meshwork, which causes elevated intraocular pressure (IOP). It is estimated that PACG blinds more people than POAG worldwide [2]. PACG is more prevalent in Asian populations, affecting approximately 0.75% of adult Asians [3]. The prevalence of PACG is estimated to be 1.1% in the Chinese population [3]. PACG is more common than previously thought in Caucasian populations. The prevalence of PACG in those 40 years or more is 0.4% in European derived populations [4]. It is estimated that 581,000 people in the U.S. are affected with PACG today, and this is projected to increase by 18% within the next decade [4].

An unusually higher incidence of PACG among siblings of affected patients than the general population suggests that genetic factors may play an important role in the development of PACG [5,6]. However, the genetic basis of PACG is not well understood. Recently, two genome-wide association studies identified four genetic loci for PACG, including ABCC5, COL11A1, PLEKHA7 and an intergenic region between PCMTD1 and ST18 on chromosome 8q [7,8]. In addition, candidate gene studies have evaluated common variants in over 50 genes for association with PACG and related phenotypes. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis highlighted the associations of 10 variants in 8 genes/loci with PACG and related phenotypes, including COL11A1 (rs3753841), HGF (rs17427817 and rs5745718), HSP70 (rs1043618), MFRP (rs2510143 and rs3814762), MMP9 (rs3918249), NOS3 (rs7830), PLEKHA7 (rs11024102) and PCMTD1-ST18 (rs1015213) [9]; however, at least 4 variants of 3 genes in this study (i.e., MFRP, MMP9 and NOS3) only showed nominal association and did not survive the Bonferroni correction for multiple testing (all corrected P [Pc] > 0.05), and thus making the associations of these genes with PACG inconclusive. The equivocal results in this meta-analysis could be due to the relatively small sample sizes and limited statistical power (i.e., only 300–400 cases in total for each variant of the three genes). Further studies with larger samples are required to clarify these associations.

In the present study, to help clarify the association between matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP9) and PACG, we evaluated common MMP9 variants for association with primary angle closure (PAC) and PACG in a large Chinese Han sample. Moreover, we performed a meta-analysis by including this Chinese dataset as well as published results from 5 Chinese studies [10–14] and 2 non-Chinese studies [15,16].

Methods

Cases and controls

A total of 1,030 PAC or PACG cases (PAC/PACG) and 499 controls were recruited from the Eye and Ear Nose Throat Hospital, Fudan University. The case group included 572 patients with PACG and 458 patients with PAC. Among cases, 492 patients were acute PAC/PACG, 496 patients were chronic PAC/PACG, and 42 patients were not able to be classified into either acute or chronic PAC/PACG. A complete eye examination was performed for each patient, including examination of the anterior chamber with a slit-lamp, measurement of intraocular pressure (IOP) by Goldmann applanation tonometry, and assessment of fundus photo. Gonioscopy, anterior chamber depth (ACD), axial length (AXL), and visual field were further examined if PAC or PACG was suspected. ACD, AXL and central corneal thickness (CCT) were measured by A-scan ultrasound pachymetry. According to the definitions from the International Society of Geographical and Epidemiological Ophthalmology (ISGEO) [17], PACG was diagnosed based on the presence of glaucomatous optic neuropathy with a vertical cup-disc ratio (VCDR) of 0.7 or greater, peripheral visual loss, an IOP > 21 mmHg, and the presence of at least two quadrants of iridotrabecular contact in which the trabecular meshwork was not visible on gonioscopy. PAC was diagnosed if trabecular obstruction by the peripheral iris had occurred (IOP > 21 mmHg or peripheral anterior synechiae), but without glaucomatous optic neuropathy. Acute PAC/PACG was defined as an episode with (1) a presenting IOP > 28 mmHg; (2) at least two of the following symptoms: ocular or periocular pain, nausea, vomiting, or an antecedent history of intermittent blurring of vision; and (3) at least three of the following signs: conjunctival injection, corneal epithelial edema, mid-dilated nonreactive pupil, or shallow anterior chamber [18]. Chronic PAC/PACG patients consisted of those with no acute signs or symptoms, but met other criteria of PAC/PACG listed above [19]. Patients with secondary angle closure glaucoma due to uveitis, trauma, neovascularization, or any other optic nerve injury affecting either eye were excluded.

Control subjects had no evidence of PAC/PACG based on clinical exam, no family history of glaucoma, no previous surgeries for glaucoma, and no other eye disorders besides senile cataracts.

All the cases and controls were of self-reported Chinese Han ancestry. Demographic and clinical features of the patients with PAC/PACG and controls were shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical features of cases and controls in this study.

| PAC | PACG | Acute PAC/PACG | Chronic PAC/PACG | Overall PAC/PACG | Controls | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 458 | 572 | 492 | 496 | 1030b | 499 |

| Female (%) | 74.7 | 57.3c | 75.2 | 53.8c | 65.1c | 70.5 |

| Age (year)a | 57.9±11.1d | 57.8±11.8d | 58.0±11.5d | 57.9±11.7d | 57.8±11.5d | 56.0±12.7 |

| IOP at diagnosis (mm Hg) | 28.7±15.7 | 29.3±13.3 | 31.2±16.7 | 27.5±11.6 | 29.0±14.4 | N.A. |

| Maximum IOP (mm Hg) | 31.4±16.2d | 33.1±14.1d | 34.3±17.0d | 31.1±12.9d | 32.4±15.1d | 14.7±2.9 |

| Vertical cup-disc ratio | 0.43±0.12d | 0.88±0.09d | 0.61±0.24d | 0.80±0.20d | 0.69±0.24d | 0.35±0.11 |

| Anterior chamber depth (mm) | 2.43±0.58 | 2.55±0.73 | 2.53±0.84 | 2.48±0.44 | 2.50±0.67 | N.A. |

| Axial length (mm) | 22.1±1.0d | 22.3±1.0d | 22.0±1.0d | 22.4±1.0d | 22.2±1.0d | 24.2±1.7 |

| Center cornea thickness (mm) | 552.2±36.1d | 536.9±34.0d | 548.6±37.7d | 538.8±33.3d | 543.7±35.8d | 528.8±33.6 |

All data were presented as (mean±standard deviation) except gender which was presented as percentage.

Abbreviations: IOP, intraocular pressure; N.A., not available; PAC, primary angle closure; PACG, primary angle closure glaucoma.

a Age at diagnosis for cases and age at enrollment for controls.

b Including 42 patients who were not able to be classified into either acute or chronic PAC/PACG.

c P < 0.05 compared to controls according to Chi-squared test.

d P < 0.05 compared to controls according to Mann-Whitney U test.

This study followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethical committee of Eye and Ear Nose Throat Hospital, Fudan University. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients and controls after explanation of the nature and possible consequences of the study.

Genotyping

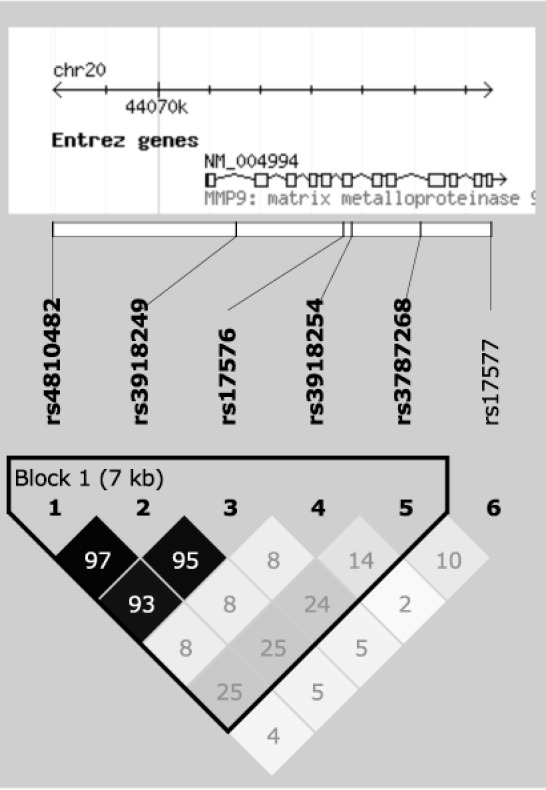

We selected six tag SNPs that captured >95% of alleles at r2 greater than 0.8 across the MMP9 genomic region, including all exons, introns, the 5’- and 3’-UTR, and the 5-kb proximal promoter region (Fig 1). Tag SNPs were selected according to the HapMap CHB+JPT data (version 2, release 21) using Haploview (version 4.2) [20]. The minimum minor allele frequency for checking SNPs was set to 0.1. Genotyping was performed by TaqMan assays (Applied Biosystems [ABI], Foster City, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Fig 1. Linkage disequilibrium plot of the 6 tag SNPs around MMP9 in the Chinese dataset of this study.

The numbers in the diamond indicate r2; black represented r2 = 1, shades of grey indicated 0< r2 <1, and white referred to r2 = 0. Chromosomal positions were based on NCBI build 36.3 (National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, MD).

Statistical analysis

The analysis of CCT, ACD and AXL was performed using the average measurements from both eyes. IOP and VCDR were analyzed using the eye with greater values. Chi-squared test was used to compare the difference in sex between cases and controls. Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the differences in age, IOP, VCDR, ACD, AXL and CCT between cases and controls.

The linkage disequilibrium (LD) plot was generated using Haploview (version 4.2) [20], where squared Pearson correlation coefficient (r2) was used to measure LD. Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium was assessed by the chi-squared test. The association analysis was performed using PLINK (version 1.07) [21] for overall PAC/PACG, the subgroups (PAC, PACG, acute PAC/PACG and chronic PAC/PACG), and the subphenotypes (age at diagnosis, IOP at diagnosis, maximum IOP, VCDR, ACD, AXL and CCT). Logistic or linear regression was used to adjust for age and sex in the association analysis. Multiple comparisons were corrected for the number of SNPs for each analysis using the Bonferroni method.

As described in detail previously [22], haplotype analysis was performed with the standard Expectation-Maximization algorithm and the chi-squared test. P values were obtained from the haplotype-specific test and the omnibus test. The odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated for each of individual haplotypes.

Meta-analysis was performed using the Mantel-Haenszel method, assuming fixed or random effects based on the heterogeneity test results. The heterogeneity between datasets was evaluated using the heterogeneity index (I2) and the Cochran’s Q statistic [23]. The forest plot was generated using Inkscape (Release 0.91, The Inkscape Team, 2015, www.inkscape.org) based on the output from the Review Manager software (RevMan, version 5.3; Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014).

Power analysis for association of MMP9 SNPs with PAC/PACG was performed using the Genetic Power Calculator [24]. The disease prevalence was set as 0.4% for the non-Chinese datasets [4] and 1.1% for the Chinese datasets [3]. The risk allele frequency was set to the same as the marker allele frequency, with 0.38 and 0.34 for the non-Chinese and Chinese datasets based on the allele frequencies of rs17576 in the 1000 Genomes Project [25]. Linkage disequilibrium between the marker and the risk allele was set at D’ = 1.0. The genotypic relative risks for heterozygous (Aa)/high risk homozygous (AA) genotypes were set as 1.78/3.17 and 1.23/1.51 respectively for the non-Chinese and Chinese datasets based on the results of meta-analyses for rs17576, assuming an additive risk model [24].

Power analysis for association of MMP9 SNPs with subphenotypes in PAC/PACG cases was performed using R scripts [26], assuming a linear model. The phenotypic variance explained by additive effects at the marker of interest was set as 1%-5%.

Results

All 6 tag SNPs followed Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium in both case and control groups (P > 0.1). None of the 6 MMP9 tag SNPs were significantly associated with overall PAC/PACG (age and sex adjusted P > 0.07; Table 2) or with the subgroups (age and sex adjusted P > 0.03 and 0.08 for PAC and PACG respectively, Table 2; age and sex adjusted P > 0.04 and 0.08 for acute and chronic PAC/PACG respectively, S1 Table; all Pc > 0.18 after correction for multiple testing).

Table 2. Single-SNP association analysis of MMP9 tag SNPs with PACG in this study.

| MAF | PAC | PACG | Overall PAC/PACG | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP | MA | PAC | PACG | Overall PAC/PACG | Controls | OR (95%CI) | P | OR (95%CI) | P | OR (95%CI) | P |

| rs4810482 | T | 0.27 | 0.29 | 0.28 | 0.31 | 0.80 (0.65–0.98) | 0.03 | 0.94 (0.78–1.14) | 0.51 | 0.86 (0.73–1.02) | 0.11 |

| rs3918249 | T | 0.27 | 0.29 | 0.28 | 0.31 | 0.81 (0.66–0.99) | 0.04 | 0.94 (0.78–1.14) | 0.53 | 0.87 (0.74–1.03) | 0.14 |

| rs17576 | A | 0.28 | 0.30 | 0.29 | 0.31 | 0.85 (0.70–1.04) | 0.12 | 0.96 (0.80–1.16) | 0.68 | 0.90 (0.76–1.06) | 0.27 |

| rs3918254 | T | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 1.24 (0.98–1.57) | 0.08 | 1.16 (0.93–1.45) | 0.19 | 1.21 (0.99–1.48) | 0.08 |

| rs3787268 | A | 0.40 | 0.38 | 0.39 | 0.41 | 0.96 (0.79–1.15) | 0.65 | 0.86 (0.72–1.02) | 0.08 | 0.90 (0.77–1.05) | 0.17 |

| rs17577 | A | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 1.22 (0.93–1.60) | 0.16 | 1.23 (0.95–1.59) | 0.11 | 1.23 (0.98–1.55) | 0.07 |

Abbreviation: MA, minor allele; MAF, minor allele frequency; PAC, primary angle closure; PACG, primary angle closure glaucoma. The Bonferroni corrected significance level was set as 0.008 (0.05/6).

Haplotype analysis of 6 tag SNPs did not find significant association of MMP9 with overall PAC/PACG (P > 0.11; S2 Table), or the subgroups (P > 0.05 and 0.16 for PAC and PACG respectively, S2 Table; P > 0.09 and 0.08 for acute and chronic PAC/PACG respectively; S3 Table).

Analysis of subphenotypes in the PAC/PACG cases did not reveal significant association of MMP9 SNPs with age at diagnosis, IOP at diagnosis, maximum IOP, VCDR, ACD, AXL and CCT (age and sex adjusted P > 0.15; S4 and S5 Tables).

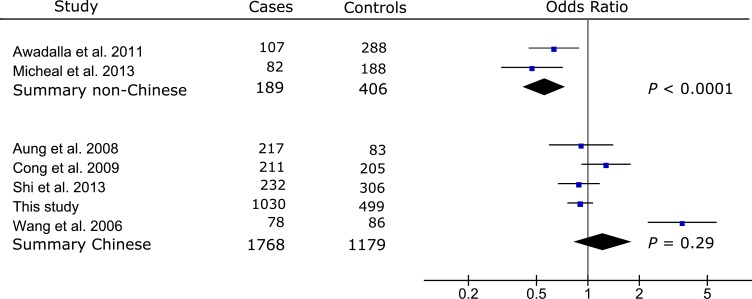

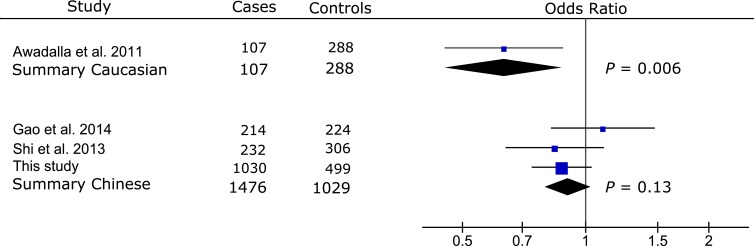

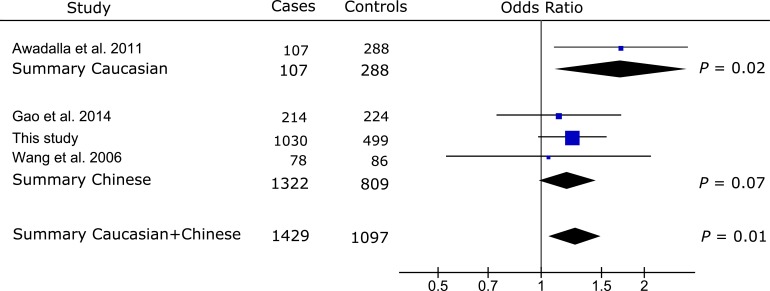

Meta-analysis of the published data from two non-Chinese populations [15,16] showed significant association between rs17576 and PACG (summary OR [ORs] = 0.56, 95% CI: 0.42–0.74, P < 0.0001; Fig 2). Meta-analysis of our Chinese data with the published data from 4 Chinese populations [10–13] did not find significant association of rs17576 with PAC/PACG (ORs = 1.23, 95% CI: 0.83–1.82, P = 0.29; Fig 2). Significant heterogeneity between the non-Chinese and Chinese populations precluded an overall meta-analysis for rs17576 (Q = 0.001, I2 = 90%; Fig 2). Significant association was reported for rs3918249 in one study of the Caucasian population (OR = 0.63, 95% CI: 0.45–0.88, P = 0.006; Fig 3), while no significant association was found for rs3918249 in the meta-analysis of 3 Chinese studies that included this work (ORs = 0.91, 95%CI: 0.80–1.03, P = 0.13; Fig 3). Significant heterogeneity was observed between the Caucasian and Chinese studies (Q = 0.04, I2 = 75%; Fig 3), making it impossible to include the Caucasian data in the meta-analysis of rs3918249. Similarly, rs17577 was nominally associated with PACG in one Caucasian study (OR = 1.71, 95% CI: 1.09–2.67, P = 0.02; Fig 4), but not in three Chinese studies that included our data (ORs = 1.20, 95% CI: 0.99–1.45, P = 0.07; Fig 4). Since no significant heterogeneity was found between the Caucasian and Chinese studies (Q = 0.15, I2 = 52%; Fig 4), an overall meta-analysis of the combined Caucasian and Chinese populations showed nominal association between rs17577 and PAC/PACG (ORs = 1.26, 95%CI: 1.06–1.50, P = 0.01, Pc = 0.05; Fig 4). Meta-analysis did not show significant association between rs3918254 and PAC/PACG (ORs = 1.01, 95%CI: 0.68–1.50, P = 0.95; S1 Fig) or between rs3787268 and PAC/PACG (ORs = 0.95, 95%CI: 0.84–1.08, P = 0.47; S2 Fig).

Fig 2. Meta-analysis with prior studies of the association between rs17576 and PAC/PACG.

Odds ratio was calculated per each increase in minor allele A. The summary odds ratio was 0.56 (95% CI: 0.42–0.74) for the non-Chinese populations and 1.23 (95% CI: 0.83–1.82) for the Chinese populations. Significant heterogeneity between the non-Chinese and Chinese populations precluded an overall meta-analysis for rs17576 (Q = 0.001, I2 = 90%). The Bonferroni corrected significance level was set as 0.01 (0.05/5).

Fig 3. Meta-analysis with prior studies of the association between rs3918249 and PAC/PACG.

Odds ratio was calculated per each increase in minor allele T. The summary odds ratio was 0.63 (95% CI: 0.45–0.88) for the Caucasian population and 0.91 (95% CI: 0.80–1.03) for the Chinese populations. Significant heterogeneity between the Caucasian and Chinese populations precluded an overall meta-analysis for rs3918249 (Q = 0.04, I2 = 75%). The Bonferroni corrected significance level was set as 0.01 (0.05/5).

Fig 4. Meta-analysis with prior studies of the association between rs17577 and PAC/PACG.

Odds ratio was calculated per each increase in minor allele A. The summary odds ratio was 1.71 (95% CI: 1.09–2.67) for the Caucasian population, 1.20 (95% CI: 0.99–1.45) for the Chinese populations, and 1.26 (95%CI: 1.06–1.50) for the combined Caucasian + Chinese populations, respectively. The odds ratios between the Caucasian and Chinese datasets were not significantly heterogeneous (Q = 0.15, I2 = 52%). The Bonferroni corrected significance level was set as 0.01 (0.05/5).

Discussion

In the present study, we evaluated tag SNPs that captured >95% of genetic variation in the MMP9 gene region as well as the proximal 5-kb promoter for association with PACG in a large Chinese case-control dataset. No significant association was found between common SNPs or haplotypes of MMP9 and PAC/PACG in this Chinese sample (Table 2, S2 Table). MMP9 is a member of a large family of endopeptidases which are involved in the remodeling and degradation of extracellular matrix (ECM) [27]. Functional variants have been identified in the MMP9 gene. It is hypothesized that shorter axial length observed in patients with PACG might be due to a change in the MMP9 activity resulting in ECM remodeling during eye growth and development [10].

A coding variant rs17576 in exon 6 of MMP9 leads to the substitution of arginine by glutamine, which might change the enzyme activity of MMP9 [28]. Previous studies have identified significant associations between rs17576 and PACG in one Australian Caucasian population [15], one Pakistani population [16] and one Chinese population [10]. However, three subsequent studies on Chinese patients did not replicate this association [11–13]. Our study also failed to find an association between rs17576 and PAC/PACG in a larger Chinese sample (Table 2, S2 Table). To further evaluate this association, we performed a meta-analysis using our genotype data for the Chinese dataset as well as published data for the Chinese and non-Chinese datasets. Our meta-analysis revealed significant association between rs17576 and PACG in the non-Chinese populations but not in the Chinese populations (Fig 2). Significant heterogeneity between the non-Chinese and Chinese datasets was observed for rs17576 precluding an overall meta-analysis for this SNP (Fig 2). Notably, the risk allele is “G” in the non-Chinese populations, which is different from that in the Chinese populations (i.e., “A”). Such “flip-flop” associations may be due to population-specific effects [29], which have been well documented in genetic association studies such as the association of LOXL1 with exfoliation syndrome [30–32]. Alternatively, the limited sample sizes in the non-Chinese populations might have biased the observed associations between rs17576 and PACG. Further analyses using larger samples or other populations such as Africans will be helpful to clarify this issue.

The findings of significant association between common MMP9 variants and PACG in the non-Chinese populations but not in the Chinese populations were further supported by the results of additional two SNPs in MMP9, rs3918249 (Fig 3) and rs17577 (Fig 4). Both rs3918249 and rs17577 were reported to be significantly associated with PACG in a Caucasian study [15]. However, meta-analyses of our data with the published data from the Chinese populations [10,13,14] did not identify significant association of rs3918249 and rs17577 with PAC/PACG (Figs 3 and 4). An overall meta-analysis of the combined Caucasian and Chinese populations revealed nominal association for rs17577 (Pc = 0.05; Fig 4). Our meta-analysis of the combined Caucasian and Chinese datasets did not find significant association of rs3918254 and rs3787268 with PAC/PACG (S1 and S2 Figs), suggesting that these SNPs are not likely to contribute to the disease. Alternatively, the relatively low frequency of the risk allele for rs3918254 might have prevented us from detecting the association due to insufficient statistical power, particularly in the Caucasian population.

Polymorphisms in the promoter region of MMP9 have been reported to affect the gene transcription [16]. The promoter region has been poorly investigated in previous association studies for MMP9 and PACG. Only one SNP, rs3918242, located at 1,562 base pairs upstream of the MMP9 start codon, was investigated in the Pakistani study [16], while promoter region SNPs were not included in other studies [10–15].The present study is the first time that an association between the MMP9 promoter region and PAC/PACG has been evaluated using tag SNPs. We did not identify significant association between the MMP9 promoter region and PAC/PACG in the Chinese dataset (Table 2), consistent with the results from the Pakistani study [16]. These results suggest that the MMP9 promoter may not contribute to PACG risk, although further studies using larger datasets are required to confirm these findings.

A major limitation of previous MMP9 association studies is the relatively small sample sizes (no more than 300 in either case or control group). In this study, we enrolled a larger sample (1,030 cases and 499 controls), making it the largest study on MMP9 common variants and PAC/PACG to date. Our meta-analysis of rs17576 suggests that genetic effects of MMP9 variants are likely to be modest and on the order of 1.78/3.17 and 1.23/1.51 for Aa/AA in the non-Chinese and Chinese datasets respectively (Fig 2). We estimated that we had 98% of power in all the non-Chinese datasets (189 cases and 406 controls), 48% of power in our Chinese dataset (1,030 cases and 499 controls), and 88% of power in all the Chinese datasets (1,768 cases and 1,179 controls) to detect this modest genetic effect [24]. Notably, the GWAS in the Chinese populations by Vithana et al. (1,854 cases and 9,608 controls in the discovery dataset) had only 63% power to detect the association between rs17576 and PACG, and this may explain why this study did not identify significant association [8].

Our analysis of subphenotypes in the PAC/PACG cases did not find significant association of MMP9 variants with age at diagnosis, IOP at diagnosis, maximum IOP, VCDR, ACD, AXL and CCT (S4 and S5 Tables), suggesting that common variants in MMP9 might not contribute to the disease severity. We estimated that we had 71.6%-99.9% of power to detect the genetic effect of MMP9 SNPs on these quantitative subphenotypes, assuming the phenotypic variance explained by additive effects at the marker of interest as 1%-5%.

Conclusions

We have evaluated common variants in MMP9 as genetic risk factors for PAC/PACG. This is the largest association study on MMP9 and PAC/PACG to date. Prior results suggest that common MMP9 variants may contribute to the modest risk for PACG in the non-Chinese population but our analysis suggests this not the case in the Chinese population. Additional studies using larger datasets will be necessary to confirm these population-specific findings.

Supporting Information

Odds ratio was calculated per each increase in minor allele A. The summary odds ratio was 2.68 (95% CI: 0.17–43.00) for the Caucasian population, 0.99 (95% CI: 0.65–1.52) for the Chinese populations, and 1.01 (95%CI: 0.68–1.50) for the combined Caucasian + Chinese populations, respectively. The odds ratios between the Caucasian and Chinese datasets were not significantly heterogeneous (Q = 0.49, I2 = 0%). The Bonferroni corrected significance level was set as 0.01 (0.05/5).

(DOCX)

Odds ratio was calculated per each increase in minor allele A. The summary odds ratio was 1.26 (95% CI: 0.86–1.86) for the Caucasian population, 0.92 (95% CI: 0.81–1.06) for the Chinese populations, and 0.95 (95%CI: 0.84–1.08) for the combined Caucasian + Chinese populations, respectively. The odds ratios between the Caucasian and Chinese datasets were not significantly heterogeneous (Q = 0.13, I2 = 56%). The Bonferroni corrected significance level was set as 0.01 (0.05/5).

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

The Chinese samples used for the analyses described in this manuscript were obtained from the Biobank of Eye & Ear Nose Throat Hospital, Fudan University. We would like to thank all the participants for their valuable contribution to this research.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported in part by the Funds for International Cooperation and Exchange of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81020108017) (XS) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (81570887) (YC). A Harvard Medical School Ophthalmology Distinguished Scholar Award supports LRP. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Quigley HA, Broman AT. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006; 90: 262–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quigley HA, Congdon NG, Friedman DS. Glaucoma in China (and worldwide): changes in established thinking will decrease preventable blindness. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001; 85: 1271–1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng JW, Zong Y, Zeng YY, Wei RL. The prevalence of primary angle closure glaucoma in adult Asians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014; 9: e103222 10.1371/journal.pone.0103222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Day AC, Baio G, Gazzard G, Bunce C, Azuara-Blanco A, Munoz B, et al. The prevalence of primary angle closure glaucoma in European derived populations: a systematic review. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012; 96: 1162–1167. 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-301189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lowe RF. Primary angle-closure glaucoma. Inheritance and environment. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1972; 56: 13–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amerasinghe N, Zhang J, Thalamuthu A, He M, Vithana EN, Viswanathan A, et al. The heritability and sibling risk of angle closure in Asians. Ophthalmology. 2011; 118: 480–485. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.06.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nongpiur ME, Khor CC, Jia H, Cornes BK, Chen LJ, Qiao C, et al. ABCC5, a gene that influences the anterior chamber depth, is associated with primary angle closure glaucoma. PLoS Genet. 2014; 10: e1004089 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vithana EN, Khor CC, Qiao C, Nongpiur ME, George R, Chen LJ, et al. Genome-wide association analyses identify three new susceptibility loci for primary angle closure glaucoma. Nat Genet. 2012; 44: 1142–1146. 10.1038/ng.2390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rong SS, Tang FY, Chu WK, Ma L, Yam JC, Tang SM, et al. Genetic Associations of Primary Angle-Closure Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2016. February 4 pii: S0161-6420(15)01530-4. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.12.027 [Epub ahead of print] . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang IJ, Chiang TH, Shih YF, Lu SC, Lin LL, Shieh JW, et al. The association of single nucleotide polymorphisms in the MMP-9 genes with susceptibility to acute primary angle closure glaucoma in Taiwanese patients. Mol Vis. 2006; 12: 1223–1232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aung T, Yong VH, Lim MC, Venkataraman D, Toh JY, Chew PT, et al. Lack of association between the rs2664538 polymorphism in the MMP-9 gene and primary angle closure glaucoma in Singaporean subjects. J Glaucoma. 2008;17: 257–258. 10.1097/IJG.0b013e31815c3aa5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cong Y, Guo X, Liu X, Cao D, Jia X, Xiao X, et al. Association of the single nucleotide polymorphisms in the extracellular matrix metalloprotease-9 gene with PACG in southern China. Mol Vis. 2009; 15: 1412–1417. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shi H, Zhu R, Hu N, Shi J, Zhang J, Jiang L, et al. Association of frizzled-related protein (MFRP) and heat shock protein 70 (HSP70) single nucleotide polymorphisms with primary angle closure in a Han Chinese population: Jiangsu Eye Study. Mol Vis. 2013; 19: 128–134. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao XJ, Hou SP, Li PH. The association between matrix metalloprotease-9 gene polymorphisms and primary angle-closure glaucoma in a Chinese Han population. Int J Ophthalmol. 2014; 7: 397–402. 10.3980/j.issn.2222-3959.2014.03.02 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Awadalla MS, Burdon KP, Kuot A, Hewitt AW, Craig JE. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 genetic variation and primary angle closure glaucoma in a Caucasian population. Mol Vis. 2011; 17: 1420–1424. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Micheal S, Yousaf S, Khan MI, Akhtar F, Islam F, Khan WA, et al. Polymorphisms in matrix metalloproteinases MMP1 and MMP9 are associated with primary open-angle and angle closure glaucoma in a Pakistani population. Mol Vis. 2013; 19: 441–447. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foster PJ, Buhrmann R, Quigley HA, Johnson GJ. The definition and classification of glaucoma in prevalence surveys. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002; 86: 238–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee KY, Rensch F, Aung T, Lim LS, Husain R, Gazzard G, et al. Peripapillary atrophy after acute primary angle closure. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007; 91: 1059–1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alsagoff Z, Aung T, Ang LP, Chew PT. Long-term clinical course of primary angle-closure glaucoma in an Asian population. Ophthalmology. 2000; 107: 2300–2304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005; 21: 263–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007; 81: 559–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fan BJ, Liu K, Wang DY, Tham CC, Tam PO, Lam DS, et al. Association of polymorphisms of tumor necrosis factor and tumor protein p53 with primary open-angle glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010; 51: 4110–4116. 10.1167/iovs.09-4974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003; 327: 557–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Purcell S, Cherny SS, Sham PC. Genetic Power Calculator: design of linkage and association genetic mapping studies of complex traits. Bioinformatics. 2003; 19: 149–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.1000 Genomes Project Consortium, Abecasis GR, Altshuler D, Auton A, Brooks LD, Durbin RM, et al. A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature. 2010; 467: 1061–1073. 10.1038/nature09534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria: 2015. Available: http://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nagase H, Woessner JF Jr. Matrix metalloproteinases. J Biol Chem. 1999; 274: 21491–21494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang B, Henney A, Eriksson P, Hamsten A, Watkins H, Ye S. Genetic variation at the matrix metalloproteinase-9 locus on chromosome 20q12.2–13.1. Hum Genet. 1999; 105: 418–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin PI, Vance JM, Pericak-Vance MA, Martin ER. No gene is an island: the flip-flop phenomenon. Am J Hum Genet. 2007; 80: 531–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams SE, Whigham BT, Liu Y, Carmichael TR, Qin X, Schmidt S, et al. Major LOXL1 risk allele is reversed in exfoliation glaucoma in a black South African population. Mol Vis. 2010; 16: 705–712. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dubey SK, Hejtmancik JF, Krishnadas SR, Sharmila R, Haripriya A, Sundaresan P. Lysyl oxidase-like 1 gene in the reversal of promoter risk allele in pseudoexfoliation syndrome. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014; 132: 949–955. 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang L, Yu Y, Fu S, Zhao W, Liu P. LOXL1 gene polymorphism with exfoliation syndrome/exfoliation glaucoma: a meta-analysis. J Glaucoma. 2016; 25: 62–94. 10.1097/IJG.0000000000000128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Odds ratio was calculated per each increase in minor allele A. The summary odds ratio was 2.68 (95% CI: 0.17–43.00) for the Caucasian population, 0.99 (95% CI: 0.65–1.52) for the Chinese populations, and 1.01 (95%CI: 0.68–1.50) for the combined Caucasian + Chinese populations, respectively. The odds ratios between the Caucasian and Chinese datasets were not significantly heterogeneous (Q = 0.49, I2 = 0%). The Bonferroni corrected significance level was set as 0.01 (0.05/5).

(DOCX)

Odds ratio was calculated per each increase in minor allele A. The summary odds ratio was 1.26 (95% CI: 0.86–1.86) for the Caucasian population, 0.92 (95% CI: 0.81–1.06) for the Chinese populations, and 0.95 (95%CI: 0.84–1.08) for the combined Caucasian + Chinese populations, respectively. The odds ratios between the Caucasian and Chinese datasets were not significantly heterogeneous (Q = 0.13, I2 = 56%). The Bonferroni corrected significance level was set as 0.01 (0.05/5).

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.