Abstract

Skull base tumors form a highly heterogeneous group. As there are several structures in this anatomical site, a large number of different primary malignancies might develop, as well as a variety of secondary (metastatic) tumors. In this article, the most common malignancies are presented, along with a short histopathologic description. For some entities, an immunohistochemical profile is also given that should be helpful in proper diagnosis. As many pathologic diagnoses nowadays also include genetic studies, the most common genetic abnormalities in skull base tumors are presented.

Keywords: Skull base tumors, Histopathology, Malignant, Benign

1. Introduction

Tumors of the skull base are a distinct group and, unlike in other cases (e.g. organ specific), they are grouped according to their anatomic location which is used by surgeons. Usually, the pathologic classification refers to tumors’ origin, such as the epidermis, bronchial epithelium or soft tissues. Such classification roughly introduces two groups of tumors: epithelial and non-epithelial, according to their origin. In the skull base, one can find bone, peripheral nerves, large vessels and soft tissues from which different tumors could arise. Additionally, as there are plenty of surrounding structures (e.g. the central nervous system, sinuses, pharynx, etc.), the number of possible tumors that could grow into the skull base region, along with their specific diagnoses, increases. Of course, benign as well as malignant tumors could grow in all of the aforementioned situations. Moreover, at the skull base, we may also find metastases. Taking into consideration all of the above, the pathology of tumors in this anatomical region becomes a challenging issue.

From the clinical point of view, tumors are most commonly grouped according to their anatomical occurrence. In the case of skull base tumors, this allows us to group tumors according to whether they grow within or around the anterior, middle or posterior cranial fossa. Such an approach is presented in the majority of clinical descriptions (see Table 1).1, 2, 3 However, specific tumors (e.g. meningioma, neuroma or chordoma) may develop in all the sites and the morphological picture is similar in all locations. This review is focused on tumors that might develop or invade the skull base region, and where the standard classification would be difficult to apply. In the next section, selected most common tumors are presented with an indication of their most common location.4, 5 As this issue of the journal has a review standard, because of the encyclopedic character of the article, the following tumor descriptions could be given in alphabetic order, although it would perhaps be more appropriate to present lesions according to their histogenesis. As such, the most suitable classification includes tumors grouped as follows: epithelial, soft tissue, tumors of the bones and cartilage, neuroectodermal and hematopoietic.

Table 1.

Tumors of skull base and their distribution in relations to anatomic localization (related to anterior, middle and posteriori cranial fossa).

| Anterior | Middle | Posterior |

|---|---|---|

| Primary and secondary tumors | Chordoma | Paraganglioma |

| Esthesioneuroblastoma | Chondrosarcoma | Neurilemoma |

| Chondroma | Meningioma | Meningioma |

| Chondrosarcoma | Neurilemoma | Chondrosarcoma |

| Tumors invading from adjacent structures | Paraganglioma | Chordoma |

| Carcinoma (mainly squamous cell carcinoma from nasal cavity) | Glioma | |

| Adenoid cystic carcinoma | Teratoma | |

| Lymphoma | Squamous cell carcinoma | |

| Plasmocytoma | Plasmocytoma | |

| Melanoma malignoma | Lymphoma | |

| Pituitary gland tumors (most common: prolactioma) | Metastatic tumors | |

| Craniopharyngioma | ||

| Lipoma | ||

| Hemangioma | ||

| Chordoma | ||

| Neurilemoma | ||

| Teratoma | ||

| Metastatic tumors |

2. Tumors of epithelial origin

2.1. Squamous cell carcinoma

Definition: A malignant epithelial tumor with squamous cell differentiation.

Epidemiology: Depends on the site of the primary tumors (ear or temporal bone, gnathic bones, larynx, oropharynx, sinonasal tract, salivary glands). Usually occurring in middle aged or older adults. Currently, together with the increased incidence of HPV infection, tumors develop in younger patients. Metastatic tumors also occur.6, 7

Morphologic picture: Histologically, there are recognized subtypes of squamous cell carcinoma such as: squamous keratinized, squamous non-keratinized, basaloid or adenosquamous carcinomas. In all cases, the microscopic features or immunohistochemical profile (expression of cytokeratins and p63) should indicate some degree of squamous differentiation. A full morphological diagnosis should include an examination of HPV infection status, either by direct immunostaining for HPV or for p16 (which is activated in HPV-related tumors).

Differential diagnosis: The presence of keratin (extracellular or intracellular) in some squamous cell carcinomas makes diagnosis easier. In cases with poor differentiation, regardless of the site of origin of the tumor, especially in those cases with predominant spindle cells, differentiation between sarcoma and inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor should be performed. Usually, the application of a panel of immunohistochemical stains using epithelial markers (cytokeratins, p40, p63) and mesenchymal markers (vimentin, CD34, SMA) is sufficient for proper diagnosis.8, 9, 10

2.2. Nasopharyngeal carcinomas

Definition: Carcinoma developing in the nasopharyngeal mucosa with features of squamous cell differentiation, according to the WHO classification.1

Epidemiology: The peak incidence is in the 5th and 6th decades, with a twofold male predominance. The risk of tumor development increases with EBV infection.

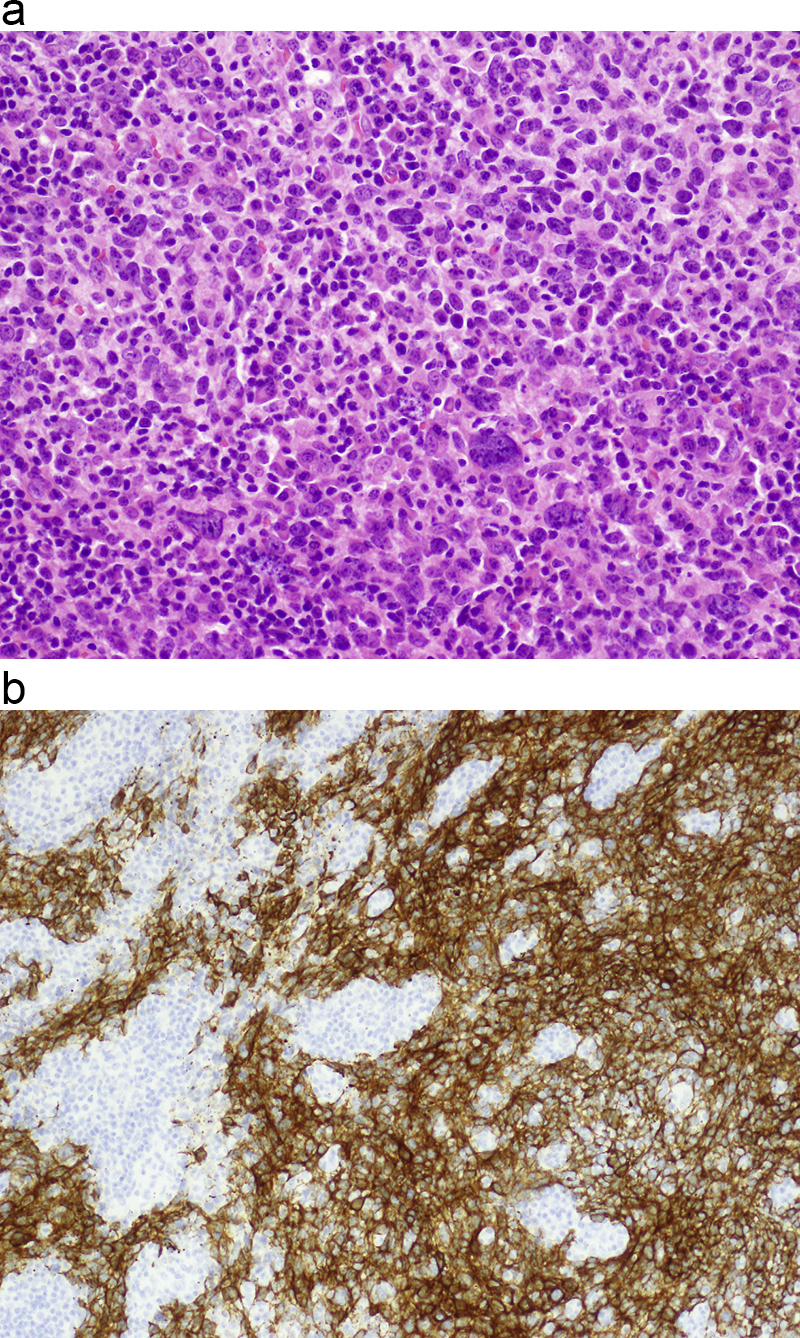

Morphologic picture: The tumor is composed of areas (islands, sheets or trabeculae) of carcinoma (depending of the subtype, with squamous, basaloid or transitional cell type appearance), which are admixed with variable amounts of lymphocytes (Fig. 1a and b).

Fig. 1.

(a) In nasopharyngeal carcinoma, the two components are mixed. Tumor cells of low maturation level, as in the presented tissue sample, are distributed/infiltrating the stroma, which is rich in lymphocytes. Hematoxylin and eosin staining, primary objective magnification 20×. (b) In this example, by means of immunohistochemical procedures with cytokeratin markers (CK 5/6), the squamous cell carcinoma component is made clearly visible against a dense lymphocytic infiltrate. Primary objective magnification 10×.

Other important notes: Other names used include synonyms: lymphoepithelioma, lymphoepithelial carcinoma or Schmincke type lymphoepithelioma. The same terminology is used for such entities as: nonkeratinizing carcinoma, keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma and basaloid squamous cell carcinoma.

Differential diagnosis: This tumor belongs to a group of poorly differentiated malignancies. The first differentials should be made with diffuse large B cell lymphoma (some cells might have an epithelioid appearance, but express B-cell markers), malignant melanoma (some cases show clearly visible intracytoplasmic pigment and are positive for HMB45, S100 and melan-A), and rhadomyosarcoma (mainly by use of muscle differentiation markers including: desmin, MyoD1 or Myf4). Differentiation with other types of nonkeratinizing carcinoma is done by confirmation of viral infection: nasopharyngeal carcinoma is EBV positive, while other carcinomas could be HPV-related (confirmed by p16 staining).8, 11, 12, 13, 14

2.3. Craniopharyngioma

Definition: A usually benign tumor developing from Rathke's pouch/cyst structures.

Epidemiology: Up to 30% of the tumors develop before puberty.

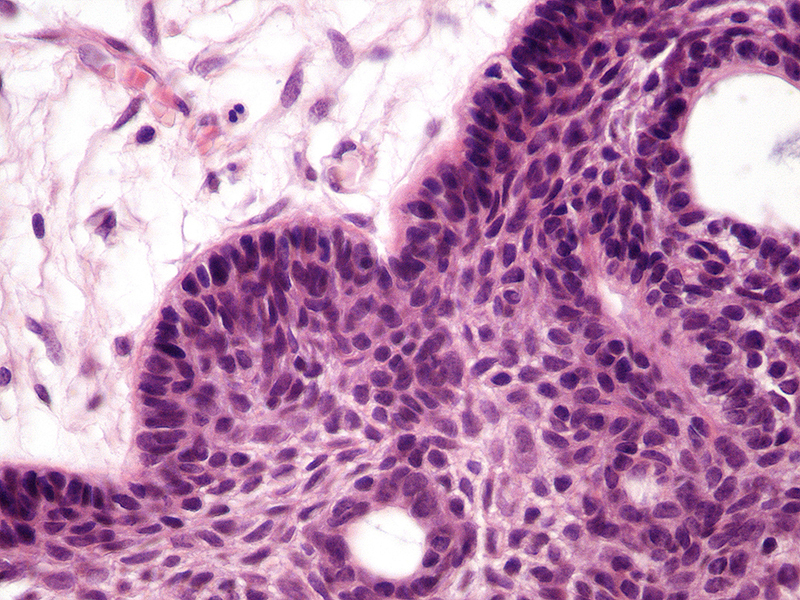

Morphologic picture: According to the histologic picture, three types are recognized: adamantinomatous (so called “pediatric” as it typically occurs before the age of 14) and papillary (also called “adult type”). A mixed subtype also exists. The pediatric type is usually poorly circumscribed. The epithelial cells form nests or trabeculae with palisading at the periphery (Fig. 2). In cystic areas, abundant keratin is noted. In the adult type, papillary structures are lined by squamous epithelium resembling squamous cell papilloma. In the adult type, in contrast to the pediatric type, no “wet” keratin, calcifications, or xanthogranulomatous inflammation is to be found.15, 16

Fig. 2.

Craniopharyngioma is composed of epithelial cells which form nests or trabeculae with palisading at the periphery. Hematoxylin and eosin staining. Primary objective magnification 10×.

Other important notes: Recurrences have been recorded after incomplete excision. Malignant transformation is related to development of squamous cell carcinoma. Involvement of the skull base might follow the development of a tumor in the suprasellar area, with penetration down to the bone, or in very rare cases, primary craniopharyngioma developing in the nasopharynx.17

Differential diagnosis: As the epithelium of the canal in cases of craniopharyngioma may show some degree of atypia, squamous cell carcinoma should be taken into consideration. Demonstration of p53 should be helpful in such cases, as this marker is highly expressed in squamous cell carcinoma.6, 18, 19

2.4. Cholesteatoma

Definition: A benign tumor composed of keratin-filled cysts occurring in the middle (more commonly) or external ear. These tumors may develop as either a congenital malformation (entrapment of squamous epithelium within bone) or as an acquired lesion (when injury or retraction of the tympanic membrane occurs).

Epidemiology: Usually young males.

Morphologic picture: The tumor may range from a small to rather large cyst. Microscopically, the cyst is filled with keratin masses. Around the lesion, chronic inflammatory infiltrate forms a part of the picture. Granulation tissue as well giant multinucleated cells of foreign body (keratin or fragment of destroyed bone) type are also found. In older lesions cholesterol crystals can be found.20

Other important notes: As tumors of large diameter might lead to destruction of the bone, a careful differential diagnosis with squamous cell carcinoma should be performed. In the latter entity, cellular atypia and desmoplastic stromal reactions support the diagnosis of a malignant lesion. Some of such lesions may be HPV positive.

Differential diagnosis: Taking into account the clinical picture and the presence of cholesterol crystals, the diagnosis should be straightforward. However, in cases with high cellular atypia and reactive (desmoplastic) changes within the stroma, a differential diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma should be explored. In order to make a diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma “true” stromal invasion must be found. The presence of metastases (typical for carcinoma) makes the diagnosis much easier.18

3. Salivary gland tumors

Definition: This is a very heterogeneous group of tumors, both benign and malignant (see Table 2 for common entities). A detailed description of the lesions is presented elsewhere.

Table 2.

WHO classification of selected salivary gland tumors.

| Benign tumors |

| Pleomorphic adenoma |

| Myoepithelioma |

| Basal cell adenoma |

| Warthin tumor |

| Oncocytoma |

| Canalicular adenoma |

| Sebaceous adenoma |

| Lymphadenoma |

| Sebaceous |

| Non-sebaceouss |

| Ductal papillomas |

| Inverted ductal papilloma |

| Intraductal papilloma |

| Sialadenoma papilliferum |

| Cystadenoma |

| Malignant epithelial tumors |

| Acinic cell carcinoma |

| Mucoepidermoid carcinoma |

| Adenoid cystic carcinoma (Cylindroma) |

| Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma |

| Epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma |

| Clear cell carcinoma, NOS |

| Basal cell adenocarcinoma |

| Sebaceous carcinoma |

| Sebaceous lymphadenocarcinoma |

| Cystadenocarcinoma |

| Low-grade cribriformed cystadenocarcinoma |

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma |

| Oncocytic carcinoma |

| Salivary duct carcinoma |

| Adenocarcinoma, NOS |

| Myoepithelial carcinoma |

| Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma |

| Carcinosarcoma |

| Metastasizing pleomorphic adenoma |

| Squamous cell carcinoma |

| Small cell carcinoma |

| Large cell carcinoma |

| Lymphoepithelial carcinoma |

| Sialoblastoma |

3.1. Adenoid cystic carcinoma

Definition: The alternative, former, name is cylindroma (based on the histologic structure). Primary tumors can develop within the salivary glands (usually minor ones) or, less commonly, in the mucosa of the upper respiratory tract, including the nose and sinuses. Primary lesions can also develop in the skin and, notably, the most common localization is the head and neck area. The tumor arises from the glandular structures of the salivary glands and from the apocrine glands of the skin. Previously, it was associated with eccrine differentiation.5, 18

Epidemiology: The tumor is most common in mature adults, incidence peaks between the 5th and 6th decades. There is a slight male predominance.

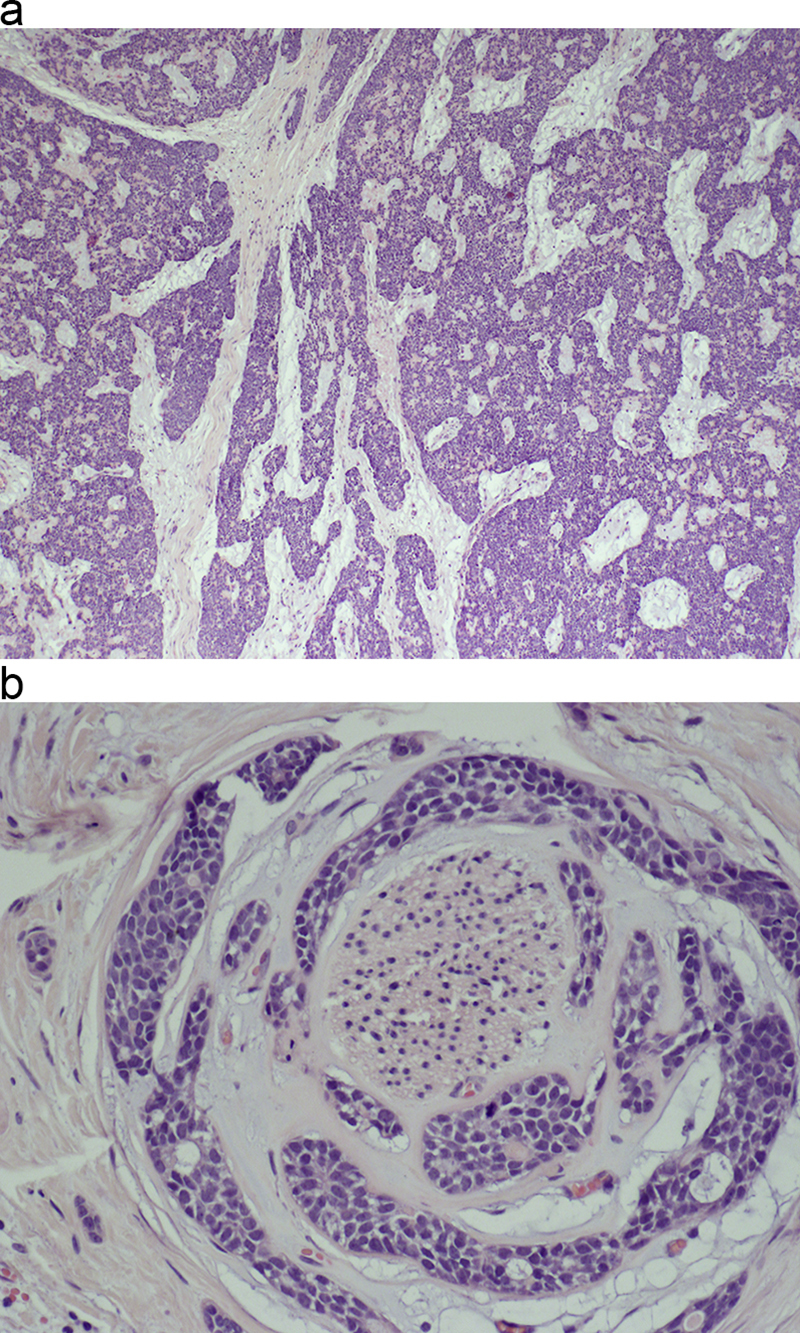

Morphologic picture: Macroscopically, the tumors range from around one to more than 8 cm and have poorly defined borders. Microscopically, there are recognized variants: solid, cribriform and tubular (Fig. 3a and b). Some authors also include a mixed pattern. Regardless of the variant, the tumor is composed of small uniform cells with dark nuclei and scant cytoplasm. Usually, there are visible pseudoglandular spaces filled by PAS positive material and with the appearance of basement material in transmission electron microscopy studies. Sometimes, there are true glandular lumina containing mucin. One of the hallmarks of this tumor is its peculiar tendency for perineural invasion, which was, until recently, considered pathognomonic for its diagnosis. However, other tumors with perineural invasion have now been recognized. The immunohistochemical profile of adenoid cystic carcinoma is as follows: CK7+, CK20 negative, CD117+ (usually cells in ducts), S100+, alpha-1-antichymotrypsin+ (usually cells in ducts).

Fig. 3.

(a) A typical low-power view of carcinoma adenoides cysticum with a partially cribriform and partially solid pattern. Pseudoglandular structures are easily recognized. Hematoxylin and eosin staining, primary objective magnification 4×. (b) On microscopic examination of carcinoma adenoides cysticum, a peculiar tendency for nerve invasion is usually found. Hematoxylin and eosin staining, primary objective magnification 20×.

Other important notes: Regardless of the rather indolent microscopic picture, the tumor can recur, even after several years, and seldom gives lymph node metastases. The best prognosis is for the tubular variant with an expected survival of almost 40% after 15 years.

Differential diagnosis: The diagnosis of primary salivary gland adenoid cystic carcinoma should be made after exclusion of metastases from its skin related counterpart. Other differentials include salivary gland low-grade polymorphous adenocarcinoma, basal cell adenocarcinoma or basal cell adenoma. In the majority of cases, examination of multiple samples from a tumor should be enough to make a proper tumor discrimination. I in some cases the immunoprofile, especially the CGFP and CD117 status, could be helpful. Worthy of note is the issue of neural invasion, which was previously regarded as being exclusively found in adenoid cystic carcinoma, but now described by many authors in other salivary gland tumors.18, 20, 21, 22

4. Soft tissue, bone, and cartilage tumors

4.1. Hemangioma

Definition: A benign tumor derived from the endothelium of blood vessels.

Epidemiology: Occur at any age, but occurrence during childhood and in adolescent males is most common.

Morphologic picture: The tumor is composed of vascular channels lined by endothelial cells. According to the size of the vessels, two types are recognized: capillary (showing channels with a small luminal diameter) (Fig. 4) and cavernous (when large, dilated vascular spaces are observed). Such tumors may be lobulated. The endothelial cells are benign looking, and mitoses are common, but never atypical. The immunohistochemical profile includes reactivity with CD31, CD34 and factor VIII (von Willebrandt factor).

Fig. 4.

In this case of hemangioma, multiple small blood vessels are clearly visible. The newly formed capillaries are lined by cuboidal endothelial cells. Hematoxylin and eosin staining, primary objective magnification 20×.

Other important notes: As the morphology overlaps with other entities, the differential diagnosis includes: granulation tissue, vascular malformations and teleangiectasias.

Differential diagnosis: The microscopic features are rather unique; however, in some cases they could be differentiated from lymphangioma using podoplanin (antibody D2-40) against endothelial cells of the lymphatics.2, 18

4.2. Lipoma

Definition: A benign soft tissue tumor composed of mature fat. Several subtypes are recognized according to the stage of differentiation, from stem cells to mature adipocytes.

Epidemiology: Lipoma occurs most commonly between 40 and 60 years of age.

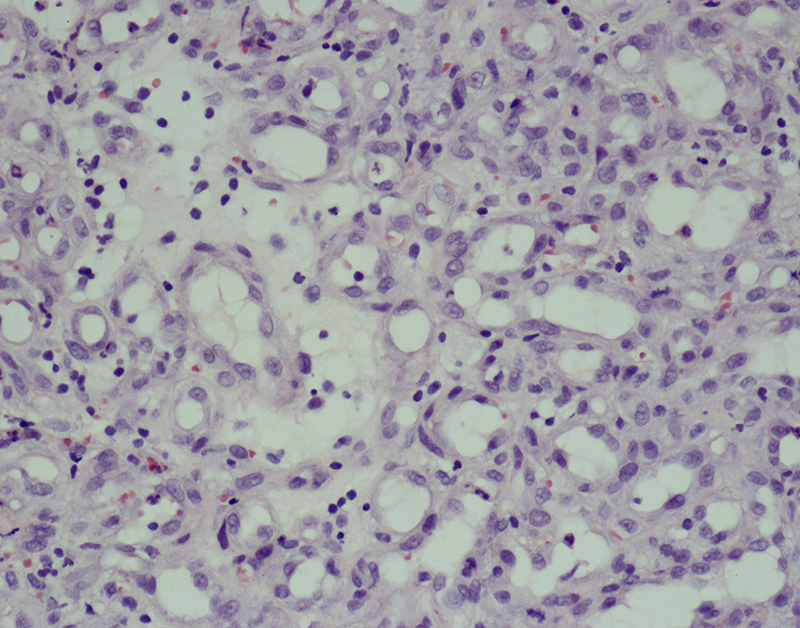

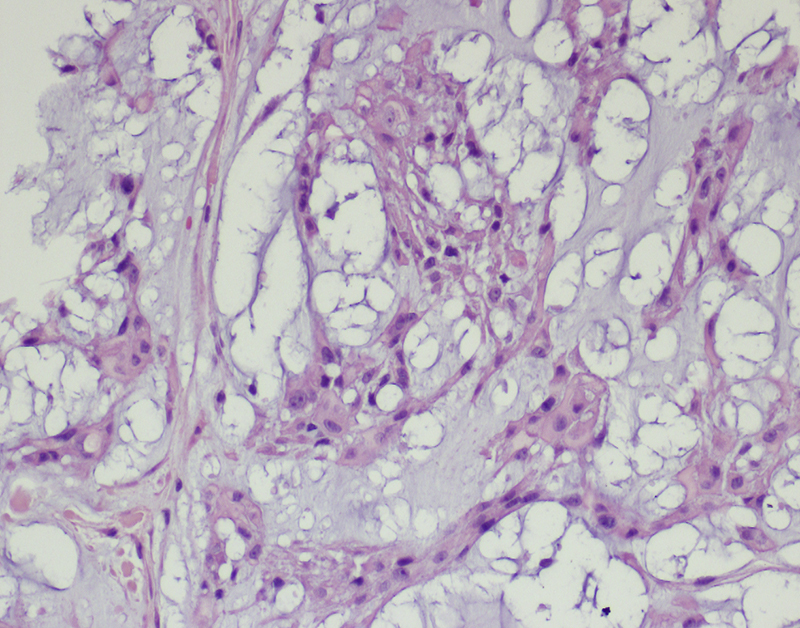

Morphologic picture: Macroscopically, benign tumors are well circumscribed and encapsulated. According to the fat content, they are yellow, gray-white or pale-pink and are sometimes myxoid. On microscopic examination, well-differentiated mature adipocytes are found. In other cases fibroblast-like spindle cells can be found (Fig. 5). By definition, lipoblasts are not found in benign cases. The presence of lipoblasts is an indication of malignancy and the appropriate diagnosis is liposarcoma.

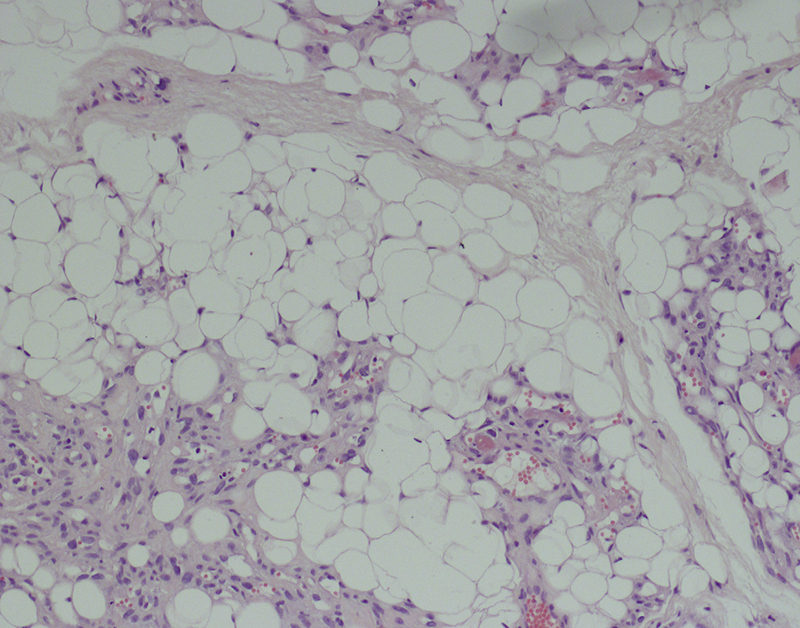

Fig. 5.

Lipomas are characterized by the presence of mature adipocytes. As it is a soft tissue tumor, cells differentiating into benign fibroblasts can also be seen. Hematoxylin and eosin staining, primary objective magnification 10×.

Other important notes: Some lipomas carry the translocation t (12q, 13–15).

Differential diagnosis: In benign tumors the diagnosis is easy, based on the presence of well-developed and mature adipocytes. In cases of poorly differentiated liposarcomas, the differential diagnosis includes all other poorly differentiated mesenchymal tumors such as fibrosarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, rhadomyosarcoma and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, as they might present a similar histologic pattern. For liposarcoma the key diagnostic feature is the presence of lipoblasts together with MDM2 and CKD4 positivity on immunostaining.18, 23, 24

4.3. Chondroma

Definition: A benign tumor of mesenchymal origin with differentiation toward cartilage.

Epidemiology: Benign (primary) chondromas in skull bases are extremely rare entities.

Morphologic picture: Benign-looking chondrocytes arranged in nests and surrounded by connective tissue.

Other important notes: There have been case reports of multiple chondromas in the skull base area, developing from syndromes of chondromatosis.

Differential diagnosis: In some cases, differential diagnosis with low-grade chondrosarcoma can be difficult. Correlation with radiologic features should be helpful.

4.4. Chondrosarcoma

Definition: Malignant soft tissue tumor, which is the third most common primary bone tumor (after osteosarcoma and plasmocytoma). Primary tumors in the head and neck area are rare, although they represent around 10% of all cases of chondrosarcoma. Such tumors may develop from the skull base, the nasal septum, or the gnathic bones.

Epidemiology: There are two peaks of incidence. The first of these occurs in young adults, around the 2nd or 3rd decade (this is the so-called mesenchymal type), while the other one occurs after 40 years of age.

Morphologic picture: Macroscopically, tumors are light blue to pearly-white and translucent. A lobular configuration occurs in low-grade tumors. In high-grade tumors, areas of necrosis and hemorrhage are usually visible. Microscopically, as a main component of the tumor formation, hyaline cartilage is seen. Cytologically, the tumor cells range from rather uniform round chondrocytes to spindle or clear cells, or dedifferentiated variants. There can be variable production of extracellular matrix, including cases with an extensive myxoid component (Fig. 6a and b). There may also be visible bone destruction, locally.1, 20

Fig. 6.

(a) Chondrosarcomas are composed of cells with varying levels of differentiation toward chondrocytes. For diagnostic purposes, chondroid matrix production is an important feature. Hematoxylin and eosin staining, primary objective magnification 10×. (b) Immuhistochemical evaluation of the expression of the proliferation marker, Ki-67. In this case, focally, up to 10% of cells are positive (meaning that 10% of cells are in a cell cycle phase other than G0). Primary objective magnification 20×.

Other important notes: There are reports of primary chondrosarcomas developing as primary lesions of the larynx or as a component of salivary carcinomas. The benign counterpart, namely chondroma, is very rare in the head and neck area.

Differential diagnosis: Differential diagnosis with other high-grade mesenchymal tumors such as osteosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, and liposarcoma should be considered in the case of dedifferentiated tumors. In such cases, morphologic features should be combined with the results of immunohistochemical studies. For differentiation with osteosarcoma, the presence of bone formation by neoplastic cells of the latter tumor is a crucial feature, but might require the review of multiple tumor samples. Differentiation with rhabdomyosarcoma can be based on the presence of desmin, myoD1 or Myf4 antigens that are consistent with muscle differentiation. This can be done by immunohistochemistry. Fibrosarcoma, in contrast to chondrosarcoma, is S-100 negative and, in histochemical stains, presents a reticulin positive rim around each cell. Poorly differentiated chondrosarcoma could be discriminated from liposarcoma by the presence of MDM2 and/or CDK4, which are typical for the latter.25, 26

4.5. Rhabdomyosarcoma

Definition: A malignant tumor of the so-called soft tissues (of mesenchymal origin), with skeletal muscle differentiation.

Epidemiology: In the nasopharyngeal localization, these tumors usually develop before the age of 20, with male predominance.

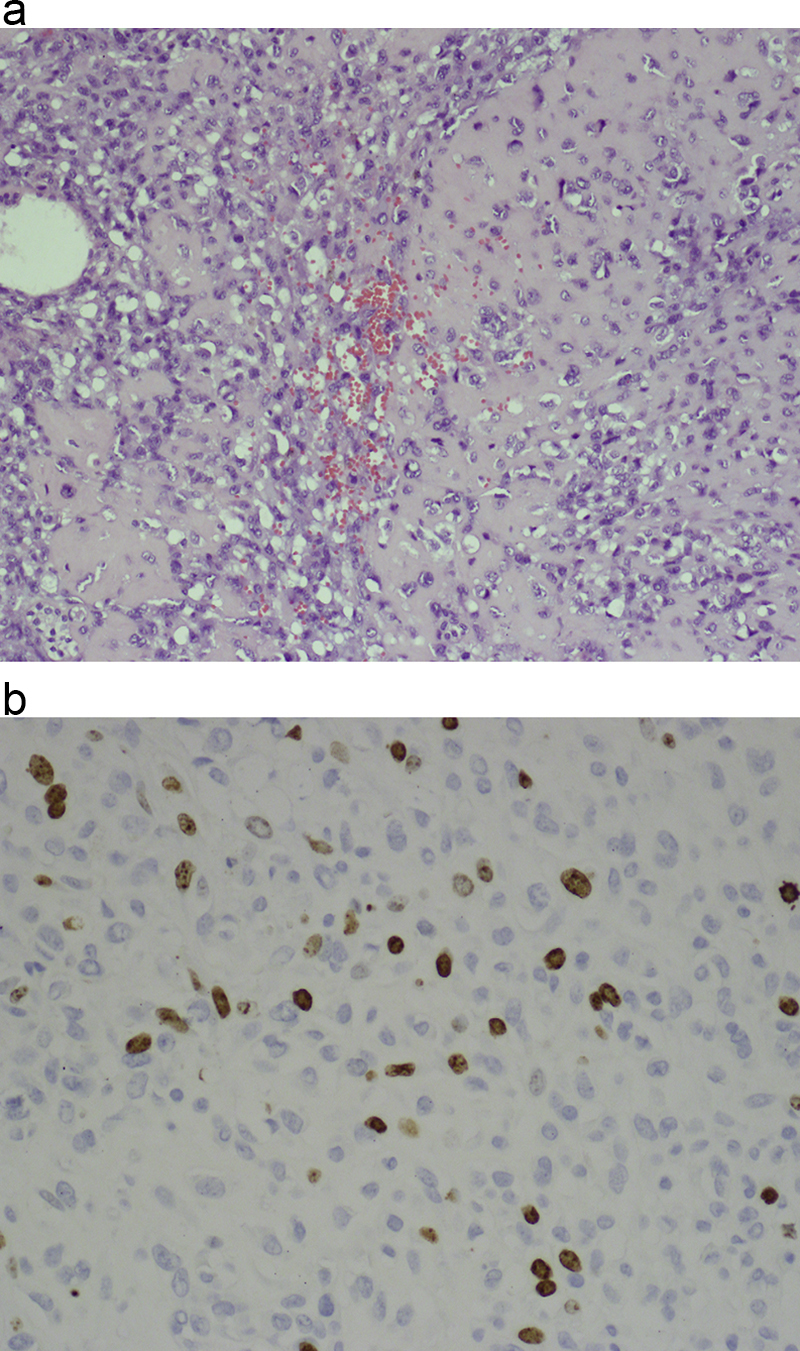

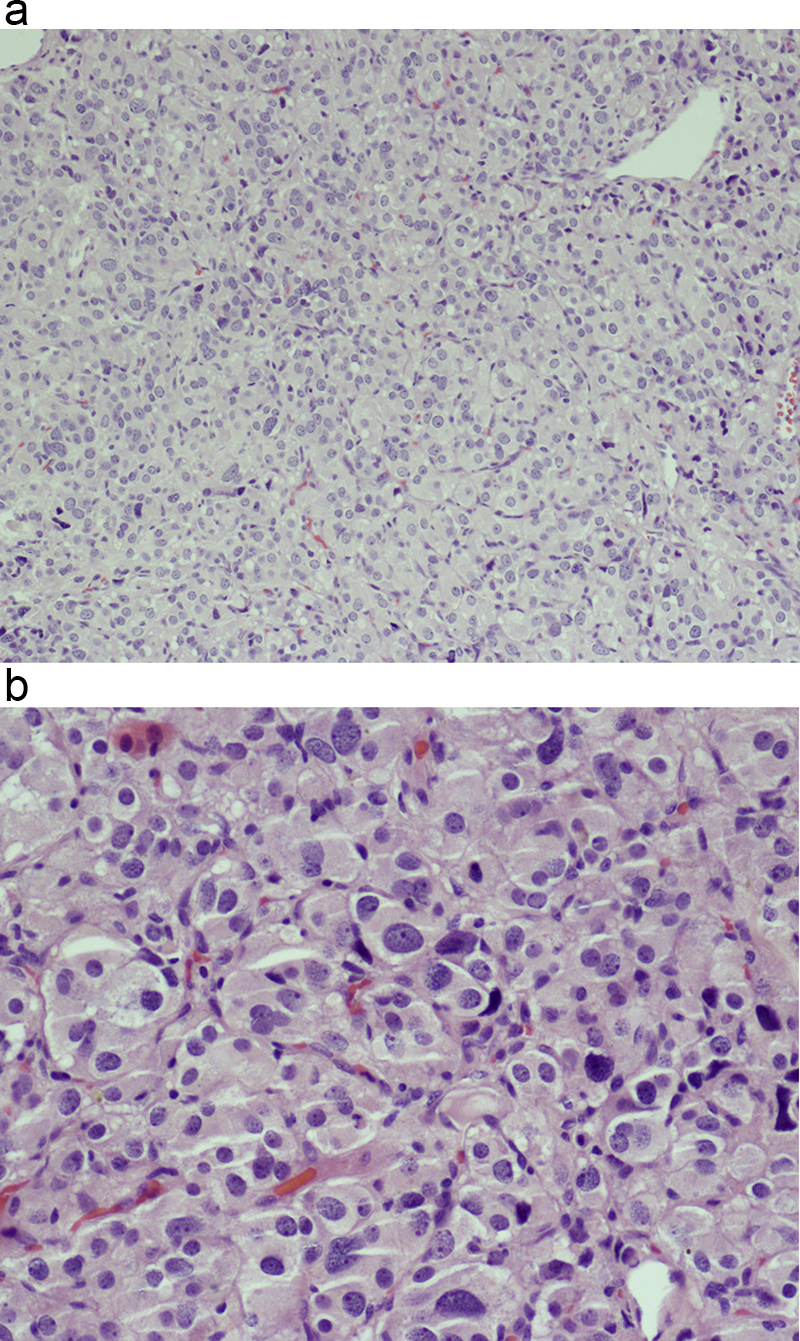

Morphologic picture: The tumor masses may have adestructive impact on surrounding structures. Microscopic examination allows the differentiation of three variants, namely: embryonal, alveolar and pleomorphic (that do not usually occur in the head and neck area). Regardless of subtype, the key diagnostic feature is an indication of skeletal muscle differentiation. It can be done by identification of muscle striatations (by either light or electron microscopy; in the latter, the presence of thin and thick filaments may be used as a minimal diagnostic criterion) or by immunohistochemistry; by confirmation of the expression of desmin, myoglobin, myogenin, MyoD1, Myf3, Myf4 and SMA. In the embryonal subtype, the tumor cells may be round to spindle shaped, with a primitive mesenchymal appearance (Fig. 7a–c). The cell nuclei are hyperchromatic. In the alveolar subtype, typically loosely cohesive primitive rhabdomyoblasts are surrounded by fibrous septa.

Fig. 7.

(a) In this case of rhabdomyosarcoma, differentiation toward skeletal muscle is visible in a part of the tumor. There is also a great variety of tumor cell shapes. Hematoxylin and eosin staining, primary objective magnification 20×. (b and C) Muscle differentiation was confirmed by immunohistochemistry tests for the presence of desmin (micrograph b) and the Myf4 marker (micrograph c). In both micrographs, primary objective magnification 20×.

Other important notes: In some centers, for diagnostic purposes, the presence of the FKHR gene mutation and fusion with PAX3 or PAX7 is used for confirmation of alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma.1, 18, 20

Differential diagnosis: As the cell of origin is the rhabdomyoblast, a diagnostic feature is the presence of cross-striations, but these are rarely visible at the histologic level (it is much easier to see them on ultrastructural studies). Some cases present as polypoid masses protruding from ear, and they should differentiated from aural polyps. In rhabdomyosarcoma of the botryoid subtype (itself a subtype of embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma), lying beneath the epithelium, there is a cambium layer with rhabdomyoblasts whose presence may be confirmed by the aforementioned immunohistochemistry tests. As rhabdomyosarcoma belongs to the group of so-called small blue cell tumors, it should be differentiated from lymphoma (atypical lymphocytes can be identified by T or B cell markers), melanoma (which should react with some of the following markers: S100, melanosome, melan-A) and from the Ewing sarcoma family of tumors (these lack myogenic markers but show strong cell membrane immunoreactivity for CD99, Fli-1).6, 18, 27

5. Central peripheral nervous systems originating tumors

5.1. Tumors of neuroepithelial origin

Such tumors are normally within the scope of neuropathology, but sometimes invade the skull base. In the following section selected tumors will be briefly introduced.11, 28, 29

5.2. Glial tumors

Definition: A group of tumors of glial differentiation. Recognized are such entities as: astrocytic neoplasms (including the most malignant glioblastoma), ependymomas, and oligodendrogliomas.

Epidemiology: As this is a complex group some details will be presented in the following section while morphologic variants will be displayed.

Morphologic picture: According to the present classification, the largest group consists of diffusely infiltrating astrocytomas. This group, according the cytologic appearance, can be further divided into fibrillary, gemistocytic and protoplasmic variants. The most common primary neoplasm of the brain is fibrillary astrocytoma with the main localization in white mater of hemispheres (in adults). Other sites observed include, in decreasing order of incidence, cerebellum, brain stem, and spinal cord. They are most frequently diagnosed in the 4th to 6th decades of life.

Macroscopically, these tumors present with diffuse expansion and blurring or effacement of gray-white matter. Usually, neither hemorrhage nor necrosis is found. Microscopically, a discohesive cellular infiltrate in a patternless array is found, with only slight hyperchromasia of the nuclei. Nuclei are typically round or oval and with a vesicular quality. There are no nucleoli. Sometimes microcystic changes are observed.

There are also other types of astrocytomas, such as protoplasmic astrocytoma (occurring more commonly in the gray matter), pilocytic juvenile astrocytoma (so named as they are typically present in childhood, adolescence or early adult life; with a predilection for the cerebellum and the third ventricle region, they have a typically biphasic cellular presentation, namely fascicular and microcystic array), pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma (alarming as it looks, using only histological criteria, it is a relatively indolent tumor; typically present in adolescence and in early adult life. It is a well-demarcated tumor, most commonly located in the temporal lobes), subependymal giant cell astrocytoma (typically in the 1st or 2nd decade of life, and is associated with tuberous sclerosis – Bourneville's disease), and desmoplastic cerebral astrocytoma of infancy (which grows in the first year of life, manifesting with increased intracranial pressure). Also diagnosed are mixed gliomas, which present elements suggesting differentiation along more than one of the cell lines described above.28, 30

In anaplastic astrocytoma (female predominance, peak incidence in 5th decade), grade III according to WHO four-grade malignancy classification and which in most cases evolves from well-differentiated precursors, typical microscopic findings include: nuclear angulation, variations in contour and dimension, and dense hyperchromasia. In contrast to the entities above, mitotic figures and increased vascular blood supply are observed.

The most malignant entity in this group is glioblastoma, also called glioblastoma multiforme (WHO grade IV) which may develop as a “primary” or as a “secondary” tumor. The former occurs de novo, which means that there was no demonstrable precursor lesion. The latter is attributed to cases showing malignant transformation of a benign lesion. Epidemiological studies indicate that this tumor accounts for about 10–15% of brain tumors of adults.

Macroscopically, these tumors are presented as relatively well circumscribed (a peculiar feature of central nervous system malignancies; in other localizations, the majority of malignant tumors have poorly defined borders). Hemorrhagic and necrotic areas are very common. Histologically, it is a highly cellular and pleomorphic tumor with extreme variation in cytologic features. There are well-differentiated elements/cells which can be intermingled with bizarre multinucleated giant, spindle, epithelioid, rhabdoid, small or signet-ring tumor cells. Mitoses are numerous. Proliferating blood vessels (used by some pathologists as a hallmark of the tumor) may be present as glomeruloid or solid tufts.18, 28

Oligodendrogliomas constitute about 5–15% of gliomas. They are most common in the 4th–5th decade of life and develop mainly within white matter of the hemispheres (frontotemporal or parietal lobes location). Macroscopically, they are well-demarcated masses of soft, grayish-pink tissue, usually in the subcortical white matter. Cystic changes are common. In the classic presentation, microscopic examination shows a sheet-like or permeative proliferation of uniform, round nuclei surrounded by optically clear halos. Perineuronal aggregation (satellitosis) is seen. When mitotic activity is present and foci of coagulative necrosis and dense cellularity are found, they are features of anaplastic oligodendroglioma.

Ependymomas are the least common (4–6% of all CNS primary tumors) in this group. In children, they usually occur as intracranial tumors, and as intramedullary lesions in adults. About 75% of lesions in children are infratentorial (IV ventricle) and cause increased intracranial pressure secondary to obstructive hydrocephalus. Macroscopically, they have grayish or white coloration and a granular texture, friable consistency, lobulated contours and remarkable circumscription (being better demarcated than astrocytomas). On microscopic examination, the most common form is the cellular variant. In this tumor perivascular pseudorosettes and dystrophic calcifications are found (sometimes with osseous or chondroid metaplasia). The anaplastic (malignant) ependymoma is characterized by cellular density, mitoses, increased pleomorphism with vascular proliferation, and the presence of necrosis.

Other important notes: For fibrillary astrocytoma, risk factors include: irradiation, type 1 neurofibromatosis, Turcot's syndrome (colonic polyposis), and HIV-1 infections. As some authors suggest tumor biology depends in part on p53 and retinoblastoma gene expression.1, 28

Differential diagnosis: The glial origin of cells could be confirmed by the presence of GFAP immunoreactivity (with differing proportions of positive cells depending on the specific subtype). Subsequently, diffuse fibrillary astrocytoma could be differentiated from gliosis (a reactive change) by the presence of hypertrophy, but not hyperplasia, of glial cells in the latter lesion. Glioblastoma could be differentiated with lymphoma or metastatic carcinoma through the presence of small cells, but in all histologically questionable cases, immunostaining for GFAP and hematopoietic markers or cytokeratins should be helpful. Some cases of ependymoma could mimic glioma, but the former is characterized by the presence of true rosette formation by neoplastic cells as well as by intracytoplasmic microvilli lined lumina (visible at the ultrastructural level). Oligodendrogliomas that show clear cells should not be confused with clear cell meningiomas or with clear cell ependymoma or metastatic clear cell carcinoma. In such cases as these, additional immunostaining is crucial.20, 28

5.3. Esthesioneuroblastoma

Definition: In the WHO classification, this neoplasm is currently named as olfactory neuroblastoma. It is a malignant tumor derived from the olfactory membrane of the sinonasal cavity. It is a rare and malignant tumor occurring only in this localization.

Epidemiology: It might occur from childhood to late adulthood with peak prevalence around 50 years of age.

Morphologic picture: Macroscopically, these usually form large, highly vascularized, polypoid structures. The lesion usually develops in the submucosa and is covered by normal mucosa. The size varies from small to large lesions with invasion of the paranasal sinuses and orbit. On microscopic examination, nests or lobules of uniform small cells are present, with inconspicuous nucleoli in “salt and pepper” nuclei, without pleomorphism. Groups of cells are separated by fibrous stroma. The cytoplasm of such cells is usually scanty. Necrosis is usually absent. As it has a neural origin, one third of cases also show Homer-Wright pseudorosettes as well as Flexner–Wintersteiner rosettes. In immunohistochemical studies, consistent expression of NSE is seen, together with synaptophysin and neurofilament positivity in the majority of cases. Positivity for GFAP and chromogranin has also been reported. S-100 is positive only in sustentacular cells that form a thin rim around the tumor cell lobules. Markers such as EMA, cytokeratins, CEA, CD99 and HMB45 are absent in the case of esthesioneuroblastoma.31, 32

Other important notes: The name is not associated with neuroblastomas occurring in other localizations.

Differential diagnosis: As the tumor is composed of small round “blue” cells, it should be differentiated from other lesions with the same microscopic appearance. Such tumors may include lymphoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, malignant melanoma, neuroendocrine carcinoma or sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma. In almost all cases the proper diagnosis should be made after immunohistochemistry. Lymphoma may be excluded after stains for leukocyte antigens while malignant melanoma is positive for HMB-45 and/or melan-A. In the case of rhadomyosarcoma, muscle differentiation markers (myoD1, Myf4, desmin) are key elements, while in the case of carcinomas, both neuroendocrine and undifferentiated, at least some of the cytokeratins should be demonstrable.33

5.4. Choroid plexus papilloma

Definition: A benign tumor that recapitulates the structure of choroid plexus.

Epidemiology: Almost all occur in children below 10 years of age.

Morphologic picture: Macroscopically, the tumor is lobulated. Microscopically, it resembles normal choroid plexus. It is usually composed of one layer of epithelial cells which may be pigmented, oncocytic, osteogenic or mucus-secreting, with mild atypia, and overlying a fibrovascular core.

Other important notes: All choroid plexus tumors are very rare. They constitute below 0.5% of all intracranial tumors. Up to 30% of these tumors might undergo malignant transformation. Some examples of this tumor are found in Li-Fraumeni syndrome and Aicardi syndrome.

Differential diagnosis: Some tumors might resemble ependymoma (myxopapillary subtype) but such tumors occur in different locations. Yet another differential diagnosis is papillary meningioma, but typical cell whorls of meningothelial cells can be recognized in such tumors during a detailed microscopic examination.20, 28

5.5. Meningioma

Definition: A benign tumor composed of meningothelial cells.

Epidemiology: Meningioma belongs to one of the most common primary intracranial lesions. It occurs most commonly in mid adult life. Women are much more commonly affected (especially those with breast tumors), which is attributed to the presence of receptors for progesterone.

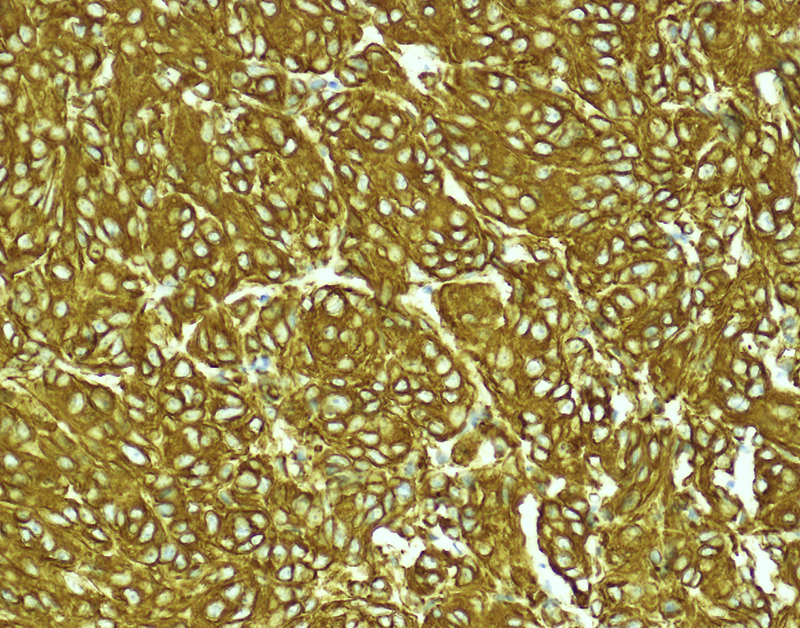

Morphologic picture: Macroscopically, it is a solid lobulated mass, broadly anchored to the dura matter. In some cases this tumor may permeate the neighboring skull structures, provoking a highly characteristic form of osteoplastic expansion (hyperostosis). On cross-section, meningiomas are usually grayish-tan and soft (but highly collagenized examples are also found). Calcification is rarely apparent on gross examination. Microscopically, so-called meningothelial cells are observed, with delicate round or oval nucleoli and inconspicuous nucleoli. The cytoplasm is lightly eosinophilic and cytoplasmic borders are indistinct. Commonly, tumor cells are concentrically wrapped in tight whorls (Fig. 8), with pale nuclear “pseudo-inclusions” consisting of invaginated cytoplasm. Lamellated calcospherules, known as psammoma bodies, are also found. According to the WHO classification, meningiomas are graded from 1 to 3. The grade 1 group consists of nine subtypes (menigothelial, fibrous/fibroblastic, transitional/mixed, psammomatous, angiomatous, microcystic, secretory, lymphoplasmocytic and metaplastic), three subtypes fall into the grade 2 category (chordoid, clear cell and atypical) and further three subtypes are in grade 3 (papillary, rhabdoid and anaplastic). Arachnoid cap cells (so called meningothelial cells) have been identified as the origin of menigiomas. In immunohistochemical studies they were found to be positive for EMA, CK18, CEA, claudin 1 (in up to 50% of cases) and negative for CK20, vimentin (in some cases), S-100 (except in fibrous meningioma) and GFAP.11, 34

Fig. 8.

Whorls of meningothelial cells are present. In this micrograph the tumor cells are highlighted by immunohistochemical staining for vimentin. Primary objective magnification 20×.

Other important notes: Multifocal meningiomas are typically found in cases of type 2 neurofibromatosis. Other risk factors include ionizing irradiation and trauma. Most meningiomas develop within the cranial cavity and are dura mater based, being found in the vicinity of the superior sagittal sinus.

Differential diagnosis: In cases with predominant spindle cells, the main differentials include: schwannoma, hemangiopericytoma and solitary fibrous tumors, all of which are negative for claudin-1. Additional staining could be helpful, S100, for example, is positive in schwannomas, CD34 is positive in solitary fibrous tumors and in hemangiopericytomas. Some of the above markers may be positive in specific subtypes of meningioma, however.11, 31, 34

5.6. Neurilemmoma

Definition: A benign tumor composed of differentiated neoplastic Schwann cells (also called Schwannoma).

Epidemiology: This is the most common tumor of the peripheral nerve, comprising about 8% of all intracranial tumors (with 80–90% of the cerebellopontine angle). Peak incidence is in the 3rd through 6th decades of life. For those arising within the skull, there is a predilection for the sensory nerves (especially for nerve VIII). Those arising in extradural locations have a predilection for the mixed motor and sensory nerves.

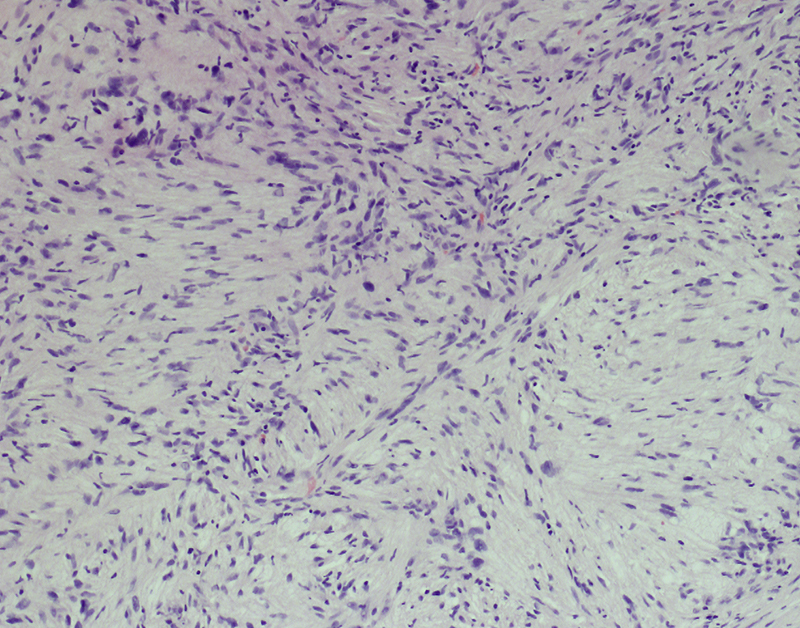

Morphologic picture: The majority of these tumors are solitary and discrete. Macroscopically, these are firm, encapsulated, tan and translucent, often yellow (in cases with xanthomatous degeneration) or red in color (when hemorrhage develops). They grow centrifugally with compression of the surrounding tissues but without infiltration. Microscopically, they are comprised of uniform cells of the Schwann cell phenotype, which are spindle shaped, with pale cytoplasm that merges with adjacent collagen bundles. The nuclei are elongated. In some cases the cells may be aligned parallel to the interwoven fascicles. A compact configuration known as Antoni A, together with an areolar or myxomatous appearance, known as Antoni B (Fig. 9) may also form. The palisading tumor cells’ nuclei, arranged in a pattern resembling piles in a fence with an intermediary anuclear zone, constitute the hallmark known as Verocay bodies. Areas of degeneration, even with cellular pleomorphism, are sometimes found in older lesions. In some cases a few mitoses may be observed.

Fig. 9.

Elongated cells, singly interwoven or arranged in fascicles, are distributed within a partially myxomatous stroma. In this micrograph, the Antoni B subtype is presented. Hematoxylin and eosin staining, primary objective magnification 10×.

Other important notes: This tumor is sometimes named Schwannoma. In type 2 neurofibromatosis (in which a mutation on the NF2 gene of chromosome 22q causes the production of a gene product called: schwannomin) lesions can be bilateral with multiple meningiomas.

Differential diagnosis: As the tumor is composed of spindle cells, sometimes in fascicles, it should be differentiated from fibromas, which are S100 negative and CD34 positive, and from meningiomas, which are S100 positive but also EMA positive. The latter entity is also composed of menigothelial cells, which have a characteristic appearance. The differentiation with neurofibroma is of some interest, as both neurilemmoma and neurofibroma are S100 positive. CD34 positivity is stronger, however, in a fibroblastic admixture of the former tumor. Differentiation with malignant peripheral sheath tumors is mainly based on the degree of cellular pleomorphism, the presence of necrosis and a high mitotic rate. The infiltrative growth pattern is also typical for a malignant tumor.1, 20

5.7. Paraganglioma

Definition: A tumor developed from the paraganglia outside the adrenals. They develop along the structures of the paravertebral sympathetic and parasympathetic chains.

Epidemiology: These are rare tumors, occurring mainly in the 5th and 6th decade, with a twofold female predominance.

Morphologic picture: Tumors range from small up to more than 10 cm in diameter. Macroscopically, they are well circumscribed and encapsulated by fibrous tissue. Microscopically, the most characteristic features are zellballen, arrangements of variously sized nests of tumor cells (Fig. 10a and b) surrounded by fibrotic septa. The main types of cells vary in appearance, from those with finely-granular cytoplasm to deeply basophilic ones. There are cases with clear cells as well. The nuclei are also rather pleomorphic with some being small and round while others are large or even vesicular. The second cell type present, which is typically S100 positive, are sustentacular cells that surround the aforementioned nests of cells.

Fig. 10.

(a) Palish cells of paraganglioma, with polygonal cytoplasm contours, are gathered in small groups. Hematoxylin and eosin staining, primary objective magnification 10×. (b) On close microscopic view, the characteristic appearance of zellballen is clearly visible. The cell nests are surrounded by a thin rim of so-called sustentacular cells. Hematoxylin and eosin staining, primary objective magnification 20×.

Other important notes: The immunohistochemical profile of these tumors reflects their neuroendocrine origin, with positive reactions for chromogranin, synaptophysin, CD56, NSE, leu7, S100 and even somatostatin or calcitonin.

Differential diagnosis: In cases without the zellbalen pattern, paragangliomas usually require differentiation from neurilemmoma/schwannoma (which are S100 positive whilst being synaptophysin and chromogranin negative) and meningioma which is EMA positive but negative for neurosecretory markers.18, 35, 36

6. Hematopoietic tumors

6.1. Lymphomas (from mucosa of the nose, sinuses)

Definition: Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue tumors, most commonly occur in the nasal cavity and sinuses. The most common entities in this localization include lymphomas of NK/T cells, diffuse large B cells, peripheral T cells, or mantle cells.

Epidemiology: Tumors of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses lymphomas, as a group, are the second most common primary malignancy of the skull base. Extranodal NK-/T-cell lymphoma of the nasal type occurs more commonly in Asia and South America and is rare in the Western world. Its peak incidence is in the 6th decade with male predominance. The most common B-cell lymphoma, namely diffuse B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), occurs in the tonsils (70% of cases, and with decreasing incidence in the nasopharynx and base of tongue) in patients in their 6th through 8th decade of live with male predominance.

Morphologic picture: As this is a broad group of tumors, specific descriptions of these entities have been presented elsewhere.

Other important notes: It is worth remembering that, for proper diagnosis of primary lymphomas in this localization, clinical data combined with laboratory results and pathologic studies are required. For this diagnosis a large panel of immunohistochemical tests (for the evaluation of CD and other markers) is obligatory. A full description of lymphoma diagnosis is beyond the scope of this paper and details can be found elsewhere.

Differential diagnosis: Usually includes other small round cell tumors such as poorly differentiated carcinoma, malignant melanoma, or mesenchymal tumors, such as rhadomyosarcoma. Features typical of the aforementioned entities have been already presented above.1, 37

6.2. Plasmocytoma

Definition: A tumor of hematopoietic origin, characterized by the monoclonal growth of plasma cells.

Epidemiology: The pharynx belongs to one of the most common localizations for primary plasmocytomas outside the bone marrow. The peak incidence is around 60 years of age.

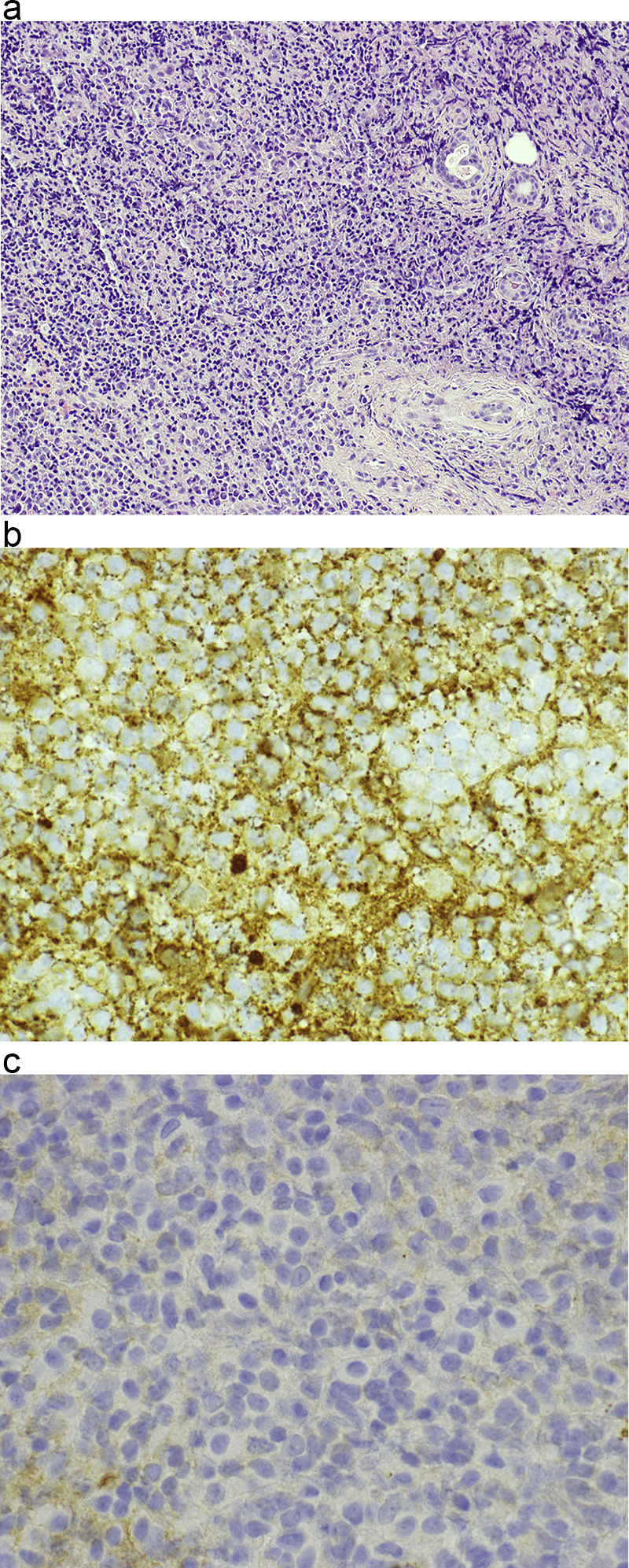

Morphologic picture: The tumor is usually a lobulated mass of an infiltrative nature. The tumor is normally composed of a monotonous population of normal or almost normal looking plasma cells (Fig. 11a–c). For the proper diagnosis, the use of immunohistochemistry is required to reveal restriction of light chain production (kappa or lambda). Other commonly used markers include CD138 or CD38 (markers of plasma differentiation). Interestingly, as with normal plasma cells, they are negative for the B cell/lymphocyte marker CD20, despite being derived from B cells.

Fig. 11.

(a) In this case of hard palate plasmocytoma, a dense cellular infiltrate of monomorphic cells of plasmocytoid appearance is visible. Hematoxylin and eosin staining, primary objective magnification 10×. (b and c) By immunohistochemical studies, light chain production restriction was confirmed. In micrograph (b) positive cytoplasmic expression of kappa light chains in the tumor cells can be seen. In micrograph (c) no expression of lambda light chains is observed in the neoplasm. In both micrographs, primary objective magnification 40×.

Other important notes: Extramedullary plasmocytomas account for only about 10% of cases with solitary lesions. Thus, whenever a diagnosis is made, the presence of other such lesions following the course of multiple myeloma in other localizations, such as in intramedullary bone, should be carefully excluded.

Differential diagnosis: The obvious plasma cell or plasmocytoid appearance includes cells with an eccentrically placed nucleus, and Dutcher bodies (accumulation of abnormal immunoglobulins) in the cytoplasm. However, immunohistochemical confirmation of the expression of CD38 or CD138, with restriction to one of the light immunoglobulin chains, kappa or lambda, is crucial for diagnosis.20, 38, 39

7. Miscellaneous or composed origin tumors

7.1. Tumors of the pituitary gland

From the clinical point of view, these tumors are worthy of note because of the possible excess production of hormones and because of headaches and problems with vision as a result of the tumor mass compressing the surrounding structures. A functional approach to the pituitary gland divides it into the anterior and posterior pituitary. In the former, responsible for hormone production, we might encounter the development of adenoma, carcinoma or oncocytoma. In the latter, as it is formed by evagination of the central nervous system, such tumors as gangliocytoma or astrocytoma might be anticipated. Epidemiologically, anterior pituitary tumors are more common, and the following descriptions will focus on some examples. One of the first classifications was based on the histological criterion of staining patterns of the acidophilic, basophilic and chromophobic cells from which the lesion was built. However, as there was no correlation with the clinical course, it is now of historical value only. Introduction of methods for the evaluation of cell content (such as immunohistochemistry for prolactin, growth hormone and ACTH), together with the ability to assess their levels in the peripheral blood, have allowed a new approach to the division of these tumors into hormonally active (vast majority) or inactive. However, morphology is almost uncorrelated with the biology and clinical presentation of these tumors, except that larger tumors, greater than 1.0 cm, the so-called macroadenomas, have a greater tendency for infiltrative growth and recurrence. The following is a brief description of some of them.

The most common tumor of the anterior pituitary is prolactinoma (or PRL-secreting tumor).28, 35, 40

Definition: A tumor developing in the pituitary gland and composed of prolactin producing cells.

Epidemiology: Prolactinoma is the most common primary pituitary lesion, accounting for about half of all pituitary adenomas and about 80% of functioning cases. It usually develops between the 3rd and 5th decade of life.

Morphologic picture: Macroscopically, these tumors form soft, well-circumscribed nodules that may extend beyond the sella turcica. About one-third show infiltrative growth, which may be regarded as a feature of malignancy. Histologically, the majority of these tumors are composed of monomorphic cells, typically of the chromophobic or acidophilic types, with uniform round nuclei, in which delicate, stippled chromatin may be observed. The nucleoli are inconspicuous. The cytoplasm is of moderate quantity. In one fifth of cases, microcalcifications or small hyaline bodies can be found.

7.2. Growth hormone secreting adenoma

Definition: A tumor developing in the pituitary gland, which is composed of growth hormone producing cells.

Epidemiology: These tumors comprise about one-fifth of primary pituitary adenomas. Clinical presentation depends on the age of hormonal tumor activity. Gigantism develops in cases where the tumor develops before epiphyseal closure of the long bones (children and adolescent patients). In adult patients, usually in their forties, acromegaly develops.

Morphologic picture: In the majority of cases the cells are acidophilic or chromophobic with granular cytoplasm. Nuclei with prominent nucleoli are typical. In this group of tumors, slight nuclear pleomorphism, as well some multinucleate cells are found. Fibrous bodies are a peculiar marker of this tumor and are formed by the accumulation or aggregation of intermediate filaments that react positively with cytokeratins when immunostaining is performed.

7.3. Adenoma secreting ACTH

Definition: A tumor developing in the pituitary gland, which is formed by the overgrowth of ACTH producing cells.

Epidemiology: Usually develops during the 4th decade of life. These tumors are 8 times more common in females than males. Cushing's syndrome is the classical clinical presentation.

Morphologic picture: This tumor type is usually composed of basophilic cells with very granular cytoplasm. In some cases, hyaline material may be seen surrounding cells, resulting in a “target-cell” appearance. Papillary cellular formations are also visible.

7.4. Null-cell adenoma

Definition: A tumor developing in the pituitary gland which shows neither clinical nor immunohistochemical evidence of hormone production.

Epidemiology: Usually develop in elderly patients.

Morphologic picture: In the majority of cases, tumors measure over 1.0 cm in diameter (macroadenoma). The histological picture most commonly presents chromophobic cells arranged in diffuse patterns.2, 15, 35

7.5. Pituitary carcinoma

Definition: A tumor developing in the pituitary gland, usually with hormonal activity, that produces systemic or craniospinal metastases.

Epidemiology: These tumors could occur at any age but typically in the 3rd–5th decade. There is an equal gender predilection.

Morphologic picture: No typical features of malignancy have been described. High expression of p53 has been found in immunohistochemical studies.

Differential diagnosis: As the histology of pituitary tumors has a minor impact on the diagnosis, differentiation between entities is based on the clinical course and on the hormone production status (either by laboratory tests or by immunohistochemistry).41

7.6. Malignant melanoma

Definition: A malignant tumor derived from melanocytic cells or their precursors. Primary tumors in the skull base, apart from those arising in the skin, usually develop in the mucosal membranes.

Epidemiology: Tumors usually develop in adults and primary sites are most commonly found in the oral or nasal cavities.

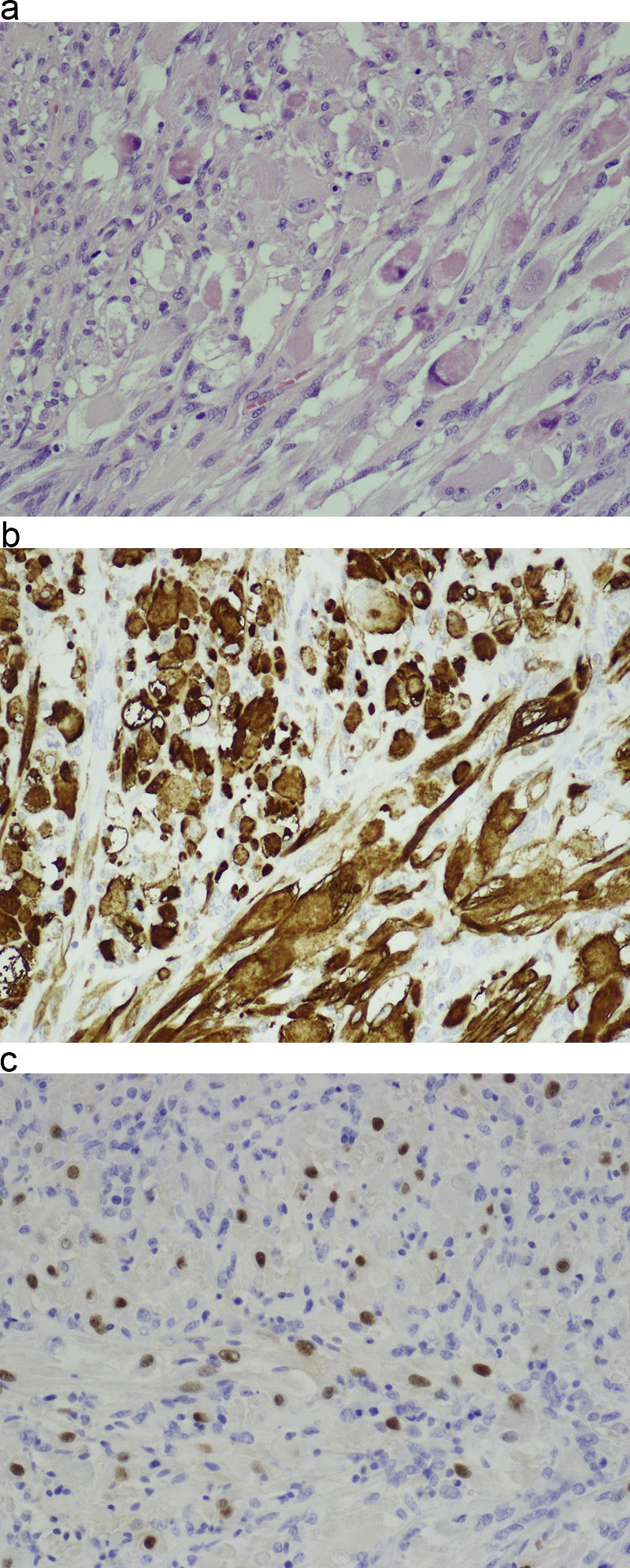

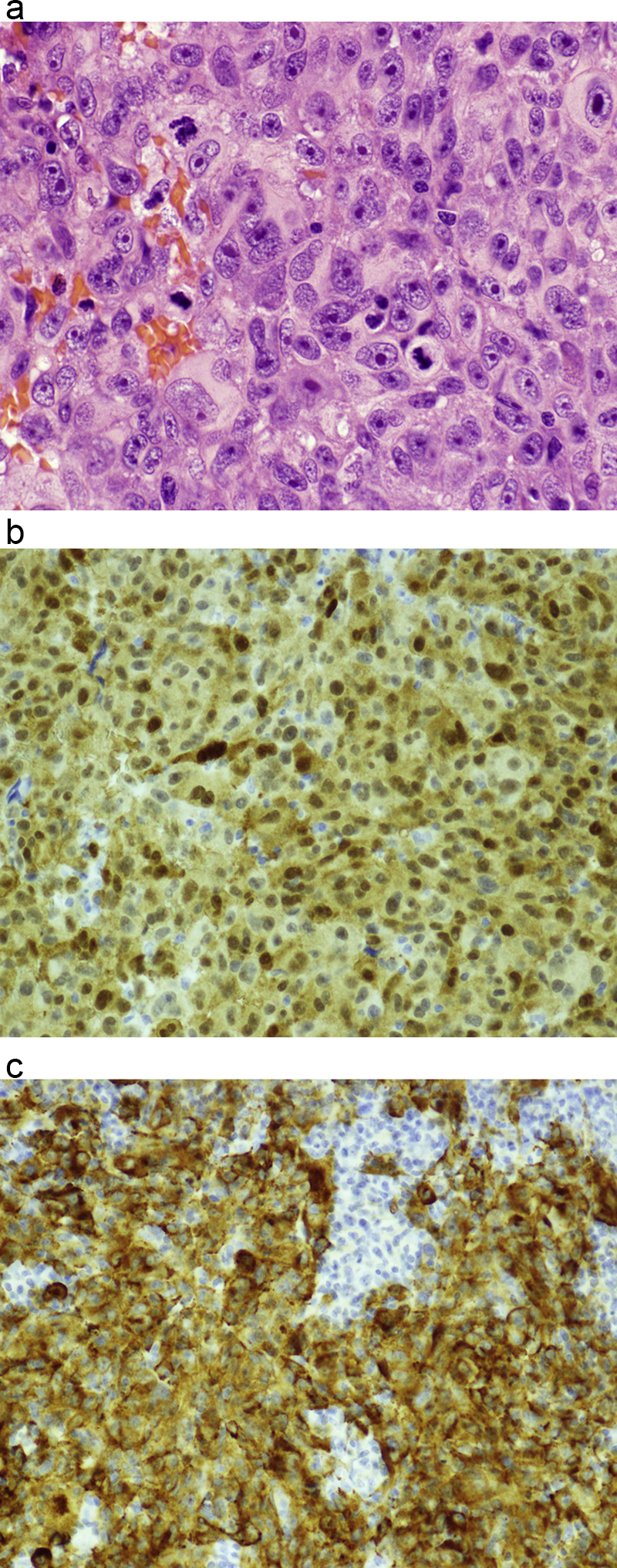

Morphologic picture: The tumor is composed of atypical melanocytes. Most commonly, there are sheets or islands of epitheliod melanocytes (Fig. 12a–c). The cells may be round, spindle shaped or polygonal, with a high mitotic rate.

Fig. 12.

(a) Malignant melanomas are typically composed of polygonal cells with high mitotic rates. Multiple mitoses are clearly visible. Hematoxylin and eosin staining, primary objective magnification 40×. (b) Immunohistochemical evaluation of S100 expression, the most consistent marker of melanoma. The tumor cells present strong expression. Primary objective magnification 20×. (c) Immunohistochemical expression of melan-A, a specific marker for melanoma. Primary objective magnification 20×.

Other important notes: The immunoprofile of melanocytes includes positive reactions to S100 (the most consistent marker of melanocytes, but least specific), HMB45, and melan-A.

Differential diagnosis: In the majority of cases, after a detailed microscopic search, melanin pigment can be found, its presence being regarded as diagnostic. However, clear cell melanoma should be differentiated from liposarcoma. For the former, expression of S100 and HMB45 are diagnostic, while S100, MDM2 and CDK4 are used for the latter. Hematopoietic tumors are distinguished by the presence of specific CD markers. Malignant tumors of mesenchymal origin, such as rhabdomyosarcoma or osteosarcoma, can be excluded because of the lack of melanin and melanocyte marker expression, along with the expression of differentiation markers.1, 6, 23

7.7. Teratoma

Definition: A tumor derived from germinal cells, with features of differentiation toward at least two of the three germ cells layers (namely, the ectoderm, mesoderm and endoderm).16, 42

Epidemiology: The majority of these tumors, that is almost 90%, are found during the 1st year of life. They are rarely diagnosed later.

Morphologic picture: Macroscopically, lesions may be solid or cystic. Histologically, they can be divided into mature (benign) and immature (malignant) lesions. The tissue composition of such tumors depends on the types of cells derived from the embryonic cell layers in a given case. Minimum differentiation is between epithelial components (squamous, glandular, cuboidal or respiratory epithelium) and mesenchymal tissues (bone, cartilage, muscles and fat). Organ level differentiation is recognized by the formation of near-normal parts of different organs; skin being the most common of them.

Other important notes: Teratomas of the skull base found in adults are usually malignant.

Differential diagnosis: As teratomas show differentiation toward various tissues, such mixed composition gives pathologic features that rarely raise diagnostic problems. The skull base is, however, an extremely rare location for such tumors, which are relatively common in the ovaries or testes.1, 23, 43

7.8. Chordoma

Definition: A malignant tumor, probably arising from remnants of the embryonal notochord.

Epidemiology: A rare bone tumor (accounting for less than 4% of malignant bone tumors), it may develop from childhood until old age, with peak prevalence in the 5th and 6th decades. Males and females are equally affected.

Morphologic picture: Macroscopically, these are lobulated masses with, on cross section, a myxoid and neural appearance. On microscopic examination, two cell types are recognized. Elongated “chief” cells with an epithelioid appearance, and large mucus-producing cells (Fig. 13). On immunohistochemical examination they exhibit positive reactions to: EMA, S100, HBME, and sometimes to keratins.

Fig. 13.

Chordoma is composed of elongated “chief” cells with an epithelioid appearance, and large mucus-producing cells. Hematoxylin and eosin staining. Primary objective magnification 10×.

Other important notes: Chordomas develop in 3 main localizations: sacrococcygeal (most common, two thirds of cases), sphenooccipital (about quarter of cases) and vertebral.

Differential diagnosis: The diagnosis is made according to the immunohistochemical profile, together with the presence of areas of hyaline-type chondroid tissue. In differential diagnosis, chondrosarcoma must be taken into account. The differentiation can be made based on localization, as chondromas do not usually grow in the middle line. On immunohistochemical studies, both chordoma and chondrosarcoma, are S100 positive, but the latter is EMA and keratin negative.1, 18, 44

8. Metastases

Secondary tumors developing in the area of the skull base are most commonly derived from the breast, lung, kidney, gastrointestinal tract or prostate. In most cases, they reproduce the morphology of the primary site tumors. For a precise diagnosis, relevant clinical data are needed. Metastases occur with the same age distribution (plus a delay for systemic spread) as with the primary lesions; thus, the peak incidence occurs between the 5th and 8th decade.1, 45

8.1. Final remarks

Skull base tumor biology is a rapidly expanding field that keeps providing new opportunities for exploration. Many results have come as a direct result of technological progress. At present, we know that tumors arise as a consequence of a series of molecular events that fundamentally alter the normal properties of cells. Altered cells are able to divide and grow in the presence of signals that would normally inhibit that growth. Heritable changes allow the tumor cell and its progeny to divide and grow, to spread and to invade other tissues.

Years ago, the Human Genome Project brought significant improvements to molecular biology and bioinformatics, with databases such as NCBI or OMIM. Currently, we can see the development of the next generation of such techniques, with deep sequencing and array-based methods ahead. Due to these incredible improvements, it is worth reviewing several molecular elements involved in skull-base tumor biology, based on modern bioinformatic tools and databases. Table 3 shows genes, chromosomal abnormalities and syndromes with a congenital background derived from several sources of biological information. While this only partially covers the requirements of clinical sciences, it may, nevertheless, initiate a new approach to diagnosis, including histological data and counseling procedures. The development of techniques in molecular biology, and the use of databases, may soon be useful in early diagnosis, long before tumors become visible.

Table 3.

The genetic abnormalities found in skull base tumors.

| Tumors | Involved genes | Known cytogenetic features | OMIM evidence of inheritance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adenoid cystic carcinoma | MYB, BCL2, ACCS, SNAI2, KIT | Not yet established | Not yet established |

| Cholesteatoma | DEFB4A, KRT13 | Not yet established | 604183 |

| Chondroma | SDHD, SERPINA3 | Multiple changes | Multiple syndromes |

| Chondrosarcoma | EXT1 | 8q24.11 | 215300 |

| Chordoma | CHDM | 7q33 | 215400 |

| Chorioid plexus papilloma | TP53 | 17p13.1 | 260500 |

| Craniopharyngioma | CTNNB1, BRAF, MMP9 | Multiple changes | Multiple syndromes |

| Esthesioneuroblastoma | EPOR | −3p, +17q | 133450 |

| Gliomas | IDH1, TP53, ERBB2 | 2q34, 17p13.1, 17q12 | 137800 |

| Hemangioma | KDR | 2p13.3, 4q12, 5q35.3 | 602089 |

| Lipoma | LPP, LHFPL5 | Multiple changes also found in liposarcomas | 151900 |

| Lymphomas (MALT-type, from mucosa of the nose, sinuses) | MALT1 | 18q21.32 | 604860 |

| Melanoma malignum | BRAF, KIT | 1p36 | 155600 |

| Meningioma Skull base meningioma |

ATP1A2, SST | 10q23.31, 17q21.2, 22q12-13 | 607174 |

| Metastases (breast, lung, kidney, gastrointestinal tract) | Multiple molecular elements involved in progression of specific tumors | ||

| Nasopharyngeal carcinomas | TP53, ZMYND10 | 4p15.1-q12, 6p21.3 | 607107, 161550 |

| Neurilemmoma | MYH8, VIM | 22q11.23, 22q12.2 | 162091 |

| Neuroma | NF2 | 22q12.2 | 101000 |

| Paraganglioma | SDHD, SDHAF2, SDHB, SDHC, SDHA | 11q23.1, 1p36, 1q21, 11q13, 5p15 | 168000, 115310, 605373, 601650, 614165 |

| Plasmocytoma | IRF4, CCND1 | 22q11.23 | 605017 |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | TTN, FHL2, PAX3 | 11p15.4, 1p36.13, 2q36.1, 13q14.11 | 268210, 268220 |

| Salivary glands tumors | DENR, XIAP | 8q12.1, | 181030 |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | TNFRSF10B, ING1 | 8p21.3, 10q23.31, 13q34 | 275355 |

| Teratoma | AFP, CGA, CGB | Multiple changes | 273120 (pineal teratoma) |

| Tumors of the hypophysis (prolactinoma) | AIP | 11q13.2 | 600634, 102200 |

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Financial disclosure

None declared.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Dr. Matthew Ibbs, Ph.D., for his help in editing this manuscript, for his comments and suggestions to improve this manuscript.

References

- 1.Barnes L., Eveson J.W., Reichart P., Sidransky D. IARC Press; Lyon: 2005. Head and neck tumors. Pathology and genetics. WHO classification of tumors. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnes L., Kapadia S.B. The biology and pathology of selected skull base tumors. J Neurooncol. 1994;20:213–240. doi: 10.1007/BF01053041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bandurska-Luque A., Piotrowski T., Skrobała A., Ryczkowski A., Adamska K., Kaźmierska J. Prospective study on dosimetric comparison of helical tomotherapy and 3DCRT for craniospinal irradiation – a single institution experience. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2015;20:145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.rpor.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Radner H., Katenkamp D., Reifenberger G., Deckert M., Pietsch T., Wiestler O.D. New developments in the pathology of skull base tumors. Virchows Arch. 2001;438:321–335. doi: 10.1007/s004280100395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah J., Singh B. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2012. Jatin Shah's head and neck surgery and oncology. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calzada A.P., Abemayor E., Wong D.T.W. Molecular pathology of head and neck cancer. In: Cheng L., Eble J.N., editors. Molecular surgical pathology. Springer; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fletcher C.D.M., editor. Diagnostic histopathology of tumors. 3rd ed. Churchill Livingstone; 2007. Larynx and trachea. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kassam A.B., Prevedello D.M., Carrau R.L. Endoscopic endonasal skull base surgery: analysis of complications in the authors’ initial 800 patients. J Neurosurg. 2011;114:1544–1568. doi: 10.3171/2010.10.JNS09406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Safdari Y., Khalili M., Farajnia S., Asgharzadeh M., Yazdani Y., Sadeghi M. Recent advances in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma – a review. Clin Biochem. 2014;47:1195–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2014.05.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burduk P.K., Bodnar M., Sawicki P. Expression of metalloproteinases 2 and 9 and tissue inhibitors 1 and 2 as predictors of lymph node metastases in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 2015;37:418–422. doi: 10.1002/hed.23618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.emedicine.medscape.com/article/250237-overview [last accessed 22.09.14]

- 12.Teoh J.W., Yunus R.M., Hassan F., Ghazali N., Abidin Z.A.Z. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma in dermatomyositis patients: a 10-year retrospective review in Hospital Selayang, Malaysia. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother J Gt Cancer Cent Pozn Polish Soc Radiat Oncol. 2014;19:332–336. doi: 10.1016/j.rpor.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chua M.L.K., Wee J.T.S., Hui E.P., Chan A.T.C. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Lancet. 2015 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00055-0. Online. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee A.W.M., Ma B.B.Y., Ng W.T., Chan A.T.C. Management of nasopharyngeal carcinoma: current practice and future perspective. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3356–3364. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.60.9347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prabhu S.S., Demonte F. Treatment of skull base tumors. Curr Opin Oncol. 2003;15:209–212. doi: 10.1097/00001622-200305000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsai E.C., Santoreneos S., Rutka J.T. Tumors of the skull base in children: review of tumor types and management strategies. Neurosurg Focus. 2002;12:e1. doi: 10.3171/foc.2002.12.5.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Negoto T., Sakata K., Aoki T. Sequential pathological changes during malignant transformation of a craniopharyngioma: a case report and review of the literature. Surg Neurol Int. 2015;6:50. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.154274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.www.pathologyoutlines.com [last attempt 24.10.14]

- 19.Fernandez-Miranda J.C., Gardner P.A., Snyderman C.H. Craniopharyngioma: a pathologic, clinical, and surgical review. Head Neck. 2012;34:1036–1044. doi: 10.1002/hed.21771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thompson L.D.R. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2013. Head and neck pathology. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dillon P.M., Chakraborty S., Moskaluk C.A., Joshi P.J., Thomas C.Y. Adenoid cystic carcinoma: a review of recent advances, molecular targets, and clinical trials. Head Neck. 2014 doi: 10.1002/hed.23925. Online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wierzchowska M., Bodnar M., Burduk P.K., Kaźmierczak W., Marszałek A. Rare benign pleomorphic adenoma of the nose: short study and literature review. Videosurg Other Miniinvas Tech. 2015;10:332–336. doi: 10.5114/wiitm.2014.47370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kraft S., Granter S.R. Molecular pathology of skin neoplasms of the head and neck. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014;138:759–787. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2013-0157-RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olender T., Safran M., Edgar R. An overview of synergistic data tools for biological scrutiny. Isr J Chem. 2013;53:185–198. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Delgado-Lopez P.D., Martin-Velazco V., Galacho-Harriero A.M., Castilla-Diez J.M., Rodriguez-Salazar A., Echevarria-Itulbe C. Large chondroma of the dural convexity in patient with Noonan's syndrome. Case Rep Rev Lit Neurocir Astur. 2007;18:241–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coca-Pelaz A., Rodrigo J.P., Triantafyllou A. Chondrosarcomas of the head and neck. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;271:2601–2609. doi: 10.1007/s00405-013-2807-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reilly B.K., Kim A., Peña M.T. Rhabdomyosarcoma of the head and neck in children: review and update. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;79:1477–1483. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2015.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fletcher C.D.M., editor. Diagnostic histopathology of tumors. 3rd ed. Churchill Livingstone; 2007. Tumors of the central nervous system. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosai J., editor. Rosai and Ackerman's surgical pathology. Mosby Elsevier; New York: 2011. Central nervous system. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Forst D.A., Nahed B.V., Loeffler J.S., Batchelor T.T. Low-grade gliomas. Oncologist. 2014;19:403–413. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shibuya M. Pathology and molecular genetics of meningioma: recent advances. Neurol Med Chir. 2015;55:14–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Su S.Y., Bell D., Hanna E.Y. Esthesioneuroblastoma, neuroendocrine carcinoma, and sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma: differentiation in diagnosis and treatment. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;18:S149–S156. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1390014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dulguerov P., Allal A.S., Calcaterra T.C. Esthesioneuroblastoma: a meta-analysis and review. Lancet Oncol. 2001;2:683–690. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(01)00558-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McGovern S.L., Aldape K.D., Munsell M.F., Mahajan A., DeMonte F., Woo S.Y. A comparison of World Health Organization tumor grades at recurrence in patients with non-skull base and skull base meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 2010;112:925–933. doi: 10.3171/2009.9.JNS09617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fletcher C.D.M., editor. Diagnostic histopathology of tumors. 3rd ed. Churchill Livingstone; 2007. Tumors of pituitary gland. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Offergeld C., Brase C., Yaremchuk S. Head and neck paragangliomas: clinical and molecular genetic classification. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2012;67:19–28. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2012(Sup01)05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walter C., Ziebart T., Sagheb K., Rahimi-Nedjat R.K., Manz A., Hess G. Malignant lymphomas in the head and neck region--a retrospective, single-center study over 41 years. Int J Med Sci. 2015;12:141–145. doi: 10.7150/ijms.10483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Singh A.D., Chacko A.G., Chacko G., Rajshekhar V. Plasma cell tumors of the skull. Surg Neurol. 2005;64:434–438. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2005.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bachar G., Goldstein D., Brown D. Solitary extramedullary plasmacytoma of the head and neck – long-term outcome analysis of 68 cases. Head Neck. 2008;30:1012–1019. doi: 10.1002/hed.20821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ezzat S., Asa S.L., Couldwell W.T. The prevalence of pituitary adenomas: a systematic review. Cancer. 2004;101:613–619. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heaney A.P. Clinical review: pituitary carcinoma: difficult diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:3649–3660. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sweiss R.B., Shweikeh F., Sweiss F.B., Zyck S., Dalvin L., Siddiqi J. Suprasellar mature cystic teratoma: an unusual location for an uncommon tumor. Case Rep Neurol Med. 2013;2013:180497. doi: 10.1155/2013/180497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anderson P.J., David D.J. Teratomas of the head and neck region. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2003;31:369–377. doi: 10.1016/s1010-5182(03)00067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mendenhall W.M., Mendenhall C.M., Lewis S.B., Villaret D.B., Mendenhall N.P. Skull base chordoma. Head Neck. 2005;27:159–165. doi: 10.1002/hed.20144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Patel S.G., Singh B., Polluri A. Craniofacial surgery for malignant skull base tumors: report of an international collaborative study. Cancer. 2003;98:1179–1187. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]