Abstract

Small copy number variations (CNVs) have typically not been analyzed or reported in clinical settings and hence have remained underrepresented in databases and the literature. Here, we focused our investigations on these small CNVs using chromosome microarray analysis (CMA) data previously obtained from patients with atypical characteristics or disorders of sex development (DSD). Using our customized CMA track targeting 334 genes involved in the development of urogenital and reproductive structures and a less stringent analysis filter, we uncovered small genes with recurrent and overlapping CNVs as small as 1 kb, and small regions of homozygosity (ROHs), imprinting and position effects. Detailed analysis of these high-resolution data revealed CNVs and ROHs involving structural and functional domains, repeat elements, active transcription sites and regulatory regions. Integration of these genomic data with DNA methylation, histone modification and predicted RNA expression profiles in normal testes and ovaries suggested spatiotemporal and tissue-specific gene regulation. This study emphasized a DSD-specific and gene-targeted CMA approach that uncovered previously unanalyzed or unreported small genes and CNVs, contributing to the growing resources on small CNVs and facilitating the narrowing of the genomic gap for identifying candidate genes or regions. This high-resolution analysis tool could improve the diagnostic utility of CMA, not only in patients with DSD but also in other clinical populations. These integrated data provided a better genomic-epigenomic landscape of DSD and greater opportunities for downstream research.

Introduction

Over the past decade, the utilization of chromosome microarray analysis (CMA) as a clinical diagnostic tool has accumulated a massive amount of copy number variation (CNV) data, most of which are large or with sizes greater than the arbitrary set reporting limits, e.g., several hundreds of thousands of base pairs (kilobase/kb) to millions of base pairs (megabase/Mb). Although some of these CNVs have already been implicated in neurodevelopmental disorders and contiguous gene syndromes,1–3 many have remained as variants of uncertain clinical significance, with critical regions or causative genes yet to be identified. In clinical CMA, CNVs smaller than the analysis cutoff (e.g., ⩽25–50 kb, ⩽25 markers; referred to as ‘small CNVs’ hereafter) have either not been analyzed or not been reported. Thus far, only a few CMA studies have described the detection of such CNVs in human genetic disorders, e.g., 2.2–49 kb in idiopathic autism and/or intellectual disability,4 psoriasis,5 Crohn's disease,6 autism spectrum disorder7 and congenital heart disease.8 Genome sequencing data have also been utilized in finding CNVs as small as 100 base pairs (bp) to 2.8 kb in patients with autism spectrum disorder and congenital heart disease.8–10 Despite such reports, small CNV maps for clinical populations remain underrepresented in the existing databases and literature. In contrast, publicly available high resolution CNV maps (with CNVs as small as 50 bp) have been constructed and recently updated,11–13 providing comparable resources for the appropriate annotation and interpretation of small CNVs detected in clinical settings. With the availability of these genomic data, we are now poised to build small CNV maps that could aid in narrowing the genomic gap in human genetic disorders, including disorders of sex development (DSDs). DSDs constitute a group of rare and heterogeneous conditions characterized by atypical manifestations of chromosomal, gonadal and phenotypic sex, resulting in differences in the development of the urogenital and reproductive structures. DSDs are classified into three major groups; XX, DSD; XY, DSD; and sex chromosome DSD.14,15

In a significant portion of DSD cases, the genetic etiology remains elusive. Previous CMA studies in DSD have described a few small CNVs (0.2–50 kb),16–20 most of which have remained uncharacterized. Here, we focused our retrospective CMA on previously unanalyzed small CNVs and other genomic regions, including small regions of homozygosity (ROHs), imprinting and position effects. We used these high resolution data to investigate salient genomic features, e.g., CpG islands (CGIs), structural regions, functional domains and repeat elements, as well as the DNA methylation, histone modification and RNA expression profiles of these predicted regulatory regions in the normal testis and ovary.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Washington University in St Louis School of Medicine.

Patient population

Our retrospective study was performed using CMA data obtained from 52 patients referred to our center from 2008 to 2015 for mild to severe DSDs, atypical secondary sexual development, Turner syndrome or stigmata and sex chromosome anomalies. XY and XX sex chromosome complements accounted for 63% and 21% of the patients, respectively (Table 1). Karyotypes with sex chromosome anomalies were also observed: 6% with loss of X; 4% with XXY; and 6% with mosaicism, X/XX (n=2) and X/XY (n=1).

Table 1. Summary of CNVs and ROH overlapping with DSD genes in our patient cohort.

| D# | DSD | Sex Chrom | Clinical CMA Finding | Total CNV Per Px | Total Ov CNVs Per Px | Total Loss Per Px | Total Ov Loss Per Px | Loss | Total Gain Per Px | Total Ov Gain Per Px | Gain | Total ROH Per Px | Total ROH Ov Genes Per Px | ROH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 12,576 | 301 | 6,475 | 162 | 6,141 | 141 | 3,421 | 333 | ||||||

| Range | 67–817 | 0–18 | 44–295 | 0–12 | 15–623 | 0–16 | 14–125 | 0–16 | ||||||

| D1 | SSC | XX | N | 373 | 5 | 160 | 4 | ESR2, GRIP1, ROCK2, CHD7 | 213 | 1 | FLNA | 74 | 7 | EP300, VAMP7, OCA2, AR, FRG1BP, GATA6, SIM1 |

| D2 | AG, E, UT, M, SA, KA | XY | N | 376 | 4 | 244 | 2 | TP63, WWOXa | 132 | 2 | KRAS, WWOX | 46 | 2 | EP300, OCA2 |

| D3 | SSC | X/XX | P | 355 | 3 | 119 | 3 | AR, ANOS1 (KAL1), FGD1 | 236 | 0 | none | 66 | 7 | OCA2, PTPN11, CYP26B1, FGF10, DHH, HSD17B3, SIM1 |

| D4 | H | XY | V | 200 | 5 | 127 | 3 | FLT1 (2), CREBBP | 73 | 2 | PTCH1, FGFR2 | 75 | 8 | FRG1BP, BBS1, BBS12, FGF2, FGF8, CYP17A1, GHR, CALCA |

| D5 | H | XY | V | 158 | 2 | 73 | 1 | PCDH17 | 85 | 1 | GRIP1 | 55 | 3 | PTPN11, BBS4, GHR |

| D6 | H | XY | N | 256 | 3 | 83 | 0 | none | 173 | 3 | KRAS, NOTCH3, PDGFRA | 17 | 1 | PTPN11 |

| D7 | AG, H, AD | XY | N | 274 | 4 | 144 | 1 | RAF1a | 130 | 3 | KRAS, RAF1, PTCH1 | 15 | 1 | PCDH17 |

| D8 | SSC | XX | N | 195 | 1 | 70 | 1 | WWOX | 125 | 0 | none | 18 | 1 | ATRX |

| D9 | H | XY | V | 405 | 7 | 215 | 5 | ESR2, PCDH17, PSCK1, WWOX, NR5A1 | 190 | 2 | FLNA, CHD7 | 75 | 8 | OCA2, PTPN11, ESR1, FOXL2, PAX6, KISS1, SIM1, WNT2 |

| D10 | AG, H, END | XXY | P | 281 | 8 | 198 | 4 | CTNNA3, ESR2, PCKS1, WWOX | 83 | 4 | NLGN4X, ATRX, NR0B1, SHOX | 77 | 4 | OCA2, SIM1, ARL6, GATA6 |

| D11 | H | XY | V | 214 | 0 | 88 | 0 | none | 126 | 0 | none | 49 | 7 | OCA2, PTPN11, SRD5A2, NR5A2, SUPT3H, GATA6, PAX6 |

| D12 | AG | XY | N | 339 | 9 | 179 | 5 | AHRR, BNC2, WWOX (2), GATA4 | 160 | 4 | NOTCH3, PTCH1b, SHOX, SNRPN | 63 | 6 | PTPN11, SRD5A2, PTCH1, BBS1, CYP26B1, MAPK3 |

| D13 | H, M, UT, CH | XY | N | 410 | 7 | 232 | 5 | EP300, ESR2 (2)a, FAM167-AS1, MOV10L1 | 178 | 2 | ESR2, GNRH1 | 59 | 2 | PTPN11, RHOA |

| D14 | AG | XY | P | 586 | 9 | 221 | 4 | FAM167A-AS1, INSR, MOV10L1, WWOX | 365 | 5 | CNTNAP3, CTNNA3, CTNNB1, GFRA1, PTPN11 | 15 | 1 | EP300 |

| D15 | AG, KA | XX | N | 711 | 10 | 295 | 4 | BNC2, GRIP1, ROCK2, MTHFR | 416 | 6 | CNTNAP3, ESR2, FGR1BP, NOTCH3, PIP5K1B, PTPN11b | 107 | 6 | PCDH17, PTPN11, ATRX, CTNNA3, FGD1, GATA6 |

| D16 | H, SA | XY | N | 353 | 10 | 121 | 4 | AHRR, TP63, WWOX, SOS1 | 232 | 6 | CTNNB1, ESR2, KANK1, NOTCH3, OCA2, PTPN11 | 60 | 10 | SRD5A2, GFRA1, SUPT3H, BBS4, FGF8, CYP17A1, GHR, HSD3B1, HSD3B2, MAPK3 |

| D17 | AG, SA, H SSC | XY | N | 333 | 7 | 118 | 1 | AHRR | 215 | 6 | CTNNB1, CXCL12, KANK1, NOTCH3, PDFGRA, WWOX | 125 | 12 | KRAS, NOTCH1, PCDH17, GRIP1, CYP26B1, GHR, HSD17B4, HSD3B1, HSD3B2, LHX3, SOS1, PTGDS |

| D18 | GA | XX | N | 817 | 14 | 194 | 1 | WWOXa | 623 | 13 | CNTNAP3, CTNNB1, FRG1BP, KANK1, NOTCH3, OCA2 b, PDGFRA, PIP5K1B, PTPN11 b, RAF1, TGFB1, WWOX, HSD17B3 | 90 | 8 | EP300, OCA2, PTPN11, ATRX, VAMP7, AR, HHAT, PAX6 |

| D19 | H, SA | XY | N | 366 | 3 | 97 | 0 | none | 269 | 3 | GFRA1, KRAS, NOTCH3 | 72 | 5 | OCA2, PTPN11, ARL6, CYP26B1, GHR |

| D20 | CH, H, UT, KA, UA | XY | V | 279 | 4 | 125 | 3 | DMD, WWOX, CAMK1D | 154 | 1 | KANK1 | 23 | 1 | CTNNA3 |

| D21 | H, SA, UA | XY | V | 800 | 18 | 177 | 2 | AHRR, WWOXa | 623 | 16 | CTNNA3, CTNNB1, CXCL12, ESR2, FLNA, NOTCH3, OCA2 (2), PDGFRA, PTCH1 (2), PTPN11, SNRPN, TGFB1, WWOX, BBS9 | 82 | 3 | BBS1, DHH, PTGS2 |

| D22 | END | X/XX | P | 134 | 3 | 100 | 3 | FRAS1, TP63, WWOX | 34 | 0 | none | 74 | 7 | PTPN11, CYP26B1, RHOA, WNT2, STAR, FGFR1, CYP19A1 |

| D23 | AG, H, END | XY | N | 75 | 3 | 59 | 2 | DMD, POR | 16 | 1 | DMD | 79 | 8 | PTCH1, APOA1, BBS1, FGF2, DHCR7, GHR, LEPR, ARL6 |

| D24 | H, UT | XY | N | 104 | 3 | 89 | 3 | FRAS1, INSR, PTPN11 | 15 | 0 | none | 83 | 4 | EP300, SRD5A2, FGF8, CYP17A1 |

| D25 | H, M, SA | XY | N | 67 | 7 | 46 | 5 | DHRSX (2), NR5A2 (2), SOX9 | 21 | 2 | DHRSX, NLGN4X | 80 | 16 | EP300, OCA2, PCDH17, FRG1BP, GFRA1, SUPT3H, BBS5, FGF7, COPS2, EMX2, FGF10, GHR, HSD17B3, WNT2, FRAT1, MAPK3 |

| D26 | AG, SA, M, H | XY | N | 110 | 4 | 84 | 4 | DHRSX (2), FRAS1, WWOX | 26 | 0 | none | 82 | 14 | NOTCH1, OCA2, FRG1BP, CNTNAP3, BBS4, GHR, HSD17B3, NOTCH4, CYP21A2, PAX6, SOS1, SOX8, PTGDS, SRD5A2 |

| D27 | SSC | X | P | 177 | 4 | 117 | 1 | CTNNA3 | 60 | 3 | PIP5K1B, TP63, ESR1 | 86 | 4 | PTPN11, CXCL12, BBS4, CREBBP |

| D28 | GA | XY | N | 90 | 3 | 69 | 1 | NR5A2 | 21 | 2 | DMD, NR0B1 | 96 | 6 | OCA2, PCDH17, CHD7, CYP26B1, GHR, WNT2 |

| D29 | AG, C | XX | V | 161 | 13 | 130 | 9 | DMD (6), NLGN4X, NOTCH1, WWOX | 31 | 4 | DMD (2), EP300, NLGN4X | 29 | 3 | PCDH17, FGF10, MAPK3 |

| D30 | AG, UT | XXY | V | 164 | 9 | 69 | 2 | SRD5A2, ESR1 | 95 | 7 | ATRX, DMD (5), NR0B1 | 102 | 3 | EP300, PTPN11, CYP26B1 |

| D31 | H, KA | XY | N | 96 | 6 | 62 | 1 | HHAT | 34 | 5 | AR, DHRSX, DMD (2), NLGN4X | 50 | 8 | PTPN11, BBS1, CYP11A1, CYP19A1, GATA6, CYP21A2, MAPK14, RHOA |

| D32 | M | XY | V | 74 | 4 | 58 | 4 | DHRSX, DMD, NOTCH1, WWOX | 16 | 0 | none | 19 | 3 | PAX6, STAR, WT1 |

| D33 | TS | X | P | 133 | 2 | 99 | 1 | MOV10L1 | 34 | 1 | WWOX | 79 | 6 | EP300, OCA2, PROP1, MAPK1, FOXL2, CYP26B1 |

| D34 | SSC, TS | XX | N | 232 | 10 | 138 | 2 | AXIN1, WNT2 | 94 | 8 | DMD (4), ESR2, NLGN4X, PBX1, TP63 | 111 | 15 | FRAS1, OCA2, AR, ATRX, CTNNA3, FLNA, CYP19A1, FGF10, FOXL2, MAMLD1, INSRR, SOX3, STAR, FGFR1, NCOR1 |

| D35 | UT, END | XY | N | 126 | 1 | 94 | 1 | MOV10L1 | 32 | 0 | none | 67 | 11 | NOTCH1, OCA2, PTPN11, BBS1, BBS4, COPS2, FGF7, FRAT1, GHR, PTGDS, PTGS2 |

| D36 | UT, KA | XY | N | 128 | 4 | 84 | 1 | VAMP7 | 44 | 3 | BNC2, DHRSX, DMD | 78 | 6 | PTPN11, FRG1BP, CYP17A1, CALCA, BBS1, ARL6 |

| D37 | AG, H, SA | XY | N | 124 | 4 | 94 | 1 | MOV10L1 | 30 | 3 | ATRX, CTNNA3, DMD | 75 | 6 | PTPN11, SRD5A2, ALG12, MAPK11, RHOA, SOS1 |

| D38 | END | XY | N | 163 | 8 | 122 | 7 | DMD (2), SUPT3H, TP63, WWOX, FGFR2, SOX9 | 41 | 1 | PBX1 | 14 | 0 | none |

| D39 | TS | X | P | 177 | 2 | 124 | 2 | SRD5A2, WWOX | 53 | 0 | none | 80 | 10 | EP300, PTPN11, CTNNA3, PTGS2, HNF1B, GRNHR, FGF10, CYP17A1, AMHR2, ARL6 |

| D40 | AG, H, AD, UT, M, SA | XY | N | 245 | 5 | 188 | 4 | DHRSX, DMD (2), NLGN4X | 57 | 1 | KAL1 | 37 | 16 | AHRR, PCDH17, PTPN11, KANK1, STAR, FGFR1, HSD17B4, GDF9, FZD4, COPS2, FGF7, CYP19A1, BBS4, CYP11A1, CHD7, AMHR2 |

| D41 | AG, M, CH, H | XY | N | 169 | 6 | 103 | 5 | DHRSX, DMD (2), WWOX, NOTCH2 | 66 | 1 | TP63 | 87 | 7 | EP300, PCDH17, PTPN11, SRD5A2, BBS4, STAR, FGFR1 |

| D42 | H, CH | XY | V | 267 | 13 | 199 | 7 | AXIN1, DMD (2)a, ESR2a, FRAS1, TP63a, WWOX | 68 | 6 | DMD, ESR2, OCA2, PBX1, PTCH1, TP63 | 16 | 1 | PTPN11 |

| D43 | H, UT | XY | N | 92 | 4 | 63 | 3 | CTNNA3, KANK1, WWOX | 29 | 1 | TP63 | 78 | 10 | AHRR, PTPN11, PTCH1, STAR, FGFR1, SOX2, SOS1, HSD3B1, HSD3B2, NOTCH2 |

| D44 | TS | XX | V | 213 | 10 | 142 | 4 | AXIN1, DMD (2), NLGN4X | 71 | 6 | DMD (3), ESR2, PBX1, ARX | 77 | 6 | AR, ATRX, CTNNA3, FLNA, FGD1, RHOA |

| D45 | GA, KA | XX | V | 126 | 4 | 94 | 2 | TP63, WWOX | 32 | 2 | WWOX, DHRSX | 99 | 8 | EP300, OCA2, SRD5A2, ARX, GATA4, RHOA, ARL6, MAMLD1 |

| D46 | AG, UT, M, CH | X/XY | P | 189 | 8 | 163 | 8 | CTNNA3, DHRSX (2), MOV10L1, PIP5K1B, SHOX, VAMP7, SOX9 | 26 | 0 | none | 93 | 8 | PTPN11, SRD5A2, GFRA1, NR5A2, BBS1, GATA6, PTGS2, MAPK3 |

| D48 | H, CH, UT | XY | N | 192 | 10 | 126 | 7 | DHRSX, DMD (4), NLGN4X, SUPT3H | 66 | 3 | EP300, PBX1, TP63 | 23 | 3 | OCA2, PIP5K1B, CTNNA3 |

| D49 | AG | XY | N | 98 | 0 | 70 | 0 | none | 28 | 0 | none | 75 | 10 | OCA2, PTPN11, CTNNA3, SUPT3H, BBS1, BBS4, FREM2, STAR, FGFR1, ARL6 |

| D50 | C, UT, END | XY | N | 125 | 1 | 94 | 1 | DMD | 31 | 0 | none | 71 | 5 | EP300, OCA2, PTPN11, BBS1, FGF2 |

| D51 | AD, M, H, UT | XX | V | 149 | 4 | 105 | 4 | AXIN1, DHRSX, DMD, FGF7 | 44 | 0 | none | 108 | 14 | NOTCH1, PTPN11, AR, ATRX, FLNA, FRG1BP, PTCH1, VAMP7, ARX, BBS1, CYP26B1, GHR, MAMLD1, PTGDS |

| D52 | AG, C, UT | XX | N | 217 | 13 | 166 | 12 | AXIN1, BNC2, DMD (7)a, NOTCH1, TP63, SOX9 | 51 | 1 | DMD | 25 | 3 | NOTCH4, CYP21A2, RHOA |

| D53 | M | XX | N | 78 | 0 | 44 | 0 | none | 34 | 0 | none | 85 | 9 | PTPN11, PCDH17, OCA2, AR, ATRX, FLNA, VAMP7, FGD1, ARX |

(n)—number in parenthesis indicates ⩾1 CNV per gene per patient (loss/loss, gain/gain).

*genes with both CNV and ROH.

Clinical CMA Finding: N, normal; V, variant of uncertain clinical significance; P, pathogenic.

DSD—atypical sex development findings; Abbreviations: AD, adrenal anomalies; AG/GA, ambiguous genitalia or genital anomalies; CH, chordee; CMA, chromosome microarray analysis; CNV, copy number variation; DSD, disorders of sex development; END, endocrine findings; H/E, hypospadias or epispadias; KA, kidney anomalies; M/C, micropenis or clitoromegaly; ROH, region of homozygosity; SA, scrotal anomalies; SSC, secondary sexual characteristics; TS, Turner syndrome or stigmata; UA, urethral anomalies; UT, undescended testis or inguinal gonads.

gene with both CN loss and gain in a patient.

gene with both CNV and ROH in a patient.

Clinical CMA platform and analysis software

Clinical CMA was performed on two Affymetrix (Affymetrix, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) platform types (Table 1): Whole Genome-Human SNP Array 6.0 (40% of patients; 2008–2012; patients D1-D20, D53) and CytoScan HD (60% of patients; 2012–2015; D21-D52). The latter has a higher resolution (1 probe/880 bp; 2.6 million probes-1.9 million CN and non-polymorphic, 750,000 single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) probes) than the former (approximately 1.8 million CN and SNP probes), and it encompasses almost all of known OMIM and RefSeq genes. CMA data were compared from control individuals (270 HapMap and 100 in-house) and from 380 phenotypically normal cohorts (284 HapMap and 96 blood samples from 186 female and 194 male patients). Copy number analysis was performed using the Affymetrix Genotyping Console and Chromosome Analysis Suite software programs. All of the genomic linear positions were based on human genome reference version UCSC Genome Assembly GRCh37/hg19.

Retrospective CMA approach

A total of 334 genes obtained from published clinical reports, reviews, CMA studies and the OMIM (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man) database (http://www.omim.org/) were included in constructing a customized CMA ‘DSD Track’ (Supplementary Table S1; listed by size). These genes have been associated with the development of adrenal, urogenital and other reproductive structures, as well as with sexual dimorphism. Their sizes and chromosome locations (in bp coordinates) were also noted. CMA data from 52 patients were analyzed using a 1 kb filter and 1 probe (versus clinical limits of 25–50 kb, 25 probes). Gene-desert regions known to cis-regulate genes were used to build a ‘position effect track.’ Known imprinting genes (www.geneimprint.com) were also collated and used to build the ‘imprinting track.’ To filter the CNVs and ROHs overlapping with genes (DSDs, imprinted and position effects), the ‘overlap map’ function of the Chromosome Analysis Suite software (Affymetrix) was selected, which facilitated the filtration of CNVs and ROHs of interest from the remaining intervals not overlapping with DSD genes.

Probe coverage

The majority of the genes considered in this study with or without CNVs and/or ROHs showed good or proportional probe coverage (Supplementary Tables S3, S4, S5, S6 and S23). Although no SNPs or CN coverage was seen in approximately 12% (n=24), multiple probes flanked these genes. Probe coverage was also verified from the Affymetrix website (https://www.affymetrix.com/analysis/netaffx/showresults.affx).

In silico investigations

All of the small CNVs and ROHs that overlapped with DSD genes were further analyzed for detailed genomic and epigenomic features using publicly available databases. We aligned the CNVs detected from our study with the following tracks from the UCSC Genome Browser21 (http://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgGateway): RefSeq genes; common CNV data (inclusive and stringent data) by Zarrei et al.,13 obtained from DGV (database of genomic variants; http://dgv.tcag.ca/gb2/gbrowse/dgv2_hg19/); the ClinGen database, which curates benign, uncertain clinical significance likely benign (UCS LB), UCS likely pathogenic (LP), UCS and curated pathogenic genes; DECIPHER22 (https://decipher.sanger.ac.uk/); Segmental Duplications; CGIs, UniProt/SwissProt Protein and Secondary Annotations for regions and domains; and Transcription Factor ChIP for predicted transcription factor binding sites. DECIPHER was also investigated for CNVs overlapping with our data, including their sizes, sex chromosome complements, types of CNVs and proportions of small CNVs with DSD phenotypes.

We also aligned our small CNV data set with the WashU Epigenome Browser23 (http://epigenomegateway.wustl.edu/browser/) to investigate the following features: RefSeq genes; CGIs; repeat elements; chromHMM of the ovary for predicted regulatory regions; H3K27Ac and H3K4me1 of the ovary (histone regions predicted to be regulatory); methylC-seq of the fetal testis and ovary for DNA methylation (CGI or regulatory); RNA-seq of fetal and adult ovaries for predicted RNA expression; and cis (local) and trans (interchromosomal) interactions (human foreskin fibroblast, high-content genome conformation capture; density map or circle plot representation).

We also used the following databases for correlating molecular function with the biological processes involved in DSD genes: UniProt (http://www.uniprot.org/), BGee (http://bgee.unil.ch/); GeneMania (http://www.genemania.org/) and STRING (http://string-db.org/) for the genetic and physical interactions of these genes.

Results

Small CNV discoveries

We designed a customized CMA track targeting 334 genes associated with the development of urogenital and other reproductive structures (referred to as ‘DSD track’ and ‘DSD genes’ hereafter) (Supplementary Table S1). The majority of these genes are mapped on chromosomes X, 9 and 1, and approximately 60% of them are ⩽50 kb (Supplementary Figures S1A and SB), e.g., 897 bp (SRY) and 5.9 kb (SOX9). Using 1 kb as the lowest limit of detection, our retrospective CMA of 52 unrelated patients revealed a total of 12,576 CNVs: 6,475 losses (51%) and 6,141 gains (49%) (Table 1). We used the ‘overlap map’ function of the analysis software to expedite the filtration of 301 CNVs overlapping with 68 DSD genes from all of the others, reducing the number of variants for analysis by approximately a hundredfold (Tables 1 and 2, Supplementary Table S2). CN losses accounted for 53% of the CNVs (n=162; 75% CN=1, 25% CN=0), while 47% were CN gains (n=141; 42% CN=3, 42% CN=4, 16% CN=2). Using the haploinsufficiency index scoring from DECIPHER,24 74% (n=121) of the total CN losses involving 36 genes were predicted to be haploinsufficient, in the range of 0.06% (ESR1) to 21.2% (CAMK1D) (Supplementary Table S2). From the recently generated small CNV map obtained from normal populations,13 we compared the 21 homozygous losses (CN=0) involving NOTCH1, SUPT3H, WWOX and DMD detected in our study with the null CNVs consisting of insignificant, enriched, paralogous CN variable regions, and none were found to be overlapping.

Table 2. Summary of DSD genes with recurrent and overlapping CNVs and ROH.

| Gene | Chrom Locus | Gene Size (Kb) | n Px CNV ROHa | total CNV | Loss | Gain | CN State | CNV Size (Kb) | Probes | ROH | # Recurrent CNV (n Px)b | Same Exon/Intron CNV (n Px)b | Non-Ovc CNVs | CNV with Intact Gened |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | 5–2,220 | 1–32 | 2–55 | 0–33 | 0–23 | 1.1–374 | 0–29 | |||||||

| DMD | Xp21.2 | 2,220.4 | 20 | 54 | 33 | 22 | 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 | 1.1–17.4 | 5–52 | 1 | 4; introns 2 (2), 17 (2), 55 (2), 59 (4) | 12; exons 8–9 (2), 48 (3); introns 1 (4), 2 (8), 7 (4), 9 (4), 44 (4), 55 (4), 59 (6), 60 (6), 62 (2), 74 (2) | 3; exons 18, 40–41, 75–76 | none |

| WWOX | 16q23.1 | 1,113.2 | 22 | 27 | 21 | 6 | 0, 1, 3, 4 | 1.8–148.2 | 3–208 | 0 | 3; intron 5 (5, 7, 2) | 2; introns 5 (20), 8 (3) | 2; exon 9, intron 4 | none |

| NOTCH3 | 19p13.12 | 41.3 | 8 | 8 | 0 | 8 | 3, 4 | 2.4–27 | 6–47 | 0 | 2; exons 1 (3), 2–20 (2) | 1; exons 1–33 (8) | none | none |

| TP63 | 3q28 | 265.9 | 12 | 13 | 7 | 6 | 1, 3, 4 | 1.4–11.8 | 8–36 | 0 | 2; exons 5–7 (4), intron 1 (2) | 2; exons 5–7 (6) | 1; exons 8–10 | none |

| ESR2 | 14q23.2 | 111.5 | 10 | 13 | 6 | 7 | 3, 4, 1 | 1.5–12.8 | 8–38 | 0 | 2; exon 9 (2), disrupted exon 13 (2) | 3; exons 9 (4), 13 (3) | 2; exons 7–8, intron 9 | none |

| AXIN1 | 16p13.3 | 65.2 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 2.1–12.7 | 8–44 | 0 | 1; exon 5 (3) | 1; exon 5 (4) | 1; intron 4 | none |

| KRAS | 12p12.1 | 45.7 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 4.2–12.2 | 20–35 | 1 | 1; disrupted exon 5 (2) | 1; exons 4–5 (4), disrupted exons 4, 5 | none | none |

| TGFB1 | 19q13.2 | 23 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 4.015 | 2 | 0 | 1; exons 6–7 (2) | none | none | none |

| EP300 | 22q13.2 | 87.5 | 15 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 4, 1 | 3.1–3.6 | 14–16 | 12 | 1; exons 7–8 (2) | 1; exons 7–10 (3) | none | none |

| CTNNB1 | 3p22.1 | 41 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 3, 4 | 9.6–19.1 | 13–59 | 0 | 1; exons 9–15 (2) | 1; exons 9–15 (4) | 1; intron 1 | none |

| PTPN11 | 12q24.13 | 91.2 | 32 | 6 | 1 | 5 | 3, 1 | 16.4–37 | 8–38 | 29 | 1; exons 11–16 (5) | none | 1; exon 1 (includes RPL6) | none |

| PDGFRA | 4q12 | 69.4 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 2.9–18.8 | 22–66 | 0 | 1; exons 13–23 (2) | 1; exons 12–23 (4), disrupted exon 23 | none | none |

| MOV10L1 | 22q13.33 | 71.7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 4.6–10 | 5–8 | 0 | 1; exons 16–19 (4) | 1; intron 2 (2) | none | none |

| FRAS1 | 4q21.21 | 486.7 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 11.5 | 8 | 1 | 1; exon 30 (4) | none | none | none |

| BNC2 | 9p22.2 | 461.3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 4, 1 | 1.9–3.7 | 5–12 | 0 | 1; intron 1 (2) | 1; intron 1 (3) | 1; intron 2 | none |

| NLGN4X | Xp22.32 | 338.6 | 8 | 9 | 4 | 5 | 0, 1, 2, 4 | 1.5–4.8 | 7–23 | 0 | 1; intron 2 (3) | 2; introns 2 (5), 3 (3) | none | none |

| NOTCH1 | 9q34.3 | 51.3 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 4.371 | 8 | 4 | 1; intron 2 (3) | none | none | none |

| PBX1 | 1q23.3 | 292.5 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 4 | 1.2–7.1 | 5–8 | 0 | 1; intron 2 (4) | 1; intron 2 (5) | none | none |

| DHRSX | Xp22.33 | 281.5 | 12 | 15 | 11 | 4 | 1, 3, 4 | 1.1–48.8 | 12–106 | 0 | none | 3; exon 3 (2); introns 1 (9), 3 (5) | none | none |

| PCDH17 | 13q21.1 | 97.3 | 11 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 6.653 | 7 | 9 | 1; intron 3 (2) | none | none | none |

| AHRR | 5p15.33 | 134.1 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 8.8–19.8 | 14–19 | 2 | 1; intron 4 (2) | 1; exon 5 (2) | none | none |

| PIP5K1B | 9q21.11 | 303.8 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4, 1 | 1.7–4.1 | 3–8 | 1 | 1; intron 7 (2) | none | 2; exon 13 (1), intron 9 (1) | none |

| OCA2 | 15q13.1 | 344.4 | 24 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 4, 3 | 2.4–29.3 | 8–24 | 20 | 1; intron 19 (3) | none | 2; introns 2, 23 | none |

| SOX9 | 17q24.3 | 5.4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1.6–6 | 8–17 | 0 | 1; 6 Kb (3) | none | 1; 1.6 Kb | none |

| SRD5A2 | 2p23.1 | 56.4 | 11 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1, 3 | 6.9 | 8 | 9 | 1; exons 4–6 (2) (disrupted exon 6) | none | none | none |

| DHRSX | Xp22.33 | 281.5 | 12 | 15 | 11 | 4 | 1, 3, 4 | 1.1–48.8 | 12–106 | 0 | none | 3; exon 3 (2); introns 1 (9), 3 (5) | none | none |

| CXCL12 | 10q11.21 | 14.941 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 3, 4 | 6.9–8.1 | 10–12 | 1 | none | 2; exon 4 (2), disrupted | none | none |

| SHOX | Xp22.33 | 35.1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 4, 3, 1 | 41.5–41.7 | 10–81 | 0 | none | 1; exon 6 (2) | none | 1 (D10) |

| GFRA1 | 10q25.3 | 216.7 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 18.3–22 | 19–21 | 3 | none | 1; exon 5 (2) | none | none |

| FLNA | Xq28 | 26.1 | 8 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3, 2 | 10.7–22.9 | 23–40 | 7 | none | 1; exons 6–48 (3), disrupted exons 22, 48 | none | none |

| AR | Xq12 | 186.6 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1, 2 | 8.4–190.5 | 16–86 | 7 | none | 1; intron 1 (2) | none | none |

| FAM167A-AS1 (C8orf12) | 8p23.1 | 70.3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 15.9–19.2 | 18–20 | 0 | none | 1; intron 1 (2) | none | none |

| RAF1 | 3p25.2 | 80.6 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1, 4 | 3.9–13.6 | 11–32 | 0 | none | 1; intron 1 (1) | 1; exons 3–6 | none |

| INSR | 19p13.2 | 181.746 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 7–29.1 | 5–23 | 0 | none | 1; intron 2 (2) | 1; disrupted exon 22 (ZNF557) | none |

| PTCH1 | 9p22.32 | 65.6 | 8 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 4, 3 | 3.7–16.4 | 13–40 | 4 | none | 1; intron 2 (3) | 3; exons 1–2, 11–12, 14–15 | none |

| SNRPN | 15q11.2 | 154.9 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 14.8–36.5 | 17–34 | 0 | none | 1; intron 2 (2) | none | none |

| SUPT3H | 6p21.1 | 551.3 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0, 1 | 9.8–10 | 8–16 | 5 | none | 1; intron 2 (2) | none | none |

| KANK1 | 9p24.3 | 241.1 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 1, 3, 4 | 4.1–32.1 | 7–41 | 1 | none | 1; intron 6 (3) | 2; exon 6, intron 5 | none |

| CTNNA3 | 10q21.3 | 1776.2 | 14 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 3, 4, 1 | 6.6–92.2 | 5–104 | 7 | none | 1; intron 7 (2) | 5; exon 10, introns 5, 9, 12, 13 | none |

| NR5A2 | 1q32.1 | 149.8 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1.1–4.5 | 6–14 | 2 | none | 1; intron 7 (2) | 1; intron 5 | none |

| ESR1 | 6q25.1 | 296 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1, 3 | 25–28 | 8–28 | 1 | none | 1; intron 7 (2) | none | none |

| ATRX | Xq21.2 | 281.4 | 10 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 2, 3 | 2.2–5.2 | 10–12 | 7 | none | 1; intron 23 (2) | none | 1 (D10) |

| GRIP1 | 12q14.3 | 331.7 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1, 4 | 8.4–23.9 | 11–15 | 1 | none | none | 3; exon 14, introns 1, 5 | none |

| CNTNAP3 | 9p13.1 | 215.5 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 95.7–374.0 | 17–66 | 1 | none | none | 2; exons 1–2, 19–24 | 1 (D18) |

| VAMP7 | Xq28 | 62.5 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1.5–94 | 5–153 | 4 | none | none | 2; exons 6–8 (3'), intron 6 | none |

| FGFR2 | 10q26.13 | 120.1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1, 4 | 4–6 | 6–9 | 0 | none | none | 2; exons 14–15, intron 5 | none |

| FLT1 | 13q12.2 | 194.8 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2.4–11.4 | 5–8 | 0 | none | none | 2; exon 24, intron 3 | none |

| ROCK2 | 2p25.1 | 163 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 28.1–42.2 | 15–19 | 0 | none | none | 2; exons 31–33 (PQLC3), intron 1 | none |

| CHD7 | 8q12.2 | 189.3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1, 4 | 2–11.4 | 3–9 | 2 | none | none | 2; exons 35–38, intron 1 | none |

| NR0B1 | Xp21.2 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 4.9–5.6 | 32–39 | 0 | none | none | 1; exons 1–2, disrupted exon 1 | 2 (D10, D28) |

| PCSK1 | 5q15 | 42.5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 24.8 | 18 | 0 | none | none | 1; exons 1–3 | 1 (D9) |

| ANOS1 (KAL1)e | Xp22.31 | 203.3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1, 2 | 7 | 18 | 0 | none | none | 1; intron 2 | 1 (D3) |

Abbreviations: CNV, copy number variation; ROH, region of homozygosity.

n Px—number of patients with both CNV and ROH.

number of recurrent/overlapping.

number of non-overlapping CNVs; specific exon/intron involved in CNV (number of patients with specific CNV).

CNVs that include an intact smaller gene.

gene names in parenthesis—old name.

Our CMA approach uncovered 284 (94%) small CNVs involving 63 DSD genes (approximately 93%), and 16 (approximately 24%) of these genes were found to be ⩽50 kb (Supplementary Table S2). The highest frequencies of CNVs were observed in DMD, WWOX and DHRSX (Table 1) and on chromosomes X, 16 and 9, while none were found on 11, 18, 21 and Y (Supplementary Figure S1A). Eight genes exhibited 14 CNVs with breakpoints disrupting exons (1.8–29.1 kb; 8–37 markers) that involve critical structural and functional regions or domains and biological processes related to sex development (Supplementary Table S3). Thirteen CNVs revealed breakpoints outside of an intact gene, 10 of which included 8 small genes, e.g., a 5.6 kb gain (NR0B1) (Figure 1a) to a 64 kb gain (GNRH1) (Supplementary Table S2). Identical small CNVs involving 25 genes detected in two or more patients were observed (Table 1): four different recurrent CNVs in DMD (1.4–6.3 kb; 10–40 markers), three in WWOX (7.2–8.8 kb; 12–24 markers), two each in ESR2 (1.8–4.8 kb; 8–26 markers), NOTCH3 (2.8–19.8 kb; 9–46 markers) and TP63 (4.6–8.3 kb; 12–32 markers), and one in 19 genes (1.2–37 kb; 2–66 markers). CNVs with variable sizes (1.1–190 kb) but involved the same intron or exon were observed in 32 genes, while non-recurrent and non-overlapping CNVs were detected in 25 genes.

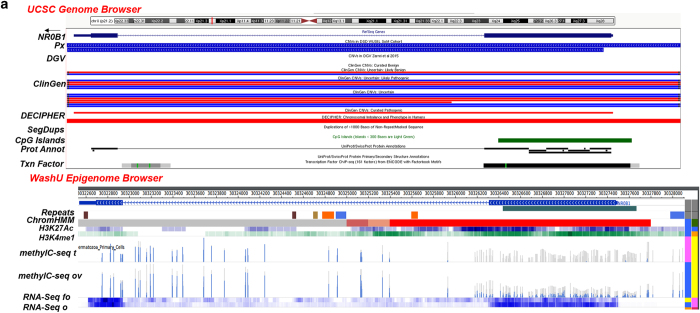

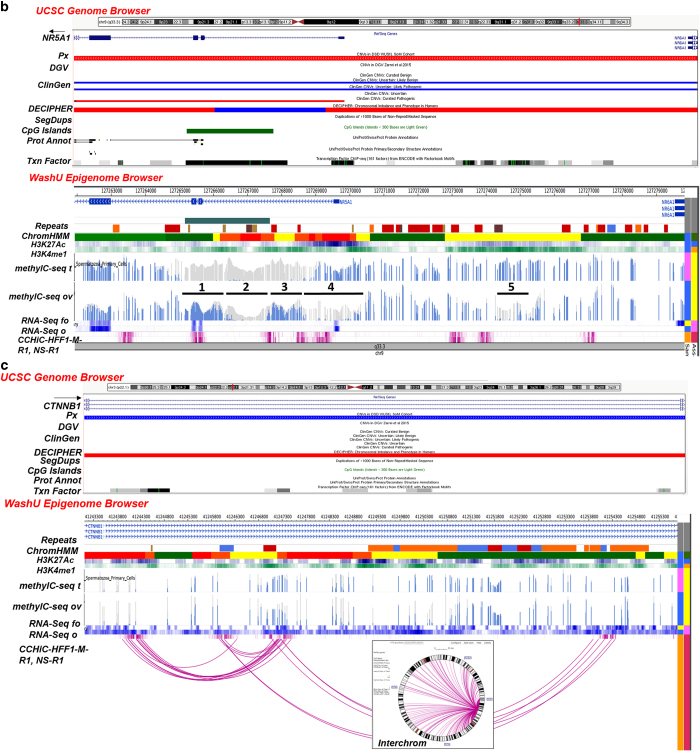

Figure 1.

(a) CN gains overlapping with an intact NR0B1 (5 kb; Xp21.2). UCSC Browser—CN gains (blue) overlapping with an intact NR0B1 (exons 1–2) in 2 patients (Px); D28 (XY) with underdeveloped genitalia (5.6 Kb, 39 markers; chrX:30,322,475–30,328,115) and D30 (XXY) with ambiguous genitalia, undescended testes and small ureters (4.9 kb, 32 markers; chrX:30,322,476–30,327,408). DGV (Zarrei et al.,13)—no overlapping CNVs found. ClinGen—CN gains and losses categorized as uncertain clinical significance (UCS), UCS likely benign (UCS LB), UCS likely pathogenic (UC LP) and a pathogenic loss. DECIPHER—losses in patients with variable findings. Segmental Dups (SegDups)—none. CpG Islands—exon 1. Protein Annotation (Prot Annot)—ligand binding, AF-2 motif, LXXLL motifs 1–3, AA tandem repeat and repeats 1–4. Transcription Factor (Txn Factor)—exons 1 and 2. WashU Epigenome Browser. Repeat Masker (Repeats)—intron 1: LINE (orange), DNA transposon (blue), simple repeat, microsatellite (SR/MS; gold), satellite repeat (SR; brown). ChromHMM—active transcription start site (aTSS) (red); repressed polycomb (gray). Histone Modification—H3K27Ac (acetylation) and H3K4me1 (methylation) marks in the ovary. DNA Methylation (methylC-seq t, ov)—differential profile in exon 1—some DNA in fetal ovary and none in fetal testis). RNA Expression (RNA-Seq fo, o)—differential profile—more in adult ovary than in fetal ovary. (b) CN loss overlapping with partial region of NR5A1 (26 kb; 9q33.3). UCSC Browser—CN loss (red) involving exon 1-intron 4 in a patient (Px D9; XY) with hypospadias (18 kb; 5 markers; chr9:127,261,935–127,279,829). DGV (Zarrei et al.,13)—no entry. ClinGen—UCS likely benign (LB) gain, pathogenic loss, UCS LP gain. DECIPHER—loss/gain (Note: truncated exon 1 of NR6A1 at the 3' end of the CNV). Segmental Dups (SegDups)—none. CpG Islands—intron 1-exon 2-intron 3. Protein Annotation (Prot Annot)—dimerization, ligand binding, phosphorylation, cross-linking, DNA binding, Zn finger, acetylation. Transcription Factor (Txn Factor)—exons 1-intron 4, upstream of NR5A1. WashU Epigenome Browser. Repeat Masker (Repeats)—exon 1-intron 4—SINEs (red), LINE (orange), LCRs (dark brown), SR/MS (gold); upstream of NR5A1—SINEs (red), LINE (orange), LCRs (dark brown), SR/MS (gold), DNA transposon (blue). ChromHMM—exon 1-intron 4, active transcription start site (aTSS) (red); enhancers (yellow), strong transcription site (green), weak TS (dark green); upstream of NR5A1—aTSS, enhancers, weak TS. Histone Modification—some H3K4me1 methylation and H3K27Ac acetylation marks in ovary. DNA Methylation (methylC-seq t, ov) in 5 regions involving NR5A1 (numbered and underlined)—absence of DNA methylation in fetal testes in exons 2–3 (1) and intron 1 (3) overlapping with an enhancer; absence of methylation in intron 1 overlapping with an aTSS in both fetal testis and ovary (2); absence of methylation in ovary in exon 1 (3) and upstream of NR5A1 overlapping with an enhancer (5). RNA Expression (RNA-Seq fo, o)—similar RNA expression in adult and fetal ovaries. Local Interactions (CCHiC-HFF1-M-R1/NS-R1)—various regions within and upstream of NR5A1 are locally interacting (purple). (c) CN gain involving intron 1 of CTNNB1 (41 kb, 3p22.1). UCSC Browser—CN gain (blue) overlapping with intron 1 of CTNNB1 in a patient (Px D14, XY) with ambiguous genitalia (12.6 kb, 59 markers; chr3:41243113–41255684). DGV (Zarrei et al.,13)—no overlapping CNVs found. ClinGen—no overlapping CNVs found. DECIPHER—losses in patients with variable findings. Segmental Dups (SegDups)—none. CpG Islands—none. Protein Annotation (Prot Annot)—none. Transcription Factor (Txn Factor)—several. WashU Epigenome Browser. Repeat Masker (Repeats)—LINEs (orange), SINEs (red), DNA transposons (blue). ChromHMM—active transcription start site (aTSS) (red); enhancers (yellow), weak TS (dark green). Histone Modification—some H3K4me1 methylation and H3K27Ac acetylation marks in ovary. DNA Methylation (methylC-seq t, ov)—differential DNA methylation in fetal testes and fetal ovaries. RNA Expression (RNA-Seq fo, o)—differential profile in adult and fetal ovaries. Local Interactions (CCHiC-HFF1-M-R1/NS-R1)—various regions within and upstream of NR5A1 are locally interacting (purple arcs). Interchromosomal Interactions (Interchrom inset)—interactions of intron 1 of CTNNB1 with other chromosome loci (purple lines; details in Supplementary Figure 2A). CNV, copy number variation; LCRs, low copy repeats; LINEs, long interspersed elements; SINEs, short interspersed elements.

Genomic and epigenomic landscape

Of the 301 CNVs overlapping with DSD genes, 36% (n=107) and approximately 60% (n=184) accounted for CNVs with exonic and intronic breakpoints, respectively. Thirteen exonic CNVs involved exon 1 of 9 genes (2.5–95.7 kb; 5–47 markers) (Supplementary Table S4), and 34 intronic CNVs involved intron 1 of 15 genes (1.2–29 kb; 3–95 markers) (Supplementary Table S5). Of the remaining non-exon/intron 1 CNVs (n=225/75%; 1.1–507 kb; 2–208 markers), 54% were losses and 36% involved exons (Supplementary Table S6). The majority of exon 1 CNVs (12/13) and the intron 1 of NR5A1 overlapped with functional regions coding for signal peptides, for integral membrane structures and for DNA or ligand binding, as well as with active transcription start sites with unmethylated or differentially methylated CGIs predicted to regulate differential gene expression in normal fetal testes and in fetal and adult ovaries (Figure 1a, b). Other regions upstream or downstream of a gene, within a gene or at its 3'-UTR were also found to include CGIs and other differentially methylated enhancers or active transcription start sites predicted to regulate spatiotemporally the expression of other cis/trans genes or regions25 (Figure 1c; Supplementary Figures S2A–D).

Segmental duplications and repeat elements

Segmental duplications (segdups) are low copy repeats prone to non-allelic homologous recombinations, often resulting in recurrent, large CNVs.20,26–30 These segdups were found in 16 genes that involved 108 CNVs, with segdups located in DMD and DHRSX showing the highest CNV frequencies (Supplementary Table S7). Smaller repeat elements have been exapted as binding sites for transcription factors, acting as alternative and differentially methylated promoters or enhancers31–33 dysregulating the host's gene expression machinery. Non-allelic homologous recombinations involving such repeats have also been described to result in recurrent but smaller deletions/duplications in various human genetic disorders.30,34,35 All of the CNVs detected in our study showed variable distribution of these smaller repeat elements: RNA repeats, AT-rich regions, simple repeats or microsatellites, DNA transposons and retroelements, such as long terminal repeats, short interspersed elements, including Alu and mammalian wide interspersed repeats, and long interspersed elements (Supplementary Table S7; Figure 1, Supplementary Figure S2). These intervals were also found to harbor CGIs, enhancers and active transcription start sites, which exhibit differential DNA methylation and histone modification, as well as predicting RNA expression in the normal testis or ovary.

Region of homozygosity (ROH)

SNP-based CMA could detect genomic copy neutral (CN=2) stretches of allelic homozygosity. This study detected a total of 3,421 ROHs, and approximately 10% (n=333) overlapped with 92 DSD genes (Table 2; Supplementary Tables S2 and S8). Chromosomes with the most ROHs involving DSD genes were 15, 12 and X (Supplementary Figure S1A). Recurrent ROHs were seen in 58% (n=53) of these genes, with PTPN11 showing the highest frequency (n=29 patients) (Table 2, Supplementary Figure S2). Of the ROHs overlapping with DSD genes (∼71% were small), 174 showed no corresponding CNVs (exclusively ROH) (n=174) (Supplementary Table S8). Interestingly, eight X-linked genes seen in nine XX patients with DSD and/or Turner stigmata were found to have copy-neutral ROHs (no CNV) (Supplementary Table S9).

Recently, small ROHs detected by CMA were characterized in 46,XX SRY-negative testicular DSD patients.17 These regions involved 27 genes and exhibited variable and smaller sizes (than the clinical cutoff, i.e., 5–10 Mb) ranging from 200 bp (upstream of ZWINT) to 634 kb (INPP4B, USP38). Comparing these reported regions with our data (Supplementary Table S10), 19 small ROHs (1–8 Mb; 207–2,647 markers) involving 10 genes were also found in 16 of our patients (XX, XY, sex chromosome anomaly). Six of these genes were smaller than 50 kb.

Position effect

We customized a “position effect” CMA track to detect gene-desert regions that regulated the expression of a gene at a nearby or distant locus,36–38 e.g., the upstream region of SOX9.16,39–41 Our study uncovered four recurrent and overlapping small CN losses (1.6–6 kb; 8–17 markers) approximately 1.2 Mb downstream of SOX9 in four patients (Supplementary Table S11). These intervals included DNA transposons (Charlie15A, MER103C), retroelements (Alu and mammalian wide interspersed repeats) and differentially methylated enhancers predicted to interact with other cis/trans regions (Supplementary Figure S2D). In addition to the SOX9 region, 86 CNVs and 44 ROHs involving 15 and 11 regions were also detected, respectively. The regions with the highest frequencies were SHH (n=11) for CNVs and LCT for ROHs (n=20). Approximately 52% of the CNVs that involved 15 regions were ⩽50 kb (2–81 markers). Although many of the genes regulated by these regions are expressed in adrenal, urogenital and reproductive structures, their functional impact on sex development has yet to be determined.

Imprinted genes

We investigated 34 genes known to be imprinted (list obtained from the GeneImprint database: http://www.geneimprint.com/) for ROHs and CNVs (Supplementary Table S12). Approximately 65% of such genes were ⩽50 kb. SNRPN is one of these genes, which has been implicated in Prader-Willi syndrome with or without DSD. Using an “imprinting CMA track,” 118 CNVs and 20 ROHs were found to involve 22 and 14 genes (paternal, maternal or isoform-independent), respectively. The CNVs ranged from 1.6 kb to 2.4 Mb (2–728 markers), 73% of which were ⩽50 kb. The ROHs ranged from 1 to 2.5 Mb (229–969 markers). GRB10 showed the highest CNV frequency (n=19 patients). Concurrent gain and loss were exhibited by some genes, including GRB10 (13 patients) and SNRPN (7 patients). These genes are expressed in the adrenal gland, as well as the urogenital and reproductive structures, and their contributions to DSDs remain to be explored.

Linked genes and gene interactions

We explored the chromosome distribution of DSD genes, and we found several adjacent genes with recurrent ROH or CN gains (Supplementary Table S13), e.g., HSD3B1/HSD3B2/NOTCH2 (1p11.2-p12; ROH) in three patients with hypospadias (H/E), FGF8/CYP17A1 (10q24.32-q24.33; ROH) in three patients also with H/E and NR0B1/DMD (Xp21.2; gain) in two patients with genital anomalies.

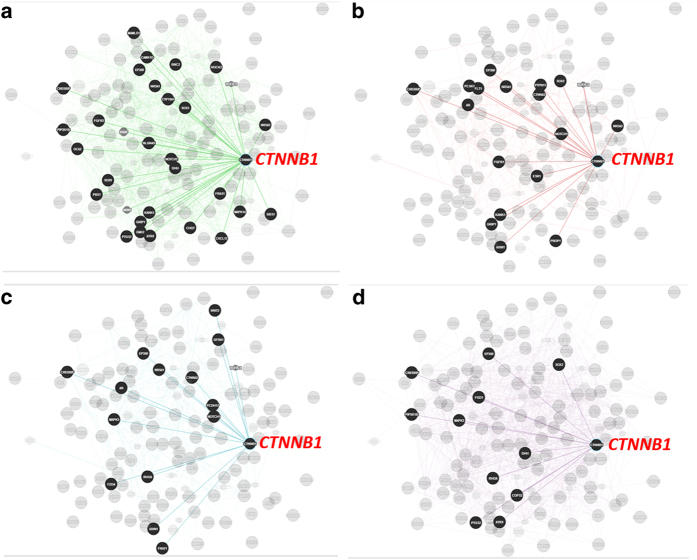

We utilized different public databases to investigate the interactions (e.g., genetic and physical) of the genes included in this study (Supplementary Table S14). Multiple interacting genes (DSD, imprinted, position) with CNVs and ROHs were revealed, with CTNNB1 showing the greatest number of interacting partners (Figure 2). Many other genes within the same pathway or network have also been found to exhibit local (cis) or interchromosomal (trans) gene interactions42 (Supplementary Table S14).

Figure 2.

Genetic (a) and physical (b) interactions, pathway associations (c) and co-expression (d) of CTNNB1 with other 125 genes (DSD, imprinted, position effect) with CNVs and ROH (GeneMANIA; http://www.genemania.org/). See Supplementary Table 24 for complete list of genes. CNV, copy number variation; DSD, disorders of sex development. Genes with predicted interactions/associations are in black circles, and without interaction/association are in gray circle.

Overlapping cases in DGV, ClinGen and DECIPHER

We compared our data with the most recent small CNV map (⩾ 50 bp; 2,057,368 variants) constructed from a normal cohort (n=2,647 subjects from 23 studies),13 and approximately 75% (225/301) of our CNVs were not overlapping (Supplementary Table S15; Figure 1a–c; Supplementary Figure S2D). We also searched the ClinGen database for comparable size CNVs overlapping with our data, and approximately 16% were documented as benign or likely benign, 7 CNVs (26–223 kb) involving 5 genes (CREBBP, CHD7, EP300, NR5A1, SUPT3H) were documented as pathogenic, and most (approximately 80%) showed no entry (Supplementary Table S15; Figure 1; Supplementary Figure S2). Approximately 61% of small CNVs that are common in healthy populations (DGV) or categorized as benign (ClinGen) were found to include salient genomic and epigenomic features characteristic of tissue-specific gene regulation and expression (Supplementary Tables S3, S4, S5, S6). The DECIPHER database also revealed CNVs with variable sizes overlapping with our data, and 19 DSD genes were documented to have small CNVs (33–50 kb), including CHD7, ANOS1 and WWOX, in patients with various DSD conditions (Supplementary Table S16). Although small ROHs (⩾ 4 kb) (Supplementary Table S17) overlapping with DSD genes and CNVs overlapping with position effect regions (⩾ 4.2 kb) (Supplementary Table S18) and imprinted genes (⩾ 1.8 kb) (Supplementary Table S19) were also documented in DECIPHER, none were reported in patients with DSD.

Small CNVs and ROHs correlated with DSD phenotype

Pathogenic CMA findings were reported originally in only 13% of patients, and all of the cases involved aneuploidy, polyploidy, mosaic sex chromosome complement or large structural anomalies (Table 1). Variants of uncertain clinical significance were reported in 23% of patients, none of which were recurrent. Normal CMA accounted for 62% of patients, approximately 12% of whom revealed ROHs in one or more chromosomes. CNVs and/or ROHs involving DSD genes were detected in all of the patients regardless of sex chromosome complement (XX, XY, aneuploid, mosaic) and original CMA finding (normal, pathogenic, variants of uncertain clinical significance).

Using our high-resolution and gene-targeted CMA approach, this retrospective study revealed individual genes with concurrent CNVs (loss/loss, gain/gain, loss/gain combinations) or multiple genes with concurrent CNVs and/or ROHs (Table 2). Some of these genes were found to be recurrent in two or more patients with similar DSD phenotypic findings (summarized in Supplementary Tables S20 and S21). The 28 patients with ambiguous genitalia with or without hypospadias/epispadias (H/E) revealed CNVs or ROHs involving 22 genes. All of the CNVs involving CXL12, VAMP7 and NOTCH1 were detected in seven patients with scrotal anomalies, undescended testes or micropenis/clitoromegaly, respectively. All of the ROHs involving AHRR and PTGDS were detected in four patients with undescended testes, while MAPK3 and NOTCH4 were seen in four patients with micropenis/clitoromegaly. All three patients with H/E revealed CNVs overlapping with a region known to regulate MAF (16q23.2) by position effect (Supplementary Table S11). Gains (71 kb; 21 markers) involving two imprinted linked genes (IGF2, IGF2AS on 11p15.5) were seen in two patients with H/E, undescended testes and micropenis/clitoromegaly, while ROHs (2.1 Mb; 297 markers) involving two imprinted, linked genes (BLCAP and NNAT at 20q11.23) were seen in two patients with ambiguous genitalia and H/E (Supplementary Table S12). The other DSD phenotypic findings were seen in a wide range of patients with variable CNV and ROH frequencies.

Discussion

Identification of small CNVs that include causative or candidate genes has recently been gaining more attention from genomics investigators. Large CNVs detected by CMA from cohorts of patients with similar phenotypic findings have been aligned to identify small regions of overlap that contain candidate genes.2,40,43–46 Data from genome sequencing have also been utilized to identify small CNVs.9,10,47,48 These studies have further demonstrated that, regardless of size, the clinical relevance of the detected CNV is determined by gene content and other layers of evidence.49,50 Current clinical CMA practice follows arbitrarily set limits such that CNVs smaller than these cutoffs are typically not analyzed or reported.

In this study, we uncovered small CNVs from unanalyzed CNVs previously obtained from DSD patients. Although relaxing our analysis filter to its 1 kb limit of detection generated an extensive list of variants, our customized DSD gene-targeted CMA track expeditiously filtered CNVs (with proportional probe coverage) overlapping with DSD genes, thereby allowing us to circumvent the daunting task of investigating all of the variants. The majority of the small CNVs detected in our investigations were not documented in comparable resources obtained from normal cohorts.13 Although the DECIPHER and ClinGen databases have documented overlapping CNVs, most of them were found to be relatively larger in size, and very few small CNVs were documented in patients with DSDs. These findings suggested that these variants are not common in healthy populations and remain underrepresented in clinical populations. Many deletions or duplications of partial regions of DSD genes have been described in various disorders, some of which were reported in DSDs (Supplementary Table S22). All of these findings, however, warrant further studies to determine whether these ‘rare’ CNVs are specific to either syndromic or isolated DSDs or to various clinical populations, including those at risk for gonadoblastoma or germ cell neoplasms and especially those CNVs involving genes implicated in cancer.

Our CMA approach demonstrated the ability to detect not only CNVs that are ⩽50 kb but also relevant genes that are smaller than the clinical CMA cutoff size. For example, small CN gains (4.9 and 5.6 kb) involving an intact small NR0B1 gene (approximately 5 kb in size) were detected in two patients with DSDs. These small CNVs and genes would be masked in clinical settings, unless it was one of the contiguous genes included within a reportable large CNV. We also identified not only potentially relevant private or overlapping small CNVs but also several CNVs that were recurrent in two or more patients with similar phenotypic findings. The breakpoints of these CNVs involved different regions or 5′ or 3′ ends, were intragenic or were upstream or downstream of a gene. High-resolution data obtained from this study provided us with a close-up view of the genomic details of deleted or duplicated structural and functional domains or regions. Although there are limited epigenomic data for the normal testis and ovary and none for atypical tissues, we were able to obtain DNA methylation, histone modification and RNA expression profiles in silico. Exon 1 CNVs exhibited the typical features of a 5′ promoter, such as the presence of unmethylated or differentially methylated CGIs,51 regulatory enhancers, active transcription start sites and regions coding for signal peptides. Intron CNVs were usually not reported in the past; however, their roles in various diseases have been gaining significance in recent years, e.g, disease-associated SNP variations were found in non-coding regions defined by regulatory H3K27Ac marks.52 The differential H3K27Ac marks52,53 and methylation and RNA expression profiles observed in some of the detected exon/intron 1 CNVs, as well as in other CNVs with orphan CGIs and enhancers acting as remote or cryptic promoter regions, suggested tight spatiotemporal testis/ovary-specific gene regulation.25 Importantly, we found that most of the CNVs involved genes that are highly expressed in adrenal, urogenital and other specific reproductive structures, which are key effector or recipient sites responsible for DSD phenotypes. In addition, these CNVs occur in genes that perform critical functions in sex development, including germ cell migration and development and gonadal and genital development, and in androgen and other signaling pathways. Whether CNVs or ROHs involving these regions and genes in these affected tissues would significantly result in improper peptide transport, aberrant protein structure, dysregulation of expression and ultimately a DSD phenotype remains to be elucidated.

Exaptation of transposable elements into promoter or enhancer regions has been correlated with spatiotemporal or tissue-specific gene regulation of the host genome.31,32,34,35,54 Our study focused on some of these elements within these small CNVs. Similar to segdups, these elements have been known to result in recurrent or overlapping small CNVs via non-allelic homologous recombination, and they have been implicated in various human disorders, e.g., the GTF2IRD1 and GTF2I genes distal to the ELN (7q11.23) locus that harbor DNA transposon CHARLIE-like region in Williams syndrome.30 Short interspersed elements are non-long terminal retroelements that are typically found in GC and gene-rich, early replicating euchromatin, as well as in cytogenetic G-banded light bands.31,55,56 It has been demonstrated that CNVs involving clusters of Alu short interspersed elements35 dysregulate gene expression within the promoter regions, they alter splicing and they shift reading frames, resulting in aberrant phenotypic findings.34,57 Although CNVs with or without differential methylation patterns for these DNA transposons and other repeats have been implicated in several human disorders,54,58–60 the significance of the repeat element-harboring CNVs that also showed regulatory genomic and epigenomic profiles remains to be pursued in DSDs.

An ROH region is typically reported in clinical settings if it is ⩾5 Mb and harbors a causative gene. However, regardless of how large the detected ROH interval is, such regions are further investigated for genes that might be inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern or involved in a disorder associated with uniparental disomy or imprinting. If detected, reflex studies, such as methylation or microsatellite analysis, are performed on the gene of interest. Our findings from gene-targeted approaches demonstrated that causative genes within an ROH less than the cutoff size could easily be revealed. Although copy neutral ROHs have been described in many neoplastic conditions,61 they are yet to be investigated in DSD. In a recent CMA study in patients with 46,XX testicular DSD, small ROH-harboring candidate DSD genes were uncovered.17 Similarly, our study revealed small CNVs and ROHs overlapping with some of the genes previously reported, as well as with DSD genes and imprinted genes. Although it has yet to be determined whether the CNVs and ROHs involving these genes would result in DSDs, our data provided several avenues for further investigations in DSD patients, including those at risk for gonadoblastoma or germ cell neoplasms.

Our CMA track specific for position effect regions easily detected small CNVs and/or ROHs in gene-desert regions. SOX9 is one of the genes that is regulated by upstream regulatory elements via position effect, and disruption of this region results in craniofacial, skeletal and sex development anomalies.39,41,62,63. On the basis of several reported cases, a more refined interval upstream of SOX9 was described as the smallest critical region for XX (68 kb) and XY (32.5 kb) DSDs.16,39,40 The recurrent, small deletions detected downstream of SOX9 in our DSD patients overlapped with the reported 1.3 Mb position effect region described in a patient with campomelic dysplasia (with DSD).62 Whether the much smaller CNVs overlapping with position effect regions that we revealed in this study would result in DSDs through mechanisms similar to SOX9 remains to be elucidated. It is also possible that the other genes mapped within the interval downstream of SOX9 contribute to the DSD phenotype (or not at all), although this relationship also remains to be investigated.

Mapping the relative distributions of CNVs and ROHs overlapping with DSD genes revealed that CNVs were mostly frequently observed on chromosomes X, 16 and 9, and ROHs were commonly found on chromosomes 15, 12 and X. Neither CNVs nor ROHs were observed on chromosomes 21 or Y. Some of these CNVs involve dose-sensitive haploinsufficient genes that typically exhibit highly conserved coding and promoter regions, and they are tissue-specific and embryonically expressed. These genes are known to interact strongly with other haploinsufficiency genes in the same network.24 As genomic tools have become more sophisticated, more combinations of variants obtained from CMA and/or sequencing, both common and rare, have been revealed, e.g., compound heterozygote, triploinsufficiency and CNV/SNV combination, and some have been implicated in human diseases. Whether CNVs or ROHs involving DSD genes (including linked, imprinted or position effect genes) that are within the DSD network result in pathway dysregulation and subsequently in isolated or syndromic DSDs remains to be elucidated and mapped. The chromosome distribution of DSD genes and their associated CNVs and ROHs, as well as their local and interchromosomal interactions, could provide a better picture of the genomic landscape and perhaps of some of the tools needed to draw the genomic and epigenomic maps of the spatiotemporal regulation of interactions, pathways and networks in DSDs.

Our retrospective CMA identified recurrent small CNVs and ROHs overlapping with DSD genes in patients with sex chromosome aneuploidy or mosaicism, variants of uncertain clinical significance and clinically normal CMA. These findings emphasized our gene-targeted and disease-specific CMA approach to identifying small CNVs overlapping with genes or small regions of overlap that might be relevant to DSDs, supporting this approach in improving the diagnostic power and utility of CMA. In addition, these findings provided shorter intervals for detailed genomic and epigenomic analyses. The results obtained from this study will contribute significantly to the accumulating resources for small CNVs, as well as in narrowing the genomic gap in both normal and clinical populations. We are encouraged that this study will provide many avenues for downstream genomic and epigenomic research investigations and that our DSD-specific CMA approach will advance our understanding regarding DSDs, as well as provide a model analysis tool for finding small CNVs in other human disorders.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Washington University in St Louis School of Medicine (WUSTL SoM) DSD Clinic and Research team and Mike Evenson and Jennifer Stamm-Birk of Cytogenomics Lab (WUSTL SOM) for assisting in initial patient data gathering. We also thank Amy Dodson and Dr Ma Xenia Ilagan (WUSTL SOM), Dr Julius Militante and Dr Christian Nievera for their helpful comments on the manuscript.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information for this article can be found on the Human Genome Variation website (http://www.nature.com/hgv).

References

- Iafrate AJ , Feuk L , Rivera MN , Listewnik ML , Donahoe PK , Qi Y et al. Detection of large-scale variation in the human genome. Nat Genet 2004; 36: 949–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper GM , Coe BP , Girirajan S , Rosenfeld JA , Vu TH , Baker C et al. A copy number variation morbidity map of developmental delay. Nat Genet 2011; 43: 838–846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook EH Jr. , Scherer SW . Copy-number variations associated with neuropsychiatric conditions. Nature 2008; 455: 919–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao Y , Tyson C , Hrynchak M , Lopez-Rangel E , Hildebrand J , Martell S et al. Clinical application of 2.7 M Cytogenetics array for CNV detection in subjects with idiopathic autism and/or intellectual disability. Clin Genet 2013; 83: 145–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Cid R , Riveira-Munoz E , Zeeuwen PL , Robarge J , Liao W , Dannhauser EN et al. Deletion of the late cornified envelope LCE3B and LCE3C genes as a susceptibility factor for psoriasis. Nat Genet 2009; 41: 211–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarroll SA , Huett A , Kuballa P , Chilewski SD , Landry A , Goyette P et al. Deletion polymorphism upstream of IRGM associated with altered IRGM expression and Crohn's disease. Nat Genet 2008; 40: 1107–1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad A , Merico D , Thiruvahindrapuram B , Wei J , Lionel AC , Sato D et al. A discovery resource of rare copy number variations in individuals with autism spectrum disorder. G3 (Bethesda) 2012; 2: 1665–1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glessner JT , Bick AG , Ito K , Homsy JG , Rodriguez-Murillo L , Fromer M et al. Increased frequency of de novo copy number variants in congenital heart disease by integrative analysis of single nucleotide polymorphism array and exome sequence data. Circ Res 2014; 115: 884–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poultney CS , Goldberg AP , Drapeau E , Kou Y , Harony-Nicolas H , Kajiwara Y et al. Identification of small exonic CNV from whole-exome sequence data and application to autism spectrum disorder. Am J Hum Genet 2013; 93: 607–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krumm N , O'Roak BJ , Karakoc E , Mohajeri K , Nelson B , Vives L et al. Transmission disequilibrium of small CNVs in simplex autism. Am J Hum Genet 2013; 93: 595–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad DF , Pinto D , Redon R , Feuk L , Gokcumen O , Zhang Y et al. Origins and functional impact of copy number variation in the human genome. Nature 2010; 464: 704–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uddin M , Thiruvahindrapuram B , Walker S , Wang Z , Hu P , Lamoureux S et al. A high-resolution copy-number variation resource for clinical and population genetics. Genet Med 2015; 17: 747–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarrei M , MacDonald JR , Merico D , Scherer SW . A copy number variation map of the human genome. Nat Rev Genet 2015; 16: 172–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes IA , Houk C , Ahmed SF , Lee PA Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society/European Society for Paediatric Endocrinology Consensus, G. Consensus statement on management of intersex disorders. J Pediatr Urol 2006; 2: 148–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee PA , Houk CP , Ahmed SF , Hughes IA. International Consensus Conference on Intersex organized by the Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine, S. and the European Society for Paediatric, E. Consensus statement on management of intersex disorders. International Consensus Conference on Intersex. Pediatrics 2006; 118: e488–e500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kon M , Fukami M . Submicroscopic copy-number variations associated with 46,XY disorders of sex development. Mol Cell Pediatr 2015; 2: 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno K , Kojima Y , Kamisawa H , Moritoki Y , Nishio H , Nakane A et al. Elucidation of distinctive genomic DNA structures in patients with 46,XX testicular disorders of sex development using genome wide analyses. J Urol 2014; 192: 535–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norling A , Linden Hirschberg A , Iwarsson E , Persson B , Wedell A , Barbaro M . Novel candidate genes for 46,XY gonadal dysgenesis identified by a customized 1 M array-CGH platform. Eur J Med Genet 2013; 56: 661–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White S , Ohnesorg T , Notini A , Roeszler K , Hewitt J , Daggag H et al. Copy number variation in patients with disorders of sex development due to 46,XY gonadal dysgenesis. PLoS One 2011; 6: e17793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tannour-Louet M , Han S , Corbett ST , Louet JF , Yatsenko S , Meyers L et al. Identification of de novo copy number variants associated with human disorders of sexual development. PLoS ONE 2010; 5: e15392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost RJ , Hamra FK , Richardson JA , Qi X , Bassel-Duby R , Olson EN . MOV10L1 is necessary for protection of spermatocytes against retrotransposons by Piwi-interacting RNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010; 107: 11847–11852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firth HV , Richards SM , Bevan AP , Clayton S , Corpas M , Rajan D et al. DECIPHER: database of Chromosomal Imbalance and Phenotype in Humans Using Ensembl Resources. Am J Hum Genet 2009; 84: 524–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X , Maricque B , Xie M , Li D , Sundaram V , Martin EA et al. The Human Epigenome Browser at Washington University. Nat Methods 2011; 8: 989–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang N , Lee I , Marcotte EM , Hurles ME . Characterising and predicting haploinsufficiency in the human genome. PLoS Genet 2010; 6: e1001154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczyk MS , Hughes JR , Garrick D , Lynch MD , Sharpe JA , Sloane-Stanley JA et al. Intragenic enhancers act as alternative promoters. Mol Cell 2012; 45: 447–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mignon-Ravix C , Depetris D , Luciani JJ , Cuoco C , Krajewska-Walasek M , Missirian C et al. Recurrent rearrangements in the proximal 15q11-q14 region: a new breakpoint cluster specific to unbalanced translocations. Eur J Hum Genet 2007; 15: 432–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez L , Nevado J , Santos F , Heine-Suner D , Martinez-Glez V , Garcia-Minaur S et al. A deletion and a duplication in distal 22q11.2 deletion syndrome region. Clinical implications and review. BMC Med Genet 2009; 10: 48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber JC , Hall V , Maloney VK , Huang S , Roberts AM , Brady AF et al. 16p11.2-p12.2 duplication syndrome; a genomic condition differentiated from euchromatic variation of 16p11.2. Eur J Hum Genet 2013; 21: 182–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt T , Blanchard L , Desai K , Nimkarn S , Cohen N , Edelmann L et al. 46,XY disorder of sex development and developmental delay associated with a novel 9q33.3 microdeletion encompassing NR5A1. Eur J Med Genet 2013; 56: 619–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai L , Bellugi U , Chen XN , Pulst-Korenberg AM , Jarvinen-Pasley A , Tirosh-Wagner T et al. Is it Williams syndrome? GTF2IRD1 implicated in visual-spatial construction and GTF2I in sociability revealed by high resolution arrays. Am J Med Genet A 2009; 149A: 302–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jjingo D , Conley AB , Wang J , Marino-Ramirez L , Lunyak VV , Jordan IK . Mammalian-wide interspersed repeat. MIR)-derived enhancers and the regulation of human gene expression. Mob DNA 2014; 5: 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Souza FS , Franchini LF , Rubinstein M . Exaptation of transposable elements into novel cis-regulatory elements: is the evidence always strong? Mol Biol Evol 2013; 30: 1239–1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekram MB , Kim J . High-throughput targeted repeat element bisulfite sequencing. (HT-TREBS): genome-wide DNA methylation analysis of IAP LTR retrotransposon. PLoS ONE 2014; 9: e101683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belancio VP , Deininger PL , Roy-Engel AM . LINE dancing in the human genome: transposable elements and disease. Genome Med 2009; 1: 97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deininger PL , Batzer MA . Alu repeats and human disease. Mol Genet Metab 1999; 67: 183–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia S , Kleinjan DA . Disruption of long-range gene regulation in human genetic disease: a kaleidoscope of general principles, diverse mechanisms and unique phenotypic consequences. Hum Genet 2014; 133: 815–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinjan DA , Lettice LA . Long-range gene control and genetic disease. Adv Genet 2008; 61: 339–388, (07)00013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinjan DA , van Heyningen V . Long-range control of gene expression: emerging mechanisms and disruption in disease. Am J Hum Genet 2005; 76: 8–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyon C , Chantot-Bastaraud S , Harbuz R , Bhouri R , Perrot N , Peycelon M et al. Refining the regulatory region upstream of SOX9 associated with 46,XX testicular disorders of Sex Development. DSD. Am J Med Genet A 2015; 167: 1851–1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim GJ , Sock E , Buchberger A , Just W , Denzer F , Hoepffner W et al. Copy number variation of two separate regulatory regions upstream of SOX9 causes isolated 46,XY or 46,XX disorder of sex development. J Med Genet 2015; 52: 240–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amarillo IE , Dipple KM , Quintero-Rivera F . Familial microdeletion of 17q24.3 upstream of SOX9 is associated with isolated Pierre Robin sequence due to position effect. Am J Med Genet A 2013; 161A: 1167–1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rios O , Frias S , Rodriguez A , Kofman S , Merchant H , Torres L et al. A Boolean network model of human gonadal sex determination. Theor Biol Med Model 2015; 12: 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girirajan S , Dennis MY , Baker C , Malig M , Coe BP , Campbell CD et al. Refinement and discovery of new hotspots of copy-number variation associated with autism spectrum disorder. Am J Hum Genet 2013; 92: 221–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asadollahi R , Oneda B , Joset P , Azzarello-Burri S , Bartholdi D , Steindl K et al. The clinical significance of small copy number variants in neurodevelopmental disorders. J Med Genet 2014; 51: 677–688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piard J , Mignot B , Arbez-Gindre F , Aubert D , Morel Y , Roze V et al. Severe sex differentiation disorder in a boy with a 3.8 Mb 10q25.3-q26.12 microdeletion encompassing EMX2. Am J Med Genet A 2014; 164A: 2618–2622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Materna-Kiryluk A , Kiryluk K , Burgess KE , Bieleninik A , Sanna-Cherchi S , Gharavi AG et al. The emerging role of genomics in the diagnosis and workup of congenital urinary tract defects: a novel deletion syndrome on chromosome 3q13.31-22.1. Pediatr Nephrol 2014; 29: 257–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan R , Wang Y , Kleinstein SE , Liu Y , Zhu X , Guo H et al. An evaluation of copy number variation detection tools from whole-exome sequencing data. Hum Mutat 2014; 35: 899–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coe BP , Witherspoon K , Rosenfeld JA , van Bon BW , Vulto-van Silfhout AT , Bosco P et al. Refining analyses of copy number variation identifies specific genes associated with developmental delay. Nat Genet 2014; 46: 1063–1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacArthur DG , Manolio TA , Dimmock DP , Rehm HL , Shendure J , Abecasis GR et al. Guidelines for investigating causality of sequence variants in human disease. Nature 2014; 508: 469–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearney HM , Thorland EC , Brown KK , Quintero-Rivera F , South ST Working Group of the American College of Medical Genetics Laboratory Quality Assurance, C. American College of Medical Genetics standards and guidelines for interpretation and reporting of postnatal constitutional copy number variants. Genet Med 2011; 13: 680–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guenther MG , Levine SS , Boyer LA , Jaenisch R , Young RA . A chromatin landmark and transcription initiation at most promoters in human cells. Cell 2007; 130: 77–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hnisz D , Abraham BJ , Lee TI , Lau A , Saint-Andre V , Sigova AA et al. Super-enhancers in the control of cell identity and disease. Cell 2013; 155: 934–947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consortium EP . An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature 2012; 489: 57–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotkin RK , Martienssen R . Transposable elements and the epigenetic regulation of the genome. Nat Rev Genet 2007; 8: 272–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander ES , Linton LM , Birren B , Nusbaum C , Zody MC , Baldwin J et al. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature 2001; 409: 860–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niimura Y , Gojobori T . In silico chromosome staining: reconstruction of Giemsa bands from the whole human genome sequence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2002; 99: 797–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callinan PA , Batzer MA . Retrotransposable elements and human disease. Genome Dyn 2006; 1: 104–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B , Xing X , Li J , Lowdon RF , Zhou Y , Lin N et al. Comparative DNA methylome analysis of endometrial carcinoma reveals complex and distinct deregulation of cancer promoters and enhancers. BMC Genomics 2014; 15: 868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T , Zeng J , Lowe CB , Sellers RG , Salama SR , Yang M et al. Species-specific endogenous retroviruses shape the transcriptional network of the human tumor suppressor protein p53. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007; 104: 18613–18618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi Z , Garrison N , Cohen-Barak O , Karafet TM , King RA , Erickson RP et al. A 122.5-kilobase deletion of the P gene underlies the high prevalence of oculocutaneous albinism type 2 in the Navajo population. Am J Hum Genet 2003; 72: 62–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar Y , Yang J , Hu T , Chen L , Xu Z , Xu L et al. Massive interstitial copy-neutral loss-of-heterozygosity as evidence for cancer being a disease of the DNA-damage response. BMC Med Genomics 2015; 8: 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velagaleti GV , Bien-Willner GA , Northup JK , Lockhart LH , Hawkins JC , Jalal SM et al. Position effects due to chromosome breakpoints that map approximately 900 Kb upstream and approximately 1.3 Mb downstream of SOX9 in two patients with campomelic dysplasia. Am J Hum Genet 2005; 76: 652–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox JJ , Willatt L , Homfray T , Woods CG . A SOX9 duplication and familial 46,XX developmental testicular disorder. N Engl J Med 2011; 364: 91–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.