Abstract

Angiomyolipoma (AML) of the liver is a very uncommon lipomatous neoplasm, usually asymptomatic and incidentally identified. We describe the imaging findings of a histologically confirmed case using different modalities (US, CT, and MRI). We review and correlate current literature with our imaging and histological findings.

Case report

A 63-year-old woman was admitted with an exacerbation of longstanding upper-abdominal pain associated with nausea, vomiting, and rigors. Upper GI endoscopy revealed a small hiatus hernia, and abdominal ultrasound (US) was performed to assess for clinically suspected gallstones. This revealed a well-defined hyperechoic lesion in the liver (Fig. 1), considered to be unrelated to presenting symptoms.

Figure 1.

63-year-old female with AML. Transabdominal ultrasound of the liver shows a hyperechoic lesion in the liver (arrow).

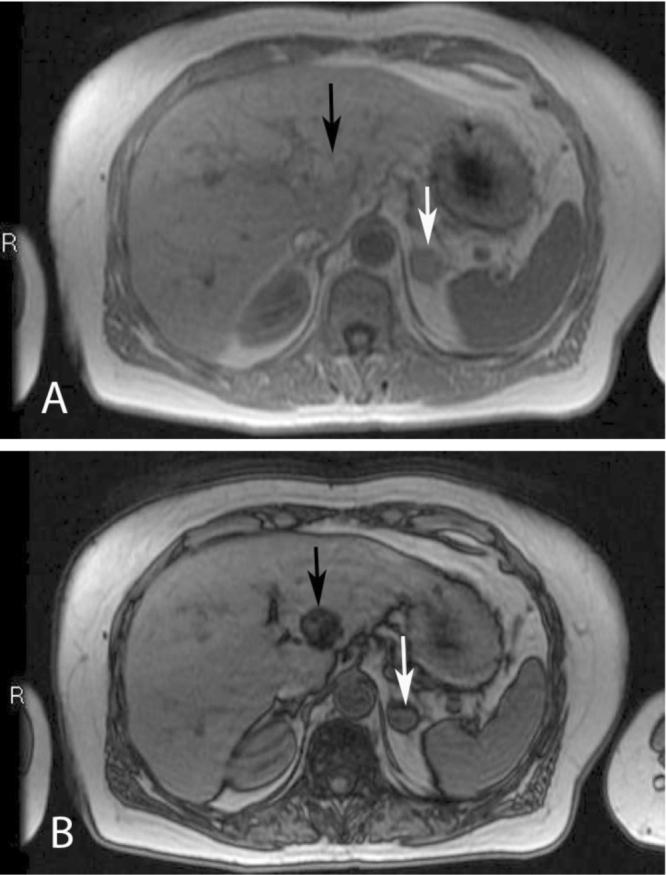

The patient then underwent additional investigations in the form of multiphase computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to further evaluate the liver abnormality. On the precontrast CT images (Fig. 2), the lesion was of low attenuation, with an average of −26 Hounsfield units (HU), suggestive of fat. The lesion also demonstrated contrast enhancement on the postcontrast arterial phase (Fig. 3) and early washout on the portal venous phase (Fig. 4). The MRI scan confirmed the presence of intralesional fat, which was best demonstrated with in- and out-of-phase T1-weighted gradient imaging (Fig. 5). The postcontrast MRI images also demonstrated an enhancement pattern similar to that seen by CT.

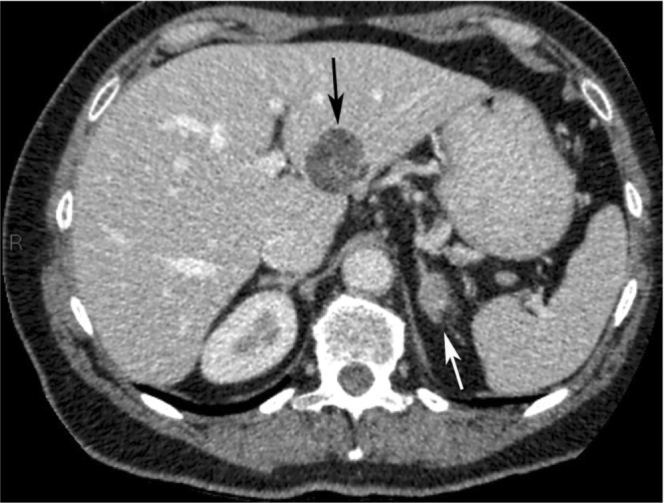

Figure 2.

63-year-old female with AML. Axial precontrast CT of abdomen shows a low-attenuation liver lesion (black arrow) with an average of −26 HU. The left adrenal gland demonstrates a 1.7-cm nodule (white arrow) with an average of 14 HU.

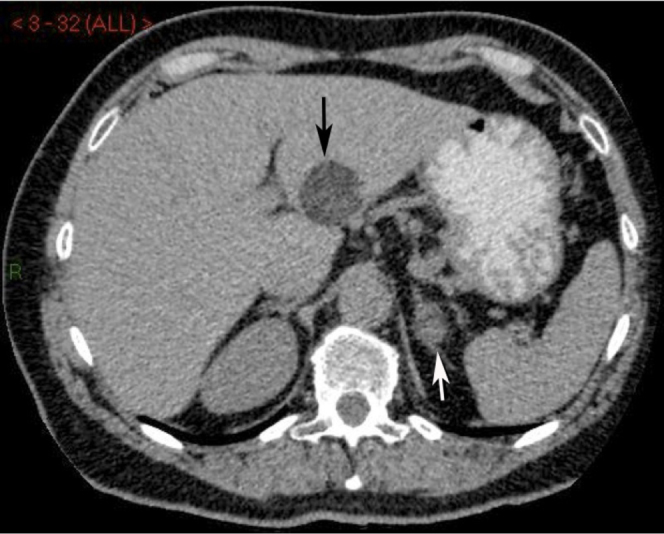

Figure 3.

63-year-old female with AML. Axial postcontrast CT of abdomen in the arterial phase shows heterogeneous contrast enhancement of the liver lesion (black arrow). The left adrenal lesion (white arrow) enhances to 40 HU.

Figure 4.

63-year-old female with AML. Axial postcontrast CT of abdomen in the portal venous phase shows contrast washout from the liver lesion (black arrow). The left adrenal lesion (white arrow) enhances to 70 HU. Based on CT characteristics, including the delayed CT images (not shown), the left adrenal lesion is thought to represent a benign adenoma.

Figure 5.

63-year-old female with AML. Axial MRI of abdomen, In-phase (A) and out-of-phase (B) gradient images show signal dropout, confirming the presence of fat in the liver lesion (black arrows). In addition, the images show some fat content within the left adrenal lesion (white arrows) with signal dropout anteriorly and on the right, suggestive of an adenoma.

Due to the uncertainty of the diagnosis, the patient underwent laparoscopic surgical resection of the lesion. Histology showed an epitheloid tumor containing a combination of smooth muscle, fat, and blood vessels (Fig. 6). The tumor cells stained positive for HMB-45 (monoclonal antibody specific for human melanosomes). Accordingly, a diagnosis of AML was made.

Figure 6.

63-year-old female with AML. Histology specimen shows features of AML with the characteristic combination of smooth muscle, fat, and blood vessels.

Discussion

Angiomyolipoma is a rare benign tumor (1). It is commonly found in the kidney, but is rarely found in the liver (2). It was first described by Ishak in 1976, and a few cases of hepatic AML have since been reported in the literature (3). AML has occasionally been found in other organs including the uterus, retroperitoneum, mediastinum, renal capsule, nasopharyngeal cavity, buccal mucosa, penis, vagina, abdominal wall, skin, and spinal cord (2). As with the renal variety, hepatic AML is associated with tuberous sclerosis (4).

AML is a hamartomatous lesion of mesenchymal origin. The precursor cell is believed to be the PEC (perivascular epitheloid cell), and as such has been labeled a PEComa (5). Histologically, AML is characterized by a mixture of mature fat cells, blood vessels, and smooth muscle cells in various proportions. Hematopoietic cells may also be present. HMB-45 staining is diagnostic of hepatic AML, as seen in this case, as no other primary hepatic tumors stain positive for this (5).

Radiologically, AML can be diagnosed by demonstrating both fatty and vascular components within the lesion. However, differentiating AML from other fatty lesions of the liver remains difficult (5). On ultrasound, AML appears as a well-defined, hyperechoic lesion with good through-transmission, although larger lesions tend to have a more mixed echogenicity pattern (6, 7). AML cannot be differentiated from hemangioma or hyperechoic metastasis on US; both of them are more common than AML. Hemangioma, like AML, is usually an incidental finding that does not give rise to symptoms. More specific features are usually obtained by CT. AML is distinguished by the presence of low-attenuation (less than −20 HU) areas corresponding to fat. However, there have been many reports of AML with minimal fat content not detectable by CT. On contrast-enhanced CT, AML tends to show enhancement by 20 to 30 HU. Strong enhancement in the arterial phase reflects the presence of large intralesional vessels, a common finding in larger AML. Rapid contrast washout is commonly seen on the portal venous phase (5). The key point in the diagnosis of AML is to confirm the presence of intralesional fat, which is best demonstrated with in- and out-of-phase T1-weighted gradient imaging (7). Complications such as tumor hemorrhage can also be seen on MRI (7).

According to the relevant literature, hepatic AML can be diagnosed pre-operatively based on the following findings: i) Hypervascular nature on imaging, suggesting vascular proliferation within the tumor. ii) Intralesional fat on CT, MRI, and US. iii) Positive actin and HMB-45 stains on biopsy specimen, which proves smooth muscle component (8). In our case, surgery could have potentially been avoided if the correct diagnosis had been made pre-operatively. Although the combination of US, CT, MRI, and occasionally angiography increases the accuracy in diagnosis of hepatic AML, the correct preoperative diagnostic rate of imaging studies has been reported to be less than 50% (3, 9, 10).

Preoperative identification of AML is desirable because of differences in clinical course and treatment between this disease and other hepatic neoplasms. The key imaging finding of AML in all organs is intralesional fat, although the differential diagnosis of a fat-containing liver lesion is wide. In these cases, the possibility of hepatic AML, although rare, should be considered.

Footnotes

Published: May 15, 2013

References

- 1.Zhong DR, Ji XL. Hepatic angiomyolipoma-misdiagnosis as hepatocellular carcinoma: A report of 14 cases. World J Gastroentero. 2000;6(4):608–612. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i4.608. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Romano F, Franciosi C, Bovo G, Cesana GC, Isella G, Colombo G. Case report of a hepatic angiomyolipoma. Tumori. 2004;90:139–143. doi: 10.1177/030089160409000128. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang CY, Ho MC, Jeng YM, Hu RH, Wu YM, Lee PH. Management of hepatic angiomyolipoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:452–457. doi: 10.1007/s11605-006-0037-3. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang B, Chen WH, Li QY, Xiang JJ, Xu RJ. Hepatic angiomyolipoma: dynamic computed tomography features and clinical correlation. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(27):3417–3420. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3417. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hawxby AM, Torbenson M, Fishman E, Lawler L, Arrazola LM, Klein AS. Juxta-caval hepatic angiomyolipoma masquerading as hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2003;2:617–621. [PubMed] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ren N, Qin LX, Tang ZY, Wu ZQ, Fan J. Diagnosis and treatment of hepatic angiomyolipoma in 26 cases. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:1856–1858. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i8.1856. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chatziioannou A, Karvouni E, Koutoulidis V, Smirniotis B, Mourikis D, Katsenis K. Vlachos. Angiomyo(myelo)lipoma of the liver: typical imaging findings and review of the literature. European J of Radiol Extra. 2003;46:110–115. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zheng R, Kudo M. Hepatic angiomyolipoma: identification of an efferent vessel to be hepatic vein by contrast-enhanced harmonic ultrasound. Br J Radiol. 2005;78:956–960. doi: 10.1259/bjr/27365821. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balci NC, Akinci A, Akun E, Tunaci A. Hepatic angiomyolipoma. Demonstration by out of phase MRI. Clin Imaging. 2002;26:418–420. doi: 10.1016/s0899-7071(02)00509-0. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yan F, Zeng M, Zhou K, Shi W, Zheng W, Da R. Hepatic angiomyolipoma: various appearances on two-phase contrast scanning of spiral CT. Eur J Radiol. 2002;41:12–18. doi: 10.1016/s0720-048x(01)00392-8. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]