Abstract

Hedgehog (Hh) signaling controls embryonic development and adult tissue homeostasis through the G protein coupled receptor (GPCR)-family protein Smoothened (Smo). Upon stimulation, Smo accumulates on the cell surface in Drosophila or primary cilia in vertebrates, which is thought to be essential for its activation and function, but the underlying mechanisms remain poorly understood. Here we show that Hh stimulates the binding of Smo to a plasma membrane-associated kinase Gilgamesh (Gish)/CK1γ and that Gish fine-tunes Hh pathway activity by phosphorylating a Ser/Thr cluster (CL-II) in the juxtamembrane region of Smo carboxyl-terminal intracellular tail (C-tail). We find that CL-II phosphorylation is promoted by protein kinase A (PKA)-mediated phosphorylation of Smo C-tail and depends on cell surface localization of both Gish and Smo. Consistent with CL-II being critical for high-threshold Hh target gene expression, its phosphorylation appears to require higher levels of Hh or longer exposure to the same level of Hh than PKA-site phosphorylation on Smo. Furthermore, we find that vertebrate CK1γ is localized at the primary cilium to promote Smo phosphorylation and Sonic hedgehog (Shh) pathway activation. Our study reveals a conserved mechanism whereby Hh induces a change in Smo subcellular localization to promote its association with and activation by a plasma membrane localized kinase, and provides new insight into how Hh morphogen progressively activates Smo.

A study of both fruit flies and vertebrate cells shows that the plasma membrane-associated kinase Gish/CK1γ promotes transduction of the Hedgehog signal by phosphorylating Smoothened.

Author Summary

The secreted glycoprotein Hedgehog (Hh) plays a conserved role in embryonic development and adult tissue homeostasis in species ranging from Drosophila to humans. Deregulation of Hh signal transduction contributes to a wide range of human disorders, including birth defects and cancer. The seven-transmembrane protein Smoothened (Smo) is an obligatory and conserved Hh signal transducer, but how Hh stimulates its activity remains unclear. Here we identify a plasma membrane associated kinase, Gilgamesh (Gish)/CK1γ, as a positive regulator of the Hh signaling activity. We find that Gish activates Hh signaling by phosphorylating a specific site in the Smo C-terminal intracellular tail. Phosphorylation of Smo by Gish is required for maximal activation of Smo and depends on membrane association of Gish and prior phosphorylation of Smo by protein kinase A (PKA). We also find that Hh stimulates the association of Smo with Gish after it travels to the plasma membrane, thus facilitating its phosphorylation by Gish. Finally, we provide evidence that CK1γ is found at the primary cilium in mammals and phosphorylates Smo to activate the Hh pathway. Our results uncover a conserved role of Gish/CK1γ in the regulation of Smo phosphorylation and provide new insight into the molecular underpinning of how Hh signal is transduced across the plasma membrane.

Introduction

Hedgehog (Hh) signaling plays an essential role in embryonic development and adult tissue homeostasis, and its deregulation has been implicated in congenital diseases and cancers [1–6]. Hh exerts its biological influence through an intracellular signal transduction cascade that emanates from a G protein coupled receptor (GPCR)-family protein Smoothened (Smo) and culminates in the activation of the latent transcription factor Cubitus interruptus (Ci)/Glioma-associated oncogene homologue (Gli) [1,3,7,8]. In the signaling off state, Smo is inhibited by a twelve-transmembrane protein Patched (Ptc). Binding of Hh to Ptc alleviates such inhibition, allowing Smo to be phosphorylated and accumulate on the cell surface in Drosophila or primary cilia in vertebrates, where Smo adopts an open and active conformation to relay the Hh signal to the intracellular signaling components [9–15].

Phosphorylation plays a critical role in the regulation of Smo conformation and subcellular localization [16]. In Drosophila, unphosphorylated or hypophosphorylated Smo adopts a closed, inactive conformation [12] and is ubiquitinated and removed from the cell surface by both proteasome- and lysosome-mediated degradation [17,18]. Upon Hh stimulation, Smo is phosphorylated by protein kinase A (PKA) and casein kinase 1 (CK1), mainly the CK1α/ε isoforms, at three clusters of Ser/Thr residues in its carboxyl-terminal intracellular tail (C-tail) [19–22], which drives a conformational switch of Smo C-tail from the closed inactive to an open active conformation, leading to dimerization/oligomerization of the C-tail [12]. In addition, PKA/CK1α/ε-mediated phosphorylation inhibits ubiquitination of Smo, leading to its cell surface accumulation and activation [17,18]. In addition to PKA and CK1α/ε, Smo activity is also modulated by casein kinase 2 (CK2), atypical protein kinase C (aPKC), and G protein coupled receptor kinase 2 (Gprk2) [23–26]. Gprk2 promotes Smo activity by directly binding and phosphorylating the Smo C-tail to stabilize its active conformation [24]. In mammals, Hh-stimulated phosphorylation of Smo by CK1α and Gprk2 promotes its ciliary localization and active conformation [15]. Cell surface/ciliary accumulation of Smo is thought to be essential for its activation and function [14,27]; however, the underlying mechanism is still poorly understood.

Hh functions as a morphogen to specify different developmental outcomes in a concentration-dependent manner [1,3]. As such, Hh signal transduction needs to be tightly controlled to achieve pathway activities appropriate with the ligand inputs. Although the characterized phosphorylation events contribute to Smo activation, they do not represent all the activation mechanisms, as phospho-mimetic mutations failed to fully activate Smo in both Drosophila and mammals [15,19,24], suggesting that additional mechanisms, either phosphorylation-dependent or independent, may exist. Indeed, Drosophila Smo is phosphorylated at more than 26 Serine (Ser)/Threonine (Thr) residues, many of which have not been well characterized [20].

CK1γ, which is encoded by gilgamesh (gish) in Drosophila [28], is a membrane-associated Ser/Thr kinase of the CK1 family [29]. Gish/CK1γ has been implicated in the regulation of Wingless (Wg)/Wnt signaling by phosphorylating the co-receptor Arrow (Arr)/LRP5/6 [30,31]. Gish is also involved in glial cell migration in Drosophila eye [28], olfactory learning [32], and planar cell polarity (PCP)-mediated morphogenesis [33]. Mammals have three CK1γ isoforms encoded by different genes [29], making it difficult to study the role of CK1γ in development. In this study, we identified Gish as a positive regulator of Hh signaling through a genetic modifier screen. We demonstrated that Hh stimulates the association between Gish and Smo in a manner depending on cell surface localization of both Gish and Smo as well as PKA-mediated phosphorylation of Smo C-tail. We provided evidence that Gish phosphorylates a membrane proximal region of Smo C-tail to promote high levels of Hh pathway activity. However, loss of Gish only caused a minor defect in Hh pathway activity, likely due to a redundancy with another kinase(s). We also found that vertebrate CK1γ is localized at primary cilia depending on its membrane association, and that CK1γ promotes Smo phosphorylation and Sonic hedgehog (Shh) pathway activation depending on the primary cilia. Our results suggest that plasma membrane/ciliary-localized CK1γ plays a conserved role in Hh signaling by promoting the maximal levels of Smo activity.

Results

A Genetic Modifier Screen Identified Gish as a Positive Regulator of the Hh Pathway

To identify additional Hh pathway regulators, we have conducted an RNAi-based genetic modifier screen to identify enhancers or suppressors of a "fused wing" phenotype caused by expression of a dominant negative Smo (Smo-PKA12/SmoDN) with a wing-specific Gal4 drivers MS1096 (MS>SmoDN) [19,24,25]. We found that expressing a UAS-RNAi line (V106826) targeting Gish, the Drosophila homologue of mammalian CK1γ, enhanced the “fused wing” phenotype caused by MS>SmoDN (Fig 1A–1C). Using immunostaining with a Gish antibody, we found that Gish RNAi effectively knocked down Gish protein expression in wing imaginal discs (S1A–S1B' Fig). Moreover, two additional UAS-GishRNAi lines, V26003 and BL28066, enhanced the MS>SmoDN-induced phenotype in a similar fashion (S1C–S1F Fig). On the other hand, overexpression of a wild-type Gish, but not a kinase dead form (GishKD), partially suppressed the “fused wing” phenotype caused by MS>SmoDN (Fig 1D and 1E and S1K and S1L Fig).

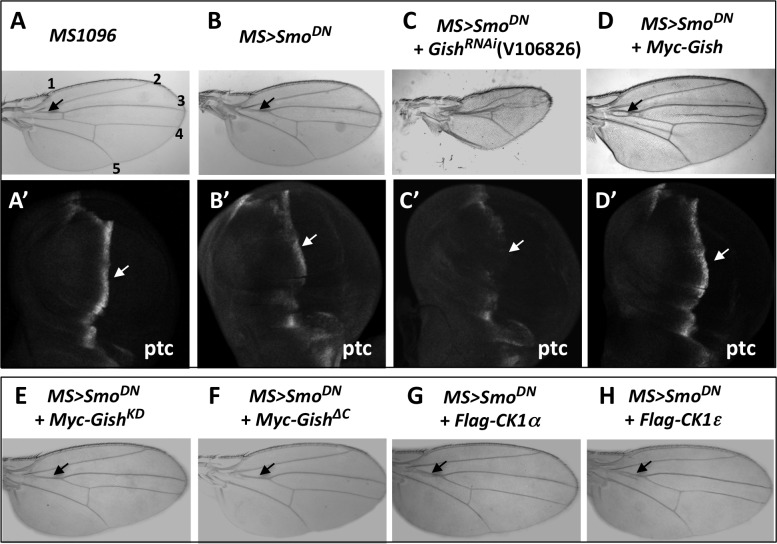

Fig 1. Gish positively regulates Hh signaling.

(A–H) Control wing (A) or wings expressing a dominant negative Smo using MS1096 (MS>SmoDN) either alone (B) or together with UAS-Gish-RNAi (C), UAS-Myc-Gish (D), UAS-Myc-GishKD (E), UAS-GishΔC (F), UAS-Flag-CK1α (G), or UAS-Flag-CK1ε (H). MS>SmoDN caused a fusion between veins 3 and 4 (arrow in B), which was enhanced by Gish RNAi (C) but partially suppressed by Gish overexpression (arrow in D). Overexpression of GishKD, GishΔC, CK1α, or CK1ε failed to suppress the “fused wing” phenotype caused by MS>SmoDN. (A'-D') Late third instar wing discs of the indicated genotypes immunostained with an anti-Ptc antibody. MS>SmoDN diminished ptc expression near the A/P boundary (arrow in B'). Gish RNAi further reduced while Gish overexpression restored ptc expression (arrows in C', D'). In this and the following figures, images are representatives of five or more adult wings or wing discs for each genotype.

Gish/CK1γ is localized to the plasma membrane due to its C-terminal palmitoylation [30,33]. Interestingly, overexpression of a soluble form of Gish with its palmitoylation site deleted, GishΔC [33], failed to rescue MS>SmoDN-induced wing phenotype, even though it was expressed at levels similar to the wild-type Gish (Fig 1F and S1M Fig compared with S1K Fig), suggesting that plasma membrane association of Gish is critical for its function in this context. Consistent with this notion, overexpression of other soluble CK1 family members, including CK1α and CK1ε, also failed to rescue the MS>SmoDN phenotype (Fig 1G and 1H).

To determine whether loss- or gain-of-Gish function modified the "fused wing" phenotype through the Hh pathway, we examined the expression of an Hh target gene ptc. In control late third instar wing imaginal discs, Hh induced ptc expression in A-compartment cells near the A/P boundary (Fig 1A'). In MS>SmoDN wing discs, ptc expression near the A/P boundary was greatly reduced (Fig 1B'). Gish RNAi in MS>SmoDN wing discs nearly abolished ptc expression near the A/P boundary in the wing pouch region where MS1096 was expressed (Fig 1C'). On the other hand, overexpression of Gish restored ptc expression close to wild-type levels (Fig 1D'). Hence, gain- or loss-of-Gish activity can modulate Hh pathway activity.

To determine where Gish acts in the Hh pathway, we examined its genetic interaction with Fused (Fu), a Ser/Thr kinase acting downstream of Smo [11,34,35]. Inactivation of Fu by expressing a USA-RNAi transgene with MS1096 (MS>FuRNAi) caused a similar "fused wing" phenotype, albeit more severe than that caused by MS>SmoDN (S1H Fig). However, neither Gish overexpression nor RNAi modified the wing phenotype caused by MS>FuRNAi (S1I and S1J Fig), suggesting that Gish may act upstream of Fu in the Hh pathway.

Characterization of gish Mutants

To confirm the Gish RNAi phenotype, we turned to gish mutants. gishKG03891 is a P-element insertion mutation and a strong allele of gish [32], which is referred to as gishP hereafter. Although gishP heterozygosity did not modify the fused wing phenotype caused by MS>SmoDN (Fig 2B compared with Fig 2A), MS>SmoDN wings carrying gishP homozygous clones exhibited a greatly enhanced phenotype similar to that caused by Gish RNAi in MS>SmoDN wings (Fig 2C compared with Fig 1C and S1E and S1F Fig). Interestingly, we found that heterozygosity for gish deficiency, Df(3R)ED10639 (BL#9481), also enhanced the fused wing phenotype caused by MS>SmoDN (Fig 2D), suggesting that gishP is not a null allele. To obtain a gish null allele, we generated imprecise excision lines from gishP and found several lines including gishΔ4 that could enhance the MS>SmoDN phenotype similarly to gishDf (Fig 2E). Consistent with gishΔ4 being a null allele, gishΔ4 mutant clones in wing discs exhibited diminished Gish immunostaining (S2A and S2B Fig). Furthermore, the enhancement of the MS>SmoDN phenotype by gishΔ4/+ was reversed by coexpression of the wild-type Gish but not by coexpression of either GishKD or GishΔC (Fig 2F–2H).

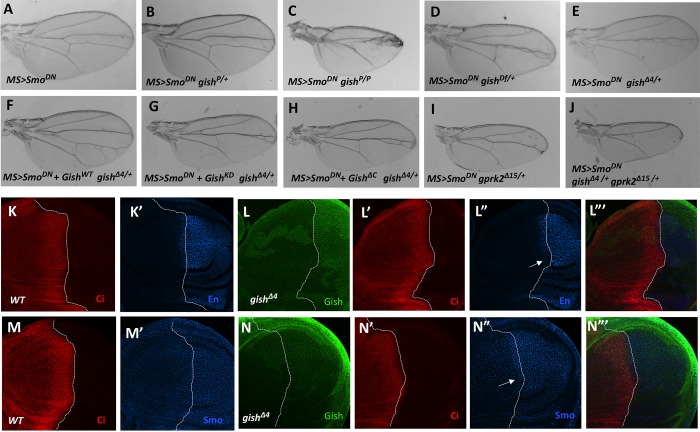

Fig 2. gish is required for high levels of Hh pathway activity and genetically interacts with gprk2.

(A–J) Adult wings of the indicated genotypes. MS>SmoDN caused a fusion between veins 3 and 4 (A). MS>SmoDN wing carrying gishP clones exhibited an enhanced phenotype (C). Heterozygosity for gishDf (D) or gishΔ4 (E) but not gishP (B) enhanced the fused wing phenotype caused by MS>SmoDN. Overexpression of wild-type Gish (F) but not GishKD (G) or GishΔC (H) rescued the fused wing phenotype caused by MS>SmoDN in gish heterozygous background. Heterozygosity for gprk2Δ15 also enhanced the MS>SmoDN phenotype (I). gprk2Δ15 and gishΔ4 double heterozygosity enhanced the MS>SmoDN phenotype more dramatically than either gprk2Δ15 or gishΔ4 single heterozygosity (J compared with E and H). (K–N‴) Late third instar wild type wing discs (K, K', M, M') or wing discs carrying gishΔ4 mutant clones induced at 24–48 h after egg laying (AEL) (L–L‴, N–N'') were immunostained to show the expression of Ci (red), Gish (green), En (blue in K', L", L‴), or Smo (blue in M', N", N‴). gishΔ4 mutant cells abutting the A/P boundary (demarcated by dashed lines) exhibited reduced En and Smo staining (arrows in L", N").

Our previous study identified Gprk2 as a positive regulator of Hh signaling in a similar genetic modifier screen [24]. Heterozygosity of a gprk2 null allele, gprk2Δ15, also enhanced the fused wing phenotype caused by MS>SmoDN (Fig 2I). Interestingly, taking away one copy of gish in this background (MS>SmoDN gish Δ4/+ gprk2 Δ15/+) further enhanced the wing phenotype (Fig 2J). This dosage-sensitive genetic interaction between Gish and Gprk2 suggests that they may act in close proximity in the Hh signaling pathway.

Gish Is Required for High-Level Hh Pathway Activity

We then induced gishΔ4 clones using the MARCM system [36] at 24–48 h or 48–72 h after egg laying (AEL). gishΔ4 clones (marked by green fluorescent protein [GFP] expression) induced at 48–72 h AEL survived to late third instar larval stages but did not affect the expression of Hh target genes ptc and engrailed (en) when localized in A-compartment cells near the A/P boundary (S2D–S2D" Fig and Fig 2F–2F" compared with S2C–S2C" and S2E–S2E" Fig). gishΔ4 clones induced at 24–48 h AEL were barely recovered, suggesting that gish mutant cells had a growth disadvantage and were competed out by wild-type cells over time. To recover early-induced clones, we generated gishΔ4 clones in a Minute background, which gave gish mutant cells a growth advantage [37]. As shown in Fig 2 and S2 Fig, gishΔ4 clones (marked by the lack of Gish staining) induced at 24–48 h AEL in the Minute background occupied large areas in late third instar wing discs (Fig 2L and 2N, S2H Fig). ptc expression, which is induced by intermediate levels of Hh, was not affected in gishΔ4 clones (S2H" and S2H‴ Fig); however, en expression in A-compartment cells near the A/P boundary, which is induced by peak levels of Hh, was diminished in gishΔ4 clones (arrow in Fig 2L–2L‴). In addition, Hh-induced Smo accumulation appeared to be attenuated in gishΔ4 clones (arrow in Fig 2N–2N‴). These results suggest that Gish is required for high levels of Hh signaling activity and may regulate the Hh pathway at the level of Smo.

Gish Phosphorylates the Membrane Proximal Region of Smo C-tail

A previous study revealed that Smo derived from Hh-stimulated S2 cells was phosphorylated at 26 Ser/Thr residues in its C-tail, including the three PKA/CK1 phosphorylation clusters and Gprk2 sites (Fig 3A) [20]. However, the kinases responsible for phosphorylating other sites, most notably, a membrane proximal cluster (CL-II) of Ser/Thr residues, 623DlNSSETNDISS634 (underlined S/T residues were phosphorylated sites detected by Mass Spec) [20], have not been identified (Fig 3A). A close inspection of the CL-II site indicates that it contains Ser/Thr residues falling into the consensus sites for the CK1 family kinases: D/E/(p)S/T(X)1-3S/T, in which the underlined S/T is the CK1 site, whereas X represents any amino acid [29]. Indeed, a Glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion protein containing the intact (GST-Smo601-700) but not the mutated CL-II site (GST-Smo601-700 CL-II SA) was phosphorylated by a recombinant CK1 in an in vitro kinase assay (Fig 3B). To determine whether CL-II is phosphorylated by Gish, we transfected S2 cells with a Smo construct, Myc-Smo△C650, which contains the CL-II site but lacks distal phosphorylation sites such as the PKA/CK1 phosphorylation clusters and Gprk2 sites. We found that Hh stimulation induced a mobility shift of Myc-Smo△C650, which is indicative of Smo phosphorylation [19], and that Hh-induced mobility shift of Myc-Smo△C650 was diminished by Gish RNAi (Fig 3C). Coexpression of Myc-Smo△C650 with Gish also induced a mobility shift of Myc-Smo△C650 (Fig 3C and 3D). Furthermore, mutating the CL-II site in Myc-Smo△C650 (Myc-Smo△C650CL-IISA) abolished its mobility shift induced by either Hh stimulation or Gish overexpression (Fig 3D). Taken together, these results suggest that Hh induces phosphorylation of CL-II through Gish.

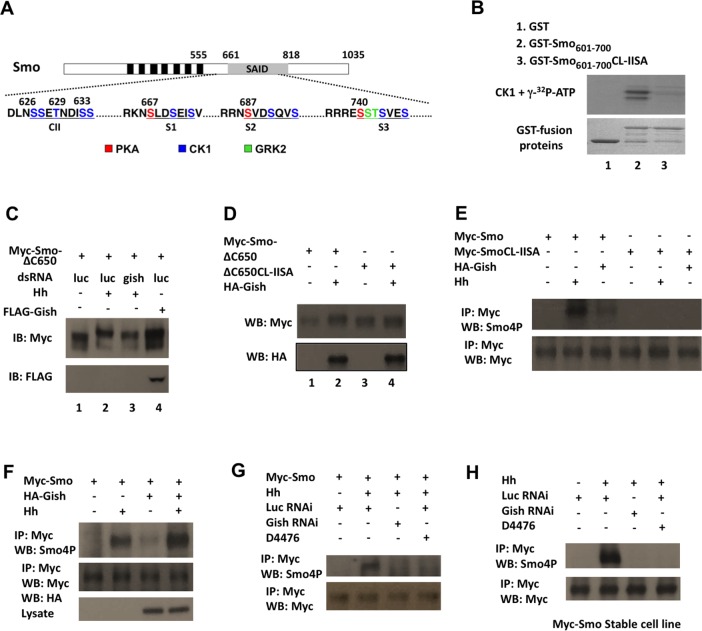

Fig 3. Hh promotes CL-II phosphorylation through Gish.

(A) Diagram of Smo with PKA, CK1, and Gprk2 sites indicated by different colors. Black and gray boxes denote the seven transmembrane domains and the Smo auto-inhibited domain (SAID), respectively. (B) In vitro kinase assay using recombinant CK1 and GST-Smo fusion proteins carrying wild-type (GST-Smo601-700) or mutated CL-II site (GST-Smo601-700CL-IISA). (C, D) Western blots of lysates from S2 cells transfected with the indicated constructs, treated with or without the indicated dsRNA and Hh-conditioned medium. (E, F, L) Western blots of immunoprecipitation experiments from lysates of S2 cells transfected with the indicated constructs. Cells were grown in the presence or absence of Hh stimulation for 24 h and exposed to MG132 (50 μM) for 4 h before harvest. (G, H) S2 cells transiently (G) or stably (H) expressing Myc-Smo were treated with control RNAi, Gish RNAi, or D4476. Cells were grown in the presence or absence of Hh stimulation for 24 h and exposed to MG132 (50 μM) for 4 h, followed by immunoprecipitation and western blot analysis.

Hh Stimulates CL-II Phosphorylation by Plasma Membrane-Associated Gish

To characterize CL-II phosphorylation in the context of full-length Smo, we generated a phospho-specific antibody named Smo4P using the phospho-peptide NDLN(PS)(PS)E(PT)NDI(PS)STW as an antigen (see Materials and Methods). Western blot analysis indicated that purified Smo4P antibody recognized GST-Smo601-700 but not GST-Smo601-700CL-llSA after in vitro phosphorylation by CK1. We found that Smo4P recognized Myc-Smo but not Myc-SmoCL-llSA derived from S2 cells stimulated with Hh or coexpressing Flag-Gish (Fig 3E and 3F). Overexpression of Gish further increased the Hh-stimulated Smo4P signal (Fig 3F). To further demonstrate that Hh stimulates CL-II phosphorylation through Gish, we examined the phosphorylation state of Myc-Smo derived from transiently transfected S2 cells or a stably expressing cell line treated with control or Gish dsRNA and stimulated with Hh. We found that Gish RNAi abolished Hh-stimulated Smo4P signal associated with Myc-Smo (Fig 3G and 3H). A recent study argued that Gprk2 is responsible for CL-II phosphorylation [38]; however, we found that Gprk2 RNAi or overexpression did not affect Smo4P signal intensity associated with Myc-Smo (S3A and S3B Fig). Furthermore, treatment of Myc-Smo-expressing cells with a pharmacological CK1 inhibitor, D4476, also abolished Hh-stimulated Smo4P signal (Fig 3G and 3H). These results suggest that Hh stimulates CL-II phosphorylation through Gish rather than Gprk2.

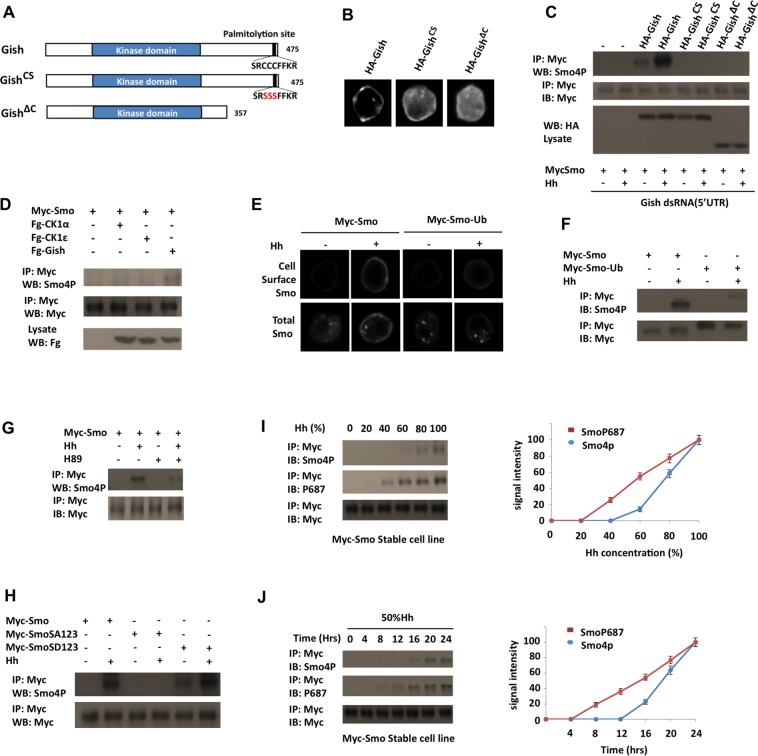

Gish/CK1γ is attached to the inner leaf of the plasma membrane through its C-terminal palmitoylation (Fig 4A) [30]. Indeed, HA-Gish was mainly associated with cell membrane when expressed in S2 cells (Fig 4B). By contrast, HA-GishCS and HA-GishΔC, which have their C-terminal palmitoylation signal (SRCCCFFKR) substituted (SRSSSFFKR) or deleted, respectively (Fig 4A), exhibited cytoplasmic distribution (Fig 4B) [33]. We then coexpressed HA-Gish, HA-GishCS, or HA-GishΔC with Myc-Smo in S2 cells with endogenous Gish knocked down by dsRNA targeting the 5' UTR of gish. Western blot analysis with Smo4P indicated that only the membrane-associated form of Gish (HA-Gish) but not the cytosolic variants (HA-GishCS and HA-GishΔC) could support CL-II phosphorylation in response to Hh (Fig 4C), suggesting that plasma membrane association of Gish is critical for CL-II phosphorylation. In addition, we found that coexpression of the cytosolic CK1 family members CK1α and CK1ε with Myc-Smo did not significantly increase the Smo4P signal in either the presence or absence of Hh stimulation (Fig 4D and S3C Fig). These results may explain why overexpression of wild-type Gish but not GishΔC, CK1α, or CK1ε could partially rescue the wing phenotype caused by MS-SmoDN (Fig 1D and 1F–1H).

Fig 4. CL-II phosphorylation depends on PKA and cell surface localization of both Smo and Gish.

(A) Diagrams of wild-type Gish and its mutant derivatives. (B) Immunostaining of S2 cells transfected with the indicated Gish constructs. (C) Western blots of immunoprecipitation experiments from lysates of S2 cells treated with dsRNA targeting the gish 5’ UTR and transfected with Myc-Smo together with the indicated Gish constructs. Cells were grown in the presence or absence of Hh stimulation for 24 h and exposed to MG132 (50 μM) for 4 h before harvest. (E, F) S2 cells were transfected with Myc-Smo or Myc-Smo-Ub and stimulated with or without Hh, followed by immunostaining to visualize cell surface Smo (top panels in E) or total Smo (bottom panels in E), or by immunoprecipitation and western blot analysis with the indicated antibodies. (G) S2 cells stably expressing Myc-Smo were treated with or without Hh-conditioned medium and H89 and exposed to MG132 (50 μM) for 4 h, followed by immunoprecipitation and western blot analysis by the indicated antibodies. (H) Western blots of immunoprecipitation experiments from lysates of S2 cells transfected in indicated Smo constructs. Cells were grown in the presence or absence of Hh stimulation for 24 h and exposed to MG132 (50 μM) for 4 h before harvest. (I, J) S2 cells stably expressing Myc-Smo were treated with different levels of Hh or the same level of Hh for different periods of time, followed by immunoprecipitation and western blot analysis by the indicated antibodies. Quantification of Smo4P and P687 signals is shown to the right. The signal intensities at 100% Hh or 24 h are defined as 100. Data are means ± SD from three independent experiments.

CL-II Phosphorylation Depends on Cell Surface Localization of Smo

To determine whether cell surface localization of Smo is important for CL-II phosphorylation, we employed a Myc-tagged Smo variant that has a ubiquitin (Ub) moiety fused to its C-terminus (Myc-Smo-Ub) [18]. We confirmed the previous finding that Myc-Smo-Ub failed to accumulate on the cell surface in response to Hh (Fig 4E) [18,39]. However, Myc-Smo-Ub could still be phosphorylated by PKA and accumulate on the cell surface in response to PKA phosphorylation (S4 Fig), suggesting that adding the Ub moiety to the Smo C-terminus did not cause an overall structure change of Smo C-tail to preclude its phosphorylation by any kinase. We then determined whether failure to accumulate on the cell surface affected Hh-induced phosphorylation of Smo at the CL-II site. As shown in Fig 4F, Hh-induced Smo4P signal associated with Myc-Smo-Ub was dramatically reduced compared to that associated with Myc-Smo. This result suggests that cell surface localization of Smo is critical for its phosphorylation by Gish.

CL-II Phosphorylation Depends on PKA-Mediated Phosphorylation of Smo

Previous studies suggest that Hh stimulates Smo phosphorylation by PKA and CK1α/ε at three clusters of Ser/Thr residues in the middle region of Smo C-tail (Fig 3A), and that these phosphorylation events promote Smo cell surface accumulation and conformational change [12,19]. To determine whether PKA-mediated phosphorylation of the distal sites regulates Gish-mediated phosphorylation of the membrane proximal sites, we first treated Myc-Smo expressing cells with a pharmacological PKA inhibitor H89 and found that inhibition of PKA activity diminished the Hh-stimulated Smo4P signal associated with Myc-Smo (Fig 4G). We then compared CL-II phosphorylation of a PKA-phosphorylation deficient (Myc-SmoSA123) or a phospho-mimetic (Myc-SmoSD123) form of Smo with that of wild-type Myc-Smo [19]. We found that Hh failed to stimulate the Smo4P signal associated with Myc-SmoSA123 (Fig 4H). On the other hand, Myc-SmoSD123 exhibited enhanced basal Smo4P signal, which was further enhanced upon Hh stimulation (Fig 4H). Taken together, these results suggest that PKA/CK1-mediated phosphorylation of Smo in the distal region facilitates Gish-mediated phosphorylation of the juxtamembrane region of Smo C-tail.

Differential Regulation of CL-II and PKA Site Phosphorylation by Hh

We next determined whether PKA site phosphorylation and CL-II phosphorylation were induced by different levels of Hh. S2 cells stably expressing Myc-Smo were treated with Hh-conditioned medium containing different levels of Hh-N (20%, 40%, 60%, 80%, or 100%) for 4 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc antibody, followed by western blot analysis with either anti-SmoP687, which recognized the phosphorylated PKA site (S687) as well as two downstream CK1 sites [40], or anti-Smo4P. As shown in Fig 4I, SmoP687 signal began to be detected at 40% Hh, whereas Smo4P signal was detected only when the Hh levels exceeded 60% Hh. Myc-Smo expressing S2 cells were also treated with 50% Hh for different periods of time (4, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 24 h). SmoP687 signal began to be detected 8 h after Hh stimulation, whereas Smo4P was not detected until 16 h after Hh stimulation (Fig 4J). Hence, the CL-II phosphorylation appears to require higher levels of Hh or longer exposure to the same level of Hh than the PKA-site phosphorylation.

CL-II Phosphorylation Is Required for Optimal Smo Activity

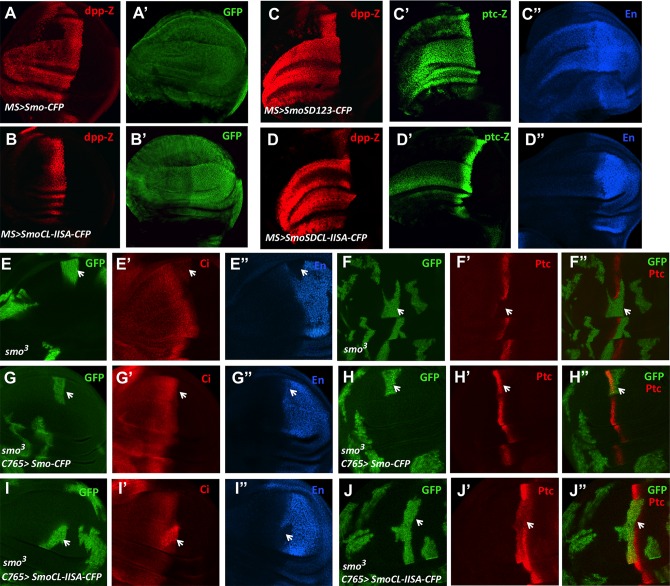

To determine the functional importance of CL-II phosphorylation, we mutated CL-II in the context of Smo-cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) or SmoSD123-CFP to generate SmoCL-IISA-CFP and SmoSDCL-IISA-CFP, respectively (see Materials and Methods). Consistent with previous findings [11,19], overexpression of Smo-CFP using the MS1096 Gal4 driver (MS>Smo-CFP) induced ectopic expression of dpp-lacZ, which is a low-threshold Hh target gene (Fig 5A); however, SmoCL-IISA-CFP failed to induce ectopic dpp-lacZ expression (Fig 5B). While MS>SmoSD123-CFP induced ectopic expression of not only dpp-lacZ but also ptc-lacZ and en at high levels (Fig 5C–5C"), SmoSDCL-IISA-CFP failed to induce ectopic expression of en and only induced ectopic expression of ptc-lacZ at low levels, although the ectopic expression of dpp-lacZ was not affected by the CL-IISA mutation (Fig 5D–5D"). Hence, mutating the CL-II site in Smo compromised its ability to activate the Hh pathway. Coexpression of Flag-Gish with Smo-CFP increased the ectopic dpp-lacZ expression, leading to more dramatic overgrowth of the wing discs (S5A and S5B' Fig). By contrast, coexpression of Flag-Gish with SmoCL-IISA-CFP did not alter its activity (S5C and S5D' Fig), consistent with the notion that Gish promotes Hh signaling activity through phosphorylating the CL-II site.

Fig 5. CL-II phosphorylation is required for optimal Smo activation.

(A–D") Wing discs expressing MS>Smo-CFP (A–A′), MS>SmoCL-IISA-CFP (B, B’), MS>SmoSD123-CFP (C–C") or MS>SmoSDCL-IISA-CFP (D–D") were immunostained to show the expression of dpp-lacZ, GFP, ptc-lacZ or En. (E–J") Wing discs carrying smo3 MACRM clones in the absence (E–F") or presence of C765>Smo-CFP (G–H") or C765>SmoSDCL-IISA-CFP (I–J") were immunostained to show the expression of GFP, Ci, Ptc, and En. Arrows indicate smo3 clones (marked by GFP) near the A/P boundary.

To discern the in vivo function of CL-II phosphorylation more precisely, we expressed Smo-CFP and SmoCL-IISA-CFP at low levels using the weak Gal4 driver C765 (C765>Smo) in wing discs carrying smo3 mutant clones. Our previous study revealed that the levels of Smo derived from C765>Smo were only slightly higher than that of endogenous Smo [22]. We found that C765>Smo-CFP completely rescued the expression of both ptc and en in smo3 mutant clones located near the A/P boundary (Fig 5G–5H" compared with Fig 5E–5F"). By contrast, C765>SmoCL-IISA-CFP failed to rescue en expression and only partially rescued ptc expression in smo3 clones (Fig 5I–5J"). In addition, A/P boundary-located smo3 cells expressing C765>SmoCL-IISA-CFP accumulated high levels of full-length Ci (Fig 5I'), suggesting SmoCL-IISA-CFP could still inhibit Ci processing but fail to induce the maturation of full-length Ci into the active but labile form [41]. Furthermore, we found that SmoCL-IISA-CFP, like Smo-CFP, promoted Ci nuclear localization in smo mutant clones (S5E–S5F′′′ Fig). Previous studies revealed that Ci nuclear translocation occurs in A-compartment cells more than ten cells away from the A/P boundary, where there are low levels of Hh [42,43]. Collectively, these results demonstrate that CL-II phosphorylation is essential for Smo to transduce high levels of Hh signaling activity but is dispensable for low levels of Hh pathway activity.

Gish- and Gprk2-Mediated Phosphorylation Promotes High Levels of Smo Activity

Our previous study demonstrated that Gprk2 promotes high levels of Hh pathway activity by regulating the active state of Smo through both kinase activity dependent and independent mechanisms [24]. Gprk2 phosphorylated Smo at Ser741/Thr742 and S1013/S1015, and mutating these sites (GPSA12) in the context of SmoSD123 (SmoSDGPSA) compromised Hh pathway activity [24]. However, expression of a Smo variant with the Gprk2 sites mutated (SmoGPSA) using the strong Gal4 driver MS1096 fully rescued the expression of Hh target genes including ptc and en in A/P boundary-located smo3 clones. We reasoned that overexpression of SmoGPSA to levels much higher than the physiological level could mask its signaling defect. Indeed, expression of SmoGPSA with C765 only rescued ptc expression but failed to restore en expression in A/P boundary-located smo3 clones (S6A–S6B′′ Fig). Hence, Grpk2-mediated phosphorylation of Smo is also required for its optimal activity.

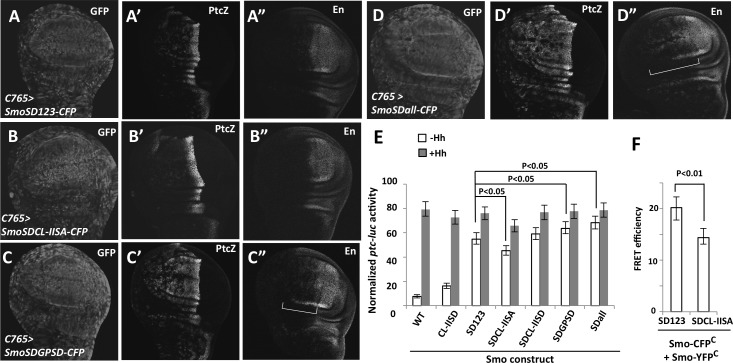

To further determine the contribution of Gish- and Gprk2-mediated phosphorylation of Smo to Hh pathway activation and how differential Smo phosphorylation generates degraded Hh pathway activity, we introduced phospho-mimetic mutations to the CL-II site (CL-IISD) in the context of SmoSDGPSD, which contains phospho-mimetic mutations in the three PKA/CK1 phosphorylation clusters (SD123) and two Gprk2 sites (GPSD) [24], to generate SmoSDall. Hence, SmoSDall represents Smo with the highest level of phosphorylation, followed by SmoSDGPSD, SmoSD123, and SmoSDCL-IISA. When expressed in wing discs using C765, SmoSD123 induced ectopic ptc-lacZ expression in A-compartment cells both distant from and close to the A/P boundary, albeit at levels lower than that of endogenous ptc-lacZ at the A/P boundary (Fig 6A and 6A'). In addition, SmoSD123 induced weak ectopic en expression in A-compartment cells near the A/P boundary (Fig 6A"). SmoSDCL-IISA induced ectopic ptc-lacZ expression at lower levels than SmoSD123 and failed to induce any ectopic en expression (Fig 6B–6B"), consistent with its activity being weaker than SmoSD123. Similar to SmoSDCL-IISA, SmoSDGPSA also exhibited weaker activity than SmoSD123 because it only induced low levels of ectopic ptc expression but failed to induce ectopic en expression (S6C–S6D′′ Fig). On the other hand, SmoSDGPSD and SmoSDall induced ectopic expression of ptc-lacZ and en at higher levels than SmoSD123 (Fig 6C–6D"). Although both SmoSDall and SmoSDGPSD induced ectopic ptc-lacZ expression at similar levels (Fig 6C' and 6D'), SmoSDall induced ectopic en expression in more anterior cells than SmoSDGPSD (Fig 6C" and 6D"). We also examined the activity of several Smo variants with different phospho-mimetic mutations in Clone 8 (Cl8) cells through a ptc-luciferase reporter assay. As shown in Fig 6E, the levels of ectopic Smo activity correlated with the levels of Smo phosphorylation. Hence, increasing levels of Smo phosphorylation progressively increased its signaling activity.

Fig 6. Graded Smo activity generated by phospho-mimetic mutations in PKA/CK1, Gprk2 and Gish phosphorylation sites.

(A–D") Wing discs expressing the indicated Smo constructs with C765 were immunostained to show the expression of GFP, ptc-lacZ, and En. C765>SmoSDall-CFP induced ectopic en expression in a broader domain of A-compartment cells than C765>SmoSDGPSD-CFP (indicated by the brackets in C", D"). (E) ptc-luciferase reporter assay in Cl8 cells expressing the indicated Smo constructs and treated with Hh-conditioned or control medium. Data are means ± SD of normalized ptc-luc activity from three independent experiments. P-values are Student's t tests. (F) FRET efficiency from SmoSD123-CFPC/SmoSD123-YFPC and SmoSDCL-IISA-CFPC/ SmoSDCL-IISA-YFPC expressed in S2 cells. Data are means ± SD, n = 10 cells. P-values are Student's t tests.

Our previous studies revealed that phosphorylation of Smo C-tail induced a conformational change resulting in its dimerization/oligomerization, as indicated by an increased fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) between C-terminally tagged CFP and yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) [12,24]. We found that mutating the CL-II site in SmoSD123 reduced its C-terminal FRET (Fig 6F), suggesting that CL-II phosphorylation may promote the active Smo conformation.

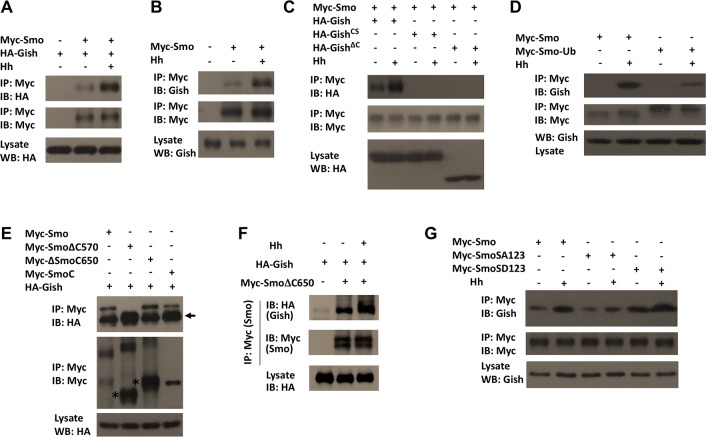

Smo and Gish Form a Complex Stimulated by Hh

We next sought to determine the mechanism by which Hh stimulates Smo phosphorylation by Gish. Because Gish is associated with the plasma membrane, we speculated that Hh might stimulate the formation of a Smo-Gish complex at cell surface. Indeed, when expressed in S2 cells, Myc-Smo coimmunoprecipitated with endogenous Gish as well as coexpressed HA-Gish, and the amount of Gish in the Smo immunoprecipitates dramatically increased after Hh stimulation (Fig 7A and 7B). The formation of the Smo-Gish complex depends on the plasma membrane association of Gish, as Myc-Smo failed to pull down the cytosolic forms of Gish, HA-GishCS, and HA-GishΔC (Fig 7C). In addition, Myc-Smo-Ub pulled down much less Gish compared with Myc-Smo after Hh stimulation (Fig 7D), suggesting Hh-induced Smo cell surface localization of Smo is critical for its interaction with Gish.

Fig 7. Gish forms a complex with Smo regulated by Hh and PKA.

(A–G) Western blots of coimmunoprecipitation experiments from lysates of S2 cells transfected with the indicated constructs. Cells were grown in the presence or absence of Hh stimulation for 24 h. In A–D and G, cells were exposed to MG132 (50 μM) for 4 h before harvest. Myc-Smo coimmunoprecipitated with HA-Gish but not HA-GishCS or HA-GishCS, and Smo/Gish association was enhanced by Hh stimulation (C). Preventing Smo cell surface accumulation by artificially conjugating an Ub moiety to the C-terminus of Smo (Myc-Smo-Ub) diminished its interaction with Gish (D). HA-Gish interacted with Myc-Smo, Myc-SmoΔ650, and Myc-SmoC but not with Myc- SmoΔ570 (E). Arrow indicates IgG and asterisks indicate monomeric forms of SmoΔ570 and SmoΔ650 (E). Hh stimulation increased the association between HA-Gish and Myc-SmoΔ650 (F). The SA mutation reduced while the SD mutation enhanced Smo/Gish association (G).

When cotransfected into S2 cells, HA-Gish formed a complex with Myc-SmoCT (Smo C-tail) but failed to bind Myc-SmoΔC570, which lacks the C-tail (Fig 7E), suggesting that Smo interacts with Gish through its C-tail. HA-Gish was also associated with Myc-SmoΔC650 in S2 cells (Fig 7E). Furthermore, this association was enhanced upon Hh stimulation (Fig 7F), suggesting that Hh signaling facilitates the binding of Gish to the membrane proximal region of the Smo C-tail.

Finally, we determined whether Smo-Gish association is regulated by PKA-mediated phosphorylation of Smo. We found that mutating the PKA phosphorylation sites to Ala (SA123) attenuated Hh-stimulated Smo-Gish complex formation, whereas the phospho-mimetic mutations of PKA sites and adjacent CK1 sites (SD123) increased both the basal and Hh-stimulated Smo-Gish complex (Fig 7G). The influence of PKA phosphorylation of Smo on Smo-Gish interaction could explain why CL-II phosphorylation is affected by PKA (Fig 4G and 4H).

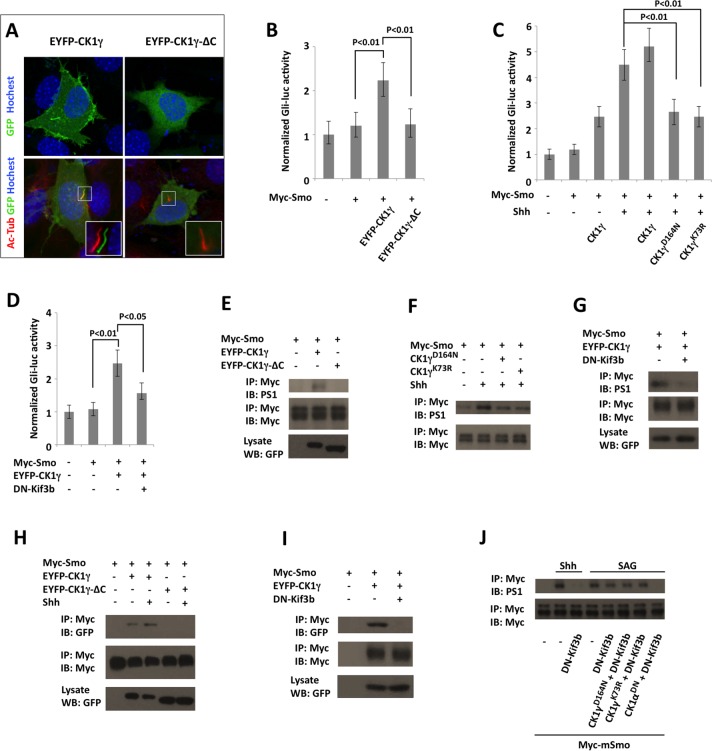

Ciliary Localized CK1γ Regulates Smo Phosphorylation and Shh Signaling

We next determine whether CK1γ regulates Shh signaling in mammalian cells. When expressed in NIH3T3 cells, an enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP)-tagged Xenopus CK1γ (EYFP-CK1γ) was accumulated on the plasma membrane as well as on the primary cilium, whereas a cytosolic form of CK1γ, EYFP-CK1γ-ΔC, which lacks the C-terminal palmitoylation site [30], failed to localize on the primary cilium (Fig 8A), suggesting that ciliary localization of CK1γ depends on its plasma-membrane association. In a Gli-luciferase (Gli-luc) reporter assay, EYFP-CK1γ but not EYFP-CK1γ-ΔC stimulated Shh pathway activity (Fig 8B). By contrast, two dominant-negative forms of CK1γ CK1γK73R and CK1γD164N, which specifically inhibited CK1γ activity [30], suppressed Shh-stimulated Gli-luc reporter activity (Fig 8C). Our previous study revealed that Shh stimulated the phosphorylation of mammalian Smo C-tail at multiple clusters of Ser/Thr residues, including a membrane-proximal cluster (S1) important for Smo activation [15]. Western blot analysis using an antibody (PS1), which recognizes phosphorylated S1 site [15], indicated that overexpression of EYFP-CK1γ but not EYFP-CK1γ-ΔC could stimulate Smo phosphorylation at the S1 site (Fig 8E). On the other hand, overexpression of either CK1γK73R or CK1γD164N attenuated Shh-stimulated S1 phosphorylation (Fig 8F). We found that EYFP-CK1γ and Myc-Smo formed a complex when coexpressed in NIH3T3 cells and that CK1γ/Smo association was enhanced upon Shh stimulation (Fig 8H). By contrast, EYFP-CK1γ-ΔC failed to interact with Smo even in the presence of Shh (Fig 8H). Because EYFP-CK1γ-ΔC failed to accumulate on the primary cilium, we speculated that the function of CK1γ in the regulation of Smo phosphorylation and Shh pathway activity might depend on the primary cilium. To disrupt the primary cilium, we overexpressed a dominant negative form of Kif3b (DN-Kif3b), a subunit of the Kinesin-II motor required for the cilium formation [15,44]. Indeed, DN-Kif3b overexpression blocked CK1γYFP/Myc-Smo association (Fig 8I), CK1γ-stimulated S1 phosphorylation (Fig 8G), and Gli-luc reporter activity (Fig 8D), suggesting that the primary cilium is required for CK1γ to bind and phosphorylate Smo.

Fig 8. Cilium-localized CK1γ promotes Smo phosphorylation and Shh pathway activity.

(A) NIH3T3 transfected with EYFP-CK1γ or EYFP-CK1γ-ΔC were immunostained with antibodies against acetylated tubulin (Ac-Tub), GFP, and Hoechst. EYFP-CK1γ but not EYFP-CK1γ-ΔC was localized on the primary cilium. (B–D) Gli-luciferase assay in NIH3T3 cells transfected Myc-Smo and the indicated CK1γ expression constructs in the presence or absence of DN-Kif3b, and treated with or without Shh. Data are means ± SD of normalized Gli-luc activity from three independent experiments. P-values are Student's t tests. (E–G) NIH3T3 cells were transfected Myc-Smo and the indicated CK1γ expression constructs in the presence or absence of DN-Kif3b, and treated with or without Shh. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with Myc antibody followed by western blot analysis with Myc and PS1 antibodies. (H, I) NIH3T3 cells were transfected with Myc-Smo and the indicated CK1γ expression constructs in the presence or absence of DN-Kif3b and treated with or without Shh. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with Myc antibody followed by western blot analysis with GFP and Myc antibodies. (J) NIH3T3 cells were transfected with the indicated constructs and treated with or without Shh or SAG, followed by immunoprecipitation and western blot analysis with the indicated antibodies.

A recent study revealed that the cell-membrane-permeable Smo agonist SAG could activate Smo without its ciliary accumulation [45]. Indeed, we found that SAG stimulated Smo phosphorylation at the S1 site in NIH3T3 cells transfected with DN-Kif3b, although Shh failed to stimulate Smo phosphorylation in these cells (Fig 8J), suggesting that SAG can induce Smo phosphorylation in the absence of the primary cilia, albeit at lower efficiency than in the presence of the primary cilia. This cilium-independent Smo phosphorylation was abolished when cells were transfected with a dominant negative form of CK1α (CK1αDN [46]); however, the dominant negative forms of CK1γ (CK1γK73R and CK1γD164N) failed to block cilium-independent Smo phosphorylation induced by SAG (Fig 8J). These results further support the notion that CK1γ regulates Smo phosphorylation in the primary cilium.

Discussion

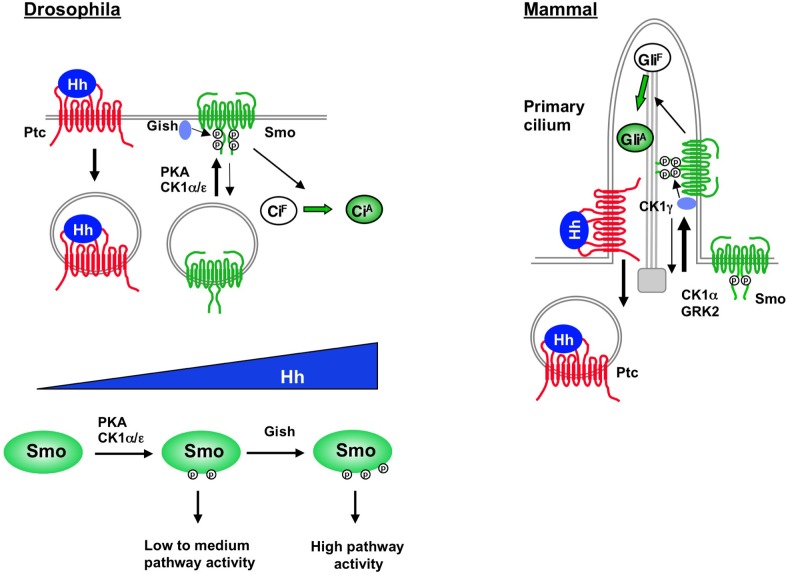

In this study, we identified a plasma membrane-associated kinase Gish/CK1γ as a conserved positive regulator of the Hh pathway. We found that Hh stimulated the binding of Gish/CK1γ to Smo to phosphorylate a Ser/Thr cluster located in the membrane-proximal region of the Smo C-tail (CL-II site in Drosophila Smo and S1 site in mammalian Smo). We demonstrated that CL-II phosphorylation is required for the optimal Smo activation and Hh pathway activity. Interestingly, we found that Gish/CK1γ regulates Smo phosphorylation and Hh pathway activity depending on its plasma membrane/ciliary localization. We propose that cell surface/ciliary accumulation of Smo, which is facilitated by Hh stimulation, promotes its association, phosphorylation, and activation by Gish/CK1γ (Fig 9).

Fig 9. Plasma membrane/cilium-localized Gish/CK1γ modulates Hh signaling by phosphorylating Smo.

Hh stimulates cell surface/ciliary accumulation of Smo, which facilitates its association, phosphorylation, and activation by Gish/CK1γ. In Drosophila, Hh morphogen gradient generates increasing levels of Smo activity by differential regulation of PKA/CK1- and Gish-mediated phosphorylation of Smo. See text for details.

As an obligatory transducer of the Hh signal, Smo relays the positional information imposed by Hh morphogen gradient to different levels of pathway activity that elicit distinct developmental outcomes. How Smo is differentially activated by Hh morphogen gradient is incompletely understood; however, it has been suggested that different levels of Hh induce different levels of Smo phosphorylation, which are in turn translated into different levels of Hh pathway activity [16]. Indeed, it has been observed that increasing levels of Hh resulted in a progressive increase in the overall levels of Smo phosphorylation, and that increasing the number of phospho-mimetic mutation in the Smo C-tail led to a gradual increase in Hh pathway activity [11,12,15,40]. A previous study revealed that, in cultured Drosophila cells exposed to Hh, Smo was phosphorylated on at least 26 Ser/Thr residues in its C-tail [20]. While the distal phosphorylation sites including the three PKA/CK1 phosphorylation clusters have been well characterized, the biological function of and the kinases involved in the phosphorylation of the membrane-proximal sites, most notably the CL-II site, have remained largely unexplored. In addition, it remains unclear whether phosphorylation of CL-II is constitutive or stimulated by Hh because its phosphorylation state was not determined in the absence of Hh stimulation.

In this study, we generated an antibody (Smo4P) that recognized phosphorylated CL-II and demonstrated that CL-II phosphorylation was stimulated by Hh. Moreover, we found that CL-II phosphorylation was mediated by Gish in a manner depending on its membrane association. Both gish mutation and phosphorylation deficient CL-II mutation affected the expression of only high-threshold Hh target genes such as en, suggesting that Gish-mediated CL-II phosphorylation is not absolutely required for Hh signal transduction but rather plays a modulatory function in fine-tuning Hh signaling strength. We noticed that the reduction of Hh pathway activity in gish mutant clones was less severe compared with that associated with CL-II mutation (Fig 2, S2 Fig and Fig 5). One possibility is that we did not completely overcome the perdurance issue even when gish clones were generated at 24–48 h AEL. The early-expressed gish gene products could persist even after many rounds of cell division, and residual Gish kinase activity might still exist in gish mutant cells to partially phosphorylate CL-II. Indeed, we didn't observe any change in Hh pathway target gene expression in gish mutant clones generated at 48–72 h AEL, many of which are >30 cells in size, suggesting that gish gene products generated at early time points survived many rounds of cell divisions. Another possibility is that in the absence of Gish or when Gish activity is compromised, another kinase(s)—for example, other members of CK1 family—may partially compensate for the loss of Gish, although these kinases do not phosphorylate CL-II as effectively as Gish.

A recent study suggested that CL-II phosphorylation was mediated by Gprk2 without providing direct evidence [38]. However, we found that CL-II phosphorylation was not affected by Gprk2 knockdown or overexpression (S3 Fig). In addition, a recombinant GRK failed to phosphorylate a Smo fragment containing the CL-II site in an in vitro kinase assay [24]. Instead, our previous study indicated that Gprk2 phosphorylated Smo at Ser/741/Thr742 (GPS1) and Ser1013/Ser1015 (GPS2) and that mutating these sites to nonphosphorable Ala in the SmoSD123 background attenuated the activity of this constitutively active form of Smo [24]. Here, we further demonstrated that Smo with Gprk2 site mutated (SmoGPSA) failed to activate en in smo mutant clones located near the A/P boundary (S6 Fig), suggesting that Gprk2-mediated Smo phosphorylation is also required for high-levels of Hh signaling activity. Interestingly, both Gish- and Gprk2-mediated phosphorylation was regulated by PKA (Fig 4) [24], which phosphorylated Smo at S667, S687, and S740 [19–21]. Indeed, mutating the three PKA sites to Ala (SmoSA123) diminished while converting the PKA sites and adjacent CK1 sites to phospho-mimetic residues (SmoSD123) promoted CL-II phosphorylation. Although SmoSD123 could activate both low- and high-threshold Hh target genes when expressed at high levels, expression of SmoSD123 at close to physiological levels resulted in low to intermediate levels of Hh pathway activity (Fig 6A–6A") [19]. Phospho-mimetic mutations at Gprk2 or both Gprk2 and Gish sites in the SmoSD123 background resulted in a progressive increase in its activity (Fig 6D-6D"). Hence, Hh-induced phosphorylation of Smo at PKA sites may confer low to medium levels of pathway activation, while high levels of pathway activity require further phosphorylation by Gish and Gprk2, which is "primed" by PKA-mediated phosphorylation. Consistent with CL-II being critical for high-threshold Hh target gene expression, its phosphorylation requires higher levels of Hh or longer exposure to the same levels of Hh than PKA site phosphorylation (Fig 4I and 4J), suggesting graded Hh signals may differentially regulate PKA- and Gish-mediated phosphorylation of Smo to progressively increase Smo activity (Fig 9).

How does PKA regulate CL-II phosphorylation? Our previous study revealed that Smo adopts a closed conformation in which its C-terminal region folds back and lies in close proximity to its third intracellular loop, whereas Hh-induced phosphorylation at PKA/CK1 sites promotes an open conformation [12]. It is possible that the Gish-binding pocket is masked when Smo C-tails adopt the closed conformation, whereas phosphorylation-mediated conformation switch exposes the Gish-binding pocket. Indeed, we found SmoSD123 exhibited high basal binding to Gish, whereas SmoSA123 lost Hh-stimulated binding to Gish (Fig 7G). However, Hh could further stimulate the binding of Gish to SmoSD123 and increase CL-II phosphorylation in SmoSD123 (Figs 4H and 7G), implying that Hh could regulate Smo/Gish association and CL-II phosphorylation through additional mechanism(s). We noticed that Hh increased the binding of Gish to SmoΔ650 (Fig 7F), which lacks the C-terminal region, including the three PKA sites, suggesting that Hh signaling may induce a conformation change in the transmembrane helixes of Smo, similar to those observed for GPCRs in response to agonist stimulation [47], to expose the juxtamembrane binding site for Gish.

Hh-induced phosphorylation of Smo by PKA promotes its cell surface accumulation [19], which may also contribute the elevated CL-II phosphorylation upon Hh stimulation. In this regard, it is interesting to note that Gish is associated with the plasma membrane through its C-terminal palmitoylation. Cell surface accumulation of Smo will render its close proximity with the plasma membrane-associated Gish and facilitate its binding to Gish. Indeed, Smo failed to bind cytosolic forms of Gish, GishCS and GishΔC, both of which were unable to phosphorylate the CL-II site in response to Hh stimulation. In addition, artificial conjugation of a ubiquitin moiety to Smo (Myc-Smo-Ub) prevented Hh-stimulated Smo cell surface accumulation, Smo-Gish association, and CL-II phosphorylation (Figs 4E, 4F and 7D).

Interestingly, we found that vertebrate CK1γ is localized to the primary cilium depending on its C-terminal palmitoylation. Deleting the palmitoylation site (CK1γ-ΔC) prevented its ciliary localization, its association with mammalian Smo (mSmo), and its ability to phosphorylate mSmo and promote Shh pathway activity. Furthermore, depleting primary cilia by expressing a dominant negative for of Kif3b (DN-Kif3b) also affected CK1γ Smo interaction and phosphorylation by CK1γ. Taken together, these results suggest that only ciliary localized but not the cytosolic CK1γ is capable of phosphorylating Smo to promote Shh pathway activation. As Shh induces mSmo ciliary accumulation, we propose that ciliary accumulation of mSmo may facilitate its binding to and phosphorylation by CK1γ, which contributes to optimal Smo activation (Fig 9). Because abnormal Smo activation contributes to many types of human cancer, the finding that CK1γ is a conserved positive regulator of Hh signaling raises an interesting possibility that interfering with the interaction between CK1γ and Smo may serve as a strategy for cancer treatment.

Materials and Methods

Drosophila Mutants and Transgenes

All flies were raised on standard yeast and molasses-based food at 25°C. Gal4 drivers used in this study are MS1096 and C765 [22,24,48]. UAS transgenes are: UAS-Smo-PKA12/SmoDN, UAS-Smo-PKA123/SmoSA123, and UAS-SmoSD123 [19]; UAS-Smo-CFP, UAS-SmoSD123-CFP, UAS-SmoSDGPSD-CFP, and UAS-Smo-GPS1A2A-Fg/SmoGPSA [24]; UAS-Myc-Gish (BL#41764), UAS-Myc-GishΔC (BL#41769), and UAS-Myc-GishKD (BL#41766); UAS-Flag-CK1α and UAS-Flag-CK1ε [31]; and UAS-GishRNAi (VDRC#106826, VDRC#26003, and BL#28066). Xenopus CK1γ DNA constructs are: pCS-EYFP-CK1γ, pCS-EYFP-CK1γ -ΔC, pCS-CK1γ D164N, and pCS-CK1γ K73R [30]. Mutant flies are: smo3 [10], gishKG03891/gishP (BL#13263), Gprk2Δ15 [24], Df(3R)ED10639 (BL#9481). gishΔ4 was generated by imprecise excision of the P-element from gishKG03891. GishCS, SmoCL-IISA (S626A, S627A, S633A, S634A), SmoCL-IISD (S626D, S627D, S633D, S634D), SmoSDCL-IISA, SmoSDCL-IISD, and SmoSDall were generated by PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis and confirmed by DNA sequencing. Mutant clones were generated by standard FRT/FLP mediated mitotic recombination or the MARCM system as previously described [36,49]. Mutant clones were generated using the following genotype: MARCM clones for gishΔ4 (yw hs-FLP; tub-Gal4; FRT82B tubGal80/FRT82B gishΔ4), gishΔ4 clones in Minute background (yw hs-FLP; FRT82B M(3) hs-CD2/FRT82B gishΔ4), gishP/P wings expressing SmoDN (yw MS1096 UAS-Flp; UAS-Smo-PKA12; FRT82B M(3) hs-CD2/FRT82B gishKG03891), smo clones with or without expressing smo transgenes (yw hs-FLP UAS-GFP; tubGal80 FRT40/smo3 FRT40; tub-Gal4, yw hs-FLP; tubGal80 FRT40/smo3 FRT40; C765/UAS-Smo-CFP or SmoCL-IISA-CFP, or yw hs-FLP UAS-GFP; tubGal80 FRT40/smo3 FRT40; C765/ UAS-Smo-GPSA).

Cell Culture, Transfection, Immunostaining, Immunoprecipitation, and Western Blot and FRET Analysis

Drosophila S2 cells were cultured in Drosophila SFM (Invitrogen) with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml of penicillin, and 100 mg/ml of streptomycin at 24°C. Transfections were carried out using the Calcium Phosphate Transfection Kit (Specialty Media). Hh-conditioned medium treatment was carried out as described [50]. Unless mentioned otherwise, Hh-conditioned medium was used at a 6:4 dilution ratio by fresh medium (referred to as 100% Hh). NIH3T3 cells were cultured in DMEM (Sigma-Aldrich) containing 10% bovine calf serum (ATCC) and were transfected using the GenJet Plus In Vitro DNA Transfection Kit (SignaGen). Immunostaining and western blot analyses were carried out using standard protocols as previously described [49,51]. For immunoprecipitation assay, S2 cells were harvested and washed twice with PBS after transfection for 48 h and then lysed on ice for 30 min with lysis buffer containing 1M Tris pH8.0, 5M NaCl, 1M NaF, 0.1M Na3VO4, 1% NP-40, 10% Glycerol, and 0.5M EDTA (pH8.0). Cell lysates were incubated with protein A–Sepharose beads (Thermo scientific) for 1 h at 4 C° to eliminate non-specific binding proteins. After removal of the protein-A beads by centrifugation, the cleared lysates were incubated with Myc (HA or Flag) antibody for 2 h or overnight. The complexes were collected by incubation with protein A–Sepharose beads for 1 h at 4 C°, followed by centrifugation. The immunoprecipitates were then washed three times for 5 min each with lysis buffer and were fractionated by SDS–PAGE. FRET analysis was carried out as previously described [12]. Antibodies used for this study are rat anti-Ci, 2A1 [52], mouse anti-Ptc (DSHB), mouse anti-En (DSHB), mouse anti-SmoN (DSHB), mouse anti-HA (Santa Cruz), rabbit anti-LacZ (Affinity Bioreagents), rabbit anti-GFP (Invitrogen), and mouse anti-Flag (Sigma). Rabbit anti-Smo4P antibody was generated by Abmart (http://www.ab-mart.com) using the synthetic phosphopeptide NDLN(PS)(PS)E(PT)NDI(PS)STW-C as antigen. The reactive antibody was purified by absorption on a phosphopeptide affinity column and was further purified by subtraction on a column containing a non-phosphopeptide DLNSSETNDISSTW-C. The resulting antibody was initially characterized by western blot analysis using GST-Smo601-700 and GST-Smo601-700CL-IISA.

In Vitro Kinase Assay, Luciferase Assay, and RNAi in Drosophila Cultured Cells

In vitro kinase assay was performed as previously described [15]. Briefly, GST-fusion proteins were mixed with 0.1 mM ATP, 10 mCi γ-32p-ATP, and CK1δ (New England Biolabs) and incubated at 30°C for 1.5 h in reaction buffer. Phosphorylation of GST-fusion proteins was analyzed by autoradiography after SDS-PAGE. For ptc-luc reporter assays, Cl8 cells were transfected with 1 μg ptc-luc reporter construct and 50 ng RL-PolII renilla construct in 12 well plates together with 1 μg Smo constructs. After 48 h incubation, the reporter assays were performed using the Dual-Luciferase reporter assay system (Promega). Dual-Luciferase measurements were performed in triplicate using FLUOstar OPTIMA (BMG LABTECH). Gli-luc reporter assays were carried out as previously described [15]. Double-stranded (ds) RNA was generated by MEGAscript High Yield Transcription Kit (Ambion). Gish dsRNA targeting the coding region (amino acids 196–474) was generated by PCR using the primers 5′-GAATTAATACGACTCACTATA GGGAG AGGCAGAAC GTCAACAAAACGT-3 and 5′-GAATTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGA GATTTTTGGCGCGTCGATTTCTT-3′. Gish dsRNA targeting the 5' UTR was generated by PCR using the primers 5'-GAATTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGAAAAGTGTGTTTGTCAAATTGT-3' and 5'-GAATTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAG ACTCACCGCCCACACTCACACG-3 '. Gprk2 dsRNA was generated by PCR using DNA template targeting Gprk2 amino acids 124–290 as described [24]. For the RNAi knockdown experiments, S2 cells were cultured in serum-free medium containing the indicated dsRNA for 8 h at 24°C. After adding FBS to a final concentration of 10%, dsRNA-treated cells were cultured for 24 h before transfection. Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were collected for analyses.

Supporting Information

(A–B') Gish expression visualized by immunostaining with a Gish antibody in a control wing disc (A, A') and a wing disc expressing UAS-Gish-RNAi by ptc-Gal4 (B, B'). dpp-lacZ expression marks the A-compartment cells near the A/P boundary. (C–J) Adult wings of the indicated genotypes. Gish RNAi enhanced the MS>SmoDN (E, F; compared with Fig 1B); however, neither Gish RNAi nor Gish overexpression modified the wing phenotype caused by Fu RNAi. (K–M) Wing discs expressing the indicated Myc-tagged Gish constructs were immunostained with a Myc antibody to show similar expression levels of Gish proteins.

(TIF)

(A–F") Wing discs carrying control or gishΔ4 clones generated by the MARCM system were immunostained for GFP (green), Gish (red in A', A", B', B"), Ptc (red in C', C", D', D"), Ci (red in E, E", F, F"), and En (blue in E', E", F', F"). Clones were induced at 48–72 h AEL and marked by GFP expression. Gish expression was abolished in gishΔ4 clones (B–B"). Neither ptc nor en expression was affected in gishΔ4 clones (arrows in D–D", F–F"). (G–H‴) A control wing disc (G, G') or wing disc carrying gishΔ4 clones generated in the Minute background at 24–48 h AEL were immunostained with Ci, Ptc, and Gish antibodies. ptc expression was not affected in gishΔ4 clones marked by the lack of Gish signal (arrows in H–H‴).

(TIF)

(A) S2 cells stably expressing Myc-Smo were treated with control or Gprk2 dsRNA and with or without Hh-conditioned medium, followed by immunoprecipitation and western blot analysis with the indicated antibodies. Western blot (middle panel) and RT-qPCR (right) experiments confirm Gprk2 knockdown efficiency.(B, C) Western blots of coimmunoprecipitation experiments from lysates of S2 cells transfected with Myc-Smo and the indicated CK1 or Gprk2 constructs. Cells were grown in the presence or absence of Hh stimulation for 24 h and exposed to MG132 (50 μM) for 4 h before harvesting.

(TIF)

(A) Western blot of coimmunoprecipitation experiments from lysates of S2 cells transfected with Myc-Smo or Myc-Smo-Ub together with mC*-YFP (a constitutively active form of PKA). Both Myc-Smo and Myc-Smo-Ub were phosphorylated by mC* at S687.(B) S2 cells were transfected with Myc-Smo or Myc-Smo-Ub either alone or together with mC*-YFP, followed by immunostaining to visualized cell surface Myc-Smo or Myc-Smo-Ub and mC*-CFP. Coexpression with the constitutively active form of PKA resulted in cell surface accumulation of both Myc-Smo and Myc-Smo-Ub.

(TIF)

(A–D') dpp-lacZ and GFP expression in wing discs expressing the indicated Smo construct in the presence or absence Flag-Gish. Coexpression of Flag-Gish with Smo-CFP promoted its activity as indicated by more robust ectopic dpp-lacZ expression and enhanced overgrowth of the wing disc (B–B' compared with A–A'). Coexpression of Flag-Gish with SmoCL-IISA-CFP did not cause discernable change in the expression of dpp-lacZ or disc growth (D–D' compared with C–C'). (E–F‴) Wing discs carrying smo3 mutant clones expressing C765>Smo-CFP (E–E‴) or C765>SmoCL-IISA-CFP (F–F‴) were treated with 50 nM LMB for 2 h prior to immunostaining with GFP, Ci, and En antibodies. Both Smo-CFP and SmoCL-IISA-CFP promote Ci nuclear localization in smo mutant clones near the A/P boundary.

(TIF)

(A–B‴) Wing discs carrying smo3 mutant clones expressing C765>SmoGPSA12 were immunostained to show the expression of GFP (green), which marks the smo mutant cells, Ci (red), and En (blue in A", A‴) or Ptc (blue in B", B‴). Expression of SmoGPS1A2A with C765 rescued ptc but not en expression in smo3 mutant clone near the A-P boundary (arrowheads). (C–D'') Wing discs expressing C765>SmoSD123-CFP (C–C") or C765>SmoSDGPSA-CFP (D–D") were immunostained to show the expression of GFP, Ptc, and En. SmoSDGPSA exhibited reduced activity compared with SmoSD123.

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Ronald Davis for providing the Gish antibody, Dr. Christof Niehrs for providing Xenopus CK1γ constructs, Bloomington and VDRC stock centers for fly strains, and DSHB for antibodies.

Abbreviations

- AEL

after egg laying

- aPKC

atypical protein kinase C

- Arr

Arrow

- CFP

Cyan fluorescent protein

- Ci

Cubitus interruptus

- CK1

casein kinase 1

- CK2

casein kinase 2

- Cl8

Clone 8

- CL-II

cluster II

- C-tail

carboxyl-terminal intracellular tail

- EYFP

enhanced yellow fluorescent protein

- En

Engrailed

- FRET

Fluorescence resonance energy transfer

- Fu

Fused

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- Gish

Gilgamesh

- Gli

Glioma-associated oncogene homologue

- GPCR

G protein coupled receptor

- Gprk2/GRK2

G protein coupled receptor kinase 2

- GST

Glutathione S-transferase

- Hh

Hedgehog

- mSmo

mammalian Smo

- PCP

planar cell polarity

- PKA

protein kinase A

- Ptc

Patched

- SAID

Smo auto-inhibitory domain

- Ser

Serine

- Shh

Sonic hedgehog

- Smo

Smoothened

- Thr

Threonine

- Ub

ubiquitin

- Wg

Wingless

- YFP

Yellow fluorescent protein

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

JJ received grants from the National Institute of General Medicine Sciences (GM061269, GM067045, GM118063) and the Welch Foundation (I-1603), and YC received grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31328017, 81322030, and 31271579). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Jiang J, Hui CC. Hedgehog signaling in development and cancer. Developmental cell. 2008;15(6):801–12. 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pasca di Magliano M, Hebrok M. Hedgehog signalling in cancer formation and maintenance. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3(12):903–11. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Briscoe J, Therond PP. The mechanisms of Hedgehog signalling and its roles in development and disease. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2013;14(7):418–31. Epub 2013/05/31. 10.1038/nrm3598 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taipale J, Beachy PA. The Hedgehog and Wnt signalling pathways in cancer. Nature. 2001;411(6835):349–54. 10.1038/35077219 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ingham PW, McMahon AP. Hedgehog signaling in animal development: paradigms and principles. Genes & development. 2001;15(23):3059–87. 10.1101/gad.938601 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petrova R, Joyner AL. Roles of Hedgehog signaling in adult organ homeostasis and repair. Development. 2014;141(18):3458–71. 10.1242/dev.083691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson CW, Chuang PT. Mechanism and evolution of cytosolic Hedgehog signal transduction. Development. 2010;137(13):2079–94. Epub 2010/06/10. 137/13/2079 [pii] 10.1242/dev.045021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robbins DJ, Fei DL, Riobo NA. The Hedgehog signal transduction network. Science signaling. 2012;5(246):re6 Epub 2012/10/18. 10.1126/scisignal.2002906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stone DM, Hynes M, Armanini M, Swanson TA, Gu Q, Johnson RL, et al. The tumour-suppressor gene patched encodes a candidate receptor for Sonic hedgehog. Nature. 1996;384(6605):129–34. 10.1038/384129a0 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen Y, Struhl G. Dual roles for patched in sequestering and transducing Hedgehog. Cell. 1996;87(3):553–63. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jia J, Tong C, Jiang J. Smoothened transduces Hedgehog signal by physically interacting with Costal2/Fused complex through its C-terminal tail. Genes & development. 2003;17(21):2709–20. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao Y, Tong C, Jiang J. Hedgehog regulates smoothened activity by inducing a conformational switch. Nature. 2007;450(7167):252–8. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rohatgi R, Milenkovic L, Scott MP. Patched1 regulates hedgehog signaling at the primary cilium. Science. 2007;317(5836):372–6. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corbit KC, Aanstad P, Singla V, Norman AR, Stainier DY, Reiter JF. Vertebrate Smoothened functions at the primary cilium. Nature. 2005;437(7061):1018–21. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Y, Sasai N, Ma G, Yue T, Jia J, Briscoe J, et al. Sonic Hedgehog dependent phosphorylation by CK1alpha and GRK2 is required for ciliary accumulation and activation of smoothened. PLoS Biol. 2011;9(6):e1001083 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Y, Jiang J. Decoding the phosphorylation code in Hedgehog signal transduction. Cell research. 2013;23(2):186–200. 10.1038/cr.2013.10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li S, Chen Y, Shi Q, Yue T, Wang B, Jiang J. Hedgehog-regulated ubiquitination controls smoothened trafficking and cell surface expression in Drosophila. PLoS Biol. 2012;10(1):e1001239 Epub 2012/01/19. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xia R, Jia H, Fan J, Liu Y, Jia J. USP8 promotes smoothened signaling by preventing its ubiquitination and changing its subcellular localization. PLoS Biol. 2012;10(1):e1001238 Epub 2012/01/19. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jia J, Tong C, Wang B, Luo L, Jiang J. Hedgehog signalling activity of Smoothened requires phosphorylation by protein kinase A and casein kinase I. Nature. 2004;432(7020):1045–50. 10.1038/nature03179 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang C, Williams EH, Guo Y, Lum L, Beachy PA. Extensive phosphorylation of Smoothened in Hedgehog pathway activation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101(52):17900–7. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Apionishev S, Katanayeva NM, Marks SA, Kalderon D, Tomlinson A. Drosophila Smoothened phosphorylation sites essential for Hedgehog signal transduction. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7(1):86–92. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li S, Ma G, Wang B, Jiang J. Hedgehog induces formation of PKA-Smoothened complexes to promote Smoothened phosphorylation and pathway activation. Science signaling. 2014;7(332):ra62 10.1126/scisignal.2005414 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng S, Maier D, Neubueser D, Hipfner DR. Regulation of smoothened by Drosophila G-protein-coupled receptor kinases. Developmental biology. 2010;337(1):99–109. Epub 2009/10/24. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.10.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen Y, Li S, Tong C, Zhao Y, Wang B, Liu Y, et al. G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 promotes high-level Hedgehog signaling by regulating the active state of Smo through kinase-dependent and kinase-independent mechanisms in Drosophila. Genes & development. 2010;24(18):2054–67. Epub 2010/09/17. 24/18/2054 [pii] 10.1101/gad.1948710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jia H, Liu Y, Xia R, Tong C, Yue T, Jiang J, et al. Casein kinase 2 promotes Hedgehog signaling by regulating both smoothened and Cubitus interruptus. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010;285(48):37218–26. Epub 2010/09/30. 10.1074/jbc.M110.174565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang K, Liu Y, Fan J, Epperly G, Gao T, Jiang J, et al. Hedgehog-regulated atypical PKC promotes phosphorylation and activation of Smoothened and Cubitus interruptus in Drosophila. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014. 10.1073/pnas.1417147111 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhu AJ, Zheng L, Suyama K, Scott MP. Altered localization of Drosophila Smoothened protein activates Hedgehog signal transduction. Genes & development. 2003;17(10):1240–52. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hummel T, Attix S, Gunning D, Zipursky SL. Temporal control of glial cell migration in the Drosophila eye requires gilgamesh, hedgehog, and eye specification genes. Neuron. 2002;33(2):193–203. Epub 2002/01/24. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knippschild U, Gocht A, Wolff S, Huber N, Lohler J, Stoter M. The casein kinase 1 family: participation in multiple cellular processes in eukaryotes. Cell Signal. 2005;17(6):675–89. Epub 2005/02/22. S0898-6568(04)00297-9 [pii] 10.1016/j.cellsig.2004.12.011 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davidson G, Wu W, Shen J, Bilic J, Fenger U, Stannek P, et al. Casein kinase 1 gamma couples Wnt receptor activation to cytoplasmic signal transduction. Nature. 2005;438(7069):867–72. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang L, Jia J, Wang B, Amanai K, Wharton KA Jr., Jiang J. Regulation of wingless signaling by the CKI family in Drosophila limb development. Developmental biology. 2006;299(1):221–37. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tan Y, Yu D, Pletting J, Davis RL. Gilgamesh is required for rutabaga-independent olfactory learning in Drosophila. Neuron. 2010;67(5):810–20. Epub 2010/09/10. 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.08.020 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gault WJ, Olguin P, Weber U, Mlodzik M. Drosophila CK1-gamma, gilgamesh, controls PCP-mediated morphogenesis through regulation of vesicle trafficking. The Journal of cell biology. 2012;196(5):605–21. Epub 2012/03/07. 10.1083/jcb.201107137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shi Q, Li S, Jia J, Jiang J. The Hedgehog-induced Smoothened conformational switch assembles a signaling complex that activates Fused by promoting its dimerization and phosphorylation. Development. 2011;138(19):4219–31. Epub 2011/08/20. dev.067959 [pii] 10.1242/dev.067959 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ruel L, Rodriguez R, Gallet A, Lavenant-Staccini L, Therond PP. Stability and association of Smoothened, Costal2 and Fused with Cubitus interruptus are regulated by Hedgehog. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5(10):907–13. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee T, Luo L. Mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker (MARCM) for Drosophila neural development. Trends Neurosci. 2001;24(5):251–4. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morata G, Ripoll P. Minutes: mutants of drosophila autonomously affecting cell division rate. Developmental biology. 1975;42(2):211–21. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maier D, Cheng S, Faubert D, Hipfner DR. A broadly conserved g-protein-coupled receptor kinase phosphorylation mechanism controls Drosophila smoothened activity. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(7):e1004399 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang X, Mao F, Lv X, Zhang Z, Fu L, Lu Y, et al. Drosophila Vps36 regulates Smo trafficking in Hedgehog signaling. Journal of cell science. 2013;126(Pt 18):4230–8. Epub 2013/07/12. 10.1242/jcs.128603 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fan J, Liu Y, Jia J. Hh-induced Smoothened conformational switch is mediated by differential phosphorylation at its C-terminal tail in a dose- and position-dependent manner. Developmental biology. 2012;366(2):172–84. Epub 2012/04/28. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.04.007 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ohlmeyer JT, Kalderon D. Hedgehog stimulates maturation of Cubitus interruptus into a labile transcriptional activator. Nature. 1998;396(6713):749–53. 10.1038/25533 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang G, Amanai K, Wang B, Jiang J. Interactions with Costal2 and suppressor of fused regulate nuclear translocation and activity of cubitus interruptus. Genes & development. 2000;14(22):2893–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang QT, Holmgren RA. Nuclear import of cubitus interruptus is regulated by hedgehog via a mechanism distinct from Ci stabilization and Ci activation. Development. 2000;127(14):3131–9. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen MH, Wilson CW, Li YJ, Law KK, Lu CS, Gacayan R, et al. Cilium-independent regulation of Gli protein function by Sufu in Hedgehog signaling is evolutionarily conserved. Genes & development. 2009;23(16):1910–28. Epub 2009/08/18. 23/16/1910 [pii] 10.1101/gad.1794109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fan CW, Chen B, Franco I, Lu J, Shi H, Wei S, et al. The Hedgehog pathway effector smoothened exhibits signaling competency in the absence of ciliary accumulation. Chemistry & biology. 2014;21(12):1680–9. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2014.10.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peters JM, McKay RM, McKay JP, Graff JM. Casein kinase I transduces Wnt signals. Nature. 1999;401(6751):345–50. 10.1038/43830 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rosenbaum DM, Rasmussen SG, Kobilka BK. The structure and function of G-protein-coupled receptors. Nature. 2009;459(7245):356–63. 10.1038/nature08144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang GL, Wang B, Jiang J. Protein kinase A antagonizes Hedgehog signaling by regulating both the activator and repressor forms of Cubitus interruptus. Genes & development. 1999;13(21):2828–37. 10.1101/Gad.13.21.2828 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jiang J, Struhl G. Protein kinase A and hedgehog signaling in Drosophila limb development. Cell. 1995;80(4):563–72. 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90510-3 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lum L, Yao S, Mozer B, Rovescalli A, Von Kessler D, Nirenberg M, et al. Identification of Hedgehog pathway components by RNAi in Drosophila cultured cells. Science. 2003;299(5615):2039–45. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang W, Zhao Y, Tong C, Wang G, Wang B, Jia J, et al. Hedgehog-regulated costal2-kinase complexes control phosphorylation and proteolytic processing of cubitus interruptus. Developmental cell. 2005;8(2):267–78. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Motzny CK, Holmgren R. The Drosophila cubitus interruptus protein and its role in the wingless and hedgehog signal transduction pathways. Mech Dev. 1995;52(1):137–50. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(A–B') Gish expression visualized by immunostaining with a Gish antibody in a control wing disc (A, A') and a wing disc expressing UAS-Gish-RNAi by ptc-Gal4 (B, B'). dpp-lacZ expression marks the A-compartment cells near the A/P boundary. (C–J) Adult wings of the indicated genotypes. Gish RNAi enhanced the MS>SmoDN (E, F; compared with Fig 1B); however, neither Gish RNAi nor Gish overexpression modified the wing phenotype caused by Fu RNAi. (K–M) Wing discs expressing the indicated Myc-tagged Gish constructs were immunostained with a Myc antibody to show similar expression levels of Gish proteins.

(TIF)

(A–F") Wing discs carrying control or gishΔ4 clones generated by the MARCM system were immunostained for GFP (green), Gish (red in A', A", B', B"), Ptc (red in C', C", D', D"), Ci (red in E, E", F, F"), and En (blue in E', E", F', F"). Clones were induced at 48–72 h AEL and marked by GFP expression. Gish expression was abolished in gishΔ4 clones (B–B"). Neither ptc nor en expression was affected in gishΔ4 clones (arrows in D–D", F–F"). (G–H‴) A control wing disc (G, G') or wing disc carrying gishΔ4 clones generated in the Minute background at 24–48 h AEL were immunostained with Ci, Ptc, and Gish antibodies. ptc expression was not affected in gishΔ4 clones marked by the lack of Gish signal (arrows in H–H‴).

(TIF)

(A) S2 cells stably expressing Myc-Smo were treated with control or Gprk2 dsRNA and with or without Hh-conditioned medium, followed by immunoprecipitation and western blot analysis with the indicated antibodies. Western blot (middle panel) and RT-qPCR (right) experiments confirm Gprk2 knockdown efficiency.(B, C) Western blots of coimmunoprecipitation experiments from lysates of S2 cells transfected with Myc-Smo and the indicated CK1 or Gprk2 constructs. Cells were grown in the presence or absence of Hh stimulation for 24 h and exposed to MG132 (50 μM) for 4 h before harvesting.

(TIF)

(A) Western blot of coimmunoprecipitation experiments from lysates of S2 cells transfected with Myc-Smo or Myc-Smo-Ub together with mC*-YFP (a constitutively active form of PKA). Both Myc-Smo and Myc-Smo-Ub were phosphorylated by mC* at S687.(B) S2 cells were transfected with Myc-Smo or Myc-Smo-Ub either alone or together with mC*-YFP, followed by immunostaining to visualized cell surface Myc-Smo or Myc-Smo-Ub and mC*-CFP. Coexpression with the constitutively active form of PKA resulted in cell surface accumulation of both Myc-Smo and Myc-Smo-Ub.

(TIF)