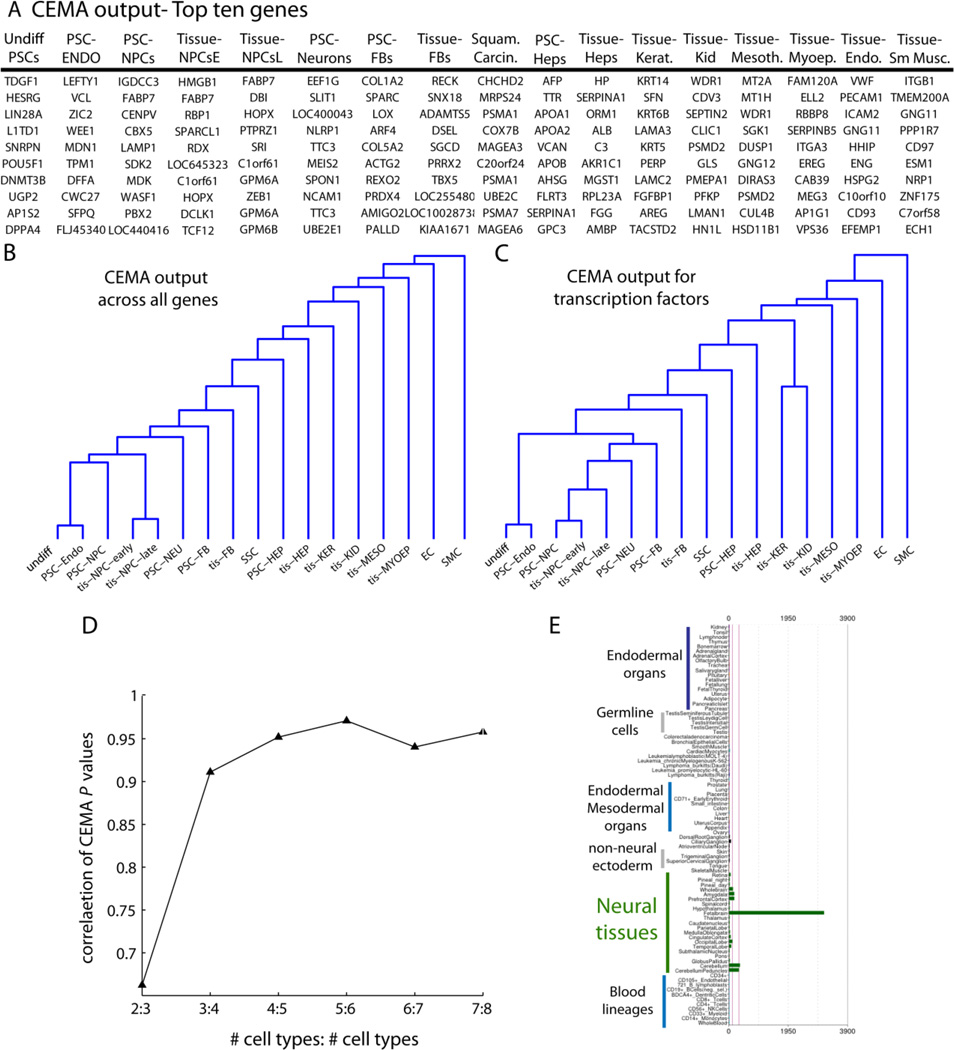

Figure 1. Analysis of 17 cell states produces unique expression modules.

(A) a table of the top 10 genes from each cell state shown. (B) and (C) Dendrograms showing the relationship between all tissues in the global analysis, using the correlation between their p-values for all genes (B) or just transcription factors (C). Note that, in general, the CEMA patterns for similar cell states appeared to be more similar for expected cell states. In other words, the list of genes ranked by their specificity for a particular cell state reflected the similarity that would be uncovered by a Pearson-type correlation. (D) Example of how the p-values stabilized as we added more and more cell types In particular, each entry on the x-axis shows the correlation between tis-HEP p-values, when X tissues, or X+1 tissues were used. For example, the 2:3 entry shows that when only two tissues were used, as compared to three tissues, that the p-values have a correlation of around 0.75. However, when we compared the p-values when 8 tissues were used, as compared to 7 (7:8) we see the correlation approaches 1. Here, the order of tissues added for comparison with tis-HEP were: tis-FB then tis-HEP, tis-KER, tis-MYOEP, tis-KID, tis-MESO, tis-NPCe, tis-NPC. (E) To assess the specificity of CEMA-identified genes, an example gene for NPCs was probed across the BioGPS database of profiled cell types from across dozens of cell types. FABP7, identified by CEMA as specific to tis-NPCs, only showed up in fetal brain samples in the Novartis dataset. Note that just a subset of cell types are labelled in the image (blue text), while the analysis was performed on all cell types. A broader analysis is available in Figure S1.