Abstract

Key points

Cerebral blood flow increases during hypercapnia and decreases during hypocapnia; it is unknown if vasomotion of the internal carotid artery is implicated in these responses.

Indomethacin, a non‐selective cyclooxygenase inhibitor (used to inhibit prostaglandin synthesis), has a unique ability to blunt cerebrovascular carbon dioxide reactivity, while other cyclooxygenase inhibitors have no effect.

We show significant dilatation and constriction of the internal carotid artery during hypercapnia and hypocapnia, respectively.

Indomethacin, but not ketorolac or naproxen, reduced the dilatatory response of the internal carotid artery to hypercapnia

The differential effect of indomethacin compared to ketorolac and naproxen suggests that indomethacin inhibits vasomotion of the internal carotid artery independent of prostaglandin synthesis inhibition.

Abstract

Extra‐cranial cerebral blood vessels are implicated in the regulation of cerebral blood flow during changes in arterial CO2; however, the mechanisms governing CO2‐mediated vasomotion of these vessels in humans remain unclear. We determined if cyclooxygenase inhibition with indomethacin (INDO) reduces the vasomotor response of the internal carotid artery (ICA) to changes in end‐tidal CO2 (). Using a randomized single‐blinded placebo‐controlled study, participants (n = 10) were tested on two occasions, before and 90 min following oral INDO (1.2 mg kg–1) or placebo. Concurrent measurements of beat‐by‐beat velocity, diameter and blood flow of the ICA were made at rest and during steady‐state stages (4 min) of iso‐oxic hypercapnia (+3, +6, +9 mmHg ) and hypocapnia (−3, −6, −9 mmHg ). To examine if INDO affects ICA vasomotion independent of cyclooxygenase inhibition, two participant subsets (each n = 5) were tested before and following oral ketorolac (post 45 min, 0.25 mg kg–1) or naproxen (post 90 min, 4.2 mg kg–1). During pre‐drug testing in the INDO trial, the ICA dilatated during hypercapnia at +6 mmHg (4.72 ± 0.45 vs. 4.95 ± 0.51 mm; P < 0.001) and +9 mmHg (4.72 ± 0.45 mm vs. 5.12 ± 0.47 mm; P < 0.001), and constricted during hypocapnia at −6 mmHg (4.95 ± 0.33 vs. 4.88 ± 0.27 mm; P < 0.05) and −9 mmHg (4.95 ± 0.33 vs. 4.82 ± 0.27 mm; P < 0.001). Following INDO, vasomotor responsiveness of the ICA to hypercapnia was reduced by 67 ± 28% (0.045 ± 0.015 vs. 0.015 ± 0.012 mm mmHg −1). There was no effect of the drug in the ketorolac and naproxen trials. We conclude that: (1) INDO markedly reduces the vasomotor response of the ICA to changes in ; and (2) INDO may be reducing CO2‐mediated vasomotion via a mechanism(s) independent of cyclooxygenase inhibition.

Key points

Cerebral blood flow increases during hypercapnia and decreases during hypocapnia; it is unknown if vasomotion of the internal carotid artery is implicated in these responses.

Indomethacin, a non‐selective cyclooxygenase inhibitor (used to inhibit prostaglandin synthesis), has a unique ability to blunt cerebrovascular carbon dioxide reactivity, while other cyclooxygenase inhibitors have no effect.

We show significant dilatation and constriction of the internal carotid artery during hypercapnia and hypocapnia, respectively.

Indomethacin, but not ketorolac or naproxen, reduced the dilatatory response of the internal carotid artery to hypercapnia

The differential effect of indomethacin compared to ketorolac and naproxen suggests that indomethacin inhibits vasomotion of the internal carotid artery independent of prostaglandin synthesis inhibition.

Abbreviations

- CBF

cerebral blood flow

- COX

cyclooxygenase

- HR

heart rate

- INDO

indomethacin

- ICA

internal carotid artery

- QICA

internal carotid artery blood flow

- ICAv

internal carotid artery blood velocity

- MAP

mean arterial pressure

- MCA

middle cerebral artery

- MCAv

middle cerebral artery blood velocity

partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide

partial pressure of end‐tidal carbon dioxide

partial pressure of end‐tidal oxygen

- PG

prostaglandin

- TCD

transcranial Doppler ultrasound

Introduction

The cerebral vasculature is highly sensitive to alterations in the partial pressure of arterial CO2 (). Elevations in (hypercapnia) cause a reduction in cerebrovascular resistance and a consequent increase in cerebral blood flow (CBF), while reductions in (hypocapnia) cause an increase in cerebrovascular resistance and a decrease in CBF (Kety & Schmidt, 1948) – the magnitude of this response is characterized as cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity. Optimal cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity acts to attenuate fluctuations in central pH and maintain homeostatic function (Ainslie & Duffin, 2009). Typically it is thought that alterations in exclusively induce vasomotion (changes in blood vessel diameter) of small pial vessels, with no vasomotion occurring within the larger cerebral arteries (Wolff & Lennox, 1930; Serrador et al. 2000). This assumption has persisted despite human (Giller et al. 1993) and animal studies (Heistad et al. 1978) providing evidence to the contrary. Recent insight from high‐resolution magnetic resonance imaging has further revealed that vasomotion of the middle cerebral artery (MCA) occurs in response to both hyper‐ and hypocapnia (Verbree et al. 2014; Coverdale et al. 2014). Additionally, using vascular ultrasound combined with automated edge detection analysis software, a tendency for vasomotion of large extra‐cranial cerebral arteries across a wide range of [e.g. internal carotid artery (ICA)] has been reported (Willie et al. 2012); however, these latter findings have not been consistently demonstrated when caliper‐based manual diameter analysis methods are used (Sato et al. 2012; Coverdale et al. 2015).

The potential mechanism(s) whereby changes in result in vasomotion of large extra‐cranial cerebral arteries include adenosine (Phillis & DeLong, 1987), nitric oxide (Parfenova et al. 1994; Smith et al. 1997) and prostaglandins (PGs; Wennmalm et al. 1981; Bruhn et al. 2001; St Lawrence et al. 2002). The last‐named mechanism has been ostensibly demonstrated in that administration of indomethacin (INDO), a non‐selective cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitor, reduces basal CBF by ∼20–30% and cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity by ∼50–60% (Eriksson et al. 1983; Xie et al. 2005; Fan et al. 2010; Hoiland et al. 2015). As illustrated in Fig. 1, this PG‐mediated vasodilatation occurs through up‐regulation of cAMP and subsequent phosphorylation (i.e. deactivation) of myosin light chain kinase (Adelstein & Conti, 1978). While animal studies report PG‐mediated hypercapnic vasodilatation at the level of the small pial vessels and arterioles (Pickard et al. 1980; Busija & Heistad, 1983; Leffler et al. 1991), some data collected in post‐mortem humans indicate that PG‐mediated vasomotion may also take place within the larger intra‐cranial cerebral arteries (i.e. MCA; Davis et al. 2004). As optimal cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity is important in stabilizing central pH, and predictive of health outcome (Portegies et al. 2014), it is imperative to understand the underlying mechanisms that regulate this response. Although COX inhibition, via INDO, reduces CBF and blunts cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity (Xie et al. 2006; Fan et al. 2010; Hoiland et al. 2015), it is unknown if this is due in part to a reduction in vasomotion of the larger extra‐cranial cerebral arteries (e.g. ICA). Lastly, in vivo (Eriksson et al. 1983; Markus et al. 1994) and in vitro (Kantor & Hampton, 1978; Goueli & Ahmed, 1980) evidence indicates that INDO exerts its vasomotor actions independent of COX inhibition. In humans, administration of COX inhibitors other than INDO (e.g. aspirin and naproxen) do not affect cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity (Eriksson et al. 1983; Markus et al. 1994). Using in vitro preparations, INDO directly inhibits cAMP (a primary regulator of vascular tone) activity (Kantor & Hampton, 1978; Goueli & Ahmed, 1980).

Figure 1. Putative affects of INDO on cerebral smooth muscle cell function .

Vasodilator prostaglandins (prostaglandin I2 and E2; PGI2 and PGE2) produced downstream of arachidonic acid bind prostaglandin receptors, which activate (→) cAMP, leading to up‐regulation of cAMP‐dependent protein kinase and subsequent inhibition (→|) of myosin light chain kinase (Adelstein & Conti, 1978). By inhibiting this response, downstream phosphorylation of myosin light chain and its consequent contribution to contraction does not occur, resulting in smooth muscle cell relaxation, and/or vasodilatation (Kerrick & Hoar, 1981). INDO probably exerts its affect(s), in addition to COX inhibition, on post‐receptor‐mediated increases in cAMP (Parfenova et al. 1995) and/or by inhibiting cAMP‐dependent protein kinase activity (Kantor & Hampton, 1978; Goueli & Ahmed, 1980).

Therefore, using a single blinded placebo‐controlled and randomized design, the purposes of this study were to: (1) resolve the conflicting data surrounding hypercapnic dilatation and hypocapnic vasoconstriction of the ICA, and (2) determine if PGs are implicated in CO2‐mediated large cerebral artery vasomotion. We hypothesized that: (1) the ICA would dilatate in response to hypercapnia and constrict in response to hypocapnia, and (2) COX inhibition with INDO would markedly attenuate the dilatatory response to hypercapnia and the constrictive response to hypocapnia in the ICA. Since INDO has demonstrated a unique ability to inhibit CO2‐mediated cerebrovascular responses when compared to other COX inhibitors (Eriksson et al. 1983; Markus et al. 1994), in follow‐up experiments, we sought to assess the effects of ketorolac and naproxen – both potent non‐selective COX inhibitors – on CO2‐mediated vasomotion of the ICA to determine if there is a unique influence of INDO under the conditions of our experimental approach. In this respect, we reasoned that neither ketorolac nor naproxen would affect the vasomotor response of the ICA to hypercapnia and hypocapnia.

Methods

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the University of British Columbia Clinical Research Ethics Board and conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki. Prior to participation in the study all participants completed written informed consent.

Participants

Fifteen healthy young volunteers were recruited to participate in this study. The main study, (INDO investigations) included ten participants (one female) with a mean age of 23 ± 7 years, and body mass index of 22 ± 2 kg m–2. The female participant was tested on days 1 and 3 of her self‐reported follicular phase, thus minimizing any potential sex difference in the response to COX inhibition and CO2 perturbations (Peltonen et al. 2015). In the follow‐up experiments, two subgroups of five participants (all male) were examined for the ketorolac (30 ± 7 years; body mass index of 24 ± 2 kg m–2) and naproxen (24 ± 3 years; body mass index of 22 ± 1 kg m–2) trials. During familiarization, participants were screened to ensure that reliable ICA ultrasound images and MCA signals could be attained. Participants were familiarized with the remaining experimental equipment and procedures during this session. All participants were free of cardiovascular, respiratory, cerebrovascular, gastro‐intestinal and liver disease, were non‐diabetic, and were not taking any prescription drugs (other than oral contraceptives; n = 1) at their time of participation, as determined by a screening questionnaire.

Experimental measures

Cardiorespiratory measures

All cardiorespiratory variables were sampled continuously throughout the protocol at 1000 Hz via an analog‐to‐digital converter (Powerlab, 16/30; ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO, USA). Heart rate (HR) was measured by a three‐lead electrocardiogram (ECG; ADI bioamp ML132), and beat‐to‐beat blood pressure by finger photoplethysmography (Finometer PRO, Finapres Medical Systems, Amsterdam, Netherlands). The Finometer reconstructed brachial waveform was used for the calculation of mean arterial pressure (MAP) after values were back calibrated to the average of three automated brachial blood pressure measurements made over 5 min (Tango+; SunTech, Morrisville, NC, USA). The partial pressure of both end‐tidal CO2 () and end‐tidal O2 () were sampled at the mouth and recorded by a calibrated gas analyser (model ML206, ADInstruments), while respiratory flow was measured by a pneumotachograph (model HR 800L, HansRudolph, Shawnee, KS, USA) connected to a bacteriological filter. All data were interfaced with LabChart (Version 7), and analysed offline. Average values for the last minute of each stage were recorded (see Experimental protocol).

Dynamic end‐tidal forcing

and were controlled by a portable dynamic end‐tidal forcing system. This system uses independent gas solenoid valves for O2, CO2 and N2 and controls the volume of each gas delivered into the inspiratory reservoir through a mixing and humidification chamber. , , both inspiratory and expiratory tidal volume, breathing frequency and minute ventilation were determined for each breath in real time using custom software (Labview 13.0, National Instruments, Austin, TX, USA). Using feedback information regarding , , and inspiratory and expiratory tidal volume, the dynamic end‐tidal forcing system adjusts the inspirate on a breath‐by‐breath basis to control end‐tidal gases at a desired target value. Feed‐forward control of the inspirate is based on estimates of baseline metabolic O2 consumption and CO2 production and employs the alveolar gas equation to determine the required volumes of O2 and CO2. Feedback control is accomplished using a proportional and integral error reduction control system. End‐tidal steady‐state for each stage (see Experimental protocol) was determined once values were within 1 mmHg of the desired target point for at least three consecutive breaths. Our end‐tidal forcing system effectively controls end‐tidal gases through wide ranges of and independent of ventilation at low altitude (Querido et al. 2013; Tymko et al. 2015, 2016), high altitude (Tymko et al. 2016), with hyperthermic interventions (Bain et al. 2013) and during exercise (our unpublished observations).

Cerebrovascular measures

Blood velocity through the right MCA (MCAv) was measured using a 2 MHz transcranial Doppler ultrasound (TCD; Spencer Technologies, Seattle, WA, USA). The TCD probe was attached to a specialized headpiece (model M600 bilateral head frame, Spencer Technologies), and then secured in place. The MCA was insonated through the middle trans‐temporal window, using previously described location and standardization techniques (Willie et al. 2011).

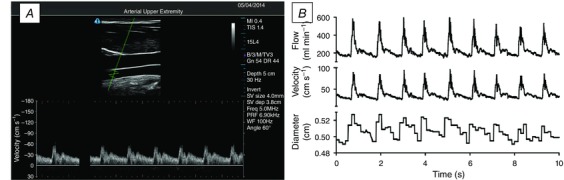

Blood velocity and vessel diameter of the ICA were measured using a 10 MHz multi‐frequency linear array vascular ultrasound (Terason T3200, Teratech, Burlington, MA, USA). Specifically, B‐mode imaging was used to measure arterial diameter, while pulse‐wave mode was used to simultaneously measure peak blood velocity (Fig. 2 A). Measures of ICA flow (Q ICA) were made ipsilateral to the MCA. The ICA diameter and velocity were measured at least 1.5 cm distal to the common carotid bifurcation to eliminate recordings of turbulent and retrograde flow. Great care was taken to ensure that the insonation angle (60 deg) was unchanged throughout each test. Furthermore, for all experimental sessions, upon acquisition of the first ultrasound image there was no alteration of B‐mode gain to avoid any artificial changes in arterial wall brightness/thickness.

Figure 2. Duplex ultrasound image of the ICA and analysis output .

A, a typical image during the recording of ICA flow, diameter and velocity. The velocity sample gate (cross‐hairs in the B‐mode image) are >1.5 cm distal to the carotid bulb, which would appear just to the right of the visible section if the image were extended. The resultant velocity waveform is free of any retrograde flow and aliasing. B‐mode depth is set to 5 cm for this recording. B, data output from a typical ICA trace, showing beat‐by‐beat flow, diameter and velocity at 30 Hz.

All of the ICA recordings were screen captured and stored as video files for offline analysis. This analysis involved concurrent determination of arterial diameter and peak blood velocity at 30 Hz, using customized edge detection and wall tracking software designed to mitigate observer bias (Fig. 2 B) (Woodman et al. 2001). Based on n = 12 young healthy subjects, unpublished findings from our laboratory show that the variability in analysis is much greater (approximately 25–30%) when using manual compared to automated approaches. Moreover, the intra‐observer variability is similarly high when using manual compared to automated approaches. No fewer than 12 consecutive cardiac cycles were used to determine Q ICA. Volumetric blood flow was calculated using the following formula:

Our within‐ and between‐day coefficients of variation for the assessment of ICA diameter are 1.5 and 4.4%, respectively. Volumetric blood flow (i.e. ICA) and velocity (i.e. MCA) values were calculated within the final minute of each 4 min steady state stage. To help account for MAP in our analysis of the CBF responses, cerebrovascular conductance (CVC) was subsequently calculated as Q ICA/MAP. As cerebrovascular reactivity to hypercapnia is approximately double that of hypocapnic reactivity, cerebrovascular responses were calculated separately for the hypercapnic and hypocapnic reactivity tests (Willie et al. 2012). All response slopes (e.g. mm mmHg −1) were calculated using linear regression (Willie et al. 2012; Skow et al. 2013; Tymko et al. 2016). The Pearson r correlation for all the diameter responses was ≥0.85, indicating linearity of the diameter responses.

Experimental protocol

On the day of experimental sessions participants arrived in the laboratory at the same time of day having refrained from alcohol, exercise and caffeine for the previous 24 h. Participants were instructed to lie supine for at least 15 min prior to beginning the study protocol and were simultaneously instrumented with the experimental equipment.

Study 1

To investigate the role of non‐selective COX inhibition via oral INDO we used a single blinded, randomized and counterbalanced placebo‐controlled trial requiring two laboratory visits. On each day, following 5 min of baseline measurements (HR, MAP, MCAv, Q ICA, and ) while breathing room air, the participants performed two iso‐oxic CO2 reactivity tests (a hypercapnic test followed by a hypocapnic test). The tests were separated by ≥10 min and a return of MAP, HR and MCAv to baseline values was confirmed prior to proceeding with the hypocapnic test. Thereafter, they were orally administered 1.2 mg kg–1 of INDO or placebo (sugar pill matched for weight and capsule size), and repeated the baseline measures and the iso‐oxic CO2 tests 90 min later (Xie et al. 2006). This dose of INDO used has been previously shown to effectively inhibit COX activity (Eriksson et al. 1983). Test days were separated by 10 ± 9 days. The iso‐oxic CO2 reactivity tests are as follows:

Test 1: Steady state iso‐oxic elevations of . Four minutes of room air breathing were completed to determine baseline and values. Following room air breathing, dynamic end‐tidal forcing was utilized to maintain and at baseline (resting) values on an individual basis for 4 min (Tymko et al. 2015, 2016). Upon completion of this baseline stage, remained unchanged while was sequentially elevated to +3, +6 and +9 mmHg above baseline, with each stage lasting 4 min after reaching steady‐state . Upon completion of the iso‐oxic CO2 reactivity protocols, participants were removed from the breathing apparatus, and recovered breathing room air.

Test 2: Steady state iso‐oxic reductions in . Four minutes of room air breathing was completed to determine baseline and values. Following room air breathing, dynamic end‐tidal forcing was utilized to maintain and at baseline (resting) values on an individual basis for 4 min (Tymko et al. 2015, 2016). Immediately after baseline, participants were instructed to actively hyperventilate to sequentially lower their to −3, −6 and −9 mmHg below baseline values while remained unchanged, with each step lasting 4 min (after had stabilized). Once participants had reached an adequate level of hyperventilation to achieve the desired , participants were instructed to maintain constant ventilation for the remainder of the stages (i.e. for −3, −6 and −9 mmHg stages). Inspiratory was then altered to achieve the desired changes required for each stage.

Study 2

To investigate the role of non‐selective COX inhibition using orally administered ketorolac (Toradol®), participants attended the lab on one occasion. Following 5 min of baseline measurements (HR, MAP, MCAv, Q ICA, and ) while breathing room air, the participants performed the identical two CO2 reactivity tests as in Study 1 (a hypercapnic test followed by a hypocapnic test). These tests were repeated 45 min later following orally administered ketorolac (0.25 mg kg–1). Previous studies have confirmed the effectiveness of COX inhibition by this dose of ketorolac at 45 min (peak plasma concentration) with an associated half‐life of ∼5–6 h (Jung et al. 1989; Jallad et al. 1990).

Study 3

To investigate the role of non‐selective COX inhibition via orally administered naproxen (Aleve®), participants attended the lab on one occasion. Following 5 min of baseline measurements (HR, MAP, MCAv, Q ICA, and ) while breathing room air, the participants performed the identical two CO2 reactivity tests as in Study 1 (a hypercapnic test followed by a hypocapnic test). These tests were repeated 90 min later following orally administered naproxen (4.2 mg kg–1). Previous studies have confirmed the effectiveness of COX inhibition by this dose of naproxen (Eriksson et al. 1983).

Statistical analysis

All cardiovascular, cerebrovascular and respiratory variables were analysed within trial (i.e. INDO, placebo, ketorolac and naproxen) using two‐way repeated measures ANOVAs. When significant F‐ratios were detected, post‐hoc comparisons were made using Tukey's honest significant difference (HSD) test. To further assess the effect of our interventions on cerebral reactivity (i.e. flow and vasomotor reactivity) specific to study 1, one‐way repeated measures ANOVAs were used to compare pre‐INDO vs. post‐INDO vs. pre‐placebo vs. post‐placebo reactivity slopes. Post‐hoc comparisons were made using Tukey's HSD test. Normality of the data was confirmed using the Shapiro–Wilks test. Reactivity slopes (i.e. mm mmHg −1) were calculated using linear regression. The effects of ketorolac and naproxen on reactivity slopes were assessed using two‐tailed paired t‐tests (pre‐ vs. post‐drug). Pearson r correlations were used to assess the relationship between MAP and vasomotor reactivity. All data are expressed as means ± standard deviation with a priori statistical significance set at P < 0.05.

Results

Study 1: INDO and placebo trials

Resting CBF and cardiorespiratory variables

Resting Q ICA was reduced by 40 ± 12% following INDO (257.3 ± 57.2 vs. 151.9 ± 36.6 ml min−1; P < 0.01), while placebo treatment had no effect (257.8 ± 62.4 vs. 252.3 ± 62.4 ml min−1; P = 0.55). Similarly, INDO reduced resting MCAv by 36 ± 11% (65.5 ± 8.6 vs. 42.0 ± 8.8 cm s−1; P < 0.01), while placebo had no effect (62.4 ± 12.4 vs. 60.7 ± 14.3 cm s−1; P = 0.43). Pre‐INDO, resting Q ICA and MCAv were not different from the pre‐placebo and placebo trials. Resting ventilation was unaffected by INDO; however, compared to the placebo, INDO caused a modest increase in MAP (77.0 ± 5.6 vs. 83.8 ± 8.7 mmHg; P = 0.03) and decreased HR (57.4 ± 11.0 vs. 49.9 ± 8.6 beats min−1; P < 0.01).

INDO CO2 trials

Cardiovascular, cerebrovascular and respiratory variables at all stages of the INDO trials are presented in Table 1. Both HR and MAP were elevated at +6 and +9 mmHg pre‐ and post‐INDO in the hypercapnic trial, while MAP was unaltered and HR was reduced at −6 and −9 mmHg during hypocapnia pre‐ and post‐INDO. There was a main effect of INDO on MAP and HR during hypercapnia, with MAP being higher post‐INDO and HR lower. In hypocapnia, HR was lower post‐INDO. There was a distinct individual variability in the MAP response (MAP increase ranged from 0 to 15 mmHg above baseline) to hypercapnia, but there was no relationship between MAP reactivity and vasomotor reactivity pre‐ (r 2 = 0.05; P = 0.53) or post‐ (r 2 = 0.05; P = 0.53) INDO. The change in MAP reactivity and vasomotor reactivity from pre‐ to post‐INDO for the hypercapnic tests were also not related (r 2 = 0.02; P = 0.73).

Table 1.

Cerebrovascular and cardiorespiratory variables before and following INDO during hyper‐ and hypocapnia

| Hypercapnia | Hypocapnia | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | +3 mmHg | +6 mmHg | +9 mmHg | Baseline | −3 mmHg | −6 mmHg | −9 mmHg | ||

| Pre vs. post: P < 0.001; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P < 0.001 | Pre vs. post: P < 0.001; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Q ICA (ml min−1) | Pre | 256.2 ± 62.9 | 299.6 ± 75.2* | 345.1 ± 94.9* | 429.5 ± 116.3* | 259.9 ± 70.3 | 224.1 ± 45.5* | 207.9 ± 42.7* | 184.7 ± 39.6* |

| Post | 163.1 ± 40.2† | 172.0 ± 40.2† | 187.4 ± 40.6† | 210.0 ± 48.0†* | 174.2 ± 40.1† | 153.1 ± 37.2† | 153.8 ± 34.0† | 151.4 ± 32.5† | |

| Pre vs. post: P < 0.001; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P < 0.001 | Pre vs. post: P = 0.002; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P < 0.001 | ||||||||

| ICAv (cm s−1) | Pre | 44.5 ± 4.4 | 49.9 ± 5.8* | 54.6 ± 5.7* | 63.2 ± 7.1* | 41.0 ± 7.9 | 36.7 ± 5.4* | 34.4 ± 4.6* | 31.3 ± 4.5* |

| Post | 31.4 ± 5.0† | 32.8 ± 5.6† | 34.9 ± 5.4† | 38.8 ± 6.5† | 33.1 ± 5.5† | 29.8 ± 5.8† | 29.9 ± 4.6† | 29.5 ± 4.2* | |

| Pre vs. post: P < 0.001; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P < 0.001 | Pre vs. post: P < 0.001; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.061 | ||||||||

| Diameter (mm) | Pre | 4.91 ± 0.53 | 4.99 ± 0.50 | 5.12 ± 0.53* | 5.31 ± 0.54* | 5.15 ± 0.45 | 5.07 ± 0.39* | 5.04 ± 0.35* | 4.97 ± 0.35* |

| Post | 4.66 ± 0.52† | 4.70 ± 0.51† | 4.76 ± 0.53† | 4.78 ± 0.51† | 4.70 ± 0.45 | 4.67 ± 0.48* | 4.65 ± 0.47* | 4.65 ± 0.51* | |

| Pre vs. post: P < 0.001; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P < 0.001 | Pre vs. post: P = 0.002; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P < 0.001 | ||||||||

| MCAv (cm s−1) | Pre | 65.8 ± 8.6 | 74.1 ± 10.4* | 82.7 ± 11.9* | 94.7 ± 13.5* | 63.7 ± 9.6 | 57.8 ± 9.0* | 53.2 ± 8.4* | 50.2 ± 7.5* |

| Post | 41.3 ± 8.0† | 44.2 ± 8.9† | 47.9 ± 11.6† | 53.1 ± 15.3† | 46.0 ± 10.7† | 43.8 ± 9.2† | 43.5 ± 9.1† | 42.3 ± 7.6† | |

| Pre vs. post : P = 0.015; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.926 | Pre vs. post : P = 0.123; CO2: P = 0.325; Interaction: P = 0.034 | ||||||||

| MAP (mmHg) | Pre | 79.1 ± 7.2 | 80.8 ± 7.5 | 84.6 ± 7.2* | 87.2 ± 8.7* | 81.4 ± 9.5 | 81.6 ± 7.7 | 84.4 ± 9.2 | 87.5 ± 7.4 |

| Post | 85.6 ± 9.8 | 87.1 ± 11.6 | 90.0 ± 9.8* | 92.9 ± 8.7* | 87.5 ± 7.4† | 86.8 ± 9.0 | 87.0 ± 10.3 | 86.8 ± 11.2 | |

| Pre vs. post: P < 0.001; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P < 0.001 | Pre vs. post: P < 0.001; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P < 0.001 | ||||||||

| CVC | Pre | 3.26 ± 0.88 | 3.55 ± 0.77* | 3.85 ± 0.88* | 4.97 ± 1.48* | 3.17 ± 0.68 | 2.74 ± 0.48* | 2.46 ± 0.40* | 2.18 ± 0.39* |

| (ml min−1 mmHg−1) | Post | 1.90 ± 0.44† | 2.01 ± 0.58† | 2.09 ± 0.47† | 2.27 ± 0.55† | 1.99 ± 0.47† | 1.76 ± 0.41† | 1.77 ± 0.40† | 1.72 ± 0.36† |

| Pre vs. post: P < 0.001; CO2: P = 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.153 | Pre vs. post: P = 0.005; CO2: P = 0.002; Interaction: P = 0.264 | ||||||||

| HR (beats min–1) | Pre | 58.6 ± 11.5 | 62.8 ± 11.1 | 65.1 ± 10.6* | 71.1 ± 10.9* | 56.6 ± 11.0 | 59.7 ± 8.8 | 61.4 ± 8.8* | 58.4 ± 9.4 |

| Post | 52.2 ± 8.3 | 53.0 ± 10.1 | 56.7 ± 9.3* | 62.0 ± 10.1* | 52.7 ± 10.2 | 55.2 ± 9.6 | 56.9 ± 10.5* | 56.0 ± 10.2 | |

| Pre vs. post : P = 0.033; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.294 | Pre vs. post: P = 0.082; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.447 | ||||||||

| VE (l min−1) | Pre | 14.3 ± 3.5 | 20.4 ± 4.2* | 28.5 ± 6.2* | 39.1 ± 8.2* | 14.3 ± 3.2 | 24.9 ± 9.1* | 26.2 ± 7.0* | 26.9 ± 7.5* |

| Post | 16.5 ± 4.8 | 22.3 ± 5.3* | 32.0 ± 8.5* | 43.8 ± 10.7* | 18.3 ± 5.4 | 25.9 ± 3.8* | 30.3 ± 6.0* | 29.7 ± 6.3* | |

| Pre vs. post: P = 0.070; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.098 | Pre vs. post: P = 0.010; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.293 | ||||||||

| (mmHg) | Pre | 40.7 ± 1.9 | 43.9 ± 1.8* | 46.6 ± 1.8* | 49.8 ± 1.7* | 40.8 ± 1.7 | 37.9 ± 1.5* | 34.8 ± 1.6* | 32.1 ± 1.3* |

| Post | 40.2 ± 1.3 | 43.0 ± 1.2* | 46.0 ± 1.1* | 49.0 ± 1.1* | 40.1 ± 1.1 | 37.1 ± 1.2* | 34.1 ± 1.2* | 30.8 ± 1.4* | |

| Pre vs. post: P = 0.763; CO2: P = 0.086; Interaction: P = 0.145 | Pre vs. post: P = 0.729; CO2: P = 0.439; Interaction: P = 0.444 | ||||||||

| (mmHg) | Pre | 96.3 ± 3.0 | 94.9 ± 1.9 | 95.1 ± 2.4 | 95.0 ± 2.2 | 95.7 ± 2.7 | 95.2 ± 3.4 | 96.2 ± 3.8 | 95.1 ± 3.1 |

| Post | 95.9 ± 4.5 | 95.9 ± 3.9 | 95.2 ± 3.5 | 95.5 ± 3.6 | 96.6 ± 4.5 | 95.5 ± 3.7 | 95.5 ± 4.1 | 96.2 ± 3.4 | |

Pre or Post in bold type indicates main effect of the intervention, with the bolded trial significantly greater. *Significant difference from baseline. †Significant interaction between pre and post. V E, expiratory tidal volume.

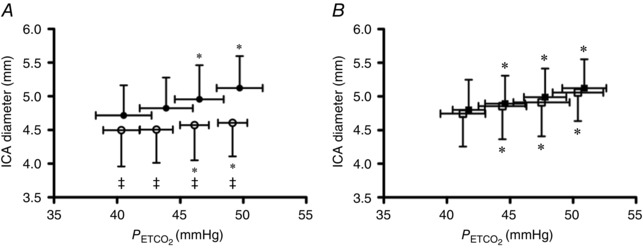

Hypercapnia increased MCAv at all stages during the pre‐INDO trial, but only at +6 and +9 mmHg during the post‐INDO trial. Similarly, MCAv was reduced at all stages during hypocapnia pre‐INDO, but only at −6 and −9 mmHg following INDO. Prior to INDO, Q ICA was elevated at all stages of hypercapnia; however, this elevation was only apparent at +9 mmHg post‐INDO. During hypocapnia, Q ICA was reduced at all stages pre‐INDO, but only at −6 and −9 mmHg following INDO. Pre‐ and post‐INDO ICA diameter was elevated at +6 and +9 mmHg (Fig. 3 A), while during hypocapnia, ICA diameter was reduced at every stage pre‐ and post‐INDO (Fig. 4 A). Pre‐INDO, CVC was elevated at all stages of hypercapnia, but only at +9 mmHg post‐INDO. During hypocapnia, CVC was reduced at all stages pre‐INDO, but did not change during the post‐INDO trial. There was a main effect of INDO on MCAv, Q ICA, ICA diameter and CVC in hypo‐ and hypercapnia, all of which were lower post‐INDO.

Figure 3. The vasomotor response to hypercapnia .

A, the vasomotor response to hypercapnia pre‐ (●) and post‐ (∘) INDO. B, the vasomotor response to hypercapnia pre‐ (▪) and post‐ (□) placebo. There was a main effect of INDO, but not placebo, on ICA diameter, which was lower following INDO. Data were analysed using a two‐way repeated measures ANOVA and post‐hoc comparisons were made using Tukey's HSD. *Different from baseline, P < 0.05; ‡between‐trial difference in diameter between baseline and intervention, P < 0.05.

Figure 4. The vasomotor response to hypocapnia .

A, the vasomotor response to hypocapnia pre‐ (●) and post‐ (∘) INDO. B, the vasomotor response to hypocapnia pre‐ (▪) and post‐ (□) placebo. There was a main effect of INDO, but not placebo, on ICA diameter, which was lower following INDO. Data were analysed using a two‐way repeated measures ANOVA and post‐hoc comparisons were made using Tukey's HSD. *Different from baseline, P < 0.05.

Placebo CO2 trials

Cardiovascular, cerebrovascular and respiratory variables at all stages of the placebo trials are presented in Table 2. During hypercapnia, MAP was elevated at all stages while HR was elevated at +6 and +9 mmHg . There was no effect of hypocapnia on MAP or HR.

Table 2.

Cerebrovascular and cardiorespiratory variables before and following Placebo during hyper and hypocapnia

| Hypercapnia | Hypocapnia | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | +3 mmHg | +6 mmHg | +9 mmHg | Baseline | −3 mmHg | −6 mmHg | −9 mmHg | ||

| Pre vs. post: P = 0.322; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.546 | Pre vs. post: P = 0.260; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.105 | ||||||||

| QICA (ml min−1) | Pre | 258.9 ± 49.1 | 310.8 ± 69.1* | 357.2 ± 73.5* | 413.1 ± 79.2* | 261.6 ± 49.4 | 237.6 ± 51.8* | 209.9 ± 49.2* | 190.8 ± 39.4* |

| Post | 263.3 ± 51.9 | 298.4 ± 56.7* | 346.0 ± 70.4* | 408.3 ± 67.8* | 261.9 ± 58.4 | 237.1 ± 46.2* | 225.2 ± 46.4* | 200.2 ± 40.3* | |

| Pre vs. Post: P = 0.521; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.348 | Pre vs. Post: P = 0.084; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.152 | ||||||||

| ICAv (cm s−1) | Pre | 44.0 ± 5.2 | 49.0 ± 4.9* | 56.1 ± 6.9* | 61.9 ± 7.7* | 40.8 ± 5.6 | 37.7 ± 4.6* | 34.2 ± 4.2* | 31.8 ± 4.2* |

| Post | 45.9 ± 7.6 | 49.5 ± 6.9* | 55.7 ± 7.7* | 62.9 ± 7.4* | 42.2 ± 4.9 | 38.9 ± 4.7* | 37.6 ± 4.6* | 34.9 ± 3.7* | |

| Pre vs. post: P = 0.160; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.815 | Pre vs. post: P = 0.335; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.467 | ||||||||

| Diameter (mm) | Pre | 4.80 ± 0.45 | 4.89 ± 0.42* | 4.99 ± 0.43* | 5.12 ± 0.43* | 5.01 ± 0.28 | 4.93 ± 0.29 | 4.87 ± 0.28* | 4.81 ± 0.22* |

| Post | 4.75 ± 0.49 | 4.85 ± 0.49* | 4.91 ± 0.50* | 5.06 ± 0.42* | 4.88 ± 0.49 | 4.84 ± 0.45 | 4.82 ± 0.41* | 4.70 ± 0.41* | |

| Pre vs. post: P = 0.221; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.636 | Pre vs. post: P = 0.873; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.595 | ||||||||

| MCAv (cm s−1) | Pre | 63.9 ± 12.8 | 69.7 ± 13.6* | 78.7 ± 15.8* | 89.1 ± 15.5* | 61.7 ± 12.6 | 55.1 ± 12.0* | 50.0 ± 11.2* | 47.5 ± 10.0* |

| Post | 60.8 ± 14.3 | 68.3 ± 15.4* | 76.6 ± 16.2* | 87.3 ± 16.5* | 61.2 ± 12.9 | 55.0 ± 11.8* | 50.7 ± 11.2* | 48.0 ± 9.1* | |

| Pre vs. post: P = 0.990; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.113 | Pre vs. post: P = 0.926; CO2: P = 0.665; Interaction: P = 0.375 | ||||||||

| MAP (mmHg) | Pre | 81.0 ± 6.8 | 82.7 ± 7.1* | 84.0 ± 7.3* | 89.0 ± 8.7* | 81.1 ± 7.0 | 81.5 ± 7.9 | 82.5 ± 8.6 | 83.8 ± 8.9 |

| Post | 78.8 ± 6.1 | 82.3 ± 9.3* | 86.4 ± 10.0* | 89.2 ± 10.9* | 82.8 ± 9.6 | 81.8 ± 6.8 | 81.1 ± 8.8 | 82.5 ± 7.7 | |

| Pre vs. post: P = 0.481; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.178 | Pre vs. post: P = 0.246; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.017 | ||||||||

| CVC | Pre | 3.21 ± 0.61 | 3.78 ± 0.88* | 4.29 ± 1.01* | 4.67 ± 0.96* | 3.21 ± 0.46 | 2.91 ± 0.54* | 2.55 ± 0.55* | 2.28 ± 0.42* |

| (ml min−1 mmHg−1) | Post | 3.37 ± 0.72 | 3.66 ± 0.79* | 4.05 ± 0.95* | 4.63 ± 0.89* | 3.17 ± 0.66 | 2.91 ± 0.58* | 2.80 ± 0.62† | 2.44 ± 0.51* |

| Pre vs. post: P = 0.671; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.486 | Pre vs. post: P = 0.067; CO2: P = 0.165; Interaction: P = 0.598 | ||||||||

| HR (beats min−1) | Pre | 58.1 ± 9.0 | 59.7 ± 8.4 | 64.1 ± 6.9* | 68.1 ± 5.9* | 55.5 ± 8.1 | 52.5 ± 19.9 | 57.1 ± 7.3 | 57.2 ± 7.8 |

| Post | 94.5 ± 3.2 | 94.0 ± 2.9 | 94.0 ± 3.0* | 93.8 ± 2.9* | 57.4 ± 10.7 | 60.3 ± 11.4 | 62.8 ± 13.7 | 63.1 ± 11.5 | |

| Pre vs. post: P = 0.338; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.912 | Pre vs. post: P = 0.607; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.230 | ||||||||

| VE (l min−1) | Pre | 14.3 ± 3.3 | 20.4 ± 4.8* | 31.1 ± 8.0* | 41.0 ± 11.1* | 16.0 ± 5.3 | 25.3 ± 8.6* | 24.9 ± 7.8* | 25.0 ± 7.9* |

| Post | 15.7 ± 4.1 | 21.9 ± 5.7* | 32.2 ± 8.1* | 41.7 ± 11.4* | 17.5 ± 5.7 | 23.5 ± 7.1* | 25.0 ± 5.9* | 27.4 ± 7.2* | |

| Pre vs. post: P = 0.188; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.415 | Pre vs. post: P = 0.666; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.537 | ||||||||

| (mmHg) | Pre | 41.7 ± 1.3 | 44.6 ± 1.6* | 47.8 ± 1.7* | 50.9 ± 1.7* | 41.7 ± 1.2 | 38.5 ± 1.4* | 35.3 ± 0.9* | 32.5 ± 1.0* |

| Post | 41.3 ± 1.8 | 44.4 ± 1.9* | 47.5 ± 2.2* | 50.4 ± 2.0* | 41.3 ± 1.5 | 38.7 ± 2.2* | 35.4 ± 2.0* | 32.8 ± 2.2* | |

| Pre vs. post: P = 0.733; CO2: P = 0.739; Interaction: P = 0.097 | Pre vs. post: P = 0.776; CO2: P = 0.383; Interaction: P = 0.236 | ||||||||

| (mmHg) | Pre | 94.1 ± 6.3 | 95.0 ± 6.5 | 95.0 ± 6.6 | 94.7 ± 6.2 | 94.4 ± 5.4 | 94.0 ± 5.1 | 92.9 ± 5.5 | 93.8 ± 4.7 |

| Post | 94.5 ± 3.2 | 94.0 ± 2.9 | 94.0 ± 3.0 | 93.8 ± 2.9 | 94.0 ± 2.9 | 94.6 ± 3.2 | 94.3 ± 3.3 | 93.9 ± 3.0 | |

Pre or Post in bold type indicates main effect of the intervention, with the bolded trial significantly greater. *Significant difference from baseline. †Significant interaction between pre and post. V E, expiratory tidal volume.

Hypercapnia increased MCAv and Q ICA at all stages pre‐ and post‐placebo, while hypocapnia decreased MCAv and Q ICA at all stages pre‐ and post‐placebo. Pre‐ and post‐placebo ICA diameter was elevated at all stages of hypercapnia (Fig. 3 B), and decreased during the −6 and −9 mmHg hypocapnic stages (Fig. 4 B). Hypercapnia increased CVC at all stages while hypocapnia decreased CVC at all stages.

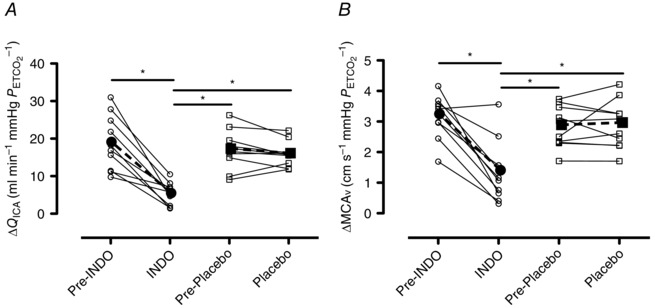

Cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity

The slope responses of Q ICA, MCAv, MAP and ventilation to changes in during the INDO and placebo trials are presented in Table 3. These variables were compared across all conditions (pre‐INDO vs. post‐INDO vs. pre‐placebo vs. post‐placebo). Absolute hypercapnic Q ICA and MCAv reactivity were reduced by 69 ± 20 and 59 ± 28% following INDO (P < 0.01 for both), respectively, and as expected were unaltered by placebo treatment (Q ICA P = 0.22; MCAv P = 0.69) (Fig. 5). For both Q ICA and MCAv, the pre‐INDO, pre‐placebo and placebo trials did not differ in their respective absolute hypercapnic reactivity. Following INDO, relative hypercapnic Q ICA and MCAv reactivity were reduced by 50 ± 33 and 38 ± 36%, respectively, but were unaltered by placebo treatment (Q ICA P = 0.32; MCAv P = 0.31). For both Q ICA and MCAv, the pre‐INDO, pre‐placebo and placebo trials did not differ in their respective relative hypercapnic reactivities.

Table 3.

Cerebrovascular and blood pressure responses to CO2 before and following INDO or placebo

| Absolute reactivity | Relative reactivity | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Units | Pre‐INDO | INDO | Pre‐Placebo | Placebo | Units | Pre‐INDO | INDO | Pre‐Placebo | Placebo | |

| Hypercapnia | ||||||||||

| QICA | (ml min−1 mmHg −1) | 18.9 ± 7.3† | 5.3 ± 3.0*† | 17.1 ± 5.3† | 15.9 ± 3.3† | (% mmHg −1) | 7.3 ± 2.0† | 3.5 ± 2.2*† | 6.7 ± 1.9† | 6.2 ± 1.2† |

| MCAv | (cm s−1 mmHg −1) | 3.2 ± 0.7† | 1.3 ± 1.0*† | 2.8 ± 0.7† | 2.9 ± 0.7† | (% mmHg −1) | 4.8 ± 0.9† | 3.0 ± 1.9*† | 4.5 ± 1.3† | 5.0 ± 1.8† |

| MAP | (mmHg mmHg −1) | 0.9 ± 0.6 | 0.8 ± 0.5 | 0.9 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.6 | (% mmHg −1) | 1.2 ± 0.8 | 1.0 ± 0.7 | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 1.5 ± 0.4 |

| VE | (l min−1 mmHg −1) | 2.7 ± 0.8 | 3.1 ± 1.0 | 3.0 ± 1.2 | 2.9 ± 1.3 | (% · mmHg −1) | 19.8 ± 6.1 | 19.9 ± 8.1 | 22.1 ± 10.6 | 19.7 ± 9.7 |

| Hypocapnia | ||||||||||

| QICA | (ml min−1 mmHg ) | 8.2 ± 4.2 | 2.2 ± 2.0* | 7.9 ± 2.2 | 6.8 ± 2.2 | (% mmHg −1) | 3.0 ± 1.0 | 1.2 ± 0.9* | 3.0 ± 0.6 | 2.6 ± 0.4 |

| MCAv | (cm s−1 mmHg −1) | 1.6 ± 0.4 | 0.4 ± 0.5* | 1.6 ± 0.4 | 1.5 ± 0.5 | (% mmHg −1) | 2.4 ± 0.5 | 0.7 ± 0.8* | 2.5 ± 0.4 | 2.4 ± 0.5 |

| MAP | (mmHg mmHg −1) | −0.4 ± 0.5 | −0.08 ± 0.6 | −0.3 ± 0.6 | −0.04 ± 0.8 | (% mmHg −1) | −0.5 ± 0.7 | −0.07 ± 0.7 | −0.4 ± 0.8 | −0.002 ± 0.9 |

*Significantly lower than pre‐INDO, P < 0.05; †significant difference between hypercapnic and hypocapnic reactivities within the experimental trial, P < 0.05. V E, expiratory tidal volume.

Figure 5. Volumetric flow and velocity cerebrovascular reactivity to hypercapnia .

A, hypercapnic Q ICA reactivity prior to and following INDO and placebo treatments. B, hypercapnic MCAv reactivity prior to and following INDO and placebo treatments. Continuous lines and open circles (∘) denote individual data, while dashed bold lines and filled circles (●) denote mean data from the INDO trial. Continuous lines and open squares (□) denote individual data, while dashed bold lines and filled squares (▪) denote mean data from the placebo trial. Differences between trials were assessed using a one‐way repeated measures ANOVA and post‐hoc tests were made using Tukey's HSD. *Significant differences between trials, P < 0.05.

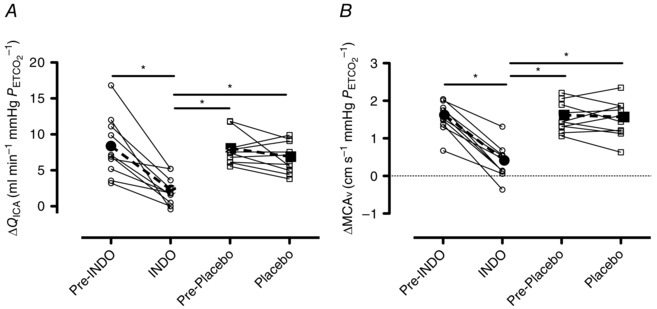

Although unchanged in the placebo trial (Q ICA P = 0.15; MCAv P = 0.63), absolute hypocapnic Q ICA and MCAv reactivity were significantly reduced by 72 ± 25 and 79 ± 25% (both P < 0.01), respectively, following INDO (Fig. 6). For both Q ICA and MCAv, the pre‐INDO, pre‐placebo and placebo trials did not differ in their respective absolute hypocapnic reactivities. Relative hypocapnic Q ICA and MCAv reactivity were reduced by 60 ± 32% (P < 0.01) and 76 ± 32% (P < 0.01), respectively, following INDO, but were unaltered following the placebo treatment (Q ICA P = 0.23; MCAv P = 0.48). For both Q ICA and MCAv, the pre‐INDO, pre‐placebo and placebo trials did not differ in their respective relative hypocapnic reactivities.

Figure 6. Volumetric flow and velocity cerebrovascular reactivity to hypocapnia .

A, hypocapnic Q ICA reactivity prior to and following INDO and placebo treatments. B, hypocapnic MCAv reactivity prior to and following INDO and placebo treatments. Continuous lines and open circles (∘) denote individual data, while dashed bold lines and filled circles (●) denote mean data from the INDO trial. Continuous lines and open squares (□) denote individual data, while dashed bold lines and filled squares (▪) denote mean data from the placebo trial. Differences between trials were assessed using a one‐way repeated measures ANOVA and post‐hoc tests were made using Tukey's HSD. *Significant differences between trials, P < 0.05.

Hypercapnic reactivity was greater than that during hypocapnia for Q ICA and MCAv during all trials (Table 3). During hypercapnia, relative Q ICA reactivity was greater than that of both ICAv (7.3 ± 2.0 vs. 3.5 ± 2.2% mmHg −1; P < 0.01) and MCAv (7.3 ± 2.0 vs. 4.8 ± 0.9% mmHg −1; P < 0.01) reactivity, which could be explained by progressive dilatation of the ICA (see Vasomotor response to CO2). There was no difference in hypocapnic Q ICA, ICAv and MCAv reactivity, probably due to a modest vasomotor reactivity to hypocapnia.

Vasomotor response of the ICA to CO2

The slope of the vasomotor response to hypercapnia was reduced by 67 ± 28% following INDO (0.045 ± 0.015 vs. 0.015 ± 0.012 mm mmHg −1; P < 0.01) but was unaffected by placebo (0.036 ± 0.006 vs. 0.033 ± 0.006 mm mmHg −1; P = 0.25). No change in the slope of the response to hypocapnia occurred following INDO (0.019 ± 0.015 vs. 0.006 ± 0.008 mm mmHg −1; P = 0.08). Vasomotor reactivity was greater during hypercapnia as compared to hypocapnia (0.045 ± 0.015 vs. 0.019 ± 0.015 mm mmHg −1; P < 0.01).

Study 2: ketorolac trials

Resting CBF and cardiorespiratory variables

Administration of ketorolac had no effect on resting ventilation (11.3 ± 1.5 vs. 11.8 ± 1.9 l min−1; P = 0.65), MAP (79.2 ± 8.6 vs. 80.0 ± 5.9 mmHg; P = 0.79), HR (55.1 ± 12.5 vs. 53.9 ± 14.6 beats min−1; P = 0.54), Q ICA (282.8 ± 66.7 vs. 295.6 ± 80.3 ml min−1; P = 0.38) or MCAv (56.5 ± 13.3 vs. 58.3 ± 8.1 cm s−1; P = 0.54).

Ketorolac CO2 trials

Cardiovascular, cerebrovascular and respiratory variables at all stages of the placebo trials are presented in Table 4. During hypercapnia, MAP and HR were elevated at +6 and +9 mmHg pre‐ and post‐ketorolac. There was no effect of hypocapnia on MAP while HR was elevated at all stages of hypocapnia pre‐ and post‐ketorolac.

Table 4.

Cerebrovascular and cardiorespiratory variable before and following Ketorolac during hyper and hypocapnia

| Hypercapnia | Hypocapnia | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | +3 mmHg | +6 mmHg | +9 mmHg | Baseline | −3 mmHg | −6 mmHg | −9 mmHg | |||

| Pre vs. post: P = 0.534; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.460 | Pre vs. post: P = 0.850; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.439 | |||||||||

| QICA (ml min−1) | Pre | 299.9 ± 76.3 | 346.1 ± 96.9 | 364.9 ± 103.3* | 449.3 ± 133.9* | 284.9 ± 66.7 | 261.1 ± 68.2 | 228.5 ± 62.0* | 215.7 ± 54.7* | |

| Post | 303.2 ± 76.6 | 348.1 ± 95.2 | 399.3 ± 114.1* | 452.9 ± 136.9* | 282.5 ± 83.6 | 254.4 ± 58.7 | 236.9 ± 64.8* | 223.2 ± 55.4* | ||

| Pre vs. post: P = 0.848; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.632 | Pre vs. post: P = 0.791; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.299 | |||||||||

| ICAv (cm s−1) | Pre | 47.1 ± 6.6 | 53.3 ± 7.7* | 55.8 ± 10.2* | 64.1 ± 11.9* | 43.2 ± 5.8 | 40.8 ± 5.5 | 36.4 ± 5.7* | 34.8 ± 2.9* | |

| Post | 46.7 ± 6.9 | 53.4 ± 8.9* | 58.6 ± 10.6* | 63.9 ± 11.8* | 42.1 ± 8.2 | 39.0 ± 3.8 | 36.9 ± 5.7* | 35.2 ± 4.6* | ||

| Pre vs. post: P = 0.354; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.074 | Pre vs. post: P = 0.490; CO2: P = 0.032; Interaction: P = 0.767 | |||||||||

| Diameter (mm) | Pre | 5.15 ± 0.50 | 5.18 ± 0.55 | 5.21 ± 0.51 | 5.38 ± 0.57* | 5.25 ± 0.48 | 5.14 ± 0.50 | 5.11 ± 0.53 | 5.06 ± 0.52* | |

| Post | 5.18 ± 0.42 | 5.20 ± 0.42 | 5.31 ± 0.47 | 5.41 ± 0.52* | 5.26 ± 0.42 | 5.21 ± 0.42 | 5.14 ± 0.41 | 5.11 ± 0.37* | ||

| Pre vs. post: P = 0.224; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.114 | Pre vs. post: P = 0.971; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.100 | |||||||||

| MCA (cm s−1) | Pre | 57.0 ± 9.9 | 63.2 ± 9.7* | 70.6 ± 12.3* | 79.3 ± 14.2* | 54.6 ± 9.4 | 49.5 ± 7.3* | 46.5 ± 6.1* | 43.6 ± 5.0* | |

| Post | 59.0 ± 8.8 | 64.1 ± 9.1* | 75.51 ± 10.0* | 83.0 ± 11.8* | 58.0 ± 8.2 | 49.3 ± 10.2* | 44.5 ± 10.7* | 42.7 ± 10.3* | ||

| Pre vs. post: P = 0.864; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.193 | Pre vs. post: P = 0.281; CO2: P = 0.117; Interaction: P = 0.814 | |||||||||

| MAP (mmHg) | Pre | 80.9 ± 8.5 | 82.4 ± 8.9 | 85.1 ± 10.5* | 90.4 ± 11.3* | 81.4 ± 8.2 | 80.9 ± 7.5 | 83.1 ± 7.2 | 84.9 ± 6.9 | |

| Post | 81.3 ± 9.4 | 83.1 ± 10.1 | 87.7 ± 11.8* | 88.3 ± 11.5* | 84.0 ± 10.2 | 83.3 ± 9.8 | 84.9 ± 8.9 | 85.6 ± 9.0 | ||

| Pre vs. post: P = 0.557; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.731 | Pre vs. post: P = 0.366; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.339 | |||||||||

| CVC (ml min−1 mmHg−1) | Pre | 3.71 ± 0.92 | 4.20 ± 1.16 | 4.28 ± 1.12* | 4.91 ± 1.15* | 3.49 ± 0.67 | 3.23 ± 0.81 | 2.74 ± 0.64* | 2.53 ± 0.57* | |

| Post | 3.71 ± 0.71 | 4.18 ± 1.00 | 4.53 ± 1.07* | 5.10 ± 1.35* | 3.36 ± 0.94 | 3.05 ± 0.61 | 2.76 ± 0.58* | 2.60 ± 0.56* | ||

| Pre vs. post: P = 0.359; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.518 | Pre vs. post: P = 0.149; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.151 | |||||||||

| HR (beats min−1) | Pre | 56.1 ± 13.4 | 59.0 ± 11.5 | 59.2 ± 13.1* | 62.7 ± 11.8* | 52.9 ± 14.6 | 57.6 ± 13.2* | 56.0 ± 14.9* | 54.8 ± 14.6* | |

| Post | 53.8 ± 13.8 | 56.7 ± 13.3 | 60.0 ± 11.8* | 62.6 ± 11.4* | 53.7 ± 14.8 | 57.5 ± 14.3* | 57.0 ± 14.3* | 57.6 ± 14.0* | ||

| Pre vs. post: P = 0.293; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.727 | Pre vs. post: P = 0.508; CO2: P = 0.010; Interaction: P = 0.451 | |||||||||

| VE (l min−1) | Pre | 12.5 ± 2.8 | 17.6 ± 5.1 | 25.1 ± 9.1 | 37.7 ± 17.3* | 13.3 ± 3.9 | 30.0 ± 7.9* | 30.3 ± 9.0 | 32.8 ± 9.8* | |

| Post | 14.3 ± 3.2 | 18.1 ± 7.4 | 28.1 ± 13.2 | 40.0 ± 18.6* | 14.9 ± 2.8 | 42.6 ± 29.1* | 30.5 ± 6.4 | 31.02 ± 8.7* | ||

| Pre vs. post: P = 0.368; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.014 | Pre vs. post: P = 0.267; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.472 | |||||||||

| (mmHg) | Pre | 40.57 ± 3.1 | 43.3 ± 3.0* | 46.0 ± 3.0* | 49.1 ± 2.9* | 40.1 ± 3.2 | 37.0 ± 3.2* | 34.0 ± 3.3* | 31.1 ± 3.2* | |

| Post | 39.8 ± 3.5† | 42.4 ± 3.4* | 46.2 ± 3.1* | 49.1 ± 3.5* | 39.8 ± 3.4 | 36.9 ± 3.4* | 33.7 ± 3.5* | 30.8 ± 3.3* | ||

| Pre vs. post: P = 0.502; CO2: P = 0.680; Interaction: P = 0.654 | Pre vs. post: P = 0.493; CO2: P = 0.734; Interaction: P = 0.578 | |||||||||

| (mmHg) | Pre | 97.5 ± 6.8 | 98.2 ± 6.6 | 97.8 ± 6.5 | 97.8 ± 6.5 | 97.6 ± 6.0 | 97.9 ± 6.7 | 97.9 ± 6.8 | 97.6 ± 7.0 | |

| Post | 96.9 ± 6.1 | 96.3 ± 5.1 | 96.6 ± 4.3 | 96.9 ± 4.9 | 96.9 ± 4.9 | 96.5 ± 4.9 | 96.9 ± 5.1 | 96.5 ± 4.9 | ||

There was no main effect of ketorolac on any variable. *Significant difference from baseline. ‡Significant interaction between pre and post. V E, expiratory tidal volume.

Hypercapnia increased MCAv at all stages pre‐ and post‐ketorolac, while hypocapnia decreased MCAv at all stages pre‐ and post‐ketorolac. Pre‐ and post‐ketorolac Q ICA was elevated at +6 and +9 mmHg and reduced at −6 and −9 mmHg during hypercapnia and hypocapnia, respectively. ICA diameter was elevated at +9 mmHg during hypercapnia and reduced at −9 mmHg during hypocapnia. During hypercapnia, CVC was increased at +6 and +9 mmHg , and was decreased during hypocapnia (at −6 and −9 mmHg )

Following ketorolac there was no change in absolute Q ICA or MCAv reactivity during both hypercapnia and hypocapnia (Table 5). Relative reactivity for Q ICA and MCAv did not differ before and after ketorolac either. The vasomotor response of the ICA to both hypercapnia (0.026 ± 0.015 vs. 0.026 ± 0.022 mm mmHg −1; P = 0.99) and hypocapnia (0.020 ± 0.024 vs. 0.017 ± 0.014 mm mmHg −1; P = 0.73) was unchanged following ketorolac.

Table 5.

Cerebrovascular and blood pressure responses to CO2 before and following ketorolac

| Absolute reactivity | Relative reactivity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Units | Pre‐ketorolac | Ketorolac | Units | Pre‐ketorolac | Ketorolac | |

| Hypercapnia | ||||||

| QICA | (ml min−1 mmHg −1) | 16.6 ± 8.6† | 16.2 ± 8.5† | (% mmHg −1) | 5.5 ± 2.5 | 5.2 ± 2.0† |

| MCAv | (cm s−1 mmHg −1) | 2.6 ± 0.6† | 2.7 ± 0.6† | (% mmHg −1) | 4.6 ± 0.7† | 4.6 ± 1.2† |

| MAP | (mmHg mmHg −1) | 1.1 ± 0.7† | 0.8 ± 0.5† | (%mmHg −1) | 1.4 ± 0.9† | 1.0 ± 0.5† |

| VE | (l min−1 mmHg −1) | 3.0 ± 2.0 | 2.8 ± 1.7 | (% mmHg −1) | 23.7 ± 13.9 | 19.0 ± 9.6 |

| Hypocapnia | ||||||

| QICA | (ml min−1 mmHg −1) | 8.0 ± 2.1 | 6.5 ± 4.0 | (% mmHg −1) | 2.8 ± 0.7 | 2.2 ± 0.9 |

| MCAv | (cm s−1 mmHg −1) | 1.2 ± 0.6 | 1.7 ± 0.7 | (% mmHg −1) | 2.1 ± 0.8 | 2.9 ± 1.4 |

| MAP | (mmHg mmHg −1) | −0.4 ± 0.3 | −0.2 ± 0.4 | (% mmHg −1) | −0.5 ± 0.3 | −0.3 ± 0.5 |

†Significant difference between hypercapnic and hypocapnic reactivities within an experimental trial, P < 0.05. V E, expiratory tidal volume.

Study 3: naproxen trials

Resting cerebral blood flow and cardiorespiratory variables

Administration of naproxen caused a slight increase in resting ventilation (10.3 ± 1.6 vs. 12.0 ± 1.8 l min−1; P = 0.04), while MAP (77.1 ± 4.0 vs. 74.7 ± 4.4 mmHg; P = 0.52), HR (56.1 ± 7.5 vs. 56.1 ± 8.4 beats min−1; P = 0.99), Q ICA (265.6 ± 43.5 vs. 251.1 ± 35.5 ml min−1; P = 0.38) and MCAv (56.5 ± 9.0 vs. 54.0 ± 8.5 cm s−1; P = 0.54) were unchanged.

Naproxen CO2 trials

Cardiovascular, cerebrovascular and respiratory variables at all stages of the placebo trials are presented in Table 6. During hypercapnia, MAP was elevated at +9 mmHg and HR was elevated at +6 and +9 mmHg . There was no effect of hypocapnia on MAP while HR was elevated at −9 mmHg of the pre‐naproxen trial.

Table 6.

Cerebrovascular and cardiorespiratory variables before and following Naproxen during hyper and hypocapnia

| Hypercapnia | Hypocapnia | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | +3 mmHg | +6 mmHg | +9 mmHg | Baseline | −3 mmHg | −6 mmHg | −9 mmHg | ||

| Pre vs. post: P = 0.710; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.276 | Pre vs. post: P = 0.276; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.127 | ||||||||

| QICA (ml min−1) | Pre | 277.67 ± 53.45 | 308.44 ± 41.18* | 400.49 ± 81.82* | 468.87 ± 78.80* | 269.23 ± 31.17 | 245.91 ± 31.75 | 211.66 ± 25.84* | 195.48 ± 24.42* |

| Post | 271.45 ± 52.39 | 325.67 ± 66.86* | 388.25 ± 79.00* | 459.64 ± 92.25* | 267.59 ± 48.09 | 260.39 ± 43.68 | 237.43 ± 56.30* | 222.89 ± 55.85* | |

| Pre vs. post: P = 0.918; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.344 | Pre vs. post: P = 0.155; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.261 | ||||||||

| ICAv (cm s−1) | Pre | 47.33 ± 4.17 | 51.44 ± 4.24* | 62.92 ± 7.45* | 72.43 ± 7.47* | 43.21 ± 4.44 | 40.19 ± 2.63* | 36.17 ± 3.11* | 33.25 ± 3.89* |

| Post | 46.98 ± 3.84 | 53.99 ± 4.86* | 61.51 ± 4.88* | 71.28 ± 7.92* | 43.60 ± 2.94 | 42.37 ± 1.93* | 38.86 ± 3.80* | 37.65 ± 4.17* | |

| Pre vs. post: P = 0.282; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.663 | Pre vs. post: P = 0.929; CO2: P = 0.195; Interaction: P < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Diameter (mm) | Pre | 4.97 ± 0.41 | 5.03 ± 0.37* | 5.16 ± 0.40* | 5.23 ± 0.40* | 5.14 ± 0.33 | 5.07 ± 0.43 | 4.98 ± 0.48 | 4.99 ± 0.49 |

| Post | 4.91 ± 0.39 | 5.02 ± 0.43* | 5.14 ± 0.43* | 5.20 ± 0.41* | 5.06 ± 0.36 | 5.08 ± 0.42 | 5.05 ± 0.51 | 4.97 ± 0.51 | |

| Pre vs. post: P = 0.431; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.852 | Pre vs. post: P = 0.915; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.553 | ||||||||

| MCAv (cm s−1) | Pre | 57.44 ± 10.26 | 62.75 ± 13.28* | 70.00 ± 11.71* | 81.80 ± 13.17* | 55.88 ± 8.15 | 51.85 ± 6.77* | 45.66 ± 6.65* | 43.74 ± 6.29* |

| Post | 55.60 ± 8.58 | 62.07 ± 12.33* | 68.08 ± 13.48* | 79.26 ± 16.40* | 55.30 ± 8.31 | 50.83 ± 7.29* | 47.28 ± 8.71* | 44.63 ± 7.19* | |

| Pre vs. post: P = 0.954; CO2: P0.014; Interaction: P = 0.069 | Pre vs. post: P = 0.237; CO2: P = 0.817; Interaction: P = 0.121 | ||||||||

| MAP (mmHg) | Pre | 76.82 ± 6.81 | 77.75 ± 4.48 | 80.26 ± 5.54 | 84.71 ± 5.61* | 78.54 ± 2.41 | 78.08 ± 4.29 | 75.64 ± 3.83 | 78.18 ± 2.69 |

| Post | 78.01 ± 5.04 | 81.28 ± 3.99 | 79.79 ± 3.87 | 81.05 ± 3.80* | 74.25 ± 3.70 | 75.97 ± 4.10 | 77.88 ± 2.42 | 77.29 ± 2.95 | |

| Pre vs. post: P = 0.998; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.444 | Pre vs. post: P = 0.154; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.754 | ||||||||

| CVC | Pre | 3.59 ± 0.37 | 3.95 ± 0.32* | 4.96 ± 0.69* | 5.52 ± 0.66* | 3.43 ± 0.34 | 3.15 ± 0.42 | 2.80 ± 0.37* | 2.50 ± 0.28* |

| (ml min−1 mmHg−1) | Post | 3.50 ± 0.80 | 4.01 ± 0.83* | 4.86 ± 0.89* | 5.66 ± 1.00* | 3.59 ± 0.50 | 3.44 ± 0.60 | 3.06 ± 0.77* | 2.90 ± 0.82* |

| Pre vs. post: P = 0.998; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.398 | Pre vs. post: P = 0.790; CO2: P < 0.041; Interaction: P = 0.024 | ||||||||

| HR (beats min−1) | Pre | 55.09 ± 7.56 | 58.26 ± 8.10 | 64.39 ± 8.78* | 67.85 ± 12.74* | 53.23 ± 9.30 | 55.94 ± 8.56 | 54.52 ± 8.69 | 57.58 ± 10.12* |

| Post | 55.59 ± 8.59 | 58.95 ± 8.44 | 62.50 ± 8.70* | 68.51 ± 10.55* | 54.53 ± 9.30 | 55.17 ± 8.78 | 56.20 ± 8.36 | 56.46 ± 8.53 | |

| Pre vs. post: P = 0.752; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.474 | Pre vs. post: P = 0.760; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.156 | ||||||||

| VE (l min−1) | Pre | 11.80 ± 1.90 | 21.02 ± 6.39 | 32.77 ± 11.35* | 42.99 ± 11.39* | 13.27 ± 1.77 | 25.62 ± 6.74* | 24.23 ± 4.70* | 27.06 ± 5.43* |

| Post | 14.97 ± 2.84 | 23.91 ± 7.42 | 30.85 ± 11.90* | 43.20 ± 16.81* | 14.78 ± 3.32 | 26.49 ± 6.64* | 30.97 ± 4.22* | 30.19 ± 4.13* | |

| Pre vs. post: P = 0.163; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.221 | Pre vs. post: P = 0.293; CO2: P < 0.001; Interaction: P = 0.304 | ||||||||

| (mmHg) | Pre | 41.20 ± 1.78 | 44.52 ± 1.54* | 48.03 ± 1.73* | 51.19 ± 1.81* | 41.19 ± 2.07 | 38.43 ± 1.83* | 35.50 ± 1.84* | 33.03 ± 1.54* |

| Post | 41.01 ± 1.50 | 44.26 ± 1.68* | 47.31 ± 1.82* | 50.43 ± 1.76* | 41.06 ± 1.73 | 38.79 ± 1.56* | 36.13 ± 1.73* | 33.40 ± 1.72* | |

| Pre vs. post: P = 0.405; CO2: P = 0.039; Interaction: P = 0.220 | Pre vs. post: P = 0.827; CO2: P = 0.003; Interaction: P = 0.134 | ||||||||

| (mmHg) | Pre | 94.58 ± 2.78 | 95.14 ± 2.24 | 94.46 ± 2.30 | 93.26 ± 2.41 | 95.30 ± 2.17 | 94.42 ± 2.93 | 93.30 ± 3.22* | 92.52 ± 2.44* |

| Post | 95.70 ± 2.58 | 95.10 ± 2.83 | 95.11 ± 3.4 | 94.71 ± 2.97 | 98.38 ± 5.52 | 93.80 ± 3.04 | 92.33 ± 2.75* | 92.07 ± 2.87* | |

There was no main effect of naproxen on any variable. *Significant difference from baseline. †Significant interaction between pre and post. V E, expiratory tidal volume.

Hypercapnia increased MCAv at all stages pre‐ and post‐naproxen, while hypocapnia decreased MCAv at all stages pre‐ and post‐Naproxen. Pre‐ and post‐Naproxen Q ICA was elevated at all stages of hypercapnia and reduced at −6 and −9 mmHg during hypocapnia. ICA diameter was elevated at all stages of hypercapnia but was not significantly reduced at any stage of hypocapnia. During hypercapnia CVC was increased at all stages and was reduced during hypocapnia at −6 and −9 mmHg .

Following naproxen there was no change in absolute Q ICA or MCAv reactivity during both hypercapnia and hypocapnia (Table 7). Relative reactivity for Q ICA and MCAv also did not differ before and after naproxen. The vasomotor response of the ICA to both hypercapnia (0.030 ± 0.010 vs. 0.032 ± 0.005 mm mmHg −1; P = 0.81) and hypocapnia (0.018 ± 0.026 vs. 0.011 ± 0.025 mm mmHg −1; P = 0.06) was unchanged following naproxen.

Table 7.

Cerebrovascular and blood pressure responses to CO2 before and following naproxen

| Absolute reactivity | Relative reactivity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Units | Pre‐naproxen | Naproxen | Units | Pre‐naproxen | Naproxen | |

| Hypercapnia | ||||||

| QICA | (ml min−1 mmHg −1) | 19.9 ± 3.2 | 19.9 ± 3.5 | (% mmHg −1) | 7.2 ± 0.7 | 7.4 ± 1.1 |

| MCAv | (cm s−1 mmHg −1) | 2.3 ± 0.6 | 2.0 ± 0.7 | (% mmHg −1) | 4.3 ± 1.1 | 4.1 ± 1.0 |

| MAP | (mmHg mmHg −1) | 0.8 ± 0.4 | 0.2 ± 0.6 | (% mmHg −1) | 1.1 ± 0.6 | 0.3 ± 0.9 |

| VE | (l min−1 mmHg −1) | 3.1 ± 1.1 | 2.9 ± 1.6 | (% mmHg −1) | 28.6 ± 1.8 | 18.9 ± 7.8† |

| Hypocapnia | ||||||

| QICA | (ml min−1 mmHg −1) | 9.3 ± 3.7 | 6.0 ± 1.9 | (% mmHg −1) | 3.4 ± 1.1 | 2.3 ± 0.9 |

| MCAv | (cm s−1 mmHg −1) | 1.6 ± 0.4 | 1.1 ± 0.4 | (% mmHg −1) | 2.8 ± 0.5 | 2.7 ± 0.7 |

| MAP | ( mmHg mmHg −1) | 0.2 ± 0.5 | −0.4 ± 0.8 | (% mmHg −1) | 0.2 ± 0.7 | −0.6 ± 1.1 |

†Significant difference between hypercapnic and hypocapnic reactivities within an experimental trial, P < 0.05. V E, expiratory tidal volume.

Discussion

The primary novel findings of this study were: (1) the ICA dilatates in response to hypercapnia and modestly constricts in response to hypocapnia; (2) vasomotion of the ICA in response to hypercapnia is markedly blunted (−67%) following INDO administration; and (3) INDO, but not ketorolac or naproxen, inhibits cerebrovascular responses to CO2, indicating a permissive (i.e. non‐COX inhibition‐mediated) effect(s) of INDO.

Cerebrovascular responses to CO2

Our volumetric blood flow data have revealed similar hypercapnic reactivity values to that first collected using the (Kety & Schmidt, 1948) technique of ∼7–8% mmHg −1; such values are consistent with recent studies (Willie et al. 2012; Hoiland et al. 2015; Tymko et al. 2016). This volumetric reactivity, during hypercapnia, greatly exceeds that recorded using TCD measures of MCAv in the current and previous studies (e.g. Ide et al. 2003, 2007; Willie et al. 2012; Regan et al. 2014; Brothers et al. 2014; Hoiland et al. 2015). As relative MCAv and ICAv reactivity to hypercapnia did not differ, this indicates that vasomotion is responsible for the difference between volumetric flow and velocity indices of cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity. Consistent with this finding are recent reports that the MCA dilatates in response to hypercapnia (Verbree et al. 2014; Coverdale et al. 2014, 2015) leading to consequent underestimation of cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity with velocity measures (Ainslie & Hoiland, 2014).

The vasomotor response of the ICA to hypercapnia was markedly greater than that during hypocapnia; thus, there was no appreciable difference in volumetric and velocity indices of reactivity in the hypocapnic range. Upon close examination of the vasomotor profile of the ICA during changes in , it is quite similar to the expected vasomotor profile of the MCA diameter (see fig. 1 in Ainslie & Hoiland, 2014), wherein small changes in do not elicit measurable changes in diameter (Verbree et al. 2014; Coverdale et al. 2014). It seems that a larger hypocapnic stimulus (e.g. ∼9 mmHg below baseline) is required to elicit constriction than the necessary hypercapnic stimulus for dilatation, probably a function of the overall lower cerebrovascular reactivity during hypocapnia. However, using our experimental approach (see Comparison between studies below for an explanation) it appears that the ICA may be more sensitive to changes in CO2 in the hypercapnic range as dilatation at +3 mmHg was observed in both the pre‐ and post‐placebo trials, while the MCA does not appear to dilatate (as measured using 3‐T magnetic resonance imaging) until approximately +9 mmHg (Coverdale et al. 2014).

Comparisons between studies

Conflicting data exist as to whether CO2‐mediated vasomotion of the ICA does (Willie et al. 2012; Hoiland et al. 2014) or does not occur (Coverdale et al. 2015). The present study aimed to resolve these conflicting data, and corroborates the data exemplifying that vasomotion of the ICA does occur. Differences between studies are probably due to several methodological and analytical differences. These differences include the method of manipulating , and determination of vessel diameter. For example, Coverdale et al. (2015) utilized elevations in fractional inspired CO2 (0.06) to elicit a ∼10 mmHg increase in . This technique is limited in that tends to overestimate by ∼4–6 mmHg at this level of hypercapnia (Peebles et al. 2007). In contrast, our approach of end‐tidal forcing results in over‐estimating by only ∼1–2 mmHg (Tymko et al. 2015, 2016). Therefore, it is possible that the hypercapnic (not ) stimulus applied by Coverdale et al. (2015) was only around ∼5–6 mmHg above baseline whereas the stimulus in the current study is representative of the true stimulus (Tymko et al. 2016). As the current study shows very modest changes in diameter with mild hypercapnia, this provides an explanation, in part, for the lack of ICA dilatation observed by Coverdale et al. (2015). Second, discrepancies between studies may be a reflection of the use of caliper‐based manual diameter measures (quantified over three cardiac cycles) rather than our automated approach (quantified over a minimum of 12 consecutive cardiac cycles). The latter approach is affected less by artifacts, and by the potential influences of respiration and blood pressure variability. As such, using edge‐detection software not only provides a more robust and sensitive assessment of vessel diameter and velocity (Woodman et al. 2001), it also limits subjectivity and bias during data analysis (see Methods for details).

COX inhibition

It has been previously established that the dose of INDO in the current study is sufficient to effectively inhibit PG synthesis (Eriksson et al. 1983). Inhibition of COX with INDO resulted in a significant reduction in both resting CBF and cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity in both the hypo‐ and the hyper‐capnic range. This result is in agreement with previous studies using various measurement techniques to quantify CBF (Wennmalm et al. 1981; Bruhn et al. 2001; St Lawrence et al. 2002; Xie et al. 2006; Hoiland et al. 2015). However, COX inhibition with ketorolac and naproxen did not affect resting CBF, cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity or the vasomotor responsiveness of the ICA. Some previous data, comparing INDO to other COX inhibitors, have indicated that INDO reduces CBF and cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity via a ‘COX inhibition independent’ mechanism (Eriksson et al. 1983; Markus et al. 1994); however, these studies provided limited suggestion of alternative mechanisms and did not directly assess cerebral artery vasomotion. On the basis of previous studies in vitro and in highly controlled animal models, we reason here that the selectivity of INDO is related to either the inhibition of cAMP‐dependent protein kinase (Kantor & Hampton, 1978; Goueli & Ahmed, 1980), inhibition of PG (i.e. prostacyclin) receptor binding‐mediated increases in vascular smooth muscle cAMP (Parfenova et al. 1995) or both (see Pharmacological interventions below). Thus, it appears PGs may not play an appreciable (or detectable) role in the regulation of extra‐cranial cerebral artery vasomotion during alterations in .

Pharmacological interventions

Several factors have supported INDO as a useful pharmacological agent to assess the effects of COX inhibition on CBF: cardiac output is minimally affected by the administration of INDO (Nowak & Wennmalm, 1978; Wennmalm et al. 1984) and INDO does not appear to alter cerebral metabolism (Kraaier et al. 1992), resting ventilation (Hoiland et al. 2015), peripheral chemosensitivity (Xie et al. 2006) or plasma catecholamines (Staessen et al. 1984; Green et al. 1987). Thus, INDO has been extensively used to assess the influence of PG on cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity (Wennmalm et al. 1981; Eriksson et al. 1983; Bruhn et al. 2001; St Lawrence et al. 2002) in addition to many other experimental paradigms. That other COX‐inhibiting drugs such as aspirin and naproxen (Eriksson et al. 1983; Markus et al. 1994) yield divergent findings compared to INDO, however, suggests that INDO reduces cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity through a PG‐independent mechanism. Yet, it is still continually used to assess PG‐mediated responses. For example, extremely low doses of INDO have been reported to inhibit cAMP‐dependent protein kinase activity (Kantor & Hampton, 1978; Goueli & Ahmed, 1980). As illustrated in Fig. 1, this inhibition will directly affect vascular smooth muscle cell calcium sensitivity (Adelstein & Conti, 1978), and thus vasomotor tone (Kerrick & Hoar, 1981). Moreover, in newborn pigs, which also demonstrate reductions in resting CBF and cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity to INDO but not other COX inhibitors (e.g. aspirin, ibuprofen, naproxen; Chemtob et al. 1991), INDO blocks prostacyclin receptor‐mediated signal transduction during hypercapnia (Parfenova et al. 1995), specifically downstream increases in cAMP (see Fig. 1). However, aspirin does not inhibit prostacyclin receptor‐mediated signalling and subsequent increases in smooth muscle cell cAMP (Parfenova et al. 1995), highlighting that this is a unique effect of INDO. Therefore, although the primary purpose of this study was to characterize the effect of INDO on CO2‐mediated vasomotor responses of the ICA, we also aimed to test the effect of ketorolac and naproxen on such vasomotor responses. These additional drug interventions were used to determine if INDO acts differently from other COX inhibitors in its ability to blunt CO2‐mediated vasomotion (in addition to flow reactivity) of large extra‐cranial cerebral arteries. With ketorolac and naproxen we showed no difference in the vasomotor response (i.e. magnitude of dilatation), consistent with the lack of reductions in flow and velocity reactivity observed in previous studies (Eriksson et al. 1983; Markus et al. 1994), indicating that INDO is affecting the vasomotor tone of larger cerebral arteries in a permissive (i.e. independent of COX inhibition) manner.

The possibility remains that only low levels of PG are required to induce vasomotion (through downstream increases in cAMP) during CO2 perturbations. This provides an explanation for the lack of effect of COX inhibitors – with the exception of INDO – on cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity, consistent with the lack of detectable levels of PG during hypercapnia (Eriksson et al. 1983). For example, near complete inhibition of PG synthesis with aspirin does not inhibit PG receptor agonism (i.e. via iloprost) or hypercapnia‐mediated increases in cAMP and vascular diameter in newborn pigs (Parfenova et al. 1995). If large doses of PGs were necessary to produce dilatation one may expect a dose‐dependent relationship between prostacyclin receptor agonism and vasodilatation; however, this is not the case during hypercapnia (Leffler et al. 1999). Collectively, these data provide a possible explanation (i.e. inhibition of prostacyclin receptor‐mediated signal transduction) as to how INDO inhibits cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity both independent of COX inhibition and in a manner unique from other COX inhibitors.

Limitations

It should be acknowledged that the use of CVC does not account for the complicated interactions of CO2‐induced MAP and vasomotor changes. In keeping with this, in the current study the increase in MAP during hypercapnia poses as a potential confound to the flow and vasomotor response of the ICA (Willie et al. 2012; Regan et al. 2014). As the MAP increase between trials (i.e. pre‐ vs. post‐INDO) was not different and there was no interaction effect between MAP and INDO (Table 1) it is quite unlikely that MAP is a contributing factor to the reduced vasomotion observed post‐INDO. However, the influence of MAP in the regulation of CBF during hypercapnia still warrants consideration. Increases in MAP will increase CBF through direct pressure effects (Lucas et al. 2010; Numan et al. 2014) despite activation of autoregulatory mechanisms aimed to counteract MAP‐induced increases in perfusion (Fog, 1939; Kontos et al. 1978). While this study did not assess potential autoregulatory effects, it is possible that pressure‐induced vasoconstriction may have, to some extent, counteracted CO2‐induced vasodilatation leading to underestimation of ICA vasomotion in all trials.

Implications

For the last 30 years, assessment of cerebrovascular responses has been dominated by the use of TCD. However, assessment of CO2 reactivity with TCD operates on the assumption (also its primary limitation) that the diameter of the MCA does not change in response to CO2 – an assumption previously thought to be true (Serrador et al. 2000). Recently, studies using higher resolution magnetic resonance imaging (Verbree et al. 2014; Coverdale et al. 2014, 2015) have reported MCA vasomotion in response to changes in CO2 and consequent underestimation of reactivity by TCD measures of velocity. Other studies assessing volumetric flow reactivity through the extra‐cranial cerebral arteries (Willie et al. 2012; Hoiland et al. 2015) provide further evidence that TCD is limited in its ability to accurately measure cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity.

Reduced cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity is indicative of an increased risk for all‐cause and cardiovascular (inclusive of stroke) mortality (Portegies et al. 2014). As it seems that changes in diameter can contribute to nearly half of the increase in flow observed during elevations in , we speculate that the magnitude of the vasomotor response (i.e. diameter change) in response to perturbations may be indicative of cerebrovascular health (i.e. endothelial function), much like peripheral flow‐mediated dilatation is indicative of cardiovascular risk (Inaba et al. 2010; Green et al. 2011). The incorporation of diameter measures into the prediction of cerebrovascular events and related mortality should be considered.

While INDO is exemplary in its ability to reduce cerebrovascular reactivity, and is thus an attractive tool for the assessment of physiological function associated with cerebrovascular reactivity (i.e. control of breathing; Xie et al. 2006; Hoiland et al. 2015), its utility for investigating the role of PG in mediating cerebrovascular responses should be cautioned. As we and others (Eriksson et al. 1983; Markus et al. 1994) have identified, INDO reduces cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity and CO2‐mediated vasomotion in a manner that is unique from other COX inhibitors. It is clear that INDO is acting in a PG‐independent manner, probably through the inhibition of cAMP‐dependent protein kinase (Kantor & Hampton, 1978; Goueli & Ahmed, 1980), and reductions in PG receptor‐mediated increases in smooth muscle cAMP (Parfenova et al. 1995) to affect cerebrovascular reactivity to CO2.

Conclusions

We demonstrate significant vasodilatation and vasoconstriction of the ICA during alterations in . Moreover, this study demonstrates that INDO reduces the vasomotor response of the ICA to changes in and provides evidence that it is independent of COX inhibition. Future studies should aim to determine the mechanism(s) underlying INDO's unique ability to reduce CO2‐mediated cerebrovascular vasomotion and to determine other regulatory mechanisms governing cerebrovascular vasomotion in healthy humans.

Additional information

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

Author contributions

Conception and design of experiments: R.L.H., P.N.A. Data collection: R.L.H., M.M.T., K.W.W., A.R.B., B.M., P.N.A. Data analysis and interpretation: R.L.H., P.N.A. Manuscript first draft: R.L.H., P.N.A. Critical revisions of manuscript for important intellectual content: R.L.H., M.M.T., K.W.W., A.R.B., B.M., P.N.A. Approval of final draft: R.L.H., P.N.A.

Funding

This research was supported by a National Sciences and Engineering Research Council Discovery Grant and Canadian Research Chair in Cerebrovascular Physiology (P.N.A.).

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Dr Glen Foster for aiding in the optimal functioning of the end‐tidal forcing system and technical support.

This is an Editor's Choice article from the 15 June 2016 issue.

References

- Adelstein R & Conti M (1978). Phosphorylation of smooth muscle myosin catalytic subunit of adenosine 3′: 5′‐monophosphate‐dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem 253, 8347–8350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainslie PN & Duffin J (2009). Integration of cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity and chemoreflex control of breathing: mechanisms of regulation, measurement, and interpretation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 296, R1473–R1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainslie PN & Hoiland RL (2014). Transcranial Doppler ultrasound: valid, invalid, or both? J Appl Physiol 117, 1081–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bain AR, Smith KJ, Lewis NC, Foster GE, Wildfong KW, Willie CK, Hartley GL, Cheung SS & Ainslie PN (2013). Regional changes in brain blood flow during severe passive hyperthermia: effects of and extracranial blood flow. J Appl Physiol 115, 653–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brothers RM, Lucas RAI, Zhu YS, Crandall CG & Zhang R (2014). Cerebral vasomotor reactivity: steady‐state versus transient changes in carbon dioxide tension. Exp Physiol 99, 1499–1510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruhn H, Fransson P & Frahm J (2001). Modulation of cerebral blood oxygenation by indomethacin: MRI at rest and functional brain activation. J Magn Reson Imaging 13, 325–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busija D & Heistad D (1983). Effects of indomethacin on cerebral blood flow during hypercapnia in cats. Am J Physiol 244, H519–H524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemtob S, Beharry K, Barna T, Varma DR & Aranda J V (1991). Differences in the effects in the newborn piglet of various nonsteroidal antiinfla mmatory drugs on cerebral blood flow but not on cerebrovascular prostaglandins. Pediatr Res 30, 106–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coverdale NS, Gati JS, Opalevych O, Perrotta A & Shoemaker JK (2014). Cerebral blood flow velocity underestimates cerebral blood flow during modest hypercapnia and hypocapnia. J Appl Physiol 117, 1090–1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coverdale NS, Lalande S, Perrotta A & Shoemaker JK (2015). Hetergeneous patterns of vasoreactivity in the middle cerebral and internal carotid arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 308, H1030–H1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis RJ, Murdoch CE, Ali M, Purbrick S, Ravid R, Baxter GS, Tilford N, Sheldrick RLG, Clark KL & Coleman RA (2004). EP4 prostanoid receptor‐mediated vasodilatation of human middle cerebral arteries. Br J Pharmacol 141, 580–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson S, Hagenfeldt L, Law D, Patrono C, Pinca E & Wennmalm A (1983). Effect of prostaglandin synthesis inhibitors on basal and carbon dioxide stimulated cerebral blood flow in man. Acta Physiol Scand 117, 203–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan JL, Burgess KR, Thomas KN, Peebles KC, Lucas SJE, Lucas RAI, Cotter JD & Ainslie PN (2010). Influence of indomethacin on ventilatory and cerebrovascular responsiveness to CO2 and breathing stability: the influence of PCO2 gradients. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 298, R1648–R1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fog M (1939). Cerebral circulation: II. Reaction of pial arteries to increase in blood pressure. Arch Neurol Psychiatry 41, 260–268. [Google Scholar]

- Giller CA, Bowman G, Dyer H, Mootz L & Krippner W (1993). Cerebral arterial diameters during changes in blood pressure and carbon dioxide during craniotomy. Neurosurgery 32, 732–737. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goueli SA & Ahmed K (1980). Indomethacin and inhibition of protein kinase reactions. Nature 287, 171–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green DJ, Jones H, Thijssen D, Cable NT & Atkinson G (2011). Flow‐mediated dilation and cardiovascular event prediction: does nitric oxide matter? Hypertension 57, 363–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green RS, Leffler CW, Busija DW, Fletcher AM & Beasley DG (1987). Indomethacin does not alter the circulating catecholamine response to asphyxia in the neonatal piglet. Pediatr Res 21, 534–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heistad DD, Marcus ML & Abboud FM (1978). Role of large arteries in regulation of cerebral blood flow in dogs. J Clin Invest 62, 761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoiland RL, Ainslie PN, Wildfong KW, Smith KJ, Bain AR, Willie CK, Foster G, Monteleone B & Day TA (2015). Indomethacin‐induced impairment of regional cerebrovascular reactivity: implications for respiratory control. J Physiol 593, 1291–1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoiland RL, Day TA, Wildfong KW, Smith KJ, Bain AR, Willie CK, Foster GE, Monteleone B & Ainslie PN (2014). Hypercapnia induces dilation of large cerebral arteries and is mediated via a non‐selective cyclooxygenase pathway (LB704). FASEB J 28, suppl. LB704. [Google Scholar]

- Ide K, Eliasziw M & Poulin MJ (2003). Relationship between middle cerebral artery blood velocity and end‐tidal PCO2 in the hypocapnic–hypercapnic range in humans. J Appl Physiol 95, 129–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ide K, Worthley M, Anderson T & Poulin MJ (2007). Effects of the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor l‐NMMA on cerebrovascular and cardiovascular responses to hypoxia and hypercapnia in humans. J Physiol 584, 321–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inaba Y, Chen JA & Bergmann SR (2010). Prediction of future cardiovascular outcomes by flow‐mediated vasodilatation of brachial artery: a meta‐analysis. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 26, 631–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jallad NS, Garg DC, Martinez JJ, Mroszczak EJ & Weidler DJ (1990). Pharmacokinetics of single‐dose oral and intramuscular ketorolac tromethamine in the young and elderly. J Clin Pharmacol 30, 76–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]