Abstract

Objectives

The efficiency of a gatekeeping system for a health system, as in Germany, remains unclear particularly as access to specialist ambulatory care is not restricted. The aim was to compare the costs of coordinated versus uncoordinated patients (UP) in ambulatory care; with additional subgroup analysis of patients with mental disorders.

Design

Retrospective routine data analysis of patients with statutory health insurance, using claims data held by the Bavarian Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians. A patient was defined as uncoordinated if he or she visited at least 1 specialist without a referral from a general practitioner within a quarter. Outcomes were compared with propensity score matching analysis.

Participants

The study encompassed all statutorily insured patients in Bavaria contacting at least 1 ambulatory specialist in the first quarter of 2011 (n=3 616 510).

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Primary outcome was total costs of ambulatory care; secondary outcomes were financial claims of general physicians, specialists and for medication.

Results

The average age was 55.3 years for coordinated patients (CP, n=1 629 302), 48.3 years for UP (n=1 825 840). CP more frequently had chronic diseases (85.4%) as compared with UP (67.5%). The total unadjusted financial claim per patient was higher for UP (€234.52) than for CP (€224.41); the total adjusted difference was −€9.65 (95% CI −11.64 to −7.67), indicating lower costs for CP. The cost differences increased with increasing age. Total adjusted difference per patient with mental diseases as documented with an International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 F-diagnosis, was −€20.31 (95% CI −26.43 to −14.46).

Conclusions

Coordination of care is associated with lower ambulatory healthcare expenditures and is of particular importance for patients who are more vulnerable to medical interventions, especially for elderly and patients with mental disorders. The role of general practitioners as coordinators should be strengthened to improve care for these patients as this could also help to frame a more efficient health system.

Keywords: access to care, health spending, PRIMARY CARE, organization and delivery of care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive evaluation of healthcare expenditures of ambulatory coordinated care within a healthcare system with free access to primary and specialty care.

The present evaluation is based on routinely collected data which reveal valuable information from the ‘real-world’ of primary care.

A further strength is the large ambulatory data from Bavaria, containing patients from all statutory health insurances.

The study is limited by the absence of direct outcome indicators for the quality of healthcare.

A further limitation is the possibility of residual confounding due to unobserved variables within the propensity score matching procedure.

Introduction

Medical progress and demographic change are leading to increasing healthcare costs in the industrialised countries. It is a challenge to provide optimal medical care that need to be concerned with the expenditures of the welfare state. Good organisation of care is considered an important element to achieve well-balanced healthcare, and investments can be related to better health outcomes. Hence, there is an increasing engagement with healthcare reforms, such as the Affordable Care Act in the USA. Several studies have shown that good organisation of primary care is a hallmark for lower costs and better health outcomes.1–3 This effect is attributed in part to the coordination of care by general physicians (GPs).1 Coordination of care is best realised in gatekeeping systems;4 hence, even countries like Germany with direct access to specialist care are increasingly introducing gatekeeping elements to strengthen primary care.5

The German healthcare system strongly demarcates between ambulatory care and hospital care. Within ambulatory care, GPs and medical specialists, who all work in licensed private practices, are directly accessible to patients.5 GPs account for 43% of all ambulatory care physicians. Approximately 90% of German inhabitants are covered by compulsory statutory health insurance. Statutory health insurance funds pay a fixed amount to the regional Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians, which then remunerates physicians based on a system that combines capitation with fee for service. Approximately 10% of patients are privately insured, mostly civil servants and people with an income higher than €49 950 per year. Privately insured patients pay out of their pocket, and claim their expenses back from the private insurance company. Statutory insured patients can choose their doctor, who might be a GP or a specialist, every 3 months. Concerning coordination of care, Germany has a weak primary care system.6 Between 2004 and 2012, a co-payment of €10 was charged for the first ambulatory visit in each 3-month period, regardless of whether a GP or an ambulatory specialist was being consulted. If the patient consulted a different practice in the same quarter, the fee was waived only on referral from another ambulatory physician, who could be a GP or specialist. Thus, providing that further practices were consulted only on referral, payment was solely required once per quarter. However, this provided no guarantee of GP-led gatekeeping. The primary aim was to reduce the number of physician visits5 because Germany has very high contact rates,7 an average of 18 practice contacts per year, which increase particularly for patients with mental disorders.8 These patients often make more extensive use of health services, leading to misallocation of expenditure when this usage is inappropriate. It is beyond doubt that unnecessary or repeated diagnostic tests can harm the patient, for example, when surgical procedures or high radiation exposures are involved. A further aim of the co-payment was to strengthen the position of the GP as a coordinator of care. The co-payment was withdrawn at the end of 2012 because the impact on the number of physician visits was deemed to be negligible.5

The aim was to compare the costs of coordinated versus uncoordinated outpatients care with a retrospective routine data analysis of the Bavarian Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians (Kassenärztliche Vereinigung Bayerns, KVB). An additional subgroup analysis considered patients with mental disorders to evaluate the impact of coordination within this important collective group due to the high risk of their inappropriate or repeated usage of health services.8

Methods

Sources of data

The KVB processes claims data for all statutorily licensed ambulatory physicians in Bavaria, Germany. This includes ∼9000 GPs, 13 000 specialists and 4000 psychotherapists (including both psychological and medical psychotherapists) who provide ambulatory care for the 12 million inhabitants of Bavaria and bordering areas of Germany. Specialists in ambulatory care comprise anaesthesiologists, dermatologists, ENT specialists, gynaecologists, internists with and without specialisation (eg, cardiology, gastroenterology, pneumology and oncology), neurologists, ophthalmologists, orthopaedists, psychiatrists, psychotherapists, radiologists, surgeons and urologists. Some internists without specialisation are licensed as family physicians and are, therefore, included in the group of family physicians. Both specialists and family physicians receive a set fee, depending on age, for each patient treated in a given quarter (‘contact capitation’). Certain time-consuming or technical services, such as chronic disease management, lung function testing, emergency visits or ultrasound, are claimed in addition to the basic fee. The catalogue of fees for medical services of the specialists comprises a wide range of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures; for example, for MRI, surgical procedures and even intracardiac catheters. The fee-for-service claims account for between 60% and 100% of all claims among specialists and ∼40% of claims among family physicians.

The patient data, which are mandatorily documented for claims purposes, comprise diagnoses and coded information about diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. All costs are given in Euros and represent the amount claimed by the physician. Furthermore, referral data records both the referrer and the consulting physician. In addition to these claims data, the KVB holds patient-level prescribing data detailing both the substance prescribed and their cost in Euros.

Study design

The evaluation was performed as a retrospective routine data analysis. A patient was defined as coordinated if every specialist consultation within a quarter was conducted by referral from a GP. Vice versa, a patient was defined as uncoordinated if he or she visited at least one specialist within a quarter without a referral from a GP. In order to prevent distortion due to, for example, specialists billing for emergency treatment or routine screening (eg, mammography), only regular physician contacts were considered when determining the coordination status. The first quarter of 2011 was used as reference quarter since the co-payment of €10 was still applied to foster coordinated care. The calculation of the differences was repeated for the other three-quarters of 2011 to validate our findings by replication. Inclusion criteria were a minimum age of 18 years to avoid confusion with the workload of paediatricians, and the existence at least of one regular specialist visit within a quarter. The study was performed in accordance with the main German guideline ‘Good Practice for Secondary Data Analysis’ (Gute Praxis Sekundärdaten, GPS). The data were anonymous. Approval was obtained from the responsible data protection officer.

Statistical analysis

We assumed that the coordination of care has a causal effect on the financial claims made by GPs and specialists, and on the cost of medication. However, we also suspect that the groups of patients with and without coordination differ substantially with respect to demographic characteristics and morbidity. We, therefore, used the propensity score matching (PSM) methodology of Rosenbaum and Rubin9 to allow for targeted inferences regarding the effect of the coordination of care.10 Our chosen methodology used caliper matching on the propensity score without replacement to create a balanced data set before the effect of interest was estimated using standard linear regression models.11 12 Bias was assessed by calculating the standardised absolute difference, whereby differences of 10% or less may be considered small.13 14 The R package ‘Matching’ was used to facilitate the matching, without replacement, of each member of the treatment groups with one member of the pools of potential controls.

The following variables were used for PSM: sex, age, morbidity, participation in disease management programmes (DMPs), rural versus urban area, regional deprivation and encountered specialists. Morbidity was measured using the diagnoses documented by the specialists using the German modification of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 system. To ensure a comparison of the two groups based on equal information, any diagnoses documented by GPs were ignored. We assume that the diagnosis entered by the specialist provides an unbiased account of the patient's morbidity before treatment. Diagnoses were aggregated using the H15EBA grouper, which was developed to measure morbidity within the German ambulatory system. The grouper specifies 60 different medical condition categories. The ‘Institut des Bewertungsausschusses’ (InBA; Institute for Strategic Assessment of Reimbursement for Medical Services), an official organ of the German Ministry of Health, developed a German grouper that maps ICD-10 diagnoses to the condition categories.15 The principles of this grouper were based on the final report for the US Health Care Financing Administration ‘Diagnostic Cost Group Hierarchical Condition Category Models for Medicare Risk Adjustment’;16 and were adapted for the German healthcare system. The use of such groups, designed to predict the cost of treatment, enables the complex ICD diagnoses data to be summarised for analysis in a meaningful manner. Participation in a DMP for diabetes, coronary artery disease, asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was used as a further measure of morbidity. As the DMP seek to improve the GP-led coordination of care, DMP participation may also be a predictor of coordination.

The Bavarian Index of Multiple Deprivation (BIMD) was used to account for regional effects of deprivation on health. The BIMD was developed as a small-area, multidimensional deprivation index for Bavaria, and is based on an established British method.17 It was created with official sociodemographic, socioeconomic and environmental data. A correlation analysis using this index showed a stepwise increase of mortality risk with increasing regional deprivation; and communities in the highest deprivation quintile showed a clearly higher mortality risk, both for total and for premature mortality.17 Another study from Bavaria showed that increased lung cancer risk in men and colorectal cancer risk for both genders were significantly associated with increasing BIMD.18

The main outcome variable was the total cost of ambulatory care, while secondary outcome variables were financial claims of GPs, specialists and medication costs. A secondary analysis was performed for patients with mental disorders as defined by the relevant diagnosis groups (ie, TCC055, TCC057, TCC058, TCC060, RCC011 or RCC012). This largely corresponds to the documentation of an ICD-10 F-Code, but excludes dementia and includes self-harm (X84) and burnout (generally coded as Z72).

Results

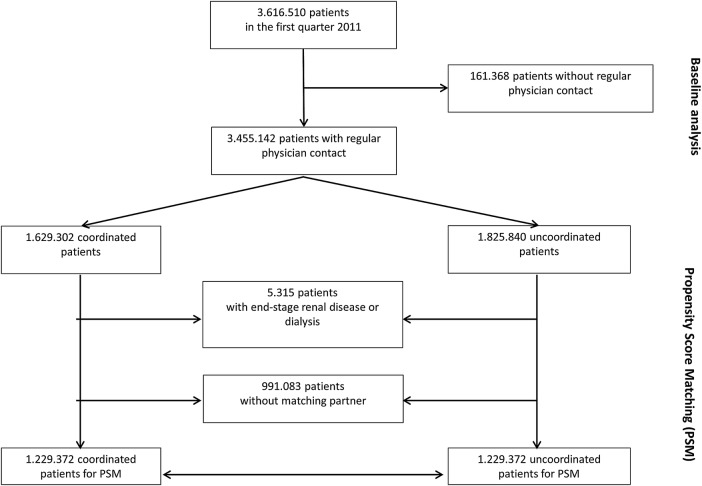

The complete data set from 2011 included data of 8 607 191 patients who had contact with a specialist practice with or without referral. In total, 3 616 510 patients encountered the specialists within the first quarter of 2011 (figure 1). The coordination of care could not be determined for 161 368 (4.5%) patients as they had contact with specialists outside the context of regular care (eg, emergency out-of-hours treatment or mammography screening programme). These patients were younger than the coordinated patients (CP), more often female, and had lower claims and prescribing costs. A total of 3 455 142 patients were potentially eligible for the PSM.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of analysed patients.

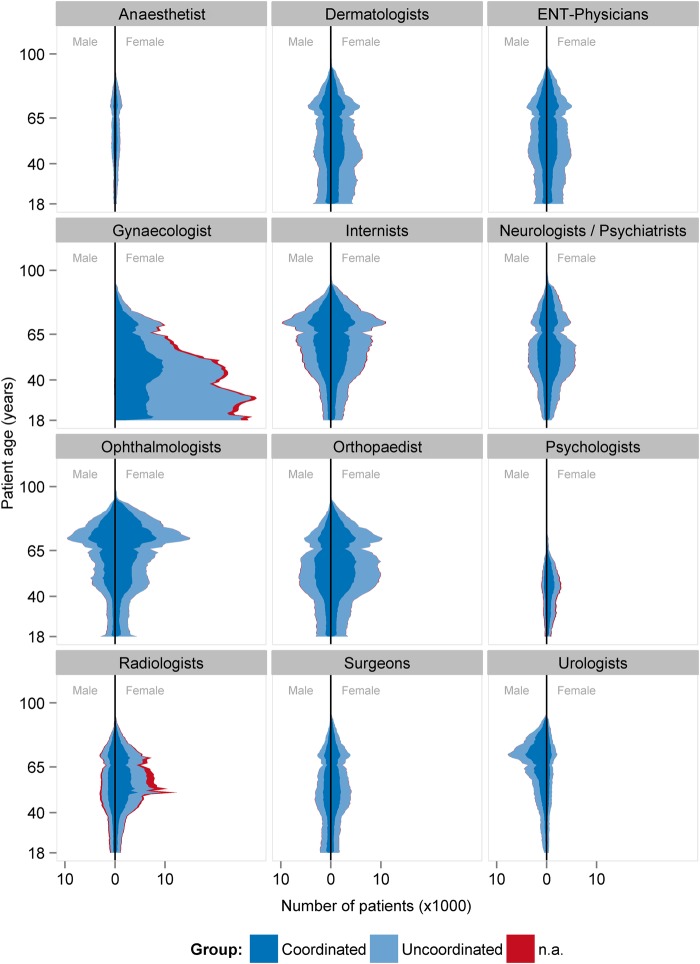

Of these patients, 50.5% had contacted at least one specialist without referral (table 1). Uncoordinated patients (UP) were younger, had less chronic diseases and a higher proportion of mental diseases than CP. UP visited more often multiple specialists of the same discipline (doctor shopping) than CP, had higher contact rates with specialists and visited more different physician groups. The average claims for the specialists, and the total financial claim per patient were higher in UP than in CP. The calculation of differences relating to the other three-quarters of 2011 showed similar results (see online supplementary appendix table 1). Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of the patients’ age and sex for each specialist group for the first quarter of 2011.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients

| First quarter of 2011 | Coordinated care | Uncoordinated care | Coordination not determinable |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | 1 629 302 (45.1) | 1 825 840 (50.5) | 161 368 (4.5) |

| Age (mean) | 55.3 | 48.3 | 49.0 |

| Gender: male (%) | 614 274 (37.7) | 606 793 (33.2) | 47 390 (29.4) |

| Proportion of chronic disease (%) | 85.4 | 67.5 | 51.4 |

| Number of medical condition categories (mean) | 3.6 | 4.02 | 1.5 |

| Proportion of doctor shopping (%) | 1.3 | 8.9 | 0.1 |

| Proportion of mental diseases categories (%) | 16.8 | 18.3 | 12.1 |

| Number of different physicians (mean) | 1.9 | 2.2 | 1.3 |

| Number of different physician groups (mean) | 1.6 | 1.8 | 1.1 |

| Proportion with different specialists (%) | 42.2 | 45.7 | 8.5 |

| GP financial claim in € (Σ) | 109 336 976 | 87 597 417 | 6 459 389 |

| SP financial claim in € (Σ) | 256 292 907 | 340 590 071 | 15 391 547 |

| Total financial claim in € (Σ) | 365 629 883 | 428 187 488 | 21 850 936 |

| GP financial claim/patient in € (mean) | 73.10 | 73.59 | 75.15 |

| SP financial claim/patient in € (mean) | 157.30 | 186.54 | 95.38 |

| Total financial claim/patient in € (mean) | 224.41 | 234.52 | 135.41 |

| Proportion of patients without GP financial claim (%) | 8.2 | 34.8 | 46.7 |

| Proportion of patients with €1–40 GP financial claim (%) | 22.6 | 18.7 | 15.9 |

| Total drug prescription costs/patient in € (mean) | 158.94 | 146.36 | 84.17 |

| SP drug prescription costs/patient in € (mean) | 74.81 | 89.66 | 31.18 |

| Number of drug prescriptions/patient (mean) | 3.30 | 2.73 | 1.76 |

| Number of SP drug prescriptions/patient (mean) | 0.8 | 1.1 | 0.3 |

| Total DDD/patient (mean) | 182.7 | 140.2 | 91.8 |

| SP DDD/patient (mean) | 33.0 | 48.1 | 13.6 |

DDD, defined daily dose; GP, general physician; SP, specialist.

Figure 2.

Patients’ age and sex distribution related to the specialists. N.a, not applicable.

bmjopen-2016-011621supp_tables.pdf (271.7KB, pdf)

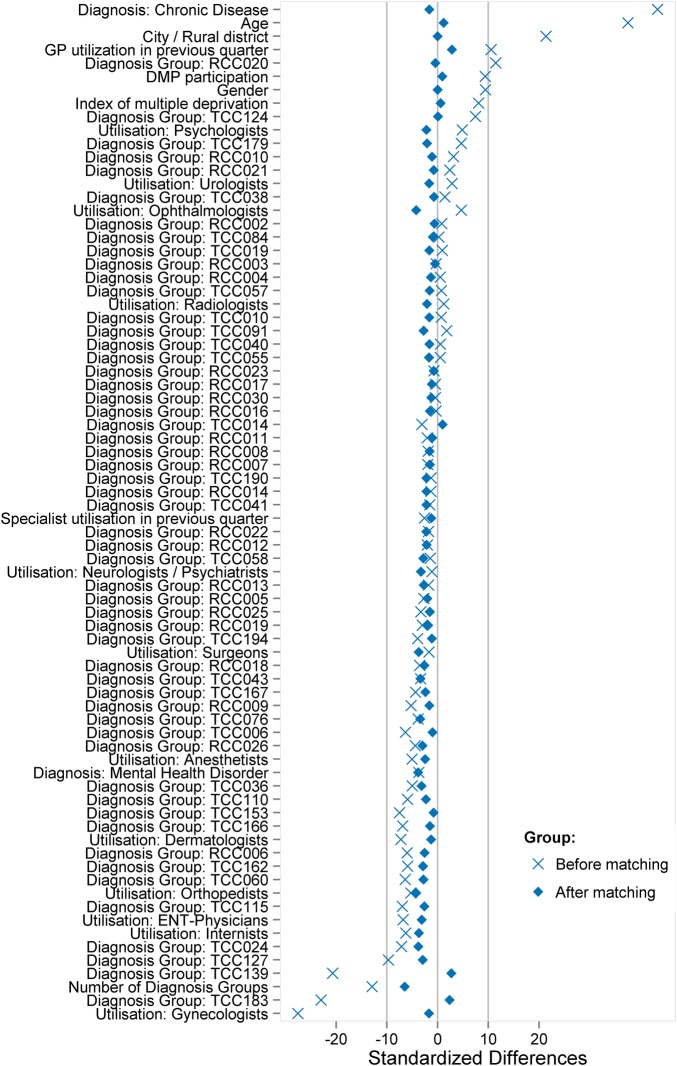

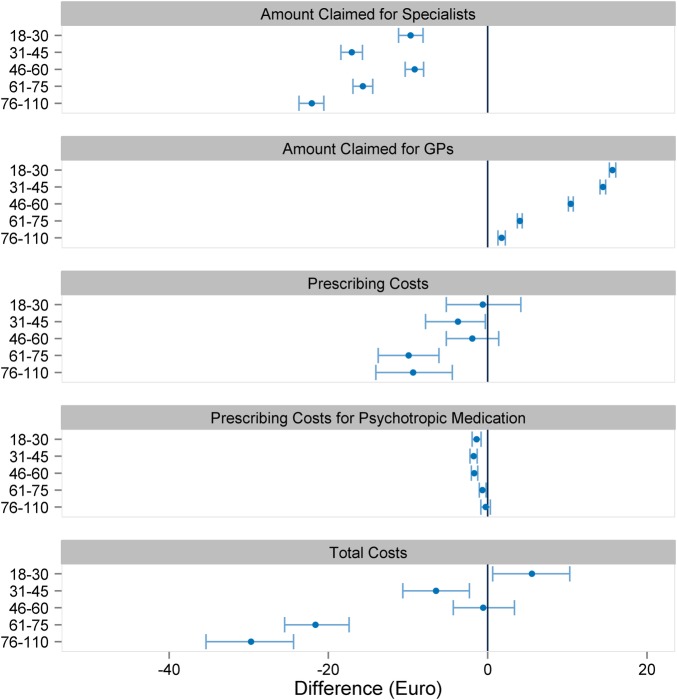

A total of 2 458 744 patients were taken into account for PSM. Altogether, 74 variables were used for PSM (figure 3). There was no meaningful change in sex and age distribution after matching. No matching partner was found for 991 083 patients. These patients were predominantly female and younger than 50 years, and allocated to the risk class TCC183 (contraception, vaccination, gynaecological prevention check-up) and/or TCC139 (menstrual disorder, menopause), and therefore assigned to the gynaecologists (figure 2). A further 5315 patients with end-stage renal diseases (TCC129) and renal dialysis (TCC130) were not considered for PSM. Patients with severe renal diseases are often under the coordination of nephrologists, and the high costs could lead to an unwarranted exaggeration of the treatment effect in favour of the CP group. Before matching, the CP group exhibited higher levels for the presence of a chronic disease, age, residence in a rural area and GP contact in the previous quarter. After matching, the standardised difference of each matching variable was reduced to below 10%, suggesting an acceptable level of bias reduction (figure 3). The regression analysis results related to the total costs are displayed in figure 4 (detailed results in online supplementary appendix table 2). The financial claims of the specialists were generally higher for UP, irrespective of the patients' age. When the financial claims of GPs and specialists are combined (total costs), care for UP between the ages of 18 and 30 years was less costly. With increasing age, however, the lower total cost of the CP group becomes increasingly pronounced. Averaging over age, the total difference per patient was −€9.65 (95% CI −11.64 to −7.67) in favour of coordinated care.

Figure 3.

Propensity score matching—absolute standardised differences before and after matching and comparing different covariates for coordinated and uncoordinated patients. GP, general practitioner; DMP, disease management programme; ENT, ear, nose and throat.

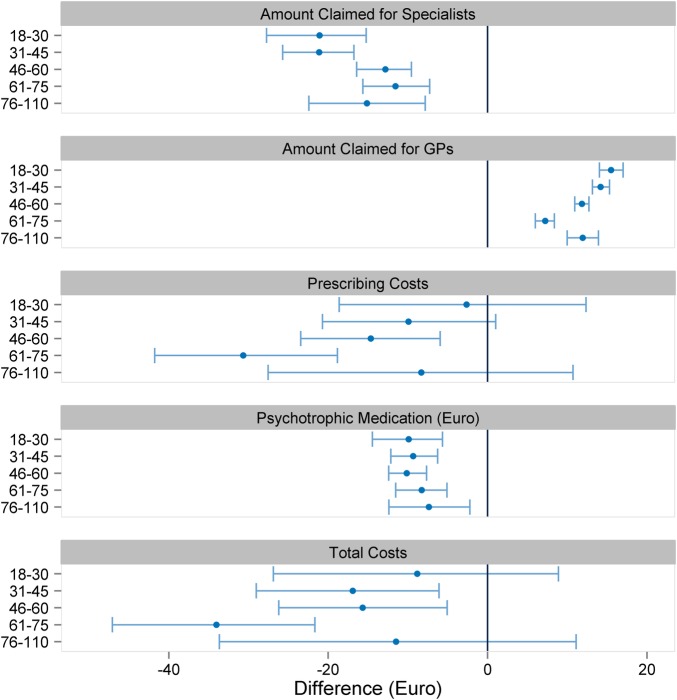

Figure 4.

Comparison of coordinated and uncoordinated patients. Values are mean (95% confidence interval). GP, general practitioner.

The impact of coordination of care for patients with mental disorders was calculated using 267 520 patients with a recorded mental disorder, of whom 130 526 (48.8%) received coordinated care (figure 5). There was a similar trend with respect to increasing cost differences with increasing age in favour of coordinated care. The prescription of psychotropic medication, measured in terms of cost, was higher in the uncoordinated group (detailed results in online supplementary appendix table 3). Averaging over age, the total difference per patient was −€20.31 (95% CI −26.43 to −14.46) in favour of coordinated care for these patients.

Figure 5.

Comparison of coordinated and uncoordinated patients with mental disorders. Values are mean (95% confidence interval). GP, general practitioner.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to evaluate the healthcare expenditures of ambulatory coordinated care within a healthcare system with free access to primary and specialty care, independent of health insurance funds in Germany and encompassing almost all medical specialists in ambulatory care. Cost of care for coordinated patients was less costly than that for uncoordinated patients. The impact of coordination of care on healthcare resources increased with age. Patients with mental disorders are prone to uncoordinated care, which is accompanied by increased prescription of psychotropic medication.

The advantages of coordinated care have already been described by Starfield et al.3 However, their review was carried out without the possibility to include German routine data for cost analysis. Our findings may close this knowledge gap, illustrating an important impact of coordination for costs of care within a health system with free choice of specialist ambulatory care. Our findings seem to be partly inconsistent with those of a recent ecological study investigating the correlation of costs and primary care orientation among several European countries, including Germany.19 The authors reported that overall health expenditures were higher in countries with stronger primary care structures. Yet, ecological studies are prone to multiple biases. We believe that at least for Germany, our data based on individual patient data are stronger.

Besides the issue of costs, coordination of care should also be viewed as an important contribution to the health of the population.3 20 This might be of importance due to the different organisational levels of different healthcare systems. Within modern health systems, gatekeepers as coordinators are positioned between organisations and individuals who wish to use resources within those organisations.4 However, the impact on patient satisfaction is ambiguous. It was shown that patients evaluate their GPs more positively when they have free access to healthcare services, including specialty care,21 which was the case in Germany. It needs critical reflection whether completely liberal supply of medical service is really helpful for the patients. It was shown in a representative US sample that higher patient satisfaction was associated with less emergency department use but with greater inpatient use, higher overall healthcare and prescription drug expenditures, and increased mortality.22 It is advocated that good coordination of care by a GP protects from oversupply of medicine, which might be accompanied by medical errors and false medication.23 Along with this, the impact of coordination of care in our sample is particularly strong for elderly patients. This might illustrate that GPs are most important when patients are ageing and becoming, therefore, more vulnerable to multimorbidity and the associated complexity in diagnosis and therapy. Thus, our results demonstrate the reality of the recently developed participatory model of the paradox of primary care.24 Our results, however, differ from the effects of specific general practitioner-centred healthcare models.25–27 The evaluation of these models showed an increase in GP and specialist contacts when patients were enrolled. However, selection mechanisms of patients with higher morbidity, recall bias in interview surveys, or changes in patients' or physicians' behaviour might complicate the interpretation of such effects. The naturalistic observation without intervention (with exception for €10 practice fee) might be an advantage for our study related to these aspects.

Our findings also highlight the importance of GPs for patients with impaired mental health. Good coordination of care is valuable for them as high usage is associated with harmful side effects.28 29 We found strong indications of ‘doctor shopping’ with multiple consultations, even among practices with the same medical specialisation, when these patients are uncoordinated. This also becomes apparent in the light of the increased prescription rate of psychotropic medication for these patients. It is still a challenge to provide optimal care for these patients within a system with free access to all kinds of specialty care. Nevertheless, our results might indicate that patients mostly benefit from coordinated care in the German health system. Yet it must be considered that this effect could not only be due to gatekeeping, but might rather be underpinned by the primary care physicians' diagnostic and therapeutic interventions, and the using of own problem-solving strategies according to the concept of comprehensive and long-term focused care.3 20 24 This hypothesis is, however, purely speculative.

At this point, it should be noted that our findings are based solely on routine data and cost analyses. The costs can only serve as a surrogate for turnover in patient care, but not as a direct outcome indicator for the quality of healthcare. The cost evaluation might serve as an indication of the impact of uncoordinated care on high healthcare usage, with all its consequences with respect to medication errors and harmful investigations. However, an important limitation is that it is not possible to draw a conclusion about the medical outcomes as we had no access to mortality or hospitalisation data. A further limitation is that we could not investigate the impact of multiple uncoordinated GP visits. However, this might rather lead to an underestimation of the effects of coordinated care. The limitation of the PSM in itself needs to be kept in mind, which always bears the risk of unidentified confounding variables. However, we were able to control the most important variables, such as morbidity and regional deprivation, thus matching the patients with respect to 74 variables. We could not assign 991 083 patients for matching. They were predominantly female and younger than 50 years. In Germany, gynaecologists are often consulted by younger female patients for routine care (eg, contraception and sexual health) in place of a general practitioner (see also figure 2). These patients are rather healthy and generate comparatively lower healthcare costs. Therefore, while we can make no inference for these patients, it seems unlikely that our results are distorted by this effect. Beyond this, the reproducibility of the cost differences for the other quarters might underline the robustness of our analysis.

To conclude, our results contribute to an understanding of the impact of coordinated care in a health system with free access to primary and specialty care. Coordination of care was particularly of importance for the elderly and for patients with mental disorders. These patients are more vulnerable to medical interventions. Therefore, the role of the family physicians as coordinators should be strengthened to improve care, which could also help in the framing of a more efficient health system.

Footnotes

Contributors: AS, ED, MT, RG, WM, AM, KL, and MM designed the study. ED performed the analysis. AS and MM wrote the initial version of the manuscript. ED, MT, RG, WM, AM, and KL revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The study was funded by the Central Research Institute for Ambulatory Health Care in Germany (Zentralinstitut für die Kassenärztliche Versorgung in Deutschland).

Competing interests: ED, MT and RG are employees of the Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians of Bavaria.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Macinko J, Starfield B, Shi L. Quantifying the health benefits of primary care physician supply in the United States. Int J Health Serv 2007;37:111–26. doi:10.2190/3431-G6T7-37M8-P224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Starfield B. Is primary care essential? Lancet 1994;344:1129–33. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(94)90634-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q 2005;83:457–502. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forrest CB. Primary care in the United States: primary care gatekeeping and referrals: effective filter or failed experiment? BMJ 2003;326:692–5. doi:10.1136/bmj.326.7391.692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Groenewegen PP, Dourgnon P, Greß S et al. . Strengthening weak primary care systems: steps towards stronger primary care in selected Western and Eastern European countries. Health Policy 2013;113:170–9. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.05.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kringos D, Boerma W, Bourgueil Y et al. . The strength of primary care in Europe: an international comparative study. Br J Gen Pract 2013;63:e742–50. doi:10.3399/bjgp13X674422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koch K, Miksch A, Schürmann C et al. . The German health care system in international comparison: the primary care physicians’ perspective. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2011;108:255–61. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2011.0255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schneider A, Hilbert B, Hörlein E et al. . The effect of mental comorbidity on service delivery planning in primary care: an analysis with particular reference to patients who request referral without prior assessment. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2013;110:653–9. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2013.0653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrica 1983;70:41–55. doi:10.1093/biomet/70.1.41 [Google Scholar]

- 10.D'Agostino RB., Jr Propensity score methods for bias reduction in the comparison of a treatment to a non-randomized control group. Stat Med 1998;17:2265–81. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19981015)17:19<2265::AID-SIM918>3.0.CO;2-B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gelman A, Hill J. Data analysis using regression and multilevel/hierarchical models. 1st edn Cambridge: University Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ho DE, Imai K, King G et al. . Matching as nonparametric preprocessing for reducing model dependence in parametric causal inference. Political Anal 2007;(15):199–236. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Austin PC. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat Med 2009;28:3083–107. doi:10.1002/sim.3697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd edn Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Institut des Bewertungsausschusses. Bericht zur Schätzung der Morbiditätsveränderung 2008/2009 und zur Repräsentativität und Plausbilität der Datengrundlage des Bewertungsausschusses 2009. http://institut-bade/publikationen/Bericht_SchaetzungMorbiditaetsveraenderungpdf

- 16.Pope GC, Ellis RP, Ash AS et al. . Diagnostic cost group hierarchical condition category models for Medicare risk adjustment—final report. http://wwwcmshhsgov/Reports/downloads/pope_2000_2pdf 2000.

- 17.Maier W, Fairburn J, Mielck A. Regional deprivation and mortality in Bavaria. Development of a community-based index of multiple deprivation. Gesundheitswesen 2012;74:416–25. doi:1010.1055/s-0031-1280846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuznetsov L, Maier W, Hunger M et al. . Regional deprivation in Bavaria, Germany: linking a new deprivation score with registry data for lung and colorectal cancer. Int J Public Health 2012;57:827–35. doi:10.1007/s00038-012-0342-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kringos DS, Boerma W, van der Zee J et al. . Europe's strong primary care systems are linked to better population health but also to higher health spending. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013; 32:686–94. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stange KC, Ferrer RL. The paradox of primary care. Ann Fam Med 2009;7:293–9. doi:10.1370/afm.1023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kroneman MW, Maarse H, van der Zee J. Direct access in primary care and patient satisfaction: a European study. Health Policy 2006;76:72–9. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2005.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fenton JJ, Jerant AF, Bertakis KD et al. . The cost of satisfaction: a national study of patient satisfaction, health care utilization, expenditures, and mortality. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:405–11. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Starfield B. New paradigms for quality in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 2001;51:303–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Homa L, Rose J, Hovmand PS et al. . A participatory model of the paradox of primary care. Ann Fam Med 2015;13:456–65. doi:10.1370/afm.1841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schnitzer S, Balke K, Walter K et al. . Führt das Hausarztmodell zu mehr Gleichheit im Gesundheitssystem? Bundesgesundheitswesen 2011;54:942–50. doi:10.1007/s00103-011-1317-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Höhne A, Jedlitschka K, Hobler D et al. . General practitioner-centred health-care in Germany. The general practitioner as gatekeeper. Gesundheitswesen 2009;71:414–22. doi:1010.1055/s-0029-1202330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ose D, Broge B, Riens B et al. . Contacts to specialists with referrals by GP—have GP centred health care (HZV) contracts an impact? Z Allg Med 2008;84:321–6. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1083787 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fink P. Surgery and medical treatment in persistent somatizing patients. J Psychosom Res 1992;36:439–47. doi:10.1016/0022-3999(92)90004-L [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kouyanou K, Pither CE, Wessely S. Iatrogenic factors and chronic pain. Psychosom Med 1997;59:597–604. doi:10.1097/00006842-199711000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-011621supp_tables.pdf (271.7KB, pdf)