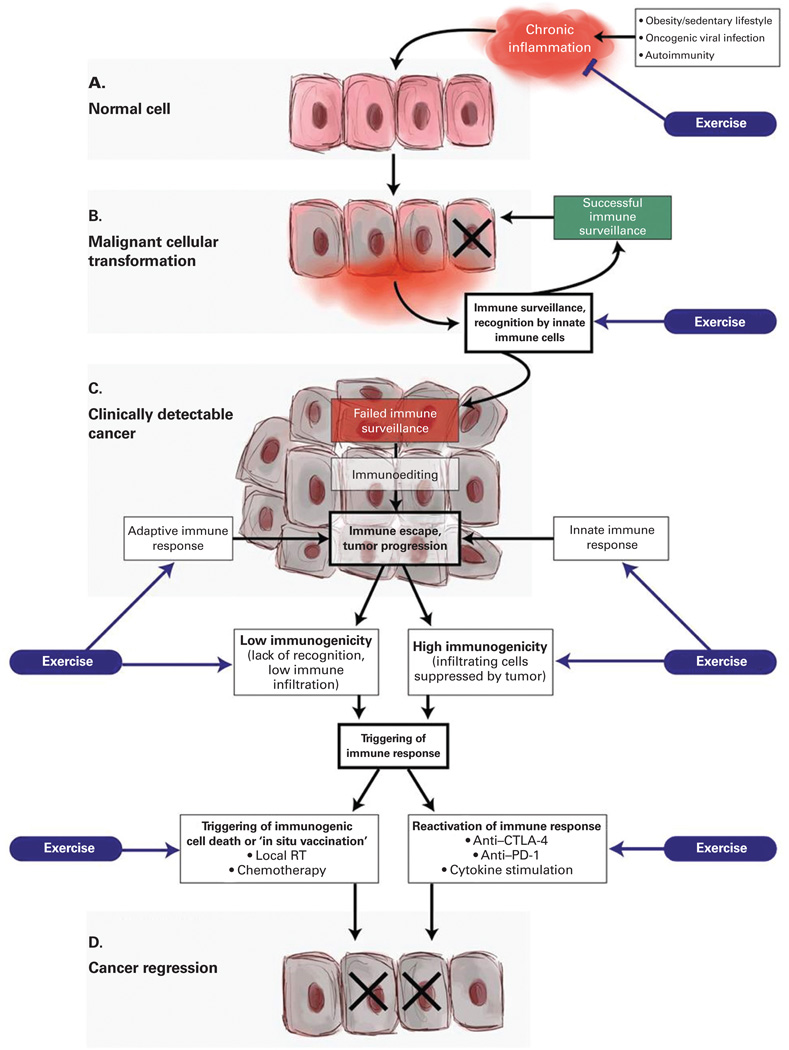

Figure 2. A conceptual framework to discern the potential role of exercise in regulating inflammation-immune axis function in cancer initiation and progression.

(A) Chronic inflammation can be initiated and maintained in patients suffering from a variety of conditions, including autoimmune reactions, persistent viral infections, and obesity (due to pro-inflammatory adipokine secretion). Sustained secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines can result in transformation of cells that can ultimately lead to cancer. There is emerging evidence that exercise can reduce a variety of markers of inflammation. (B) Most premalignant cells are eliminated by innate immune cells in a process of immune surveillance, particularly by NK cells that are specialized in eliminating cells infected by viruses or undergoing cellular transformation. It has been reported that exercise leads to increased numbers of circulating NK cells, as well as to potentiated NK cell cytotoxic function, although the evidence is inconclusive. (C) In cases where transformed cells are able to avoid elimination, they are instead kept in equilibrium with surrounding immune cells. Over long periods of time and sustained immunologic pressure, a Darwinistic microselection process takes place in which tumor cells that acquire additional mutations become resistant to killing by immune cells, surviving and making the emerging tumor decreasingly immunogenic. Ultimately, the tumor is able to escape from immune control, the growth rate accelerates, and the cancer becomes clinically detectable. Although minimal evidence exists, exercise may positively influence innate and adaptive immune responses following immune escape and subsequent tumor growth. (D) The occurrence and strength of spontaneous tumor-specific immune responses varies significantly depending on the tumor type and the affected individual. In tumors that have evidence of a pre-existing adaptive immune response (high immunogenicity), the infiltrating tumor-specific T cells can be reactivated by the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors (anti–CTLA-4, anti–PD-1), thus triggering a direct antitumor effect. In tumors that have low immunogenicity, there is a lack of recognition of tumor antigens, which renders the tumor invisible to T-cell attack. In order to generate an adaptive immune response in such tumors, a de novo antitumor immune response must be initiated. Localized tumor irradiation has been shown to trigger immunogenic cell death of tumor cells, resulting in release of tumor antigens and concomitant danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) that allow tumor-resident dendritic cells to become activated, engulf the exposed tumor antigens, and subsequently present the antigens to naive T cells to trigger tumor-specific immune responses. Minimal evidence suggests that dendritic cell number may increase with exercise; currently, no evidence exists for the role of exercise in triggering immunogenic cell death or reactivation of the immune system. CTLA-4 = cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen 4; NK cell = natural killer cell; PD-1 = programmed death 1; RT = radiation therapy.