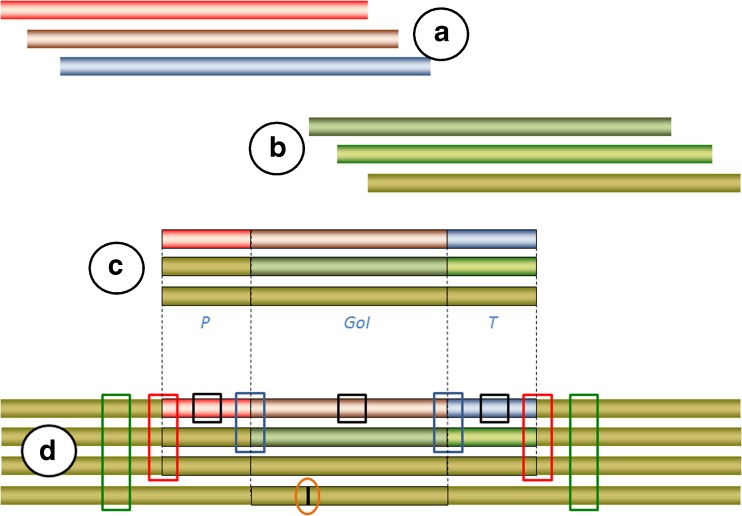

Fig. 1.

The relationships between genetic modifications and sequence motifs suitable for detection and identification of genetically modifies organisms (GMOs). A: Chromosomes of taxa distantly related to the genetically modified taxon (e.g., red for virus, brown for fungus, blue for bacterium). These are sources of transgenic sequence motifs. B: Chromosomes of the modified species or closely related, sexually compatible species (taxa; various tones of green). These are sources of intragenic and cisgenic sequence motifs. C: Genetic constructs (functional cassettes) as intended for insertion into the recipient organism, comprising (each element is framed) the promoter (P), gene of interest (trait gene; GoI), and terminator (T); top transgenic construct, middle intragenic construct (i.e., with elements combined into a nonnaturally occurring configuration), bottom cisgenic cassette (i.e., with original naturally occurring configuration). D: Genetic modification types as they appear in the recipient chromosomal locus: top transgenes, upper middle intragenes, lower middle cisgenes, bottom single nucleotide modification (vertical black bar). Four types of sequence motifs are commonly targeted for detection and identification of GMOs: screening elements (open black boxes; a single element of a construct), construct-specific junctions (open blue boxes; motif is a chimera of two different elements of the construct), event-specific junctions (open red boxes; motif is a chimera of the insert and the native insertion locus), and taxon-specific motifs (open green boxes; typically a single copy housekeeping gene serving as a reference gene for identification and quantification of the modified taxon). The number of alternative targets that can be used to detect GMOs decreases as one move from transgenes (event-, construct-, and element-specific motifs) via intragenes (event- and construct-specific motifs) to cisgenes (only event-specific motifs). This has a great impact on the approaches taken/required for GMO detection, and challenges the current paradigm of screening before identification and quantification. Single nucleotide modifications and naturally occurring single nucleotide polymorphisms are indistinguishable from each other (orange oval). Rearrangements of the inserted genetic construct and native genome are not uncommon (not shown)