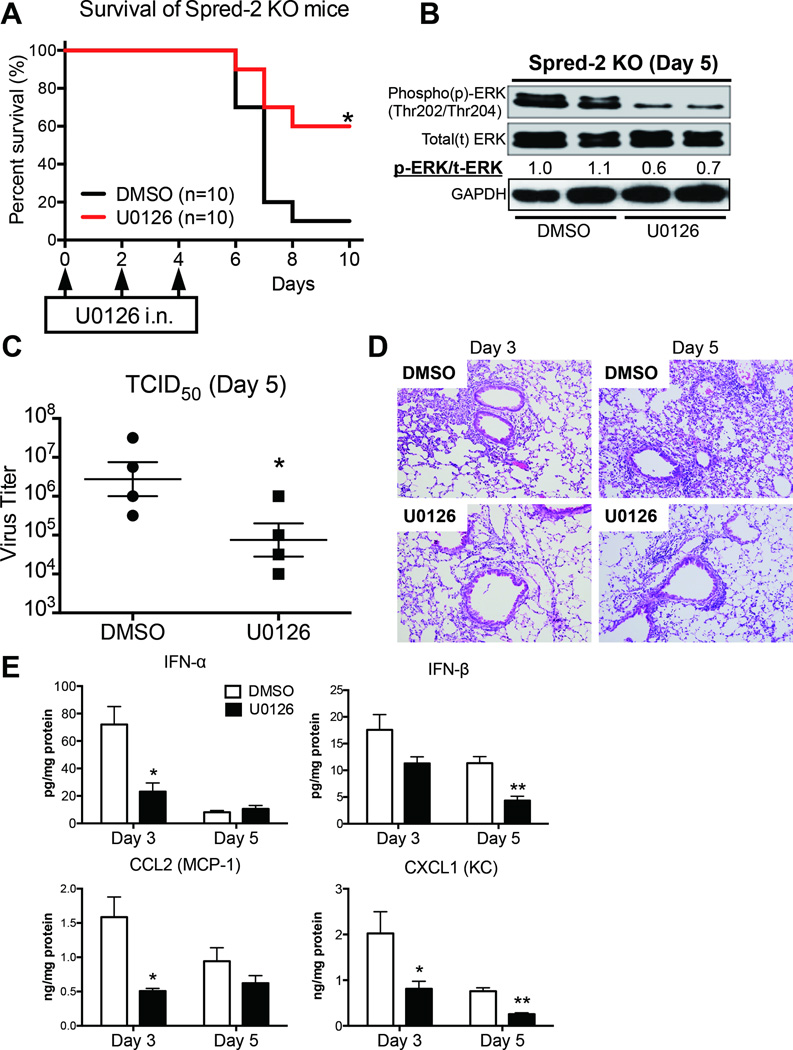

Figure 4. Blocking of MEK signaling improves survival rate, viral load, and lung inflammation.

U0126 (200 µg; 20 µl volume) was intranasally administrated to mice at days 0, 2 and 4 after influenza virus challenge. DMSO in 20 µl was used as a control for U0126. (A) Survival rate of Spred-2 KO mice treated with either control DMSO or U0126 after intranasal injection with 1 × 102 pfu H1N1. *p < 0.05 compared with WT mice. n=10 per group. (B) Lungs from Spred-2 KO mice treated with either control DMSO or U0126 after intranasal injection with 1 × 102 pfu H1N1 were harvested at day 5 after H1N1 challenge and extracts were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. Data are expressed from a representation of two independent experiments. A representative gel images and the value of phosphorylation compared with lung from DMSO-treated mice are shown. (C) Viral load in Spred-2 KO mice treated with control DMSO or U0126 at day 5 after influenza virus infection, measured by TCID50. *p < 0.05 compared with WT mice. Data shown indicate mean ± SEM and are from a representative experiment of 2 independent experiments. Each group had 5 mice per group. (D) Representative histological appearance of lungs isolated from Spred-2 KO mice treated with either control DMSO or U0126 after intranasal injection with 1 × 102 pfu H1N1, harvested at day 5 after H1N1 infection. H&E staining. Original magnification, ×40; ×200. (E) Protein level of cytokines and chemokines from whole lungs was measured by ELISA.*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 compared with WT mice. Data shown indicate mean ± SEM and are from a representative experiment of 3 independent experiments. Each group had 5 mice per group.