Abstract

The knee is frequently affected by severe orthopedic changes known as hemophilic arthropathy (HA) in patients with deficiency of coagulation factor VIII or IX and thus this manuscript seeks to present a current perspective of the role of the orthopedic surgeon in the management of these problems. Lifelong factor replacement therapy (FRT) is optimal to prevent HA, however adherence to this regerous treatment is challenging leading to breakthrough bleeding. In patients with chronic hemophilic synovitis, the prelude to HA, radiosynovectomy (RS) is the optimal to ameliorate bleeding. Surgery in people with hemophilia (PWH) is associated with a high risk of bleeding and infection, and must be performed with FRT. A coordinated effort including orthopedic surgeons, hematologists, physical medicine and rehabilitation physicians, physiotherapists and other team members is key to optimal outcomes. Ideally, orthopedic procedures should be performed in specialized hospitals with experienced teams. Until we are able to prevent orthopedic problems of the knee in PWH will have to continue performing orthopedic procedures (arthrocentesis, RS, arthroscopic synovectomy, hamstring release, arthroscopic debridement, alignment osteotomy, and total knee arthroplasty). By using the aforementioned procedures, the quality of life of PWH will be improved.

Keywords: Hemophilia, Knee, Orthopedic problems, Prevention, Surgical treatment

Core tip: Hemophilia is an inherited bleeding disorder due to deficiency of factor VIII (hemophilia A) or factor IX (hemophilia B) resulting in insufficient thrombin generation leading to recurrent intra-articular hemorrhages (hemarthroses). Prevention of hemarthroses with intravenous infusions of the deficient protein from infancy to adulthood (primary prophylaxis) should be considered to achieve optimal outcomes. If factor replacement therapy (FRT) is insufficient, or if patients are not adherent to the prescribed regimen, recurrent hemarthroses results in chondrocyte apoptosis (cartilage degeneration) and hypertrophy of the synovium (synovitis). Many surgical interventions are available for the knee joint. For example, to treat synovitis recalcitrant to FRT, there are two primary orthopedic modalities: Radiosynovectomy and arthroscopic synovectomy. This article reviews the pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment of hemophilic arthropathy of the knee.

INTRODUCTION

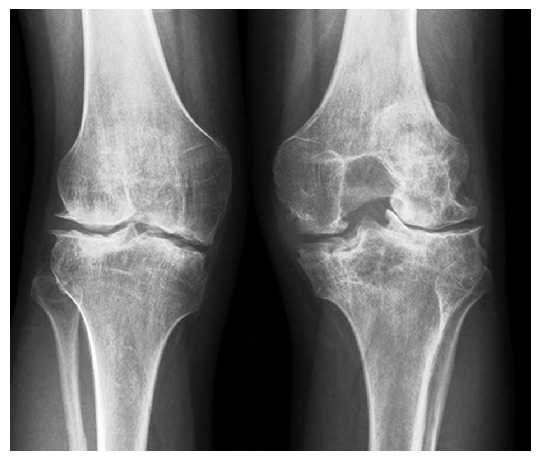

Hemophilic arthropathy (HA) in one or more joints, mainly ankles, elbows and knees affects about 90% of people with hemophilia (PWH) by 20-30 years of age (Figure 1). Recurrent bleeding into joints (hemarthroses) results in progressive, proliferative and degenerative articular changes. To prevent these complications, regular factor replacement therapy (FRT) with the deficient protein from an early age (primary prophylaxis) is the key to prevent synovitis and HA. However, despite primary prophylaxis, some PWH suffer from clinical bleeding due to an insufficient dosing regimen or non-adherence while others may experience subclinical joint bleeding. Although the pathogenesis of HA is not fully understood[1], it is generally assumed that primary prophylaxis prevents bleeding and HA[2,3].

Figure 1.

Severe bilateral hemophilic arthropathy of the knee in a 37-year-old male.

There are multiple strategies for implementing primary prophylaxis in young children with severe hemophilia including once-weekly injections which has the advantage of avoiding the implantation of a central venous access device in very young children. Unfortunately, this regimen fails to prevent joint bleeding in all but a few children and most develop HA[4].

Prophylaxis must begin early in life because even infrequent or a short durations of blood in contact with cartilage can cause chondrocyte apoptosis that can eventually lead to HA. Once developed, HA can be addressed with basic surgical procedures including radiosynovectomy (RS), chemical synovectomy (CS), arthroscopic synovectomy (AS), arthroscopic joint debridement and total knee arthroplasty (TKA)[5,6].

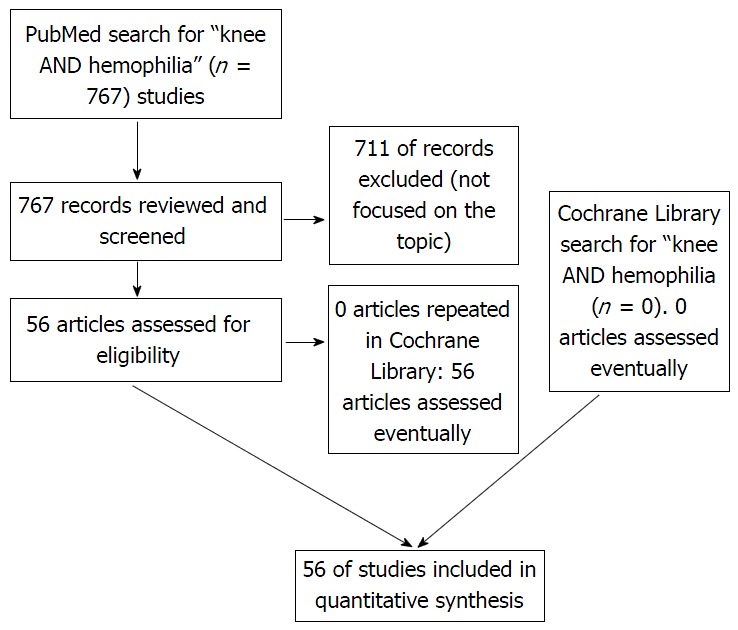

RESEARCH

A literature review of knee disorders in patients with hemophilia was performed using MEDLINE (PubMed) and the Cochrane Library. The keywords used were “knee” and “hemophilia”. The time period of the searches was from the beginning of the availability of the search engines until 31 December 2015. A total of 767 articles were found, of which 56 were selected and reviewed because they were deeply focused on the topic. The flow diagram of the study is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Flow chart of our search strategy.

PATHOGENESIS

Chronic hemophilic synovitis (CHS) and cartilage destruction are the main findings of HA, both phenomena due to severe or recurrent hemarthroses. The precise pathogenesis of CHS and HA remains poorly understood. Ex vivo studies with canine cartilage suggest that a 4-d duration of blood exposure produces loss of cartilage matrix[7]. Experimental studies have also demonstrated that after a major hemarthrosis the joint cavity is filled with a dense inflammatory infiltrate, and the tissues become brown-stained due to hemosiderin deposition following the breakdown of erythrocytes[8,9]. Vascular hyperplasia takes place resulting in tenous and friable vessels prone to bleed creating a viscous cycle of bleeding-vascular hyperplasia-bleeding. The articular surface becomes rugose with pannus formation and the subchondral bone becomes dysmorphic. After about one month, cartilage and bone erosions are evident.

It has been reported that the loading of the affected joint may play a role in the mechanism of cartilage degeneration in hemophilia[10]. Other authors have found that molecular changes induced by iron in the blood could explain the increase in cell proliferation in the synovial membrane (synovitis)[11]. Valentino et al[12] found in an experimental murine model that hemorrhage induced by a controlled, blunt trauma injury leads to causes joint inflammation, synovitis and HA.

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of CHS is usually made following examination of the knee with typical signs of joint swelling and warmth but with or without painful symptoms and reductions in motion of the knee. Ultrasonography (US) can be used to demonstrate hypertrophy of the synovium and the presence of fluid[13,14]. However, validation of US for the assessment of HA has not been established yet[15-17]. Magnetic resonance imaging is the gold standard for the diagnosis of synovitis.

ORTHOPEDIC TREATMENT

CHS

Celecoxib: Rattray et al[18] reported that celecoxib is effective in treating hemophilic synovitis, although the mechanism for this effect remains to be determined and these findings require controlled trials to be confirmed.

RS: RS is the optimal choice for treatment of patients with CHS, even in patients with anti-factor antibodies (inhibitors)[19-23]. The current recommendation is to use Yttrium-90 for the knees and Rhenium-186 for elbows and ankles and is supported by more than 40-years of experience with RS by the authors, who believe that the procedure is safe, easy to perform and economical technique for the management of CHS.

CS: Many chemical agents have been proposed to scar the synovium of patients with CHS including oral D-penicillamine[24]. A short-term period (3-6 mo) of treatment at a dose of 5-10 mg/kg per day for children and less than 750 mg/d for adults (one hour before breakfast) was recommended. The efficacy of this treatment needs further clinical trial data before it will gain widespread use. Oral D-penicillamine may be especially useful in patients with inhibitors. Another method to perform CS is by means of intra-articular injections of rifampicin[25] or oxytetraycline[26]. Alternative, RS is a favorable alternative to oral D-penicillamine and to rifampicin or oxytetracycline for synovectomy, because its efficacy has been proven over the last 40 years[27].

AS: The goal of AS is to reduce the number of hemarthroses in order to maintain the range of motion of the knee joint. However, AS cannot prevent joint degeneration[28-32].

Advanced HA

Open and arthroscopic debridement: Both open and arthroscopic debridement with synovectomy has been used in PWH between 20 and 40 years of age, with improvement in pain lasting several years, delaying the need of a TKA[33-35].

Hamstring release: Fixed knee flexion contracture is a common complication in PWH and hamstring tenotomy in association with posterior capsulotomy may be used to improve ambulation by reducing the contraction[36,37].

External fixation for flexion contracture: More drastic measures have also been used to reduce flexion contractures. For example, Kiely et al[38] reported the case of a 13-year-old boy with hemophilia who underwent Ilizarov external fixator with improvement of his knee flexion contracture. In this case, progressive extension reduced the contracture from 50 to 5 degrees.

Osteotomies around the knee: Malalignment of the lower limb is common in hemophilia patients and osteotomy around the knee (proximal tibia, distal femur) has resulted in improvements in gait and reduction in painful symptoms[39-42].

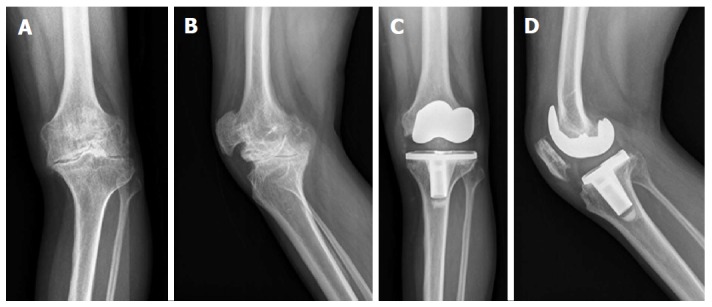

TKA: Unfortunately, many patients with knee HA continue to deteriorate resulting in life-altering knee pain. For these individuals, TKA is the treatment of choice and has resulted in dramatic improvements in patients with severe HA[43-49]. Therefore, TKA is an excellent option for the treatment of advanced HA of the knee (Figure 3). However the procedure is not without risk as the rate of infection after TKA is 7% on average.

Figure 3.

Severe painful hemophilic arthropathy of the left knee in a 41-year-old male. A cemented total knee arthroplasty (NexGen, Zimmer, United States) was performed with a satisfactory result: A: Anteroposterior preoperative radiograph; B: Lateral preoperative view; C: Anteroposterior radiograph 5 years later; D: Lateral view at 5 years. The quality of life of this patient improved significantly.

HEMATOLOGICAL PERIOPERATIVE TREATMENT

In major orthopedic procedures the preoperative levels of the deficient factor should be maintained at 80%-100%. In the postoperative period factor level must be over 50% in the two weeks and 30% later on, at least until wound healing (removal of staples)[50,51]. Continuous infusion of the deficient factor is better than bolus infusion[52,53] however mechanical malfunction of the venous line and pump must be guarded against. In patients with inhibitors there are two potential hematological treatments: Recombinant factor VII activated or Factor Eight Inhibitor Bypassing Agent[54-57].

CONCLUSION

The best treatment for PWH is primary prophylaxis replacing the deficient clotting factor with early institution of regular injections of concentrates of factor VIII or IX. In this way, not only is bleeding into the joints prevented but also the development of synovitis and articular degeneration (HA). For CHS recalcitrant to aggressive factor replacement, RS must be considered the first option and alternatively, AS. Surgery in PWH has a high risk of bleeding and infection. This kind of surgery must be performed with FRT in a specialized center. This way we will improve the quality of life of PWH minimizing the risk of complications.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest for this article.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: January 12, 2016

First decision: March 1, 2016

Article in press: April 22, 2016

P- Reviewer: Ohishi T, Samulski RJ, Zak L S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

References

- 1.Lafeber FP, Miossec P, Valentino LA. Physiopathology of haemophilic arthropathy. Haemophilia. 2008;14 Suppl 4:3–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2008.01732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nilsson IM, Berntorp E, Löfqvist T, Pettersson H. Twenty-five years’ experience of prophylactic treatment in severe haemophilia A and B. J Intern Med. 1992;232:25–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1992.tb00546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manco-Johnson MJ, Abshire TC, Shapiro AD, Riske B, Hacker MR, Kilcoyne R, Ingram JD, Manco-Johnson ML, Funk S, Jacobson L, et al. Prophylaxis versus episodic treatment to prevent joint disease in boys with severe hemophilia. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:535–544. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kraft J, Blanchette V, Babyn P, Feldman B, Cloutier S, Israels S, Pai M, Rivard GE, Gomer S, McLimont M, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging and joint outcomes in boys with severe hemophilia A treated with tailored primary prophylaxis in Canada. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10:2494–2502. doi: 10.1111/jth.12025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hilgartner MW. Current treatment of hemophilic arthropathy. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2002;14:46–49. doi: 10.1097/00008480-200202000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodriguez-Merchan EC. Aspects of current management: orthopaedic surgery in haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2012;18:8–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2011.02544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jansen NW, Roosendaal G, Bijlsma JW, Degroot J, Lafeber FP. Exposure of human cartilage tissue to low concentrations of blood for a short period of time leads to prolonged cartilage damage: an in vitro study. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:199–207. doi: 10.1002/art.22304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valentino LA, Hakobyan N. Histological changes in murine haemophilic synovitis: a quantitative grading system to assess blood-induced synovitis. Haemophilia. 2006;12:654–662. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2006.01348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valentino LA, Hakobyan N, Rodriguez N, Hoots WK. Pathogenesis of haemophilic synovitis: experimental studies on blood-induced joint damage. Haemophilia. 2007;13 Suppl 3:10–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2007.01534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hooiveld MJ, Roosendaal G, Jacobs KM, Vianen ME, van den Berg HM, Bijlsma JW, Lafeber FP. Initiation of degenerative joint damage by experimental bleeding combined with loading of the joint: a possible mechanism of hemophilic arthropathy. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:2024–2031. doi: 10.1002/art.20284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hakobyan N, Kazarian T, Jabbar AA, Jabbar KJ, Valentino LA. Pathobiology of hemophilic synovitis I: overexpression of mdm2 oncogene. Blood. 2004;104:2060–2064. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valentino LA, Hakobyan N, Kazarian T, Jabbar KJ, Jabbar AA. Experimental haemophilic synovitis: rationale and development of a murine model of human factor VIII deficiency. Haemophilia. 2004;10:280–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2004.00899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Acharya SS, Schloss R, Dyke JP, Mintz DN, Christos P, DiMichele DM, Adler RS. Power Doppler sonography in the diagnosis of hemophilic synovitis--a promising tool. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6:2055–2061. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Querol F, Rodriguez-Merchan EC. The role of ultrasonography in the diagnosis of the musculo-skeletal problems of haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2012;18:e215–e226. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2011.02680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merchan EC, De Orbe A, Gago J. Ultrasound in the diagnosis of the early stages of hemophilic arthropathy of the knee. Acta Orthop Belg. 1992;58:122–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wallny T, Brackmann HH, Semper H, Schumpe G, Effenberger W, Hess L, Seuser A. Intra-articular hyaluronic acid in the treatment of haemophilic arthropathy of the knee. Clinical, radiological and sonographical assessment. Haemophilia. 2000;6:566–570. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2516.2000.00413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klukowska A, Czyrny Z, Laguna P, Brzewski M, Serafin-Krol MA, Rokicka-Milewska R. Correlation between clinical, radiological and ultrasonographical image of knee joints in children with haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2001;7:286–292. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2516.2001.00509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rattray B, Nugent DJ, Young G. Celecoxib in the treatment of haemophilic synovitis, target joints, and pain in adults and children with haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2006;12:514–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2006.01311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodriguez-Merchan EC, Wiedel JD. General principles and indications of synoviorthesis (medical synovectomy) in haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2001;7 Suppl 2:6–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2516.2001.00102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodriguez-Merchan EC, Luck JV Jr, Silva M, Quintana M. In: The Haemophilic Joints-New Perspectives. Rodriguez-Merchan EC, editor. Blackwell, Oxford; 2003. Synoviorthesis in haemophilia; pp. 73–79. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mortazavi SM, Asadollahi S, Farzan M, Shahriaran S, Aghili M, Izadyar S, Lak M. (32)P colloid radiosynovectomy in treatment of chronic haemophilic synovitis: Iran experience. Haemophilia. 2007;13:182–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2006.01424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De la Corte-Rodriguez H, Rodriguez-Merchan EC, Jimenez-Yuste V. Radiosynovectomy in hemophilia: quantification of its effectiveness through the assessment of 10 articular parameters. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:928–935. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de la Corte-Rodriguez H, Rodriguez-Merchan EC, Jimenez-Yuste V. What patient, joint and isotope characteristics influence the response to radiosynovectomy in patients with haemophilia? Haemophilia. 2011;17:e990–e998. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2011.02546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Corrigan JJ, Damiano ML, Leissinger C, Wulff K. Treatment of chronic haemophilic synovitis in humans with D-penicillamine. Haemophilia. 2003;9:64–68. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2516.2003.00676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Radossi P, Baggio R, Petris U, De Biasi E, Risato R, Davoli PG, Tagariello G. Intra-articular rifamycin in haemophilic arthropathy. Haemophilia. 2003;9:60–63. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2516.2003.00703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fernandez-Palazzi F, Viso R, Bernal R, Capetillo G, Caviglia H. In: The Haemophilic Joints-New Perspectives. Rodriguez-Merchan EC, editor. Blackwell, Oxford; 2003. Oxytetracycline clorhydrate as a new material for chemical synoviorthesis in haemophilia; pp. 80–83. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodríguez-Merchán EC. Orthopedic surgery is possible in hemophilic patients with inhibitors. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2012;41:570–574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wiedel JD. Arthroscopic synovectomy for chronic hemophilic synovitis of the knee. Arthroscopy. 1985;1:205–209. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(85)80013-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wiedel JD. Arthroscopic synovectomy of the knee in hemophilia: 10-to-15 year followup. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;328:46–53. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199607000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Journeycake JM, Miller KL, Anderson AM, Buchanan GR, Finnegan M. Arthroscopic synovectomy in children and adolescents with hemophilia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2003;25:726–731. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200309000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dunn AL, Busch MT, Wyly JB, Sullivan KM, Abshire TC. Arthroscopic synovectomy for hemophilic joint disease in a pediatric population. J Pediatr Orthop. 2004;24:414–426. doi: 10.1097/00004694-200407000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoon KH, Bae DK, Kim HS, Song SJ. Arthroscopic synovectomy in haemophilic arthropathy of the knee. Int Orthop. 2005;29:296–300. doi: 10.1007/s00264-005-0666-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Soreff J. Joint debridement in the treatment of advanced hemophilic knee arthropathy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1984;191:179–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rodriguez-Merchan EC, Gomez-Cardero P. Arthroscopic knee debridement can delay total knee replacement in painful moderate haemophilic arthropathy of the knee in adult patients. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2015 doi: 10.1097/MBC.0000000000000443. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rodriguez Merchan EC, Magallon M, Galindo E. Joint debridement for haemophilic arthropathy of the knee. Int Orthop. 1994;18:135–138. doi: 10.1007/BF00192468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rodríguez-Merchán EC, Magallón M, Galindo E, López-Cabarcos C. Hamstring release for fixed knee flexion contracture in hemophilia. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997;34:63–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pennekamp PH, Wallny TA, Goldmann G, Kraft CN, Berdel P, Oldenburg J, Wirtz DC. [Flexion contracture in haemophilic knee arthropathy--10-year follow-up after hamstring release and dorsal capsulotomy] Z Orthop Unfall. 2007;145:317–321. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-965228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kiely PD, McMahon C, Smith OP, Moore DP. The treatment of flexion contracture of the knee using the Ilizarov technique in a child with haemophilia B. Haemophilia. 2003;9:336–339. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2516.2003.00753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rodriguez Merchan EC, Galindo E. Proximal tibial valgus osteotomy for hemophilic arthropathy of the knee. Orthop Rev. 1992;21:204–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Caviglia HA, Perez-Bianco R, Galatro G, Duhalde C, Tezanos-Pinto M. Extensor supracondylar femoral osteotomy as treatment for flexed haemophilic knee. Haemophilia. 1999;5 Suppl 1:28–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2516.1999.0050s1028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wallny T, Saker A, Hofmann P, Brackmann HH, Nicolay C, Kraft CN. Long-term follow-up after osteotomy for haemophilic arthropathy of the knee. Haemophilia. 2003;9:69–75. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2516.2003.00705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mortazavi SM, Heidari P, Esfandiari H, Motamedi M. Trapezoid supracondylar femoral extension osteotomy for knee flexion contractures in patients with haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2008;14:85–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2007.01585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sheth DS, Oldfield D, Ambrose C, Clyburn T. Total knee arthroplasty in hemophilic arthropathy. J Arthroplasty. 2004;19:56–60. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rodriguez-Merchan EC, Luck JV Jr, Silva M, Riera JA, Wiedel JD, Goddard NJ, Heim M, Solimeno PL. In: The Haemophilic Joints.-New Perspectives. Rodriguez-Merchan EC, editor. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford; 2003. Total knee replacement in the haemophilic patient; pp. 116–124. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Norian JM, Ries MD, Karp S, Hambleton J. Total knee arthroplasty in hemophilic arthropathy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-A:1138–1141. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200207000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ragni MV, Crossett LS, Herndon JH. Postoperative infection following orthopaedic surgery in human immunodeficiency virus-infected hemophiliacs with CD4 counts & lt; or = 200/mm3. J Arthroplasty. 1995;10:716–721. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(05)80065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rodriguez-Merchan EC. Total knee arthroplasty in patients with haemophilia who are HIV-positive. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:170–172. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.84b2.13015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Powell DL, Whitener CJ, Dye CE, Ballard JO, Shaffer ML, Eyster ME. Knee and hip arthroplasty infection rates in persons with haemophilia: a 27 year single center experience during the HIV epidemic. Haemophilia. 2005;11:233–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2005.01081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rodríguez-Merchán EC. Total Knee Arthroplasty in Hemophilic Arthropathy. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2015;44:E503–E507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jimenez-Yuste V, Rodriguez-Merchan EC, Alvarez-Roman MT, Martin-Salces M. In: Joint Surgery in the Adult Patient with Hemophilia. Rodriguez-Merchan EC, editor. Springer International Publishing Switzerland; 2015. Hematological concepts and hematological perioperative treatment; pp. 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wong JM, Mann HA, Goddard NJ. Perioperative clotting factor replacement and infection in total knee arthroplasty. Haemophilia. 2012;18:607–612. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2011.02728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Martinowitz U, Schulman S, Gitel S, Horozowski H, Heim M, Varon D. Adjusted dose continuous infusion of factor VIII in patients with haemophilia A. Br J Haematol. 1992;82:729–734. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1992.tb06951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Batorova A, Martinowitz U. Intermittent injections vs. continuous infusion of factor VIII in haemophilia patients undergoing major surgery. Br J Haematol. 2000;110:715–720. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jiménez-Yuste V, Rodriguez-Merchan EC, Alvarez MT, Quintana M, Fernandez I, Hernandez-Navarro F. Controversies and challenges in elective orthopedic surgery in patients with hemophilia and inhibitors. Semin Hematol. 2008;45:S64–S67. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stephensen D. Rehabilitation of patients with haemophilia after orthopaedic surgery: a case study. Haemophilia. 2005;11 Suppl 1:26–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2005.01151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.De la Corte-Rodriguez H, Rodriguez-Merchan EC. The role of physical medicine and rehabilitation in haemophiliac patients. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2013;24:1–9. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0b013e32835a72f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rodriguez-Merchan EC, Rocino A, Ewenstein B, Bartha L, Batorova A, Goudemand J, Gringeri A, Joao-Diniz M, Lopaciuk S, Negrier C, et al. Consensus perspectives on surgery in haemophilia patients with inhibitors: summary statement. Haemophilia. 2004;10 Suppl 2:50–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2004.00941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]