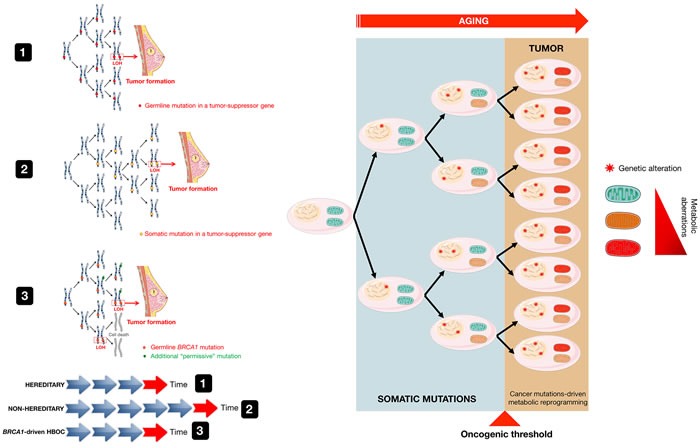

Figure 1. Hits and tumor formation in hereditary and nonhereditary carcinomas.

The mechanisms that underline genetic predisposition to cancer were originally clarified by Knudson, who hypothesized that germline mutations occur in one allele of a tumor suppressor gene followed by somatic inactivation, or loss of function, of the remaining normal allele through mutations, deletions, or epigenetic repression (defined as loss of heterozygosity [LOH]) [15] (model 1). The Knudson “two-hit” hypothesis has been largely validated in most forms of autosomal hereditable cancer and has been also extended to sporadic forms of cancer, albeit at a greater level of complexity [84]. Because in the nonhereditary scenario, the first somatic mutation might be expected to occur at a rate approximately equal to that of the second mutation in the hereditary cases, a “one-hit” clone is a precursor to the tumor formation in nonhereditary forms of cancer (model 2), whereas all cells are “one-hit” clones in hereditary cancer syndromes. BRCA1-driven HBOC syndrome, however, apparently contradicts the original “two-hit” theory conformed by other familial cancer syndromes, in which consecutive deletion of two alleles accelerates tumorigenesis. Cancer predisposition upon inactivation of a single BRCA allele relates to the so-called haploinsufficiency phenomenon associated with heterozygosity, which results in genomic instability in breast/ovarian epithelial cells. This in turn may promote additional genetic changes in BRCA heterozygous cells, including the acquisition of new mutations that will precede and be permissive with the loss of BRCA (e.g., p53, ATM and CHK2) (model 3). The requirement of this “extra-hit”, although incongruous from the viewpoint of familial tumorigenesis mediated by tumor suppressor genes such as BRCA1 and BRCA2, appears to enable cancer-prone BRCA “one-hit” cells to evade the cell death processes that would otherwise occur upon loss of the remaining wild-type allele. Based on these models, cancer metabolic reprogramming is not the cause but rather the consequence of the mutations that originally generated malignancy and tumor growth (modified from original drawing published by Lindsay et al. [19]).