Abstract

In countries such as the USA, gay and bisexual men experience high rates of intimate partner violence. However, little is known about the factors that contribute to this form of violence. In this study, we examine gay and bisexual men’s perceptions of sources of tension in same-sex male relationships and how these may contribute to intimate partner violence. We conducted seven focus group discussions with 64 gay and bisexual men in Atlanta, GA. Focus groups examined men’s reactions to the short-form revised Conflicts Tactics Scale to determine if each item was considered to be intimate partner violence if it were to occur among gay and bisexual men. Analysts completed a thematic analysis, using elements of grounded theory. The sources of tension that men identified included: gender role conflict, dyadic inequalities (e.g. differences in income, age, education), differences in ‘outness’ about sexual identity, substance use, jealousy, and external homophobic violence. Results suggest that intimate partner violence interventions for gay and bisexual men should address behavioural factors, while also focusing on structural interventions. Interventions that aim to reduce homophobic stigma and redefine male gender roles may help to address some of the tension that contributes to intimate partner violence in same-sex male relationships.

Keywords: intimate partner violence, gay and bisexual men, gender, masculinity, same-sex male couples, USA

Introduction

Intimate partner violence is generally defined as interpersonal violence occurring between intimate partners and may include multiple domains of violent behaviour (e.g. physical, sexual, psychological, financial, and stalking). Intimate partner violence is a serious public health problem, with links to increased morbidity and mortality, including physical trauma and injury, sexually transmitted infections, chronic pain, and poor mental health outcomes (Coker 2007, Coker et al. 2002, Plichta 2004, Tjaden and Thoennes 2000). Considerable attention has been paid to intimate partner violence within heterosexual relationships and the socio-cultural, individual, and dyadic forces that predict violence perpetration and victimisation (Jewkes 2002).

There is growing evidence that intimate partner violence is a public health problem among gay and bisexual men, with recent studies suggesting that gay and bisexual men experience intimate partner violence at similar or even higher rates than have been documented among heterosexual women (Finneran and Stephenson 2013). However, intimate partner violence among gay and bisexual men has been under-researched, resulting in a lack of consensus on key conceptual issues such as the definition, range, scope, and severity of violence (Finneran and Stephenson 2013). In their review of 28 epidemiological studies, Finneran and Stephenson report that the prevalence of perpetration or receipt of any intimate partner violence among gay and bisexual men varies from 30% to 78%, with estimates of experiencing violence vastly outweighing estimates of perpetration (Finneran and Stephenson 2013). Previous studies have also examined ways in which health outcomes of intimate partner violence can be unique to gay and bisexual men, identifying how it may increase substance use, HIV risk, and depression (Buller et al. 2014).

Much research has examined the factors that contribute to intimate partner violence in heterosexual relationships. A key theme in the literature on heterosexual IPV is power and control (Felson and Outlaw 2007), with many studies suggesting that men deploy violence in a repeated and calculated manner in order to maintain or reinforce their control over women in a relationship (Stark 2007). Stark presents the concept of coercive control, which highlights how intimate partner violence is not just a series of violent incidents, but rather occurs when male perpetrators of violence combine repeated physical abuse with intimidation, isolation, and control. These coercive behaviours may lead to “women’s entrapment” because they physically and psychologically harm women and deprive them of “rights and resources that are critical to personhood and citizenship” (Stark 2007).

It remains unknown how the concept of coercive control applies to same-sex male relationships; however, there has been some research to explain the factors that contribute to intimate partner violence among gay and bisexual men (Craft and Serovich 2005, Finneran and Stephenson 2014, Relf 2001, Welles et al. 2011). In a study by Finneran et al., gay and bisexual men identified 24 proximal antecedents of intimate partner violence, which were characterised into four factors: power and negotiation characteristics, relationship characteristics, life stressors, and threats to masculinity (Finneran and Stephenson 2014). Other studies have also examined links between early experiences of violence as a possible predictor of intimate partner violence victimisation and perpetration among gay and bisexual men (Welles et al. 2011, Craft and Serovich 2005). Some of these antecedents may be similar to those typically examined in heterosexual relationships (Holt, Buckley, and Whelan 2008, Mason and Blankenship 1987); however, further research is needed to understand the context of how these antecedents are experienced among gay and bisexual men. In this study, we use data from focus group discussions to explore gay and bisexual men’s perceptions of the sources of tension that exist in same-sex male relationships and examine the ways in which they may contribute to intimate partner violence among gay and bisexual men. The results presented do not intend to capture the personal experiences of those perpetrating or experiencing intimate partner violence, but rather focus on the general perceptions that gay and bisexual men have about intimate partner violence in their communities. Understanding gay and bisexual men’s perceptions of how sources of tension influence intimate partner violence among gay and bisexual men can help to inform interventions to address intimate partner violence in this population and has the potential to refine measurements used to understand intimate partner violence in same-sex male relationships.

Methods

This study was approved by the ______ University Institutional Review Board. We chose to use focus groups because we were examining gay and bisexual men’s general perceptions of intimate partner violence in their communities. This method allows for an interpretive descriptive analysis (Sandelowski 2000) to understand how gay and bisexual men perceive intimate partner violence. Despite the sensitive topic of intimate partner violence, focus groups discussions are appropriate for examining general perceptions (Kitzinger 1995).

Recruitment and Population

We recruited gay and bisexual men in Atlanta, GA using a venue-based sampling. Venue-based sampling is a derivative of time-space sampling, in which sampling occurs within prescribed blocks of time at previously-identified venues at which ‘hard-to-reach’ populations frequently congregate (Muhib et al. 2001). The venue sampling frame consisted of a variety of over 160 gay-themed or gay-friendly venues, including Gay Pride events, gay sports teams events, gay fundraising events, downtown areas, gay bars, bathhouses, an AIDS service organisation, and urban parks. Study recruiters stood adjacent to the venue, drew an imaginary line on the ground, and approached every nth man who crossed it; n varied between one and three depending on the volume of traffic at the venue. If a man agreed to be screened, he was then asked a series of questions to assess his eligibility. Eligibility criteria included being a man aged 18 years or older, who self-identifies as gay or bisexual, and lives in the metropolitan area of Atlanta, GA. Eligible men were then read a short script that described the study process. Interested participants were later contacted to participate in a focus group discussion.

Data Collection

We conducted seven focus group discussions with a total of 64 men, with 8–13 men per group. We originally scheduled eight focus groups, but we combined the last two due to scheduling issues resulting in one focus group with 13 participants. All other groups consisted of 8–9 participants. Data analysts checked for saturation of data as focus groups were being conducted and the question guide was edited to refocus the questioning on areas that were not saturated as the groups progressed. All focus groups were conducted by a trained moderator at _______ University; the moderator was a white gay male with extensive qualitative research experience. Each focus group discussion lasted approximately one and a half hours and discussions centred on understanding definitions of intimate partner violence. The question guide was based on the short-form revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2) questions (Straus and Douglas 2004), a commonly-used scale for measuring intimate partner violence (Stephenson and Finneran 2013, Yun 2010). Participants were asked if they would consider each item on the scale to be intimate partner violence (for both victimisation and perpetration of intimate partner violence) if it were to occur in a same-sex male relationship, and what other forms of intimate partner violence may occur in male same-sex relationships that were not present in the CTS2. While the CTS2 has its limitations (Archer 1999, Straus 1990), the widely-used scale was a useful source to prompt discussion and better understand men’s perceptions about intimate partner violence in same-sex male relationships. Further questions examined participants’ definitions of sexual, physical, and psychological intimate partner violence and controlling/stalking behaviours.

Analytic Strategy

Focus group discussions were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. We used qualitative data analysis software, MAXQDA, version 10 (Verbi Software, Berlin, Germany) to aid analysis. We conducted a thematic analysis using some elements of grounded theory (Charmaz and Smith 2003). To identify salient themes, we incorporated both deductive and inductive strategies. Deductive codes were created based on possible causes of violence, expressions of violence, and contributions or underlying social, cultural, and economic factors that may make violence more or less likely. After multiple close readings, inductive codes were also identified to represent unexpected reoccurring themes that occurred throughout the text (Bernard and Ryan 2010). All inductive and deductive codes were clearly defined and two analysts applied the codes to the text in order to segment data based on theme. Consistency between coding was examined and discrepancies were solved based on consensus. Data were closely reviewed, comparing and contrasting themes within and between participants and focus group discussions. Thick descriptions of each code were developed and representative quotes were used to identify common concepts, contrasting ideas, and unique viewpoints.

Findings

Participant demographics are described in Table 1. There was a variety of responses about awareness of intimate partner violence in same-sex male relationships. Even though the purpose of this study was to understand general perceptions of intimate partner violence in same-sex male relationships, many participants identified first- or second hand examples of violence occurring within relationships; however several participants noted that they had not heard of any type of violence occurring in same-sex male relationships. Several men described a general trajectory that culminated in violent acts. Typically this began with verbal abuse and occasionally other forms of emotional abuse (e.g. psychological aggression, coercive control), then moved to physical and then sexual abuse, which was widely viewed by participants to be “more extreme” than the other forms. Participants discussed six sources of tension that they believed contributed to violence in a relationship, including 1) gender role stereotypes; 2) dyadic inequalities in income, employment, age, etc.; 3) dyadic differences in outness; 4) alcohol and drugs; 5) jealousy; and 6) external homophobic violence. Although we describe these as freestanding themes, in many cases, these themes also interact with each other.

Table 1.

| Mean | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 32 | 21–47 |

| Race | % | n |

| African American/Black | 53 | 34 |

| Caucasian/White | 47 | 30 |

| Sexual Orientation | ||

| Gay | 95 | 61 |

| Bisexual | 5 | 3 |

| Employment | ||

| Employed | 64 | 41 |

| Unemployed | 36 | 23 |

| Education | ||

| College education or higher | 38 | 24 |

| Less than college education | 62 | 40 |

| Relationship status | ||

| Single | 45 | 29 |

| In a relationship | 55 | 35 |

Gender roles and gender role conflict

Participants described normalised gender roles as contributing to intimate partner violence in same-sex male relationships. Participants perceived that men ascribe to a form of masculinity in which they are “dominant” and “violent” beings. They stated that intimate partner violence would be greater in same-sex male relationships because both individuals are more violent:

“It’s two men [another man chimes in: “Men are dominant creatures”] you still have two men, whether one is more flamboyant [than] the other, the testosterone is there, whether they hide it or suppress it, you still dealing with two men” (FGD 7).

Participants also identified that societal gender norms and expectations about masculinities make it difficult to recognise and address intimate partner violence in same-sex male relationships:

“Society looks, just frowns down on that type of abuse [men beating women], but, in abuse between two men, it’s like, it’s two men [others are agreeing here] it’s like, fight back, you’re a man, who you crying, you perceived to be weak if you go crying about it, or go to the cops, or call the cops, or you don’t defend yourself, you perceived to be weak” (FGD 2).

According to participants, experiencing intimate partner violence is not perceived as masculine and therefore presents a challenge for men to identify it. Participants reported that men’s perceived ability to fight back means that they are unable to experience intimate partner violence or that only “weak” men experience intimate partner violence.

Though men talked about ascribing to a dominant form of masculinity, men also identified a lack of clearly defined gender roles for same-sex male couples because stereotypical gender roles are heteronormative; this was especially problematic when considering household roles. Men reported that for heterosexual couples, the perception of normative patterning of roles is well established and the end point is frequently children: “with male-female, it’s like, you date, you get engaged, you get married, you have kids.” Men identified these stereotypes as serving a purpose in heterosexual relationships: “I mean we don’t have the luxury of relying on a stereotype.” The lack of these clearly defined roles for same-sex male relationships was described as creating conflict:

“It’s alpha and beta basically, in the relationship, and that usually can sometimes cause conflict as well. Who’s going to take the leadership role? Even if it goes back and forth, but, at times, it can get complicated, and you’re both struggling to be the alpha in situations of religion or money and everything, and that’s where conflict usually occurs” (FGD 1).

According to participants’ perceptions of intimate partner violence in same-sex male relationships, this ongoing tension can contribute to intimate partner violence; as some participants stated, identifying who will be the “leader” of the household can turn into a “battle.”

Dyadic differences in income, education, employment, or age

Since, according to participants, same-sex male couples cannot rely on gender stereotypes to determine who is the dominant partner, this dominance was described as being determined by other inequalities. Men stated that when inequalities between men were greater, the threat of violence was greater. The most commonly mentioned inequalities were money, education, employment, and age. Inequalities were perceived as adding additional strain to a relationship: “I would think it [inequalities] can add to a stressful situation especially if one person makes significantly more money, or if one of the persons is unemployed.” These tensions in inequalities (especially financial inequalities) could be exacerbated when there were financial strains in the relationships. Several men reported that conflict was more apt to develop and escalate into violence when there was “not enough money.”

Inequalities were linked to violence in two ways. First, inequalities led to differences in power, which then were thought to spill over into abuse and various forms of violence. In these examples, many participants described scenarios where one partner would use money to gain more power in the relationship and control the other partner:

“I’ve actually been in a relationship where a guy has said, ‘I’ll buy you anything you want,’ and I said ‘Whoa.’ I said, ‘No, I don’t need you to buy me, I can take care of myself.’ Y’know, so I think sometimes might use that to lord stuff over you to try to control you and say, ‘Well look, I’ve done this for you, so how can you say no to me when I ask you to do anything?’” (FGD 1).

“I can see where the person who makes more might feel like they have more control over the relationship, and then might be more apt to become violent, cause they think they can get away with it” (FGD 5).

This concept of control was not only applied to financial inequalities, but also other dyadic differences, such as age and nationality:

“My ex-boss, he was about 50, and he has a little house boy that he calls his partner, for two years, and he was only about 25, doesn’t have a college degree, doesn’t have a job, and I don’t think he’s even here in the state legally, so, we would see a lot of physical abuse, where the relationship got so bad that the 25 year old just said I had enough of this, y’know, two years of hell, and he actually broke my boss’s nose, and actually had knife and weapon because… he just couldn’t deal with it any more, it just got so bad that the mental violence, that, y’know, the passive aggressive, that ‘if you don’t do this I’m gonna report you, I’m gonna deport you,’ whatever, had just gotten so bad that he just finally said enough” (FGD 5).

In this case, the exertion of power and violence led to additional violence that resulted from the partner being victimised.

This example also relates to the second way in which inequalities were linked to violence: inequalities were thought to limit one’s ability to exit a violent relationship. In the example of the ex-boss, the victimised partner had little power and difficulty leaving, until violence finally escalated. More commonly, participants described this inability to exit when one participant was supporting the other financially; one participant stated, “How I gonna pay my apartment, my tuition, my cell phone bill if I’m not with this person?” Another participant discussed how age inequality in a friend’s “extremely sexually abusive” relationship made it difficult for the younger partner (who was experiencing the abuse) to exit the relationship:

“Probably twice his age, my friend was, in his early, early 20s, his partner was in his 40s, totally closeted, financially secure… my friend was still in college and depended heavily on him and he used the financial control to kind of keep him in the relationship” (FGD 6).

According to participants, the power differences between partners and the difficulty to exit worked in tandem, with one man exercising his power while the other is unable to exit a relationship.

Dyadic differences in outness

Participants also described dyadic differences in outness about sexual identities as contributing to intimate partner violence (i.e. if one partner is “out” and the other is not). When discussing this dyadic difference, there was some disagreement among participants regarding which partner (the in partner versus the out partner) would be more likely to perpetrate intimate partner violence. Rather than identifying one partner as more likely to be the perpetrator or the victim, many participants across focus groups stated that how differences in outness could enable “mutual violence” by creating circumstances in which both the in partner and the out partner may perpetrate violence; men recognised that both partners would have the “tools” for being violent, but ultimately the partner with more control/power and likelihood to abuse was the partner that had a more “manipulative” personality and “has the initiative” to use those tools to control their partner. In some cases, participants identified different circumstances for how one partner or the other would be the perpetrator, but in many cases, circumstances were identified where both partners could perpetrate violence.

In all focus group discussions, participants recognised that the possibility for the in partner’s identity to be disclosed could be a source of tension that could contribute to intimate partner violence. On the one hand, this creates a power imbalance, with the out partner having more power because he can threaten to disclose his partner’s sexual identity to others. Some participants described these threats as leading to intimate partner violence or “conflict,” while other participants identified this as an act of psychological or emotional violence:

“At least that social or that more controlling factor about being abusive around, ‘Ok, if you don’t do what I’m telling you to do, I’m gonna tell everybody that you’re gay,’ kind of thing…. At least the abusive nature, whether he becomes violent or not, that’s, y’know, depends, but certainly, that individual is more likely to be more controlled because of the situation which they find themselves in” (FGD 3).

“The in guy could definitely have more violence because the out guy could easily out him to anybody, to his family, to his friends, to his co-workers, and that could lead to his family jumpin’ on him, his co-workers jumpin’ on him. People just gay-bashing” (FGD 5).

On the other hand, participants also noted that the in partner’s fear of being outed could contribute to “the one who is closeted [being] more violent.” Participants stated that intimate partner violence could occur from the in partner when they were concerned about being outed, even when the out partner had not threatened to disclose their identity:

“I had an incident, where, me and my friend we was out. And, I mean, I looked gay, or whatever, but [my partner] was, on the DL and he saw somebody that he knew from school, and so he tried to speed up or whatever, and then, I called him out, basically, and then he wanted to fight me” (FGD 4).

In addition, participants also stated that a fear of being outed could contribute to the in partner controlling the out partner. Participants described situations in which the out partner would “adapt” to the in partner and it would influence “what they want to do, places they wanna go, how they wanna act, and who they can interact with.” Participants explained that these types of Behaviours could be psychologically abusive, especially if they cause the out partner to remain “closeted” while in the relationship:

“I had a friend who did this, he moved here, he was out with his family and everything…and his boyfriend, who was in the closet and who was gay, dated and said, ‘I’ll only date if you pretend you’re straight,’… And his whole self-esteem went down, he was like what am I, but he did that for 2 years, and even now he’s like I don’t know what I did, so, in that way it was controlling, and, I don’t know if it was violent, but it was abusive in a way psychologically, because he played the card and ‘to stay with me you have to stay in the closet’” (FGD 6).

In all focus group discussions, participants also discussed how a difference in outness creates a tension in the relationship where the out partner cannot fully be a part of the in partner’s life. Participants agreed that the in partner may perpetuate emotional violence by “shunning” their partner, by acting “ashamed” of the relationship, and by not “respecting” them enough to be out about their relationship. However, participants disagreed on how this tension would lead to violence. Some participants stated that this is act of “shunning” is emotional violence, while other participants noted that the out partner may feel badly and respond to this with violence:

“P1: My experience is, the person who is out will be more in risk to violence, because the in guy, y’know, he’s still in the closet, he doesn’t want to let other people know… if you’re still in the closet with your family and your friends, then that causes a lot of issues… you can’t introduce, you can’t bring your friends in the house because your partner’s not out, or you can’t bring your family in the house because your partner is, lacks that self-confidence to be able to tell, y’know, who exactly he is. So the person who is out will be more likely to be in a type of relationship where he might be get affected. Or be affected.

P2: See I think the in guy would be more affected by violence because the out guy’s gonna be like, well, more in his face about like why aren’t you allowing me to be a part of this part of your life?” (FGD 5).

According to participants, a third way that differences in outness could influence intimate partner violence is through an imbalance of power where the out partner has more of a social support system than the in partner. Participants agreed that this tension would cause the in partner to be more vulnerable to experiencing intimate partner violence from their out partner. Few participants explicitly described this concept but one person did explain that in his last two relationships, his partners were not out. The participant explained that he was the only source of support for his partners, who in turn leaned on him heavily for support and advice. As a result, the power dynamics in the relationship became very unbalanced, until the man who was out “basically wore the pants in the family” while the other partner “felt like nothing.” Men also recognised that this lack of support system would make it more difficult for the in partner to report abuse because that would publicise his sexual identity: “I think someone in the closet is less likely to report, because of, y’know, you might have to go through a court, and tell your story in front of everybody, and your family may be involved.”

Participants also stated that differences in outness could lead to intimate partner violence because the in partner may be more violent due to the insecurities, inner turmoil, and stress that being “closeted” generated:

“If you haven’t gotten to the point where you accept yourself enough, I think you probably might have more potential for that [violence]” (FGD 3).

“Being in the closet would create a level of tension that might make anger outburst easier. Or more frequent” (FGD 3).

A few participants noted that this tension may be especially salient for African American men, who they perceived as being less accepting of homosexual relationships:

“It seems like in the African-American community it’s…not as acceptable to be out, it’s not as acceptable to be gay, I think, there’s a looot higher percentage of people that are in the closet I think, again, that introduces an inner turmoil, they force outward. I think that’s what, in my opinion, that’s what causes the violence” (FGD 6).

Alcohol and drugs

Alcohol and drug use by one or both partners was also widely viewed as catalysts to conflict and escalating conflict, which might potentially lead to violence. Participants identified alcohol as interacting with other stressors and synergistically increased the threat or reality of physical violence. Several participants noted that existing strains in the relationship (e.g. jealousy, money) were augmented when alcohol and/or drugs were involved. This interaction between strain and alcohol/drugs is encapsulated by one participant’s narrative that draws on his own experience with violence and alcohol and drugs: “[If there were] drugs or alcohol or something [that] helps push that over the edge, cause that’s actually what part of the, it was kind of a combination of the drugs as well as the money situation” (FGD 3) which led to violence in his relationship. Another participant succinctly summed up the importance of alcohol as a catalyst for violence: “drinking … it’s hands down, it’s what starts all the shit” (FGD 4).

Jealousy and Trust

Jealousy and trust were also discussed as playing a role in provoking abuse and violent acts. Sometimes this jealousy was discussed as being the main factor contributing to intimate partner violence: “the main thing that causes violence, or, anything, is jealousy.” However, other participants also identified alcohol and drugs as interacting with this theme. One participant described how jealousy and alcohol led to a violent event when the act of going to the restroom was misinterpreted by a partner because of alcohol, which led to a confrontation and ultimately charges being pressed against one of the men. Another focus group discussion participant reported that his partner left to go talk to others at a club,

“I ended up talking to somebody, and he get mad, and confront me about it or whatever, so I said, well, why would you get mad at me? You left me with them to talk to, while you did what you had to do. And then he hit me!” (FGD 4).

While these two themes can each occur separately, the simultaneous occurrence of jealousy and alcohol/drugs was described as creating extra tension in relationships and served as a catalyst for violence.

External Violence

Though this theme was less salient, some participants also described how external experiences of homophobia could contribute to intimate partner violence in same-sex male relationships. Men discussed a strain resulting from constantly being bombarded by external anti-gay cultural messages. This source of tension, according to several participants, might generate anger and frustration among men, which in turn would lead to anger and violence within relationships:

“Violence [is] not just in your relationship, but just walking down the street. So there’s a lot of stress from work in terms of how people perceive you… so, I think because of some of those factors that may not be present in a straight relationship, that it might cause an environment of additional violence” (FGD 4).

Discussion

These findings provide insight into gay and bisexual men’s perceptions of the sources of tension in same-sex male relationships that may contribute to intimate partner violence. Even though some participants discussed personal or secondhand accounts of intimate partner violence, these findings do not necessarily highlight the actual lived experiences of men who are perpetuating or experiencing intimate partner violence in same-sex male relationships. Instead, these findings highlight how gay and bisexual men more generally perceive intimate partner violence in their communities. While some of these perceptions may accurately portray the experiences of violence in same-sex male relationships, some of these perceptions may be the result of assumptions and stereotypes. Public opinions about intimate partner violence in heterosexual relationships reveal misconceptions about perceptions of violence, including victim blaming, beliefs that a female experiencing violence can easily leave a relationship, minimising violence, and a lack of contextual and societal understanding of the problem (Gracia 2014, Yamawaki et al. 2012). Still, it is useful to understand the ways that gay and bisexual men perceive intimate partner violence among same-sex male couples because these perceptions (whether accurate or based on assumptions) can influence the experiences of those who are in violent relationships and the responses by the public.

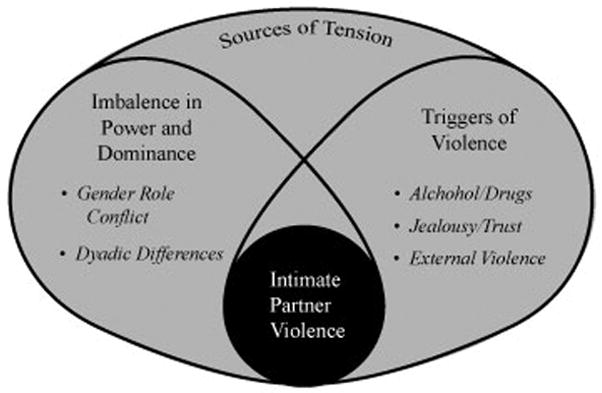

When understanding gay and bisexual men’s perceptions of intimate partner violence, it is useful to consider a lens that applies the concept of coercive control, which has typically been used to describe intimate partner violence in heterosexual relationships (Stark 2007). Many of the factors discussed by participants highlight tools that can be used to control a partner, but do not necessarily explain why intimate partner violence occurs in these relationships. For example, alcohol or jealousy may contribute to the experiences of intimate partner violence, but violence does not occur simply because a partner is drunk; violence occurs through manipulative tactics that are used to systematically control one’s partner (Stark 2007). While some participants claimed that violence occurred directly because of the source of tension, others described these sources of tension as tools that perpetrators use to manipulate their partners. Therefore, when considering the sources of tension described by participants, it is useful to conceptualise them as contributing to intimate partner violence in two ways: 1) by creating an imbalance of power and dominance between men in the relationship and 2) by triggering violence as an antecedent (Figure 1). Gender role conflict, dyadic differences in education, age, etc., and dyadic differences in outness contribute to coercive control through an imbalance of power in the relationship, while substance use, jealousy, and external violence serve as triggers to violence.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

While some of these perceived sources of tension and tools for control are similar to tools used in heterosexual relationships (e.g. alcohol and drugs, money) (Fals-Stewart 2003), many of the identified sources or tension are unique to same-sex male relationships. An important finding in this study is that men perceived gender role norms and gender role conflict as contributing to intimate partner violence in same-sex male relationships. Participants identified how stereotypes of hegemonic masculinity (Connell and Messerschmidt 2005) contribute to the trivialisation of intimate partner violence and difficulty identifying intimate partner violence in same-sex male couples; this is consistent with previous literature examining how gender role socialisation influences intimate partner violence in same-sex relationships (Brown 2008). Within the framework of hegemonic masculinity, experiencing violence contradicts the definition of masculinity, creating a barrier to the identification of violence in same-sex male relationships. However, even though stereotypes of hegemonic masculinity were recognised (identifying a perception of men as dominant), participants also identified a lack of clearly defined gender roles for men in same-sex relationships. Hegemonic masculinity is heteronormative; it defines men as dominant over women in heterosexual relationships and creates clear scripts describing masculine versus feminine roles (Connell and Messerschmidt 2005). However, this framework has still been used to understand how gender roles contribute to intimate partner violence in same-sex male relationships, identifying that some men in same-sex relationships still try to achieve a traditional form of hegemonic masculinity (Cruz 2000). This framework is consistent with the current findings as well; participants’ accounts reflected that while prescribed heteronormative gender roles may contribute to intimate partner violence in heterosexual relationships by creating an imbalance of power between genders (a concept widely examined using Power Theory) (Bell and Naugle 2008), the lack of these roles may create a different, yet equally problematic, tension within same-sex male relationships. According to participants’ views, without predetermined gender roles, men did not simply seek balance in their relationships, but rather men sought other ways to achieve hegemonic masculinity and determine dominance. Dominance was often defined by other characteristics (e.g. income, employment, age); the described characteristics are all linked to an individual’s ability to provide for the couple and the home (i.e. an older, more educated man with a higher income may more easily take on the role of being the financial provider for the household). This concept of the financial provider being the more dominant role also enforces hegemonic masculinity, which equates men’s dominance with being the head of the household (Vogler, Lyonette, and Wiggins 2008). Therefore, despite the lack of clearly defined gender roles and despite the fact that hegemonic masculinity is heteronormative (Connell and Messerschmidt 2005), men were still ascribing to this stereotypical version of masculinity, determining one dominant individual in the relationship as the “leader,” based on their ability to provide. This alternative determination of dominance based on dyadic differences was not perceived as solving the problem of unclearly defined gender roles, but rather was described as contributing to intimate partner violence. While these perceptions of intimate partner violence may not be true for all men (i.e. not all men are men are “dominant” and not all gay and bisexual men seek stereotypical gendered roles in same-sex male relationships), they still highlight that power dynamics in some same-sex male relationships can be influenced (or at least are perceived to be influenced) by a stereotypical version of hegemonic masculinity and gender roles.

The issue of power imbalances in a relationship was even more complex when men discussed dyadic differences in outness. Men in the focus group discussions described the tension that occurs when one man is out about his identity and the other is not; however, these inequalities between partners were discussed differently because it could contribute to both the in and the out partner perpetuating violence. This does not mean that participants described this tension as contributing to both partners acting as the perpetrators of violence; in fact, previous research identifies mutual violence in same-sex relationships as a myth that considers an act of self-defence as a synonymous to the perpetrator’s violence (McClennen 2005, McClennen, Summers, and Vaughan 2002). Instead, participants explained that the tension could contribute to violence on the part of either the partner who is out or the partner who is in and that the partner who is more “manipulative” and prone to perpetuating violence would be able to use this dyadic difference in outness as a “tool” for violence perpetration. Dyadic differences in outness as a possible source of tension is one that is unique to same-sex relationships and is useful to to recognise when trying to define and measure intimate partner violence among gay and bisexual men (Stephenson and Finneran 2013). Some men discussed the threats to out a partner and the controlling Behaviours requiring partners to remain closeted as acts of violence; this is consistent with the IPV-GBM, a scale to more accurately measure intimate partner violence in same-sex male relationships (Stephenson and Finneran 2013). Sources of tension resulting from asymmetries in outness illustrate how homophobic stigma and the difficulties of disclosing sexual identity can contribute to other negative health outcomes for gay and bisexual men, such as intimate partner violence.

Understanding the sources of tension that contribute to intimate partner violence in same-sex male relationships has implications for a range of health concerns. Previous research has identified a link between intimate partner violence and HIV seroconversion among gay and bisexual men (Relf 2001); this may be linked to an increase in condomless anal intercourse for men experiencing violence through a limited ability to negotiate for condom use (Buller et al. 2014). Therefore, addressing intimate partner violence and the sources of tension that contribute to intimate partner violence in same-sex male relationships may have a larger impact on men’s health, especially their sexual health.

Limitations

This study uses focus group discussions with a general population of gay and bisexual men. Since inclusion criteria did not require participants to be perpetrating or experiencing intimate partner violence, results cannot make claims about actual experiences of violence, though they do describe the perceptions of gay and bisexual men in Atlanta, GA. Though focus group discussions are often inappropriate for discussing intimate partner violence, these groups intended to understand general perceptions of intimate partner violence rather than personal experiences. Some men volunteered personal accounts of intimate partner violence, but they were not directly asked to discuss these personal stories.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, these findings still provide insight into how gay and bisexual men perceive intimate partner violence in same-sex male relationships. Additional research is needed to differentiate between which of the public perceptions presented here are accurate portrayals of lived experiences of intimate partner violence in same-sex male couples and which are based on misconceptions. This additional research combined with the findings presented here would be especially useful when building interventions. Some previous research has examined how public health interventions could address some of the sources of tension identified in this study, especially with regards to jealousy, trust and other relational stresses that occur between partners. Previous research has found that partners who report higher relationship satisfaction, experience less discordance with lifestyle choices, possess more effective problem-solving skills, practice constructive mutual communication, experience lower levels of stress, and trust each other report less intimate partner violence (Bartholomew and Cobb 2010, Hellmuth and McNulty 2008, Stephenson et al. 2011, Fonseca et al. 2006). Relational factors, such as communication, problem-solving, and trust can be addressed with dyadic interventions, such as the creation of sexual agreements between male partners (Pruitt et al. 2015). However, to prevent intimate partner violence among gay and bisexual men it is also important to focus on interventions that address the structural power imbalances that can occur in same-sex male relationships. While these types of structural interventions are being examined in heterosexual relationships (Jewkes 2002, Pronyk et al. 2006), additional research that further examines the lived experiences of intimate partner violence in same-sex male relationships is necessary to understand how the stresses of gender role conflict and the stress of living in a heteronormative society may contribute to intimate partner violence among gay and bisexual men. Interventions that address homophobic stigma and aim to redefine male gender roles in same-sex relationships as more balanced (rather than relying on dominant and submissive roles) may help to address some of the tension that contributes to intimate partner violence in same-sex male relationships.

References

- Archer John. Assessment of the Reliability of the Conflict Tactics Scales A Meta-Analytic Review. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1999;14(12):1263–1289. [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew Kim, Cobb Rebecca J. 14 Conceptualizing Relationship Violence as a Dyadic Process. Handbook of interpersonal psychology: Theory, research, assessment, and therapeutic interventions. 2010:233. AU: page span needed here. [Google Scholar]

- Bell Kathryn M, Naugle Amy E. Intimate partner violence theoretical considerations: Moving towards a contextual framework. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28(7):1096–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard Russell, Ryan Gery W. Analyzing Qualitative Data: Systematic Approaches. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Brown Carrie. Gender-role implications on same-sex intimate partner abuse. Journal of Family Violence. 2008;23(6):457–462. [Google Scholar]

- Buller Ana Maria, Devries Karen M, Howard Louise M, Bacchus Loraine J. Associations between intimate partner violence and health among men who have sex with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS medicine. 2014;11(3):e1001609. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz Kathy, Smith JA. Grounded theory. Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods. 2003:81–110. [Google Scholar]

- Coker Ann L. Does physical intimate partner violence affect sexual health? A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2007;8(2):149–177. doi: 10.1177/1524838007301162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker Ann L, Davis Keith E, Arias Ileana, Desai Sujata, Sanderson Maureen, Brandt Heather M, Smith Paige H. Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2002;23(4):260–268. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00514-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell Robert W, Messerschmidt James W. Hegemonic masculinity rethinking the concept. Gender & society. 2005;19(6):829–859. [Google Scholar]

- Craft Shonda M, Serovich Julianne M. Family-of-origin factors and partner violence in the intimate relationships of gay men who are HIV positive. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2005;20(7):777–791. doi: 10.1177/0886260505277101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz J Michael. Gay male domestic violence and the pursuit of masculinity. Gay Masculinities. 2000;12:66. Is this reference really correct? I think this is perhaps a chapter in a book. [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart William. The occurrence of partner physical aggression on days of alcohol consumption: a longitudinal diary study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(1):41. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.71.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felson Richard B, Outlaw Maureen C. The Control Motive and Marital Violence. Violence & Victims. 2007;22(4):387–407. doi: 10.1891/088667007781553964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finneran Catherine, Stephenson Rob. Intimate Partner Violence Among Men Who Have Sex With Men: A Systematic Review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2013;14(2):168–185. doi: 10.1177/1524838012470034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finneran Catherine, Stephenson Rob. Antecedents of Intimate Partner Violence Among Gay and Bisexual Men. Violence and Victims. 2014;29(3):422–435. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.vv-d-12-00140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca Carol A, Schmaling Karen B, Stoever Colby, Gutierrez Casey, Blume Arthur W, Russell Michael L. Variables associated with intimate partner violence in a deploying military sample. Military Medicine. 2006;171(7):627–631. doi: 10.7205/milmed.171.7.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gracia Enrique. Intimate partner violence against women and victim-blaming attitudes among Europeans. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2014;92(5):380–381. doi: 10.2471/BLT.13.131391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellmuth Julianne C, McNulty James K. Neuroticism, marital violence, and the moderating role of stress and behavioral skills. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;95(1):166. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.95.1.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt Stephanie, Buckley Helen, Whelan Sadhbh. The impact of exposure to domestic violence on children and young people: A review of the literature. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2008;32(8):797–810. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes Rachel. Intimate partner violence: causes and prevention. The lancet. 2002;359(9315):1423–1429. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08357-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitzinger Jenny. Qualitative research. Introducing focus groups. BMJ. 1995;311(7000):299. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7000.299. AU: page span needed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason Avonne, Blankenship Virginia. Power and affiliation motivation, stress, and abuse in intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;52(1):203. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.52.1.203. ditto. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClennen Joan C. Domestic violence between same-gender partners recent findings and future research. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2005;20(2):149–154. doi: 10.1177/0886260504268762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClennen Joan C, Summers Anne B, Vaughan Charles. Gay men’s domestic violence: Dynamics, help-seeking behaviors, and correlates. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services. 2002;14(1):23–49. [Google Scholar]

- Muhib Farzana B, Lin Lillian S, Stueve Ann, Miller Robin L, Ford Wesley L, Johnson Wayne D, Smith Philip J. A venue-based method for sampling hard-to-reach populations. Public Health Reports. 2001;116(Suppl 1):216. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.S1.216. AU: page span needed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plichta Stacey B. Intimate Partner Violence and Physical Health Consequences Policy and Practice Implications. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2004;19(11):1296–1323. doi: 10.1177/0886260504269685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pronyk Paul M, Hargreaves James R, Kim Julia C, Morison Linda A, Phetla Godfrey, Watts Charlotte, Busza Joanna, Porter John DH. Effect of a structural intervention for the prevention of intimate-partner violence and HIV in rural South Africa: a cluster randomised trial. The Lancet. 2006;368(9551):1973–1983. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69744-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruitt Kaitlyn L, White Darcy, Mitchell Jason W, Stephenson Rob. Sexual Agreements and Intimate Partner Violence among Male Couples. International Journal of Sexual Health. 2015 just-accepted 00–00. AU: is this work published now? [Google Scholar]

- Relf Michael V. Battering and HIV in men who have sex with men: A critique and synthesis of the literature. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2001;12(3):41–48. doi: 10.1016/S1055-3290(06)60143-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski Margarete. Focus on Research Methods: Whatever Happened to Qualitative Description? Reasearch in Nursing and Health. 2000;23:334–340. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4<334::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark Evan. Place of publication? Oxford University Press; 2007. Coercive Control: How men entrap women in personal life. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson Rob, Finneran Catherine. The IPV-GBM scale: a new scale to measure intimate partner violence among gay and bisexual men. PloS one. 2013;8(6):e62592. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson Rob, Rentsch Christopher, Salazar Laura F, Sullivan Patrick S. Dyadic characteristics and intimate partner violence among men who have sex with men. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2011;12(3):324. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus Murray A, Douglas Emily M. A Short Form of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scales, and Typologies for Severity and Mutuality. Violence and Victims. 2004;19(5):507–20. doi: 10.1891/vivi.19.5.507.63686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus Murray Arnold. The conflict tactics scales and its critics: An evaluation and new data on validity and reliability. In: Straus Murray Arnold, Gelles Richard J, Smith Christine., editors. Physical violence in American families: Risk factors and adaptations to violence in 8,145 families. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers; 1990. AU: page span needed. [Google Scholar]

- Tjaden Patricia, Thoennes Nancy. Prevalence and consequences of male-to-female and female-to-male intimate partner violence as measured by the National Violence Against Women Survey. Violence against Women. 2000;6(2):142–161. [Google Scholar]

- Vogler Carolyn, Lyonette Clare, Wiggins Richard D. Money, power and spending decisions in intimate relationships. The Sociological Review. 2008;56(1):117–143. [Google Scholar]

- Welles Seth L, Corbin Theodore J, Rich John A, Reed Elizabeth, Raj Anita. Intimate partner violence among men having sex with men, women, or both: early-life sexual and physical abuse as antecedents. Journal of Community Health. 2011;36(3):477–485. doi: 10.1007/s10900-010-9331-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamawaki Niwako, Ochoa-Shipp Monica, Pulsipher Craig, Harlos Andrew, Swindler Scott. Perceptions of Domestic Violence The Effects of Domestic Violence Myths, Victim’s Relationship With Her Abuser, and the Decision to Return to Her Abuser. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2012;27(16):3195–3212. doi: 10.1177/0886260512441253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun Sung Hyun. Factor Structure and Reliability of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scales’(CTS2) 10-Factor Model in a Community-Based Female Sample. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2010 doi: 10.1177/0886260510365857. AU: vol. issue no and page span missing. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]