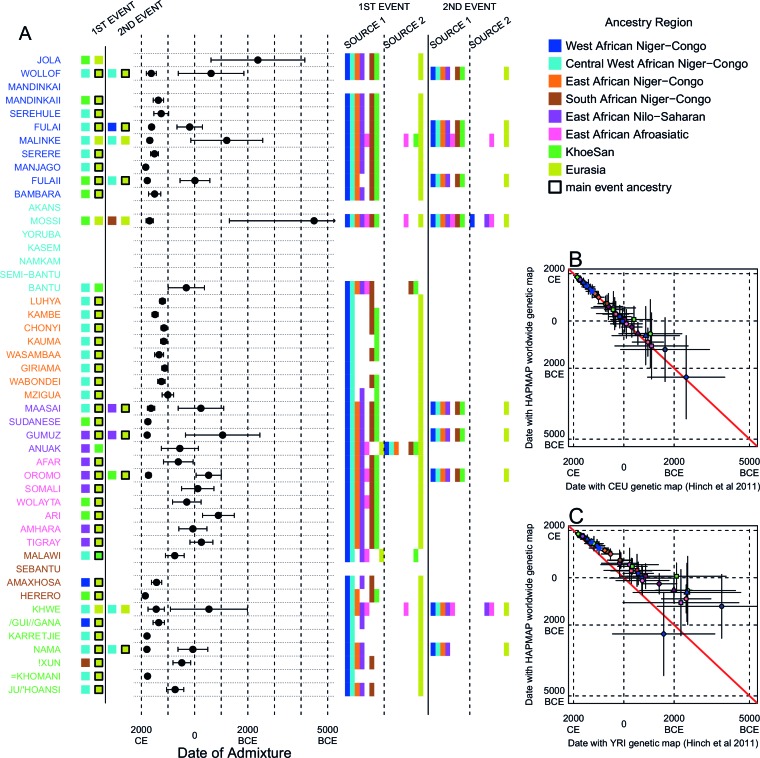

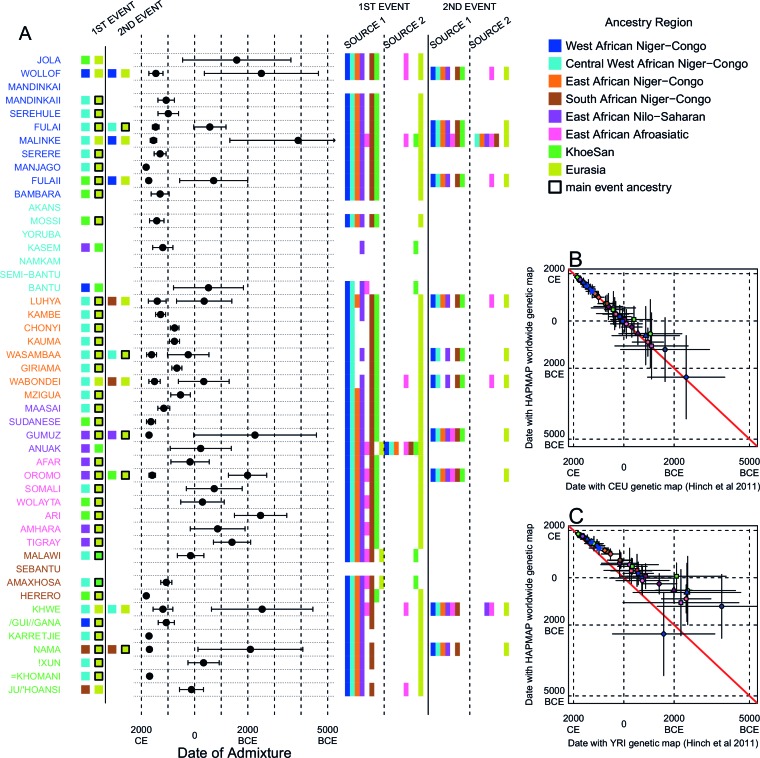

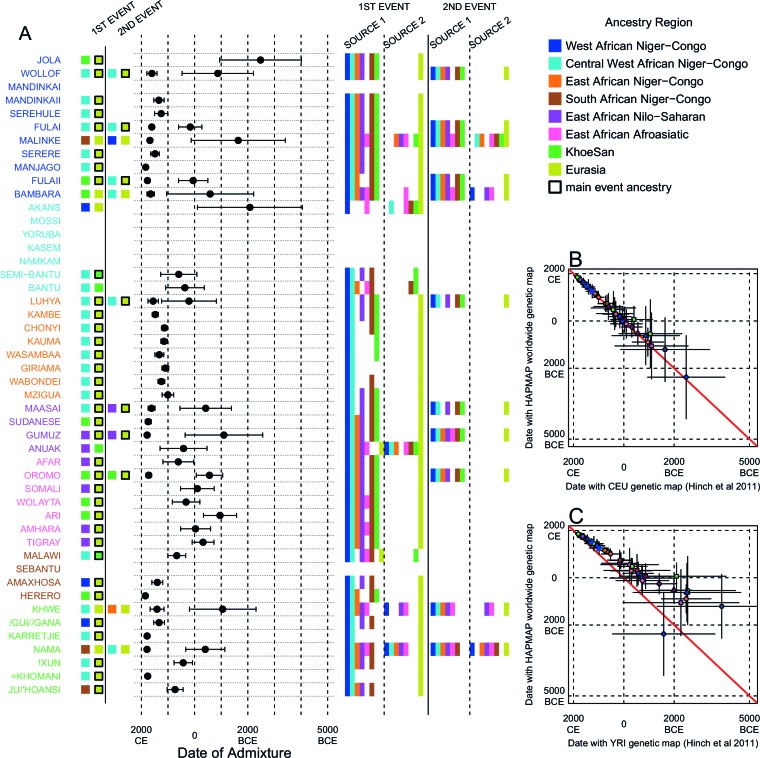

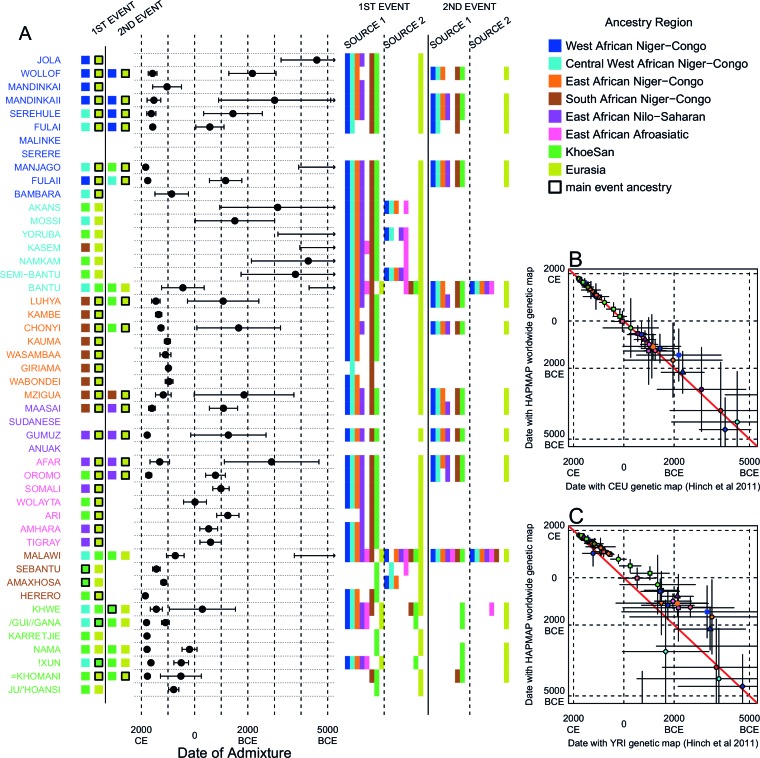

Figure 3. Inference of admixture in sub-Saharan Africa using MALDER.

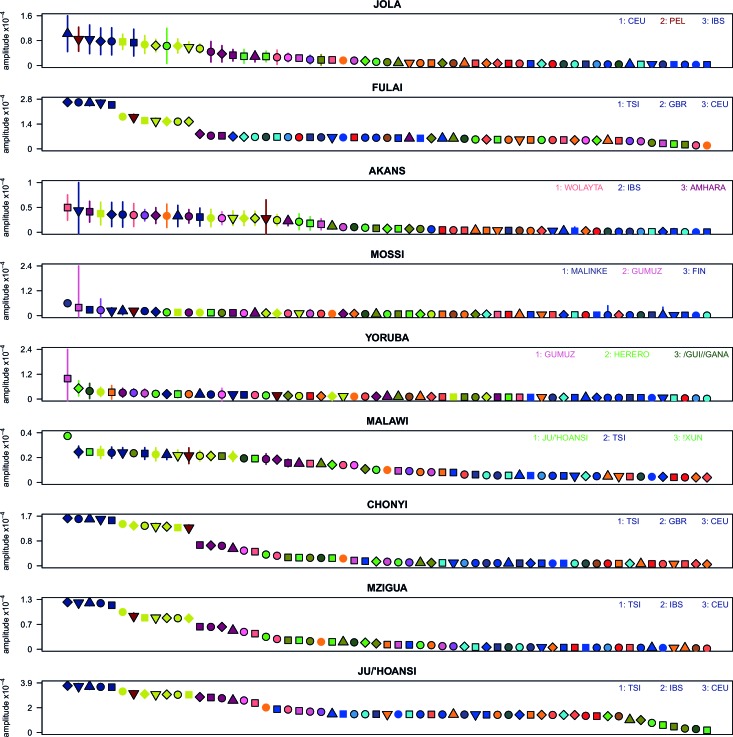

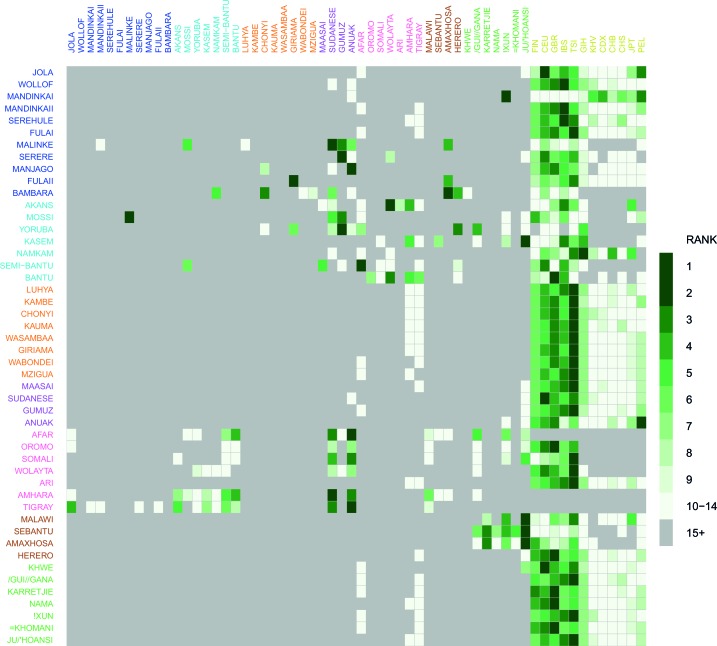

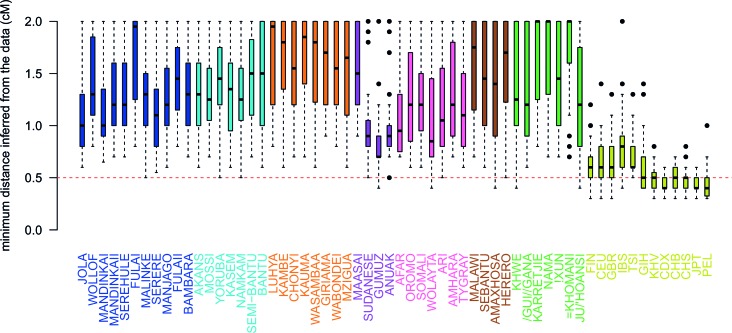

We used MALDER to identify the evidence for multiple waves of admixture in each population. (A) For each population, we show the ancestry region identity of the two populations involved in generating the MALDER curves with the greatest amplitudes (coloured blocks) for at most two events. The major contributing sources are highlighted with a black box. Populations are ordered by ancestry of the admixture sources and dates estimates which are shown 1.96 s.e. For each event we compared the MALDER curves with the greatest amplitude to other curves involving populations from different ancestry regions. In the central panel, for each source, we highlight the ancestry regions providing curves that are not significantly different from the best curves. In the Jola, for example, this analysis shows that, although the curve with the greatest amplitude is given by Khoesan (green) and Eurasian (dark yellow) populations, curves containing populations from any other African group (apart from Afroasiatic) in place of a Khoesan population are not significantly smaller than this best curve (SOURCE 1). Conversely, when comparing curves where a Eurasian population is substituted with a population from another group, all curve amplitudes are significantly smaller (). (B) Comparison of dates of admixture 1.96 s.e. for MALDER dates inferred using the HAPMAP recombination map and a recombination map inferred from European (CEU) individuals from Hinch et al. (2011). We only show comparisons for dates where the same number of events were inferred using both methods. Point symbols refer to populations and are as in Figure 1. (C) as (B) but comparison uses an African (YRI) map. Source data can be found in Figure 3—source data 1.

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7554/eLife.15266.014