Abstract

HIV disease is commonly associated with deficits in prospective memory (PM), which increase the risk of suboptimal health behaviors, like medication non-adherence. This study examined the potential benefits of a brief future visualization exercise during the encoding stage of a naturalistic PM task in 60 young adults (19–24 years) with HIV disease. Participants were administered a brief clinical neuropsychological assessment, which included a standardized performance-based measure of time- and event-based PM. All participants were also given a naturalistic PM task in which they were asked to complete a mock medication management task when the examiner showed them the Grooved Pegboard Test during their neuropsychological evaluation. Participants were randomized into: 1) a visualization condition in which they spent 30 sec imagining successfully completing the naturalistic PM task; or (2) a control condition in which they repeated the task instructions. Logistic regression analyses revealed significant interactions between clinical neurocognitive functions and visualization. HIV+ participants with intact retrospective learning and/or low time-based PM demonstrated observable gains from the visualization technique, while HIV+ participants with impaired learning and/or intact time-based PM did not evidence gains. Findings indicate that individual differences in neurocognitive ability moderate the response to visualization in HIV+ young adults. The extent to which such cognitive supports improve health-related PM outcomes (e.g., medication adherence) remains to be determined.

Keywords: Infectious disease, neuropsychological rehabilitation, episodic memory, mental imagery, AIDS dementia complex

Introduction

Individuals with HIV commonly evidence difficulties in prospective memory (PM; Carey et al., 2006). PM involves remembering to execute future actions in response to predetermined cues that are either time-based (e.g., taking medication at 5 pm) or event-based (e.g., taking medication with dinner). Although deficits in PM correlate with impairments in retrospective memory and executive functions (e.g., planning, cognitive flexibility, response inhibition) in persons with HIV (Carey et al., 2006), evidence from biomarker (Woods et al., 2006), cognitive (Gupta et al., 2010), and daily functioning (Woods et al., 2009) studies suggest that PM is a dissociable neuropsychological construct. HIV-associated PM deficits are of clinical relevance due to their independent associations with a host of real-world and health outcomes, including increased engagement in HIV transmission behaviors (Martin et al., 2007), higher rates of unemployment (Woods et al., 2011), dependence in instrumental activities of daily living (Woods et al., 2008), decreased health-related quality of life (Doyle et al., 2012), and non-adherence to healthcare regimens (Woods et al., 2009; Zogg et al., 2011). Young adults with HIV infection face the challenges of developing independence in everyday functioning (e.g., employment, managing a household) while simultaneously managing a chronic disease (e.g., medication adherence, attending medical appointments) and major psychosocial stressors (e.g., lower socioeconomic status, stigma). Thus, research that aims to enhance PM functioning in HIV disease for young adults is of both clinical and scientific interest.

In order to identify cognitive targets to improve PM functioning in HIV disease, it is important to first consider the profile of HIV-associated PM impairment. PM is a complex cognitive process in which one must encode an intention (e.g., I will take my medication after dinner) that is paired with a specific cue (e.g., leaving the dinner table). Individuals must then monitor the environment for the target cue in the face of an ongoing activity that prevents overt rehearsal (e.g., normal daily activities). After successfully detecting the cue, one must then retrieve the intended action from retrospective memory and execute it properly (Kliegel et al., 2008). Thus, PM relies heavily on several complex neurocognitive processes. Learning and attention are required to properly encode the cue-intention pairing, while retrospective memory is necessary for retention and recall of the intention. A host of different executive functions are important, as well, including planning and cognitive flexibility (e.g., while switching between monitoring and performing the ongoing task). According to the Multiprocess Theory (Einstein et al., 2005), the extent to which each of these aspects of PM places demands on the available pool of cognitive resources varies on a continuum from low (i.e., spontaneous/automatic) to high (i.e., strategic/executive). For example, time-based PM tasks require more strategic monitoring resources (i.e., independently disengaging from the ongoing task to periodically check the clock) than most event-based PM tasks, which are cued by external prompts that tend to be more salient and therefore involve more spontaneous than strategic processing.

The role of strategic monitoring demands in PM has particular significance in the context of HIV disease. Although HIV-associated neuropathologies can be observed throughout the central nervous system (Di Stefano, Sabri, & Chiodi 2005), prefrontostriatal circuits and associated executive functions appear to be particularly susceptible to HIV (Ellis, Calero & Stockin, 2009; Reger et al., 2002). Further, HIV-associated deficits in PM are moderately correlated with executive dysfunction, including cognitive flexibility (Carey et al., 2006). Thus, the profile of HIV-associated PM deficits tends to reflect dysregulation of strategic processes. For example, individuals with HIV show decrements in strategic time monitoring (i.e., clock checks) during time-based PM tasks (Doyle et al. 2013) and tend to demonstrate large effect sizes for time- versus event-based PM deficits (Martin et al. 2007; Zogg et al. 2011). Thus it may be that individuals with deficits in the strategic aspects of PM would benefit most from interventions for enhancing PM functioning.

This reliable pattern of HIV-associated PM deficits suggests that interventions designed to support strategic processing could improve PM. To this end, two prior laboratory studies from our group have found that experimental manipulations that support strategic aspects of PM cue monitoring and detection are associated with better PM accuracy in HIV+ individuals. In 2014, Loft and colleagues reported that decreasing the pace of the task environment improved accuracy on a strategically demanding (i.e., non-focal) event-based PM task in young adults with HIV infection. Another recent study found that instructions emphasizing the importance of the PM task relative to the ongoing task significantly improved accuracy on a non-focal event-based PM task in HIV+ samples with neurocognitive impairment and substance use disorders (Woods et al., 2014). In both cases, analyses of response costs to the ongoing task showed slower reaction times in the experimental versus control PM condition. Both studies support the hypothesis that these manipulations support strategic processing by shifting the allocation of cognitive resources toward PM cue monitoring and detection.

The encoding stage is another potential target for supporting strategic processing to improve PM in HIV disease. There is a long history of the beneficial effects of visualization during encoding on retrospective memory performance (e.g., Paivio 1969). Extending this tradition to PM, more recent work in seronegative samples suggests that visualization may support the role of learning in PM task performance by deepening the association between the cue and the intention at encoding and thus free up resources for cue monitoring and detection (Brewer & Marsh 2010). In this context, visualization refers to generating a mental representation of oneself encountering the PM cue, retrieving the PM task instructions, and successfully performing the PM task. Note that, visualization of this type is also known as “future-event simulation” (Leitz et al., 2009; Paraskevaides et al., 2010; Griffiths et al., 2012), “future thinking” (Leitz et al., 2009; Paraskevaides et al., 2010; Altgassen et al., 2015), or “self-imagination” (Grilli & McFarland 2011). In general, it is held that the pre-experiencing of the visuospatial context where the intended action will be retrieved deepens the encoding of the intention-cue pairing by strengthening the link between intention and broad visuospatial context (Paraskevaides et al., 2010). This hypothesis was supported by Brewer and Marsh (2010), who demonstrated that deeper encoding of the cue-to-context link by way of visualization was associated with better accuracy on event-based PM tasks. Further support for the association between brief visualization exercises utilized during the encoding stage of laboratory PM tasks and enhanced event-based PM has been shown in healthy young adults (Paraskevaides et al., 2010; McFarland & Glisky, 2012; Altgassen et al., 2015), older adults (Altgassen et al., 2015) individuals with traumatic brain injury (Potvin et al., 2011), and a mixed clinical sample with memory impairments (Grilli & McFarland, 2011). Visualization has also been associated with improvements in time-based PM in young adults (Altgassen et al., 2015), older adults (Altgassen et al., 2015), adult social drinkers (Griffiths et al., 2012), and individuals with moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury (Potvin et al., 2011). In general, the magnitude of the effects of visualization on PM accuracy across these studies is in the small-to-medium range.

Of note, visualization of PM tasks has often been employed in combination with implementation intentions. Implementation intentions are formed when the individual reads and/or repeats an intentional statement that creates an association between the intended action and the future context in which the action should be executed (i.e., upon encountering the PM cue). Intentional statements follow an “if, then” structure (e.g., “if I see X cue, then I will perform intended action Y”). Several studies report beneficial effects of brief visualization and implementation intentions during encoding for event-based PM (Chasteen et al., 2001; Schnitzpahn & Kliegal 2009; Burkard et al., 2014) and time-based PM (Schnitzpahn & Kliegal 2009) across both healthy (e.g., Meeks & Marsh, 2010) and clinical (e.g., Kardiasmenos et al., 2008) populations. To date, the literature regarding the independent and combined effects of visualization and implementation intentions suggests that the effects of these encoding interventions are not synergistic; that is, using both strategies does not necessarily improve PM performance more than using a single strategy alone (e.g., Meeks & Marsh, 2010; McFarland & Glisky, 2012; cf. McDaniel et al., 2008).

With this background in mind, the aim of the present study was to determine whether brief visualization of successful task completion (without an accompanying implementation intention) during the encoding stage of a semi-naturalistic PM task would improve PM accuracy for young adults with HIV infection. We were also interested in the extent to which individual differences in PM and supporting neurocognitive abilities would affect the response to visualization. Given the profile of HIV-associated PM deficits, we hypothesized that the effectiveness of the visualization manipulation would be more pronounced in individuals with low scores on a clinical measure of PM (i.e., the Memory for Intentions Screening Test; Raskin et al., 2010). Given that PM requires cognitive processes supported by other cognitive domains, particularly learning, delayed memory, and executive functions, the present study also sought to investigate whether impairments in these cognitive domains would also moderate the benefits of visualization. We hypothesized that individuals with deficits in these domains would benefit more from visualization than individuals with intact cognition. In other words, individuals with deficits in the higher-order neurocognitive functions that support naturalistic PM would be at highest risk for PM failures in the absence of encoding supports. Thus, the visualization encoding exercise was hypothesized to provide a critical compensatory buffer function for participants with deficits who would therefore need of such neurocognitive support; on the other hand, it was expected that visualization would serve as a more modest neurocognitive booster for individuals with already strong abilities in the critical underlying neurocognitive capacities that support naturalistic PM.

Method

Participants

Approval for this study was provided by the human research protections programs at the University of California, San Diego and Wayne State University. The eligible sample was comprised of 60 young adults (age range: 19 – 24 years) with HIV infection recruited from urban HIV clinics in Detroit (n = 30) and San Diego (n = 30). The sample was comprised of the same cohort of participants as described by Loft and colleagues (2014), and Woods and colleagues (2014); however, the visualization and MIST data have not heretofore been published. Inclusion criteria for the sample were diagnosis of HIV infection (confirmed by medical record) and the ability to provide consent on the day of study evaluation. Participants with potential psychotic disorders or neurological conditions known to negatively affect cognition (e.g., seizure disorder, traumatic brain injury with loss of consciousness greater than 15 minutes) were excluded. All participants were randomized into either a visualization (n=30) or control (n=30) condition. Demographics and clinical variables of the study cohort are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Study Participants by Condition

| Characteristic | VIS (N=30) | CNL (N=30) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Site (UCSD/WSU) | 15/15 | 15/15 | 1.000 |

| Age (years) | 22.6 (1.5) | 22.6 (1.1) | 1.000 |

| Education (years) | 11.8 (1.4) | 12.3 (1.2) | 0.124 |

| Estimated verbal IQ (WTAR reading) | 89.4 (15.8) | 90.2 (12.4) | 0.821 |

| Sex (% male) | 83.3 | 90.0 | 0.448 |

| Ethnicity (%) | |||

| Caucasian | 23.3 | 3.3 | |

| African-American | 50.0 | 60.0 | |

| Hispanic | 26.7 | 33.3 | |

| Other | 0.0 | 3.3 | |

| Global Severity Indexa | 60.4 (12.7) | 54.5 (10.2) | 0.049 |

| Somatization | 59.6 (10.3) | 52.8 (12.5) | 0.025 |

| Depression | 59.6 (12.4) | 53.5 (10.9) | 0.046 |

| Anxiety | 57.5 (13.1) | 52.8 (10.9) | 0.138 |

| Problematic Substance Use (%)b | |||

| Alcohol | 26.7 | 33.3 | 0.573 |

| Non-Alcohol | 60.0 | 56.7 | 0.793 |

| HIV Disease | |||

| Estimated duration of infection (mos.)c | 31 (24, 39) | 46 (28, 64) | 0.125 |

| Nadir CD4 T-cell count (cells/μl)d | 337 (272, 402) | 343 (266, 419) | 0.907 |

| Current CD4 T-cell count (cells/μl) | 501 (429, 575) | 585 (478, 692) | 0.194 |

| AIDS status (%)e | 14.3 | 23.3 | 0.380 |

| Plasma HIV RNA (% detectable) | 60.0 | 56.7 | 0.793 |

| ART Use (% ON) | 73.3 | 76.7 | 0.766 |

| HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder (%) | 76.7 | 73.3 | 0.766 |

| Medication Management Total | 11.2 (3.8) | 11.1 (3.2) | 0.971 |

| Time-Based PM (% Lowf) | 36.7 | 20.0 | |

| Event-Based PM (% Lowf) | 30.0 | 16.7 | |

| Learning (% Lowg) | 56.7 | 50.0 | |

| Delayed Memory (% Lowg) | 66.7 | 63.3 | |

| Executive Functions (% Lowg) | 30.0 | 40.0 | |

Note.

Based on the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI; Derogatis, 1993).

Based on the Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Use Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST v. 3.0).

N=29 for CTL.

N=29 for VIS.

N=28 for VIS.

Based on sample median split.

T<40.

Data are presented as means and standard deviations or 95% confidence intervals except where indicated. ART = Antiretroviral therapy. WTAR = Wechsler Test of Adult Reading.

Materials and Procedure

After providing written informed consent, participants were administered a semi-structured clinical interview to obtain relevant clinicodemographic information, a brief neurocognitive battery, and a series of questionnaires to assess mood and cognitive complaints (see below). HIV disease and treatment variables were extracted from clinic medical records.

Visualization PM Experiment

All participants were administered a semi-naturalistic, event-based PM task that was embedded in the brief clinical neuropsychological assessment, which served as the ongoing task. At the beginning of the evaluation, participants were prescribed the intention to tell the examiner it was time to perform the Medication Management Test, Revised (MMT-R; Scott et al., 2011) when they were presented with the grooved pegboard task (i.e., the cue) during the neuropsychological assessment. Participants were shown the grooved pegboard stimulus while receiving task instructions. The grooved pegboard was later presented as part of the standard protocol for the neuropsychological assessment approximately one hour after the PM instructions were delivered. Participants were not given a time frame in which to expect presentation of the grooved pegboard. In the interim, they were engaged in completing the standard neurocognitive tests detailed below. The MMT-R required participants to dispense the correct dosages of different mock medications and answer questions based on the directions provided. Participants in the control condition were asked to repeat the instructions back to the examiner. Participants in the visualization group were instructed to repeat instructions, and also to spend 30 seconds imagining themselves seeing the grooved pegboard and successfully completing the PM task. Participants who did not repeat PM task instructions correctly the first time were corrected by the examiner and prompted to repeat the instructions a second time. Participant errors made during the second repetition were rare and were not corrected. Participants in the visualization group were not instructed to describe their visualizations out loud. These instructions are consistent with the experimental approach previously utilized by Brewer et al. (2011). PM task performance was binary; participants either met criteria for intact PM recall (Complete) by initiating the MMT-R following presentation of the correct event cue (the grooved pegboard stimulus), and before they began the grooved pegboard task, or they did not meet criteria (Incomplete) for any reason.

Prospective Memory Ability

All participants completed the research version of the Memory for Intentions Screening Test (MIST; Raskin, 2004; Woods et al., 2008), which is a standardized performance-based measure developed to assess both time-based (TB) and event-based (EB) prospective memory. Total scores for these subscales range from 0 to 8. Participants perform four time-based and four event-based PM tasks over a 30-minute period, during which they are engaged in a word-search puzzle (the ongoing distractor task). The PM tasks are balanced across delay interval (i,e., either a 2-min or 15-min delay) and response modality (i.e., either verbal or physical response). Participant scores on the TB and EB subscales were dichotomized into Low and High categories using a sample-based median split that also generally corresponded to 1 SD below the mean of a sample of healthy younger adults from a previously published study (Woods et al., 2008).

Neuropsychological Assessment

Participants completed a relatively brief neurocognitive battery designed to measure the essential domains recommended by the Frascati group (Antinori et al., 2007) for diagnosis of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND). The following five domains and associated measures were assessed in the current study: (1) Learning: Hopkins Verbal Learning Test – Revised Trials 1–3 (HVLT-R; Brandt & Benedict 2001) and the Brief Visuospatial Memory Test –Revised Trials 1–3 (BVMT-R; Benedict 1997); (2) Retrospective memory: HVLT-R and BVMT-R Delay Trials; (3) Executive functions: Tower of London – Drexel Version total moves (Culbertson & Zillmer, 2001), Trail Making Test, Part B total time (Army Individual Test Battery, 1994; Heaton, Miller, Taylor, & Grant, 2004), and the Color Word Interference Test interference trial from the Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System (DKEFS; Delis, Kaplan, & Kramer, 2001); (4) Information processing speed: Trail Making Test, Part A total time (Heaton et al., 2004), Tower of London total execution time, Color Word Interference Test color trial, Symbol Digit Modalities Test total correct (SDMT; Smith, 1982); and (5) Motor skills: dominant and non-dominant total time on the Grooved Pegboard Test (Heaton et al., 2004; Klove, 1963). Participants were also administered the Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (WTAR; Psychological Corporation, 2001) to estimate verbal IQ. All measures were administered by trained research assistants and scored in accordance with published manuals. Raw scores were converted to T-scores adjusted for age, education, gender, and/or ethnicity, based on the best available normative standards (references above). T-scores were then averaged to create composite scores for each cognitive domain, and were then dichotomized into High and Low categories, with the Low category comprised of scores that fell below published demographically-adjusted normative standards (≥1 SD below the mean).

Neuropsychiatric Measures

Participants were also administered a brief neuropsychiatric assessment, which included the Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST; World Health Organization, 2002) and the Brief Symptom Inventory - 18 (BSI-18; Derogatis, 1993). The ASSIST is a relatively brief screening measure comprised of eight questions that covers frequency of use and associated problems for each of ten substances: tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, amphetamine-type stimulants, cocaine, sedatives, opiates, inhalants, hallucinogens, and ‘other drugs.’ The BSI-18 is another brief self-report measure, comprised of 18 items that assess general psychological distress (Meijer, de Vries & van Bruggen, 2011). The BSI-18 provides a Global Severity Index score, as well as three subscale scores (i.e., somatization, depression, and anxiety).

Data Analysis

In order to determine the benefit of the visualization technique for naturalistic PM at differing levels of neurocognitive abilities, we conducted a series of five logistic regressions with naturalistic PM (complete vs. incomplete) as the criterion. Predictors included the experimental condition (i.e., visualization vs. control), clinical cognitive domain impairment (i.e. time- and event-based MIST, learning, memory, and executive functions), and their interactions. Despite the randomization procedure, the study groups differed significantly on race/ethnicity, self-reported depression and somatization, and on performance-based measures of executive functions. In order to determine whether such group differences should be included as covariates in our statistical models, we evaluated their associations with semi-naturalistic PM accuracy in the entire study sample. Only those variables with significant associations were selected for inclusion as covariates in the models. Depression, somatization, and level of executive functions were not found to be significantly associated with semi-naturalistic PM performance (p > 0.05). Only race/ethnicity demonstrated a significant association with semi-naturalistic PM performance and was included as a covariate in all models. For all analyses, the critical α level was set to 0.05.

Results

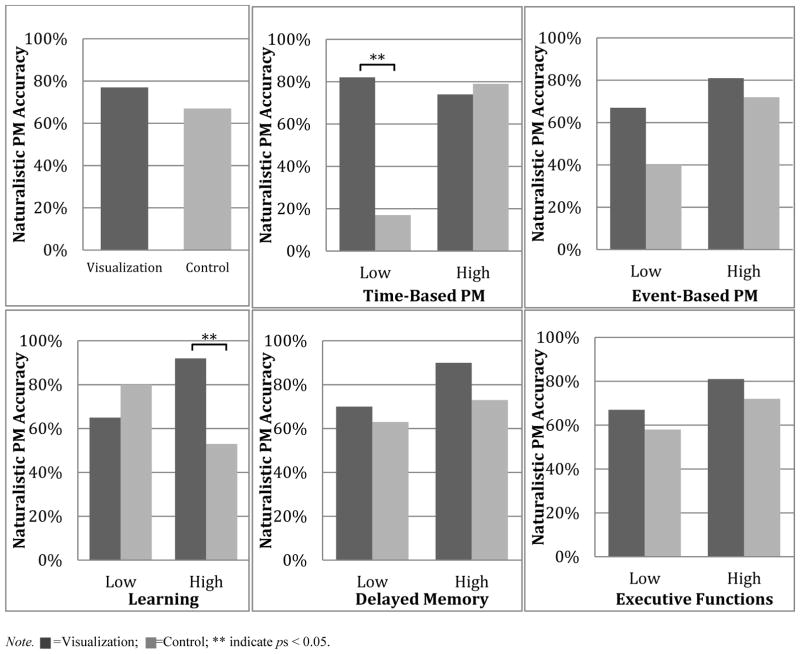

Visualization and Clinical PM (MIST)

An overall effect of visualization on PM performance was not observed (χ2= 0.742, p= 0.389). However, the overall MIST time-based PM logistic regression model was significant (χ2=14.71, p=0.005). A significant interaction emerged between condition and time-based PM (χ2=7.27, p=0.007), such that for participants with low time-based PM scores, completing the visualization condition was associated with significantly higher rates of semi-naturalistic PM accuracy than the control condition (81.8% vs. 16.7% success; χ2=7.20, p=0.007, OR=22.5, confidence interval [CI]=1.6–314.6). In contrast, there was no effect of condition for participants with high time-based PM scores (73.7% vs. 79.2% success; χ2=0.18, p=0.673, OR=0.737, [CI]=0.2–3.0). No main effects of condition (χ2=2.24, p=0.134) or time-based PM (χ2=1.70, p=0.192) were observed. When included as a covariate in the time-based PM model, level of executive functions was not a significant contributor (p= 0.989) and did not affect the significance of the interaction between condition and time-based PM (p=0.009). The overall event-based PM model was not significant (χ2=9.40, p=0.052), with no main effects of condition (χ2=1.26, p=0.262) or event-based PM score (χ2=2.91, p=0.088) observed. The interaction between condition and event-based PM score was also non-significant (χ2=1.05, p=0.305).

Visualization and Clinical Neurocognitive Impairment

The overall logistic regression model for learning was significant (χ2=10.0, p=0.039). A significant interaction emerged between condition and learning (χ2=4.08, p=0.043); contrary to expectations, post-hoc pairwise comparisons revealed that among participants with high learning scores, those in the visualization condition demonstrated a significantly higher rate of semi-naturalistic PM completion than those in the control condition (92.3% vs. 53.3% success; χ2=5.72, p=0.0167, OR=10.5, [CI]=1.1–102.3). In contrast, there was no effect of condition for participants with impaired learning scores (64.7% vs. 80.0% success; χ2=0.94, p=0.333, OR=0.46, [CI]=0.09–2.29). No main effects of condition (χ2=0.42, p=0.517) or learning (χ2=0.07, p=0.794) were observed. Non-significant findings were observed for the overall models examining delayed memory (χ2=7.10, p=0.131) and executive functions (χ2=6.42, p=0.169).

Discussion

The profile of HIV-associated PM impairment is often characterized by decrements in strategic processes (e.g., Doyle et al., 2013), which are associated with greater risk of worse real-world problems, including non-adherence to cART regimens (Woods et al., 2009). The present study examined the potential benefits of a brief future visualization exercise during the encoding stage of a semi-naturalistic event-based PM task for young adults with HIV disease. Our data show that visualization of future intentions at encoding was not universally effective in our cohort. However, visualization was beneficial for naturalistic PM performance specifically among seropositive individuals with low time-based PM and/or intact learning. The benefit of visualization on event-based PM observed among this subset of young HIV+ individuals is consistent with prior studies in healthy young adults (Paraskevaides et al., 2010; McFarland & Glisky, 2012), older adults (Altgassen et al., 2015), and clinical samples (Grilli & McFarland, 2011; Potvin et al., 2011). Additionally, these data provide further evidence that inclusion of implementation intentions is not required for visualization to bolster event-based PM (Meeks & Marsh, 2010; McFarland & Glisky, 2012). The current findings regarding the benefits of bolstering strategic processes during the encoding stage of PM also complement prior studies showing that supporting monitoring (Woods et al., 2014) and cue detection (Loft et al., 2014) can enhance PM accuracy on laboratory measures of PM in HIV+ samples. Finally, the finding that individual differences in clinical PM and learning appear to influence the response to visualization at encoding is a particularly novel one. These differential effects of visualization on PM were large and independent of clinicodemographic factors, including education, neuropsychiatric comorbidity, and HIV disease severity, all of which were either comparable across experimental groups or covaried in the statistical models.

Of both conceptual and clinical relevance, visualizing future intentions at encoding afforded the greatest improvements in naturalistic PM accuracy for HIV+ participants with poor strategic PM ability as measured by the time-based scale of the MIST. In other words, when participants with low time-based PM performance were instructed at encoding to visualize themselves successfully detecting the cue and executing the PM intention, their naturalistic PM accuracy was no different than that of participants with high time-based PM scores. The magnitude of the visualization effect among persons with low time-based PM performance was considerable, with a greater than 20 fold increased odds of successfully completing the naturalistic PM task among these participants. The specificity of this differential response across levels of strategic PM was supported by the absence of an association between visualization and the event-based PM scale of the MIST, which measures the more automatic aspects of PM. Conceptually, these data suggest that visualization may improve naturalistic PM for HIV+ young adults with deficient strategic resources by strengthening the encoding of the cue-intention pairing, which in turn increases the likelihood that the cue-intention pairing is properly consolidated into delayed memory and readily retrieved upon detection of the cue. A second, not necessarily mutually exclusive, possibility is that visualization at encoding has indirect effects on PM monitoring by reducing cognitive load during the delay interval and/or enhancing the level of activation of the cue-intention pairing, which would ultimately enhance cue detection. Future experimental work in which the relatively automatic versus strategic demands of the cue-intention pairing (e.g., semantic relatedness), delay interval, and cue salience are manipulated in the context of future visualization are needed to more carefully examine these possibilities.

One curious finding was that participants with higher levels of time-based PM did not benefit from visualization. While the benefit of visualization was hypothesized to be greater for participants with low time-based PM scores, at least some modest benefit of visualization for participants with intact time-based PM was still expected. Prior studies indicate that visualization improves time-based PM performance for groups who are unlikely to demonstrate notable time-based PM deficits (e.g., adult social drinkers; Griffiths et al., 2012). Nevertheless, these earlier studies did not stratify participants on the basis of clinical PM performance, so it is difficult to determine if a similar differential effect of visualization may have been observed. It is also possible that there were ceiling effects on the naturalistic PM task. However, participants with high time-based PM accuracy demonstrated only about 80 percent accuracy on the naturalistic PM task irrespective of condition, suggesting that ceiling effects are unlikely. Another possibility is that this very brief visualization exercise was not sufficiently powerful (e.g., too brief) to improve PM accuracy for individuals with already strong PM ability.

Another unexpected finding from this study was that HIV+ young adults with intact learning benefited from visualizing future intentions at encoding, but persons with impaired learning scores did not. Although the magnitude of the visualization effect among these participants was approximately half that which was observed for participants with low time-based PM, it was still quite formidable; specifically, visualization was associated with greater than 10 fold odds of successfully completing the naturalistic PM task among HIV+ participants with intact versus impaired learning. Intuitively, one might expect that visualizing oneself successfully detecting the cue and retrieving the intention would differentially improve PM accuracy for participants with lower learning scores by virtue of supporting an impaired neurocognitive function (i.e., facilitating deeper encoding). However, these findings suggest that intact retrospective learning/encoding appears to be necessary for visualization of future intentions to enhance PM accuracy in HIV+ young adults. This finding provides some further support for the direct-action interpretation of the benefits of visualization at PM encoding as detailed above. Once again, the specificity of these retrospective learning effects is supported by the absence of significant moderating effects of delayed memory and executive functions on the association between visualization and naturalistic PM memory. This finding also illuminates the importance of exploring other interventions that support PM for individuals with poorer learning.

Collectively, the current results most strongly support a direct effect of visualization on encoding to improve naturalistic PM performance among persons with low PM capacity and intact learning. Such effects could be due to a few possible cognitive factors. First, visualization could be deepening encoding by acting as an elaboration strategy. In contrast to maintenance rehearsal, where information processing remains at the level of rote repetition, elaborative rehearsal is thought to deepen encoding further by linking the information to be recalled with other material in memory, both between and beyond the specific information being learned (Craik & Lockhart, 1972). Similarly, imagining oneself performing the intended action in the future visuospatial context could create links between and beyond the information being learned (e.g., between the cue –intention pairing and the future context). In support of this interpretation is the finding that individuals with intact learning, which would be required to establish such associations, showed disproportionate benefit from visualization. Another, not necessarily mutually exclusive, possibility is that visualization deepens encoding by increasing the self-referential context of the information (e.g., Klein, Loftus, & Kihlstrom, 1996). In this way, the act of visualizing oneself performing a future action in response to a cue is thought to deepen encoding by anchoring the cue, intention, and imagined visuospatial environment in a self-referential context. Indeed, Grilli and Glisky (2010) observed that imagining a future event from a personal perspective improved recognition memory to a greater degree than semantic elaboration. Future studies will be necessary to investigate the relative influence of these different mechanisms on the positive effects of visualization for naturalistic PM.

A few limitations of the study warrant discussion. First, the grooved pegboard cue was focal to the ongoing task and the retrospective memory load was low (i.e., only one intention to recall), which resulted in a very high rate of intact cue-intention pairing. In other words, very few participants detected the cue without also recalling the correct intention, irrespective of visualization encoding condition. Consequently, the selected PM task precluded the possibility that any evidence that visualizing future intentions improved cue-detection pairing (e.g., successfully recall that a task needs to be completed, but identify wrong task) could arise from the data. Future studies incorporating manipulations of delayed memory load would provide more illuminative data in this respect. The study design also lacked a comparison group of healthy, seronegative adults, precluding the opportunity to examine how HIV status moderates the effects of visualization at encoding on PM accuracy. Additionally, the characteristics of the study sample were limited primarily to young men; as such, the extent to which these findings are relevant to other aspects of the HIV populations (e.g., women, older adults) remain to be determined. Finally, it would have been valuable to include measures of other domains of interest. For example, are individuals with impaired spatial cognition less likely to benefit from a visualization exercise? Inclusion of a spatial cognition measure may have addressed this possibility. Similarly, are individuals who produce highly vivid visualizations more likely to benefit from visualization than individuals who do not? Measures of vividness or strength of visualizations may have been useful to include as well, though the few studies that have included measures of vividness have failed to observe meaningful differences of vividness ratings between groups with significantly different levels of PM performance (Leitz et al., 2009; Griffiths et al., 2012; Altgassen et al., 2015).

In summary, these data show that individual differences in neurocognitive ability moderate the response to visualization in HIV+ young adults. Visualization interventions such as this have great practical utility, given that they are brief, can be administered with simple instructions, and do not require any physical materials. Future studies may wish to compare the relative potential benefits of other strategies for supporting PM encoding, particularly implementation intention (McFarland & Glisky, 2012) and self-generation (McDaniel & Scullin, 2010), either in isolation or in combination with visualization. Similarly, given that manipulations targeting the monitoring and cue detection stages of PM have been shown to improve PM accuracy in HIV+ young adults (e.g., Loft et al., 2014), it would also be worth determining the potential benefits of approaches that support strategic processing across the spectrum of PM. For example, does supporting encoding increase response to interventions that support monitoring and cue detection? Furthermore, future work is needed to apply these approaches to enhancing PM to real-world scenarios relevant to persons living with HIV disease, such as household activities (e.g., timely bill paying) and health behaviors (e.g., medical appointment attendance).

Figure 1.

Effects of Condition, Clinical Prospective Memory (PM) and Neurocognitive Impairment on Naturalistic PM Completion

Note. =Visualization; =Control; ** indicate ps < 0.05.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH grants R01DA034497 (SNK, SPW), R01MH073419 (SPW), and T32DA31098 (SPW).

References

- Altgassen M, Rendell PG, Bernhard A, Henry JD, Bailey PE, Phillips LH, Kliegel M. Future thinking improves prospective memory performance and plan enactment in older adults. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2015;68:192–204. doi: 10.1080/17470218.2014.956127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antinori A, Arendt G, Becker JT, Brew BJ, Byrd DA, Cherner M, … Wojna VE. Updated research nosology for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Neurology. 2007;69:1789–1799. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000287431.88658.8b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Army Individual Test Battery. Manual of directions and scoring. Washington, D.C: War Department, Adjutant General’s Office; 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Benedict RHB. Brief Visuospatial Memory Test-Revised. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt J, Benedict RHB. Hopkins Verbal Learning Test—Revised. Professional manual. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer GA, Marsh RL. On the role of episodic future simulation in encoding of prospective memories. Cognitive Neuroscience. 2010;1:81–88. doi: 10.1080/17588920903373960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer GA, Knight J, Meeks JT, Marsh RL. On the role of imagery in event-based prospective memory. Consciousness and Cognition. 2011;20:901–907. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2011.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkard C, Rochat L, Emmenegger J, Juillerat Van der Linden AC, Gold G, Van der Linden M. Implementation intentions improve prospective memory and inhibition performances in older adults: the role of visualization. Applied Cognitive Psychology. 2014;28:640–652. [Google Scholar]

- Carey CL, Woods SP, Rippeth JD, Heaton RK, Grant I The HNRC Group. Prospective memory in HIV-1 infection. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2006;28:536–548. doi: 10.1080/13803390590949494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chasteen AL, Park DC, Schwarz N. Implementation intentions and facilitation of prospective memory. Psychological Science. 2001;12:457–461. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craik FIM, Lockhart RS. Levels of processing: a framework for memory research. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior. 1972;11:671–684. [Google Scholar]

- Culbertson WC, Zillmer EA. The Tower of London DX (TOL-DX) manual. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Delis D, Kaplan EB, Kramer J. The Delis–Kaplan Executive Function System. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR. The Brief Symptom Inventory. Pearson; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Di Stefano M, Sabri F, Chiodi F. HIV-1 structural and regulatory proteins and neurotoxicity. The Neurology of AIDS. 2005;2:49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle K, Weber E, Atkinson JH, Grant I, Woods SP HIV Neurobehavioral Research Program (HNRP) Group. Aging, prospective memory, and health-related quality of life in HIV infection. AIDS and Behavior. 2012;16:2309–2318. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0121-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle K, Loft S, Morgan EE, Weber E, Cushman C, Johnston E … The HNRP Group. Prospective memory in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND): The neuropsychological dynamics of time monitoring. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2013;35:359–372. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2013.776010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einstein GO, McDaniel MA. Prospective memory: Multiple retrieval processes. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2005;14:286–290. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis RJ, Calero P, Stockin MD. HIV infection and the central nervous system: a primer. Neuropsychological Review. 2009;19:144–151. doi: 10.1007/s11065-009-9094-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths A, Hill R, Morgan C, Rendell PG, Karimi K, Wanagaratne S, Curran HV. Prospective memory and future event simulation in individuals with alcohol dependence. Addiction. 2012;107:1809–1816. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilli MD, Glisky EL. Self-imagining enhances recognition memory in memory-impaired individuals with neurological damage. Neuropsychology. 2010;24:698–710. doi: 10.1037/a0020318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilli MD, McFarland CP. Imagine that: self-imagination improves prospective memory in memory-impaired individuals with neurological damage. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. 2011;21:847–859. doi: 10.1080/09602011.2011.627263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S, Paul Woods S, Weber E, Dawson MS, Grant I HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center (HNRC) Group. Is prospective memory a dissociable cognitive function in HIV infection? Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2010;32:898–908. doi: 10.1080/13803391003596470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Miller SW, Taylor MJ, Grant I. Revised comprehensive norms for an expanded Halstead-Reitan Battery: Demographically adjusted neuropsychological norms for African American and Caucasian adults. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kardiasmenos KS, Clawson DM, Wilken JA, Wallin MT. Prospective memory and the efficacy of a memory strategy in multiple sclerosis. Neuropsychology. 2008;22:746–754. doi: 10.1037/a0013211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein SB, Cosmides L, Costabile KA, Mei L. Is there something special about the self? A neuropsychological case study. Journal of Research in Personality. 2002;36:490–506. [Google Scholar]

- Klein SB, Loftus J, Kihlstrom JF. Self-knowledge of an amnesic patient: toward a neuropsychology of personality and social psychology. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1996;125:250–260. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.125.3.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliegel M, Jäger T, Phillips LH. Adult age differences in event-based prospective memory: A meta-analysis on the role of focal versus non-focal cues. Psychology and Aging. 2008;23:203–208. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.23.1.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kløve H. Clinical neuropsychology. In: Forster FM, editor. The Medical Clinics of North America. New York: Saunders; 1963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loft S, Doyle KL, Naar-King S, Outlaw AY, Nichols SL, Weber E, … Woods SP. Allowing brief delays in responding improves event-based prospective memory for young adults living with HIV disease. Journal of clinical and experimental neuropsychology. 2014;36:761–772. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2014.942255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin EM, Nixon H, Pitrack DL, Weddington W, Rains NA, Nunnally G, … Bechara A. Characteristics of prospective memory deficits in HIV-seropositive substance-dependent individuals: Preliminary observations. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2007;29:496–504. doi: 10.1080/13803390600800970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel MA, Howard DC, Butler KM. Implementation intentions facilitate prospective memory under high attention demands. Memory & Cognition. 2008;36:716–724. doi: 10.3758/mc.36.4.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel MA, Scullin MK. Implementation intention encoding does not automatize prospective memory responding. Memory & Cognition. 2010;38:221–232. doi: 10.3758/MC.38.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland C, Glisky E. Implementation intentions and imagery: Individual and combined effects on prospective memory among young adults. Memory & Cognition. 2012;40:62–69. doi: 10.3758/s13421-011-0126-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeks JT, Marsh RL. Implementation intentions about nonfocal event-based prospective memory tasks. Psychological Research. 2010;74:82–89. doi: 10.1007/s00426-008-0223-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijer RR, de Vries RM, van Bruggen V. An evaluation of the Brief Symptom Inventory–18 using item response theory: Which items are most strongly related to psychological distress? Psychological Assessment. 2011;23:193–202. doi: 10.1037/a0021292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paivio A. Mental imagery in associative learning and memory. Psychological Review. 1969;76:241–263. [Google Scholar]

- Paraskevaides T, Morgan CJ, Leitz JR, Bisby JA, Rendell PG, Curran HV. Drinking and future thinking: acute effects of alcohol on prospective memory and future simulation. Psychopharmacology. 2010;208:301–308. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1731-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potvin MJ, Rouleau I, Sénéchal G, Giguère JF. Prospective memory rehabilitation based on visual imagery techniques. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. 2011;21:899–924. doi: 10.1080/09602011.2011.630882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psychological Corporation. Wechsler Test of Adult Reading. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Raskin S. Memory for intentions screening test [abstract] Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2004;10(Suppl 1):110. [Google Scholar]

- Raskin S, Buckheit C, Sherrod C. MIST Memory for Intentions Test professional manual. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Reger M, Welsh R, Razani J, Martin DJ, Boone KB. A meta-analysis of the neuropsychological sequelae of HIV infection. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2002;8:410–424. doi: 10.1017/s1355617702813212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnitzspahn KM, Kliegel M. Age effects in prospective memory performance within older adults: the paradoxical impact of implementation intentions. European Journal of Ageing. 2009;6:147–155. doi: 10.1007/s10433-009-0116-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JC, Woods SP, Vigil O, Heaton RK, Schweinsburg BC, Ellis RJ, Grant I, Marcotte TD San Diego HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center (HNRC) Group. A neuropsychological investigation of multitasking in HIV infection: implications for everyday functioning. Neuropsychology. 2011;25:511–519. doi: 10.1037/a0022491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. Symbol Digit Modalities Test manual. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- WHO ASSIST Working Group. The Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST): development, reliability and feasibility. Addiction. 2002;97:1183–1194. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods SP, Morgan EE, Marquie-Beck J, Carey CL, Grant I, Letendre SL. Markers of macrophage activation and axonal injury are associated with prospective memory in HIV-1 disease. Cognitive and behavioral neurology: official journal of the Society for Behavioral and Cognitive Neurology. 2006;19:217–221. doi: 10.1097/01.wnn.0000213916.10514.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods SP, Dawson MS, Weber E, Gibson S, Grant I, Atkinson JH The HNRC Group. Timing is everything: Antiretroviral non-adherence is associated with impairment in time-based prospective memory. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2009;15:42–52. doi: 10.1017/S1355617708090012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods SP, Iudicello JE, Moran LM, Carey CL, Dawson MS, Grant I The HNRC Group. HIV-associated prospective memory impairment increases risk of dependence in everyday functioning. Neuropsychology. 2008;22:110–107. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.22.1.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods SP, Weber E, Weisz B, Twamley EW, Grant I the HNRP Group. Prospective memory deficits are associated with unemployment in persons living with HIV infection. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2011;56:77–84. doi: 10.1037/a0022753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods SP, Doyle KL, Morgan EE, Naar-King S, Outlaw AY, Nichols SL, Loft S. Task importance affects event-based prospective memory performance in adults with HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders and HIV-infected young adults with problematic substance use. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2014;20:652–662. doi: 10.1017/S1355617714000435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zogg JB, Woods SP, Weber E, Doyle K, Grant I The HNRP Group. Are time- and event-based prospective memory comparably affected in HIV infection? Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2011;26:250–259. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acr020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]