ABSTRACT

Size and shape are important aspects of nuclear structure. While normal cells maintain nuclear size within a defined range, altered nuclear size and shape are associated with a variety of diseases. It is unknown if altered nuclear morphology contributes to pathology, and answering this question requires a better understanding of the mechanisms that control nuclear size and shape. In this review, we discuss recent advances in our understanding of the mechanisms that regulate nuclear morphology, focusing on nucleocytoplasmic transport, nuclear lamins, the endoplasmic reticulum, the cell cycle, and potential links between nuclear size and size regulation of other organelles. We then discuss the functional significance of nuclear morphology in the context of early embryonic development. Looking toward the future, we review new experimental approaches that promise to provide new insights into mechanisms of nuclear size control, in particular microfluidic-based technologies, and discuss how altered nuclear morphology might impact chromatin organization and physiology of diseased cells.

KEYWORDS: Cancer, cell size, chromatin, developmental scaling, endoplasmic reticulum, microfluidics, nuclear lamina, nuclear shape regulation, nuclear size regulation, nucleocytoplasmic transport, organelle size

Introduction

Size and shape are distinctive aspects of nuclear structure. Within a given cell type, nuclear size is generally maintained within a defined range. Changes in stereotyped nuclear morphologies are associated with a wide range of disease states. In each of these instances, it is unclear if altered nuclear size or shape contributes to the pathology or is a secondary effect of disease. In order to answer these questions, we require a better understanding of the basic cell biological mechanisms that contribute to the maintenance of normal nuclear size and shape. In this review, we discuss recent studies that have provided new insights into mechanisms of nuclear size regulation. While the primary focus of this review is nuclear size, we also include some discussion of factors that affect nuclear shape, as altered nuclear shape may reflect changes in nuclear size. In particular, it has been proposed that changes in nuclear size may manifest as altered nuclear shape, so as to preserve a constant ratio of nuclear-to-cytoplamic (N/C) volume that is important for proper cell function.1,2 We end the review with some thoughts on the potential functional significance of nuclear morphology in normal development and disease.

Nucleocytoplasmic transport and nuclear morphology

Proteins moving between the nucleoplasm and cytoplasm pass through the nuclear pore complex (NPC), which is important for selective nucleocytoplasmic transport and nuclear permeability. The NPC is composed of ∼30 nucleoporins (Nups) present in multiple copies, with Nups typically organized into sub-complexes.3-5 The cylindrical NPC core spans the nuclear envelope (NE) through a pore formed by the fusion of the inner nuclear membrane (INM) and outer nuclear membrane (ONM).6,7 Nucleocytoplasmic transport involves nuclear transport factors, including importins that bind cargos that contain a nuclear localization signal (NLS) and exportins that bind cargos with a nuclear export signal (NES). Certain Nups influence nuclear morphology. For example, Nup1 and Nup60 contain amphipathic helices that impart curvature to the INM, and overexpression of Nup1/Nup60 amphipathic helices in yeast led to deformation of the NE.8 Overexpression of Nup53 in yeast caused formation of intranuclear double membrane lamellae that lined the INM.9 In Xenopus, depletion of Nup188 increased nuclear size through increased import of INM proteins,10 and Arabidopsis thaliana deficient for Nup136 exhibited spherical rather than ellipsoid nuclei.11

Changes in NPC composition can impact nucleocytoplasmic transport and nuclear size. NPC differences in macronuclei (MAC) and micronuclei (MIC) of the ciliated protozoan Tetrahymena thermophila determine the differential nuclear import of MAC-specific or MIC-specific linker histones. MAC and MIC are 2 morphologically and functionally distinct nuclei within the same cell. MIC is smaller, transcriptionally inert, and contains a diploid genome originating from the zygote. MAC, on the other hand, is much larger and generated by programmed DNA rearrangements and amplifications. Loss of MAC- or MIC-specific linker histones leads to nuclear enlargement of the MAC or MIC, respectively, demonstrating that reduced chromatin compaction increases nuclear size in a nucleus-specific manner.12 Four Nup98 homologs showed differential localization in MAC and MIC nuclei, with 2 being specifically targeted to the MIC and 2 to the MAC. MacNup98A and MacNup98B possess typical FG-repeats, specifically repeats of the amino acid sequence GLFG, which interact with nuclear transport factors. In place of these GLFG repeats, MicNup98A and MicNup98B contain atypical importin docking repeats consisting of the amino acid sequence NIFN or SIFN. Nucleoporin domain swapping experiments were performed to test the model that GLFG repeats block import of MIC cargos while NIFN repeats block import of MAC cargos. When the N-terminal GLFG repeats of MacNup98A were fused to the C-terminal domain of MicNup98A (BigMic), the chimera localized to the MIC nucleus, reduced micronuclear linker histone import, and increased MIC size. Conversely, a fusion protein consisting of the C-terminus of MacNup98A joined to the N-terminal NIFN repeat domain of MicNup98A (BigMac) was targeted to the MAC nucleus, macronuclear linker histone import was reduced, and MAC size increased. Collectively, these data suggest that GLFG/NIFN repeats help to prevent misdirected protein transport to a given nucleus, thereby impacting nuclear size in T. thermophila.13 Interesting questions that arise from these studies are if linker histones are the only importin cargos necessary to induce these nuclear size differences, and whether linker histones impact nuclear size by altering chromatin structure or changing gene expression.

NPC number and density could theoretically impact nuclear size as well. However, comparing different cell types and organisms revealed an inverse relationship between NPC density and nuclear volume,14 with NPC number being controlled independently of nuclear volume and surface area.15 Studies in Xenopus showed that increased nuclear expansion rates could be uncoupled from increased NPC numbers.10 Furthermore, NPC assembly and nuclear expansion are independently regulated in mammalian tissue culture cells, as blocking interphasic NPC assembly in HeLa cells did not alter nuclear expansion or size.16,17 On the other hand, mutations that cause NPC clustering and/or mislocalization frequently give rise to altered nuclear morphology.18-21 Taken together, NPC composition seems to contribute more to the regulation of nuclear size than NPC number or density.

Nuclear lamins and nuclear morphology

Structural elements of the NE play important roles in defining nuclear size. The nuclear lamina, a meshwork of lamin intermediate filaments that lines the INM, is one of the major structures implicated in the regulation of nuclear morphology in metazoans.22-26 The nuclear lamina is important for chromatin organization, DNA metabolism, and providing mechanical strength to the nucleus. Four major lamin isoforms constitute the nuclear lamina in vertebrate cells – lamins A and C (alternatively spliced products of the LMNA gene), lamin B1 (encoded by LMNB1), and lamin B2 (encoded by LMNB2). Lamins B3 and C2 are found in germline cells and are products of alternative splicing of the LMNB2 and LMNA genes, respectively.27

General lamin structure includes an N-terminal globular head domain, a central α helical rod domain, and an immunoglobulin like C-terminal domain with NLS.28,29 Lamin monomers interact through their central coiled coil α helical domains to form 50 nm long dimers,30,31 which in turn interact in a head-to-tail manner to form higher order lamin polymer structures.32-36 Although the nuclear lamina is apposed to the INM, ∼10% of A-type lamins localize to the nuclear interior and interact with the chromatin and nucleoplasmic proteins, such as pRB and PCNA, rather than assembling into large polymers.37-40 In addition, interphase phosphorylation of lamin A induces its redistribution from the NE to nucleoplasm,41,42 and how a nucleoplasmic pool of lamins might influence nuclear morphology is an open question. Lamins also play a role in resisting dynein-mediated clustering of NPCs via the dynein adapter BICD2,43 thus lamins may indirectly contribute to proper nuclear morphology by preventing NPC aggregation that has been linked to aberrant nuclear membrane structures.18

Lamin expression and nuclear size are often correlated. Changes in lamin isoform expression during frog, chicken, and mouse development coincide with reductions in nuclear size.44-46 During granulopoiesis, lamin A/C expression is downregulated in neutrophils, leading to more deformable nuclei that facilitate cell passage through narrow constrictions.47 Nuclear volume also influences cell migration efficiency,48 and expression of certain lamin mutants or altering lamin expression levels affect nuclear deformability and cell migration.49-52 Knocking down lamin B1 in HeLa cells led to an increase in lamina meshwork size, formation of NE blebs enriched in lamin A/C, and increased nucleoplasmic lamin A mobility.53 Reduced lamin B1 levels are frequently associated with altered nuclear and cell shape and increased cellular senescence.54-60 Abnormal lamin localization and expression correlate with aberrant nuclear size in various disease states, notably cancer.61 For example, lamin B1 expression is elevated in prostate cancer, and lamin B1 expression levels directly correlate with tumor stage in hepatocellular carcinoma.62,63 Reduced lamin A/C levels are detected in small-cell lung carcinoma (SCLC) relative to non-SCLC, which might contribute to the differences in nuclear morphology between these 2 cancers.64,65 LAP2β, a lamina associated protein that connects the lamina and chromatin, is highly expressed in colorectal adenocarcinoma and SCLC, potentially contributing to nuclear enlargement in these cancers.66

Nucleocytoplasmic transport and lamin import regulate nuclear size in Xenopus. The eggs, cells, and nuclei of X. laevis are larger than those of X. tropicalis, and nuclear import rates differ in egg extracts from these 2 species, with X. tropicalis nuclei exhibiting slower import rates than X. laevis nuclei. The levels of 2 nuclear transport factors, importin α and NTF2, differ between the 2 extracts, and altering the levels of these 2 proteins was almost sufficient to account for the differences in nuclear size and import between these 2 species.67 Lamin B3, the major lamin type found in the egg, was found to be one of the imported cargos accounting for these differences in nuclear size, which is consistent with the observation that depletion of lamin B3 from egg extract blocks nuclear growth.67-69 Ectopic addition of lamin B3 to Xenopus egg extract increased the rate of nuclear growth,67 with the lamin immunoglobulin fold being required for post-mitotic lamina assembly and NE growth.23 It has recently been shown that nuclear size is sensitive to the total lamin concentration in Xenopus egg and embryo extracts, with low and high concentrations increasing and decreasing nuclear size, respectively. Recombinant lamin B1, B2, B3, and A similarly affected nuclear size when tested individually or in combination. Altering lamin levels in vivo, both in Xenopus embryos and mammalian tissue culture cells, also influenced nuclear size in a concentration-dependent manner.22

Developmental nuclear scaling in Xenopus embryos also depends on nuclear import capacity and lamins. Early Xenopus embryonic development is a robust system to study cellular scaling mechanisms in the absence of DNA ploidy changes because cell division is rapid with no overall change in the size of the embryo itself. The 1.2 mm fertilized egg undergoes 12 rapid synchronous cell divisions (each approximately 30 min) to produce several thousand 50 µm cells at the midblastula transition (MBT).70 Nuclear size decreases throughout early embryonic development in both X. laevis and X. tropicalis.67,71,72 Nuclear size reductions prior to the MBT correlate with reduced bulk import rates and levels of cytoplasmic importin α. Ectopic importin α expression was sufficient to increase nuclear size in pre-MBT embryos, while expression of both importin α and lamin B3 was required to increase nuclear size in later developmental stages.67,71 Experiments in C. elegans similarly demonstrated the involvement of nuclear transport and lamins in nuclear size regulation.73,74

In pre-MBT Xenopus embryos, nuclei expand throughout interphase, while at the MBT and beyond nuclei reach a steady-state size that is smaller than nuclei in pre-MBT embryos. A 3-fold decrease in NE surface area occurs between the MBT and gastrulation (stages 10.5–12).67,71 When large nuclei assembled in Xenopus egg extract were incubated in gastrula stage embryo extract, they became smaller. This nuclear shrinkage was dependent on conventional protein kinase C (cPKC) activity and correlated with removal of lamins from the NE. Based on these data, it was proposed that nuclear recruitment of cPKC leads to interphase phosphorylation of lamins that alters their residence time at the NE and contributes to reductions in nuclear size. This activity might account for the post-MBT developmental scaling of nuclear size in Xenopus embryos, as cPKC activity and nuclear localization increase in embryos after the MBT.75,76

The endoplasmic reticulum and nuclear morphology

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) plays an important role in NE formation and regulating nuclear size and shape. The ER is an interconnected lipid bilayer membrane network, consisting of ER tubules and sheets, that is continuous with the NE. Post-mitotic NE reformation is initiated by the targeting of ER tubules to chromatin, through the action of ER-resident DNA binding proteins. This is followed by flattening of ER membranes around the developing nucleus,77 with final sealing of the NE accomplished by ESCRT-III.78,79 In mammalian tissue culture cells, the INM proteins MAN1, Lap2β, and lamin B receptor contribute to NE formation by anchoring ER membranes at the chromatin surface, promoting membrane spreading onto the chromatin.80 Subsequent expansion of the NE requires an intact ER network, as detachment of ER membranes from the NE by shear mechanical stress hampered nuclear growth in Xenopus extract, and withdrawing mechanical stress resulted in recovery of NE growth.77 Impairing the function of the AAA-ATPase p97, generally required for ER network maintenance, also inhibited NE expansion.81 Conversely, selective macroautophagy of ER and nuclear membranes has recently been observed in S. cerevisiae. Atg39, a perinuclear-localized autophagy receptor, regulates autophagic sequestration of NE. Under nitrogen starvation conditions, cells lacking Atg39 exhibited lobulated and distorted nuclei with a concomitant loss of viability.82

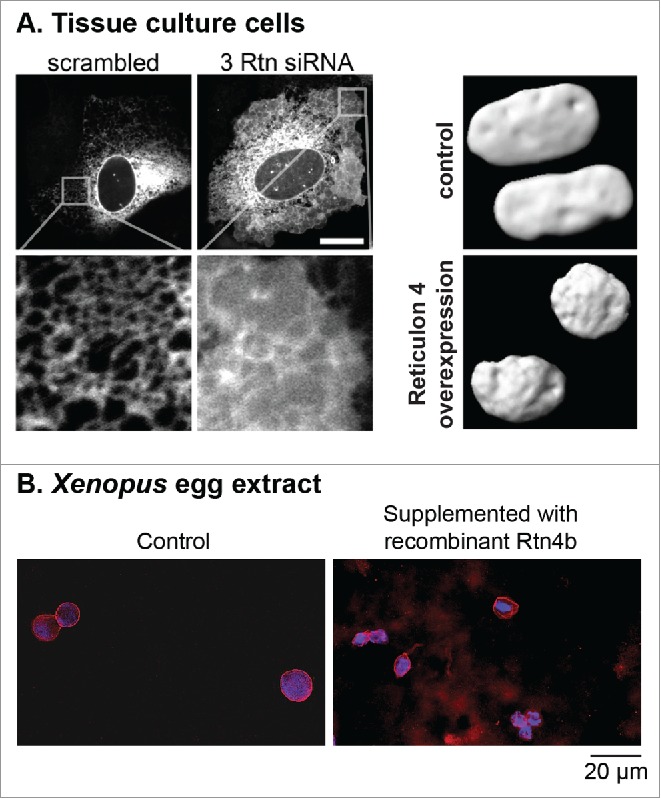

Structural proteins of the ER network contribute to NE morphology by affecting the proportion of ER tubules to ER sheets. Reticulon (Rtn) proteins are responsible for shaping the ER tubules and stabilizing membranes with high curvature by inserting a hydrophobic wedge into lipid bilayers.83-85 In tissue culture cells, Rtn overexpression increased ER tubulation and reduced NE surface area, while Rtn depletion by siRNA knockdown reduced ER tubulation and increased nuclear size (Fig. 1A).86 NE formation was inhibited in Xenopus egg extract supplemented with a neutralizing Rtn4 antibody,77 and ectopic Rtn4 expression in early Xenopus embryos led to altered nuclear size.71 Furthermore, ectopic addition of recombinant Rtn4b to Xenopus egg extract decreased the rate of nuclear expansion, leading to an ∼2.4-fold reduction in nuclear cross-sectional area (Fig. 1B). These observations suggest a tug-of-war relationship between membranes of the ER and NE.80,86,87 Other ER structural proteins like Climp63 and atlastins, which set ER sheet width and generate 3-way junctions, respectively, might also impact nuclear morphology. For example, Climp63 levels might affect the relative amounts of ER sheets versus tubules,88 and atlastins might control expansion of the NE by regulating the extent of ER tubule branching.89,90 Also of potential relevance are members of the conserved Lunapark protein family that reside at ER 3-way junctions in yeast and mammalian cells, reducing ER 3-way junction dynamics and preventing ER tubule fusion.91 Membrane biogenesis can also impact nuclear morphology. Lipin is a phosphatidate phosphatase important in glycerolipid biosynthesis, and inactivation of lipin or genes that regulate lipin leads to disorganization of peripheral ER structures with concomitant defects in NE morphology in C. elegans and yeast.2,92-94

Figure 1.

Reticulon expression levels affect ER structure and nuclear size. (A) In the left panel, the ER is visualized in U2OS cells with a Sec61-GFP construct. Knockdown of Rtn1, Rtn3, and Rtn4 by siRNA (labeled 3 Rtn siRNA) leads to less ER tubulation and more ER sheets, with a concomitant increased rate of post-mitotic nuclear formation. The scale bar is 20 µm. In the right panel, nuclei in U2OS cells are visualized with GFP-NLS at 160 minutes after nuclear formation. In cells overexpressing V4-Rtn4, nuclei are smaller due to slower nuclear expansion. Images used with permission from.86 (B) Nuclei were assembled in Xenopus laevis egg extract for 45 min. The extract was then supplemented with 67 nM recombinant purified Rtn4b protein and incubated for another 45 min. Nuclei were fixed, spun onto coverslips, and stained with mAb414 to visualize the NPC and NE (red) and Hoechst to visualize the DNA (blue). Nuclear cross-sectional areas were quantified. Exogenous addition of Rtn4b led to an ∼2.4-fold reduction in nuclear cross-sectional area (our unpublished data).

The interplay between the ER and nuclear lamina may be important in determining steady state nuclear size. During interphase, nuclei expand and import nuclear lamins into the forming NE, strengthening the lamina meshwork. The increased mechanical force exerted by the expanding lamina might resist the ability of the ER network to extract membrane from the NE, so that optimal lamin import promotes NE growth.22 As already discussed, lamins are phosphorylated during interphase,42,95-97 and increased phosphorylation of lamins by cPKC may result in increased loss of lamins from the NE and/or altered nuclear lamina dynamics. This phenomenon might be compensated for by retraction of NE membrane back into the ER, resulting in decreased NE surface area and constant nuclear lamina density, potentially contributing to the steady-state regulation of nuclear size.75

Interestingly, Rtn levels are sometimes altered in different cancers, potentially contributing to cancer-associated abnormalities in nuclear morphology. Rtn4a overexpression has been observed in malignant brain tumor cells, and sufficiently high Rtn expression levels could have a dominant negative effect leading to increased nuclear size, as observed in Xenopus.71 Downregulation of Rtn4 Interacting Protein 1 (Rtn4IP1) has been observed in thyroid cancers,98,99 potentially decreasing the efficiency with which Rtn4 shapes tubulated ER and leading to an increase in nuclear size.100 As another example, Rtn1 is upregulated in malignant pancreatic carcinoma, diffusely infiltrating gliomas, and neuroendocrine tumors,98,101-103 again possibly influencing ER and nuclear morphology in these cancers.

Nuclear and organelle scaling relative to cell size

Cell growth and division influence the sizes of intracellular organelles, but mechanisms responsible for regulating how organelle size scales relative to cell size are largely unknown.104 It is well established that nuclear size varies as a function of cell size and that the N/C volume ratio is a tightly regulated cellular feature. Varying the sizes of S. cerevisiae cells by mutation or differing growth conditions demonstrated that large cells possess large nuclei and smaller cells exhibit smaller nuclei, maintaining a constant N/C volume ratio.105 Similar studies were performed in fission yeast S. pombe, where a constant N/C volume ratio was maintained over a 35-fold range of cell sizes. A 16-fold increase in DNA amount did not change nuclear size, demonstrating that ploidy has little effect on nuclear size in this system.106 Interestingly, nucleolar size scaled proportionately with nuclear and cell sizes in these yeast studies as well. Nucleolar size also exhibited a positive correlation with cell/nuclear size in early C. elegans embryos. Surprisingly, when embryo size was altered by various RNAi treatments, nucleolar size showed an inverse scaling relationship, in which large nucleoli assembled in small cells/nuclei and vice versa. The model proposed to explain this observation is that oocytes are maternally loaded with a fixed number, rather than a fixed concentration, of nucleolar components. As a result, the concentration of nucleolar proteins is higher in RNAi-treated embryos with small cells/nuclei, thus giving rise to larger nucleoli.107 Nucleolar assembly that depends on an intracellular phase transition could explain this behavior, and such concentration-dependent phase transitions might be a useful paradigm for understanding size scaling of other intracellular structures.108

Limiting component models have been invoked to explain size scaling of a variety of different organelles and intracellular structures.109 As these models may be relevant to nuclear size scaling, it is worth briefly touching on what is known about size scaling of other organelles. Centrosome size scales linearly with cell size in early embryonic stages of C. elegans development. A limiting component hypothesis has been suggested in which centrosome size is determined by cytoplasmic volume, which dictates the total amount of centrosomal components available for assembly.110 The size of mitochondrial networks directly correlates with cell size in S. cerevisiae, with aging mother cells showing a continual reduction in the mitochondria-to-cell size ratio over successive generations.111 How mitotic spindle size might influence nuclear size, and vice versa, is a particularly intriguing question. As discussed later in this review, microfluidic encapsulation of mitotic X. laevis egg extracts demonstrated that changes in cytoplasmic volume are sufficient to drive spindle length scaling that occurs during early X. laevis development.112-114 These data suggest that spindle scaling might be explained by limiting amounts of cytoplasmic components, acting in concert with other mechanisms that affect the activity of microtubule regulatory factors.115-117 For example, in early stages of Xenopus development, the kinesin-13 microtubule depolymerase kif2a is inhibited by importin α, but becomes activated later in development when the cytoplasmic importin α concentration decreases through redistribution to a membrane pool, thus giving rise to smaller spindles.118 As nuclear transport has been clearly implicated in nuclear size control, this function for importin α provides a potential link between size scaling of the spindle and nucleus.

Nuclear size in embryonic development

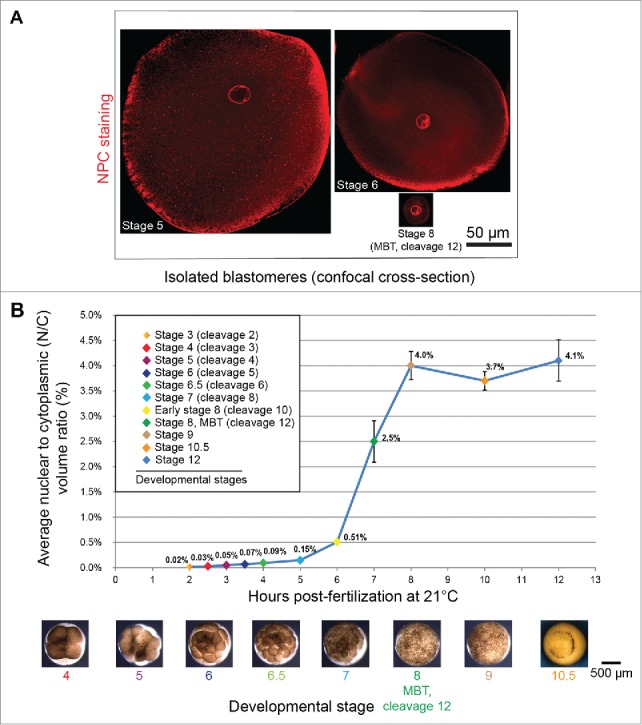

For a given cell type, nuclear size is generally maintained within a defined range, and the size of the nucleus tends to scale as a function of cell size.119 How nuclear size might impact cell function and physiology is an important question. As already described, Xenopus development offers a useful animal model to investigate scaling relationships. During early X. laevis embryogenesis, nuclear volume decreases on average ∼3-fold up to the MBT, while cytoplasmic volume shows a much more dramatic ∼70-fold reduction in volume. As a consequence, the average N/C volume ratio increases abruptly prior to the MBT (Fig. 2). The MBT is associated with a dramatic increase in zygotic transcription and acquisition of slower, asynchronous cell cycles. Identifying the mechanisms that contribute to proper MBT timing has been an area of active research for decades. Experimentally increasing nuclear volume in embryos by microinjecting different nuclear scaling factors, including import proteins, lamins, and reticulons, increased the N/C volume ratio in pre-MBT embryos and led to premature activation of zygotic gene transcription and early onset of longer cell cycles. Conversely, decreasing the N/C volume ratio delayed zygotic transcription and resulted in additional rapid cell divisions.71 Similarly, in early C. elegans embryonic development, cell cycle duration is correlated with the N/C volume ratio.120 These data show that nuclear size and the N/C ratio can impact timing of the MBT, providing insight into the physiological significance of the relationship between cell and nuclear size. These findings are potentially relevant to cancer where deviations from normal N/C volume ratios are frequently observed.100

Figure 2.

Nuclear scaling in early Xenopus embryos. (A) Isolated blastomeres from different stage X. laevis embryos were stained with mAb414 antibody against the NPC and imaged by confocal microscopy. (B) Average nuclear and cell volumes were quantified for the indicated stages of development, and used to obtain average nuclear-to-cytoplasmic (N/C) volume ratios. Error bars are SE. Images used with permission from71.

Another factor that contributes to proper MBT timing in the Xenopus embryo is the ratio of DNA to cytoplasm.121,122 By varying the DNA content or cytoplasmic volume of early X. laevis embryos, it was shown that increasing the ratio of DNA to cytoplasm resulted in an earlier MBT.122,123 The proposed mechanism is that the egg is loaded with a fixed amount of DNA binding proteins that serve to inhibit the MBT. As development proceeds, cell number and total DNA amount increase exponentially in the embryo. Once a threshold amount of DNA is reached, there are insufficient numbers of MBT inhibitory molecules to sufficiently bind all DNA, thus leading to induction of the MBT.122,124 Several potential limiting DNA binding factors have been identified: histones,125 phosphatase PP2A,126 and DNA replication initiation factors.127 Another protein that acts though a limiting titration mechanism is RAD18, a ubiquitin ligase responsible for monoubiquitination of PCNA. It functions to silence the DNA damage checkpoint in Xenopus embryos prior to the MBT.128 Importantly, none of these factors appear to fully account for the proper regulation of MBT timing, so it seems likely that redundant mechanisms are involved, with both DNA amount and nuclear volume contributing. We propose that nuclear volume may be relevant to the DNA titration model, by regulating intranuclear concentrations of the limiting DNA binding factors.71

Just as nuclear size affects MBT cell cycle length, cell cycle progression also impacts nuclear morphology. Identified in Xenopus, Dppa2 and REEP3/4 are required to remove microtubules and ER membrane, respectively, from chromatin at the end of mitosis to ensure a nucleus of the proper size and shape forms in the subsequent interphase.129,130 In C. elegans, partial inactivation of polo-like kinase PLK-1 leads to defects in NE breakdown giving rise to 2 nuclei that fail to merge into one.131 In yeast, formation of NE flares adjacent to the nucleolus in response to excess membrane production or mitotic arrest is dependent on polo kinase Cdc5.132,133 A question for future research is precisely how kinases with well-established roles in mitosis, including cyclin-dependent kinases, polo kinases, and PKC, contribute to the maintenance of proper nuclear morphology.

Given the potential impact of the cell cycle on nuclear morphology, it is worth considering the interplay between size scaling of mitotic structures and the nucleus. Scaling of mitotic spindle length as a function of cell size during developmental progression is conserved across metazoans,134 as has already been discussed in the context of early Xenopus embryogenesis. Comparing nearly 100 natural isolates of C. elegans showed that selection for cell size, that impacts spindle size, can account for differences in spindle size that span over 100 million years of evolution.135 Furthermore, during early C. elegans development the physical length of condensed mitotic chromosomes scales with cell and nuclear size, such that a smaller nucleus contains shorter chromosomes as measured just prior to NE breakdown when chromosome condensation is nearly complete.74 Similar evolutionary pressures may act to control the size of the nucleus as a function of cell and embryo size. As already discussed, multiple mechanisms likely contribute to the proper regulation of nuclear size. Regardless of mechanism, nuclear size normally scales with cell size, suggesting that correct nuclear scaling is important for nuclear, cell, and organismal function, as is particularly evidenced in the case of early embryonic development.

New technologies to study nuclear size regulation

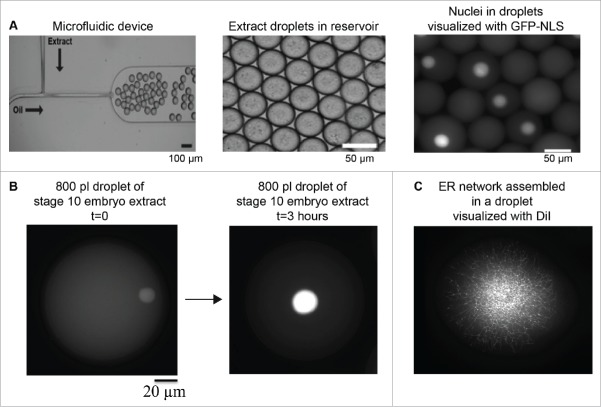

During early Xenopus development, reductions in nuclear size might be regulated by changes in the composition of the embryonic cytoplasm and/or reductions in cytoplasmic volume as cells become smaller. We have already reviewed data showing how developmentally regulated changes in cytoplasmic composition contribute to nuclear scaling, including roles for nuclear import and cPKC activity. More recently, microfluidic-based technologies enable the testing of how cytoplasmic volume directly impacts nuclear size (Fig. 3). Encapsulating X. laevis egg or embryo extracts in droplets of tunable and defined size is becoming a popular approach to investigate mechanisms of organelle scaling. The open nature of the extract system allows for precise manipulation of cytoplasmic composition, for instance through the addition or depletion of specific proteins, while microfluidic droplet generating devices allow for exquisite control of cytoplasmic volume and droplet shape. This approach facilitates the study of how organelle size is regulated by varying cytoplasmic volumes, limiting components in fixed cytoplasmic volumes, and sensing of droplet shape and boundaries.136

Figure 3.

Microfluidic encapsulation technology to study organelle size scaling. (A) A standard microfluidic T-junction device is shown. At the junction where oil/surfactant and X. laevis egg extract mix, droplets are generated. Droplet size can be tuned by altering device geometry and flow rates. Image courtesy of John Oakey and Jay Gatlin. (B) Large 800 pl droplets containing stage 10 X. laevis embryonic cytoplasm and endogenous nuclei are shown. Nuclei are visualized by import of GFP-NLS. Over the course of ∼3 hours at room temperature, nuclear size expands (our unpublished data). (C) Partially fractionated X. laevis egg extract was encapsulated in a droplet, and ER network formation was visualized with DiI (our unpublished data).

Microfluidic techniques have provided insight into scaling of the mitotic spindle, where droplet encapsulation of X. laevis egg cytoplasm demonstrated that small spindles form in small droplets and larger spindles form in larger droplets. Interestingly, spindle length was more sensitive to cytoplasmic volume than droplet shape, arguing against a boundary-sensing model of spindle length regulation.112,113 As cytoplasmic volume regulates spindle length scaling, these data support a limiting component model of spindle size regulation. A variant of this approach, in which X. laevis egg extract was pumped into microfluidic channels of varying dimensions, demonstrated that the rate of nuclear growth correlated with the volume of accessible cytoplasm. Additionally, when X. laevis egg extract was treated with a dynein inhibitor prior to encapsulation in the microchannels, nuclear expansion was greatly inhibited, implicating a microtubule- and dynein-based mechanism of nuclear size regulation.137

Other new technologies allow for measuring the entire transcriptomes of individual cells, by coupling microfluidic encapsulation of individual cells with next generation sequencing.138 For example, whereas only 5 mouse retinal cell types were previously known, this so-called Drop-seq method identified 39 distinct cell types based on individual cell profiles.139 We envision coupling these approaches with encapsulation of Xenopus extracts, in order to test how cytoplasmic volume impacts the onset of zygotic transcription associated with the MBT.71

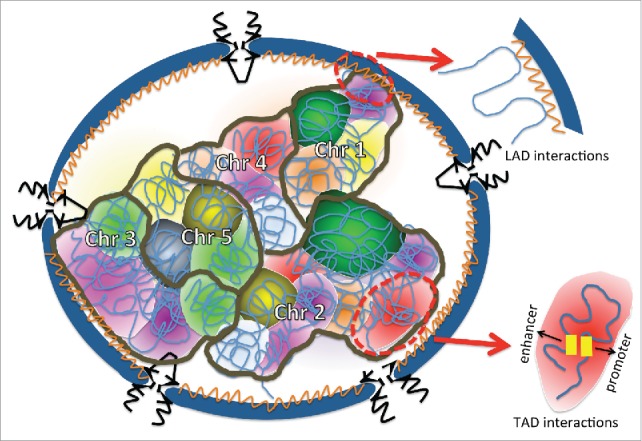

Does nuclear morphology affect chromatin organization?

The genome is highly compacted in the eukaryotic nucleus and each chromosome generally occupies a preferred but not fixed position. Chromosomes near the interior of the nucleus tend to be gene-dense while genes at the periphery are usually poorly expressed and associated with the nuclear lamina.140,141 How nuclear size and morphology affect chromosomal positioning and gene expression is an important unanswered question. Additionally, it has been showed that there is a correlation between nuclear volume and genome size in animals and plants.142,143 Here we discuss some aspects of chromatin organization that may be influenced by nuclear size (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Chromosomes are spatially organized within the nucleus. The NE is blue, and the nuclear lamina is the orange structure lining the nucleoplasmic face of the NE. NPCs are black and inserted into the NE. Each chromosome is outlined in brown and is composed of multiple different TADs that are depicted with different colors. An example of the type of chromatin interaction occurring within a TAD is shown within the red oval. LAD interactions of chromatin with the nuclear lamina are also depicted. It is easy to imagine how a change in nuclear volume and/or shape might impact this chromosomal organization.

Topologically associated domains (TADs) in metazoan genomes are chromosomal regions that tend to be in close proximity to one another. Within a single TAD there are interactions and chromatin loops between cis-regulatory regions, such as enhancers, promoters, and insulators, which regulate gene expression. Neighboring TADs are isolated from one another by boundary elements, including the insulator binding protein CTCF, housekeeping genes, and short interspersed element retrotransposons.144,145 The importance of CTCF for chromosome organization has been demonstrated by changing the orientation or position of CTCF binding sites, which leads to altered chromatin looping and 3D chromosome architecture.146,147 While some aspects of TAD organization are conserved among different cell types,144 changes in TAD interactions are associated with cell differentiation and response to environmental signals,144,148-151 demonstrating plasticity in this level of chromatin positioning. How nuclear volume and shape might influence TAD organization is an open question.

Lamina-associated domains (LADs) are transcriptionally repressed chromatin domains localized at the NE. LADs are generally enriched in repressive histone modifications,152 and repositioning of active genes to the lamina can result in their repression. For instance, in human embryonic stem cells and derived embryoid bodies, active circadian rhythm genes are silenced when moved into LADs by PARP1 and its co-factor CTCF.153 The nuclear lamina provides an interaction platform among LADs, and lamins regulate this chromatin organization through diverse interactions. For example, Drosophila B-type lamins interact with the actin nucleation protein Wash to maintain proper LAD and chromosome organization.154 Deletion of B-type lamins in mouse embryonic stem cells reduced interactions between LADs and the nuclear lamina,155 and cortical neurons in lamin B1 deficient mice exhibit misshapen nuclei with nuclear blebs.156 As discussed earlier in this review, lamins and components of the nuclear lamina affect nuclear size, which we speculate could influence LAD organization.

Besides the lamina, other nuclear components can affect chromosome structure and gene expression. In yeast, some nuclear transport factors and Nups bind to transcriptionally active genes.157 Loss of Drosophila Nup62 or Nup93 alters chromatin attachments to the NPC,158 and depletion of Xenopus Nup188 increases nuclear size, potentially impacting chromatin localization.10 Centromeric regions of human chromosomes also adopt defined positions within the 3-dimensional space of the nucleus that are likely important for nuclear function and may be influenced by altered nuclear size in cancer.159

Novel methods are being developed to investigate chromatin and chromosome structure. We anticipate these approaches will be useful in ascertaining how altered nuclear morphology impacts global chromatin organization. One of the most widely used methods to detect higher-order chromatin structure is the chromosome conformation capture (3C) family of techniques.146,153,160 Chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq), micrococcal nuclease sequencing (MNase-seq), and chromatin immunoprecipitation exonuclease (ChIP-exo) methodologies provide information over the ∼1–150 bp length scale, allowing for analysis of nucleosome fiber folding 149,161-164. While these types of approaches provide information on populations of cells, single-cell approaches have now become feasible. A modified DamID (DNA adenine methyltransferase identification) method enables genome-wide mapping in single human cells,144,147,165,166 and CRISPR-based approaches have been used to image individual chromosomal loci in live cells and in vitro extracts.167,168 To identify molecular mechanisms that contribute to proper chromatin organization, HIPMap (high-throughput imaging position mapping) was coupled with siRNA screening to identify human genome positioning factors, including chromatin remodelers, histone modifiers, and NE and NPC proteins.169 As we gain a better understanding of how proper chromosome positioning is established, it becomes possible to test how nuclear size and shape impact these pathways.

Nuclear morphology and disease

Aberrant nuclear morphology is associated with many diseases, most notably cancer in which altered nuclear size and shape are used by pathologists to assess the degree of malignancy.61,100,170 Chromosomal gains and losses, amplification or deletion of smaller genomic fragments, and changes in higher-order chromatin structure are all associated with cancer.171,172 Cancer-associated changes in nuclear morphology may disrupt normal chromatin positioning, gene expression, and DNA damage pathways, potentially contributing to disease progression. In a recent study, it was shown that loss of the developmentally regulated GATA6 transcription factor in ovarian cancer resulted in deformation of the NE, cytokinesis failure, and aneuploidy.173 Molecular mechanisms that may contribute to altered nuclear size and shape in cancer have been touched on throughout this review and comprehensively reviewed elsewhere.1,61,87,100, 170,174-176 An important question for future research is if correcting the altered nuclear morphology of cancer cells might mitigate disease.

Mutations in nuclear proteins contribute to other diseases. In mammalian cells, loss or mutation of NE structural proteins, such as emerin 177 and lamin A/C,178 cause altered nuclear morphology associated with diseases such as muscular dystrophy,179 premature aging,180 laminopathies,181 and cancer.182 For example, a heterozygous mutation in exon 11 of LMNA results in Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome, a rare premature aging disease associated with alterations in nuclear shape and structure.183 Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia result from hexanucleotide repeat expansions in the C9orf72 gene, which leads to an inhibition of nuclear protein import and abnormal nuclear architecture.184,185 Torsin proteins are ER membrane embedded AAA+ ATPases. While most torsins are found in the peripheral ER, torsinA (encoded by TOR1A) is also localized in the INM where it affects nuclear morphology. An in-frame deletion in the TOR1A gene that removes a single glutamic acid residue (ΔE-torsinA) causes the neurodevelopmental disorder DYT1 dystonia and results in redistribution of torsinA from the ER to the NE.186-189 In both torsinA null and homozygous ΔE-torsinA knockin mice, the neuronal NE exhibited ultrastructural abnormalities, including INM-derived vesicles within the NE lumen190. Other data indicate that torsinA affects connections between the INM and ONM.191 Mutating OOC-5, the C. elegans homolog of torsinA, led to abnormal germ cell and intestinal nuclear morphologies, with vesicle-like blebs present in the perinuclear space and protrusion of ONM into the cytoplasm.192

Nuclear architecture can also be targeted by pathogens. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) associates with particular Nups in order to integrate into transcriptionally active host genes that are located within 1 µm from the nuclear periphery, while avoiding heterochromatin regions in LADs,193 suggesting that host nuclear topology is an essential determinant of the HIV-1 life cycle. SINC is a type III secreted protein of Chlamydia psittaci. When Hela cells are infected by C. psittaci, SINC incorporates into the NE of the host cell nucleus and interacts with Nups, ELYS, lamin B1, and emerin, leading to alterations in nuclear shape and function in both infected cells and neighboring uninfected cells.194 Many diseases are associated with altered nuclear morphology, so identifying approaches to correct these morphological defects may lead to novel therapeutics.

Concluding remarks

Throughout this review, we have touched on some important outstanding questions in the field of nuclear morphology regulation. A variety of new experimental methodologies promise to provide new insights into the mechanisms that control nuclear size and shape. With a better handle on mechanism, it should become possible to directly address the functional significance of nuclear morphology, both in normal cells and in disease. How does nuclear morphology affect nuclear function and the morphology of other intracellular structures? How does nuclear volume impact chromatin positioning and gene expression? Does nuclear morphology represent a novel target for cancer therapeutics? Answers to these questions and others are hopefully forthcoming, as exciting work remains to elucidate the regulation of nuclear size and shape.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We thank Predrag Jevtić and Karen White for critical reading of the manuscript.

Funding

Research in the Levy laboratory is supported by the NIH/NIGMS (R15GM106318 and R01GM113028) and American Cancer Society (RSG-15-035-01-DDC).

References

- [1].Walters AD, Bommakanti A, Cohen-Fix O. Shaping the nucleus: Factors and forces. J Cell Biochem 2012; 113:2813-21; PMID:22566057; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/jcb.24178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Webster MT, McCaffery JM, Cohen-Fix O. Vesicle trafficking maintains nuclear shape in Saccharomyces cerevisiae during membrane proliferation. J Cell Biol 2010; 191:1079-88; PMID:21135138; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.201006083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Rout MP, Aitchison JD, Suprapto A, Hjertaas K, Zhao Y, Chait BT. The yeast nuclear pore complex: composition, architecture, and transport mechanism. J Cell Biol 2000; 148:635-51; PMID:10684247; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.148.4.635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Cronshaw JM, Krutchinsky AN, Zhang W, Chait BT, Matunis MJ. Proteomic analysis of the mammalian nuclear pore complex. J Cell Biol 2002; 158:915-27; PMID:12196509; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200-206106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Alber F, Dokudovskaya S, Veenhoff LM, Zhang W, Kipper J, Devos D, Suprapto A, Karni-Schmidt O, Williams R, Chait BT, et al.. The molecular architecture of the nuclear pore complex. Nature 2007; 450:695-701; PMID:18046406; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature06405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].D'Angelo MA, Hetzer MW. Structure, dynamics and function of nuclear pore complexes. Trends Cell Biol 2008; 18:456-66; PMID:18786826; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Hoelz A, Debler EW, Blobel G. The structure of the nuclear pore complex. Annu Rev Biochem 2011; 80:613-43; PMID:21495847; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060109-151030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Meszaros N, Cibulka J, Mendiburo MJ, Romanauska A, Schneider M, Kohler A. Nuclear pore basket proteins are tethered to the nuclear envelope and can regulate membrane curvature. Dev Cell 2015; 33:285-98; PMID:25942622; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.02.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Marelli M, Lusk CP, Chan H, Aitchison JD, Wozniak RW. A link between the synthesis of nucleoporins and the biogenesis of the nuclear envelope. J Cell Biol 2001; 153:709-24; PMID:11352933; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.153.4.709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Theerthagiri G, Eisenhardt N, Schwarz H, Antonin W. The nucleoporin Nup188 controls passage of membrane proteins across the nuclear pore complex. J Cell Biol 2010; 189:1129-42; PMID:20566687; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200912045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Tamura K, Hara-Nishimura I. Involvement of the nuclear pore complex in morphology of the plant nucleus. Nucleus 2011; 2:168-72; PMID:21818409; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/nucl.2.3.16175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Shen X, Yu L, Weir JW, Gorovsky MA. Linker histones are not essential and affect chromatin condensation in vivo. Cell 1995; 82:47-56; PMID:7606784; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90051-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Iwamoto M, Mori C, Kojidani T, Bunai F, Hori T, Fukagawa T, Hiraoka Y, Haraguchi T. Two distinct repeat sequences of Nup98 nucleoporins characterize dual nuclei in the binucleated ciliate tetrahymena. Curr Biol 2009; 19:843-7; PMID:19375312; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cub.2009.03.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Maul GG, Deaven L. Quantitative determination of nuclear pore complexes in cycling cells with differing DNA content. J Cell Biol 1977; 73:748-60; PMID:406262; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.73.3.748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Maul GG, Deaven LL, Freed JJ, Campbell GL, Becak W. Investigation of the determinants of nuclear pore number. Cytogenet Cell Genet 1980; 26:175-90; PMID:6966999; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1159/000131439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Maeshima K, Iino H, Hihara S, Funakoshi T, Watanabe A, Nishimura M, Nakatomi R, Yahata K, Imamoto F, Hashikawa T, et al.. Nuclear pore formation but not nuclear growth is governed by cyclin-dependent kinases (Cdks) during interphase. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2010; 17:1065-71; PMID:20711190; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nsmb.1878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Maeshima K, Iino H, Hihara S, Imamoto N. Nuclear size, nuclear pore number and cell cycle. Nucleus 2011; 2:113-8; PMID:21738834; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/nucl.2.2.15446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Cohen M, Feinstein N, Wilson KL, Gruenbaum Y. Nuclear pore protein gp210 is essential for viability in HeLa cells and Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Biol Cell 2003; 14:4230-7; PMID:14517331; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1091/mbc.E03-04-0260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ryan KJ, McCaffery JM, Wente SR. The Ran GTPase cycle is required for yeast nuclear pore complex assembly. J Cell Biol 2003; 160:1041-53; PMID:12654904; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200209116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ryan KJ, Zhou Y, Wente SR. The karyopherin Kap95 regulates nuclear pore complex assembly into intact nuclear envelopes in vivo. Mol Biol Cell 2007; 18:886-98; PMID:17182855; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1091/mbc.E06-06-0525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Titus LC, Dawson TR, Rexer DJ, Ryan KJ, Wente SR. Members of the RSC chromatin-remodeling complex are required for maintaining proper nuclear envelope structure and pore complex localization. Mol Biol Cell 2010; 21:1072-87; PMID:20110349; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1091/mbc.E09-07-0615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Jevtic P, Edens LJ, Li X, Nguyen T, Chen P, Levy DL. Concentration-dependent Effects of Nuclear Lamins on Nuclear Size in Xenopus and Mammalian Cells. J Biol Chem 2015; 290:27557-71; PMID:26429910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Shumaker DK, Lopez-Soler RI, Adam SA, Herrmann H, Moir RD, Spann TP, Goldman RD. Functions and dysfunctions of the nuclear lamin Ig-fold domain in nuclear assembly, growth, and Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005; 102:15494-9; PMID:16227433; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0507612102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Dechat T, Pfleghaar K, Sengupta K, Shimi T, Shumaker DK, Solimando L, Goldman RD. Nuclear lamins: major factors in the structural organization and function of the nucleus and chromatin. Genes Dev 2008; 22:832-53; PMID:18381888; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.1652708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Dechat T, Adam SA, Taimen P, Shimi T, Goldman RD. Nuclear lamins. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2010; 2:a000547; PMID:20826548; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/cshperspect.a000547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Gruenbaum Y, Margalit A, Goldman RD, Shumaker DK, Wilson KL. The nuclear lamina comes of age. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2005; 6:21-31; PMID:15688064; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrm1550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Parnaik VK, Chaturvedi P, Muralikrishna B. Lamins, laminopathies and disease mechanisms: possible role for proteasomal degradation of key regulatory proteins. J Biosci 2011; 36:471-9; PMID:21799258; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s12038-011-9085-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Dittmer TA, Misteli T. The lamin protein family. Genome Biol 2011; 12:222; PMID:21639948; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/gb-2011-12-5-222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Wilson KL, Berk JM. The nuclear envelope at a glance. J Cell Sci 2010; 123:1973-8; PMID:20519579; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/jcs.019042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Herrmann H, Bar H, Kreplak L, Strelkov SV, Aebi U. Intermediate filaments: from cell architecture to nanomechanics. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2007; 8:562-73; PMID:17551517; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrm2197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Parry DA. Microdissection of the sequence and structure of intermediate filament chains. Adv Protein Chem 2005; 70:113-42; PMID:15837515; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0065-3233(05)70005-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Aebi U, Cohn J, Buhle L, Gerace L. The nuclear lamina is a meshwork of intermediate-type filaments. Nature 1986; 323:560-4; PMID:3762708; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/323560a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Ben-Harush K, Wiesel N, Frenkiel-Krispin D, Moeller D, Soreq E, Aebi U, Herrmann H, Gruenbaum Y, Medalia O. The supramolecular organization of the C. elegans nuclear lamin filament. J Mol Biol 2009; 386:1392-402; PMID:19109977; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.12.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Goldberg MW, Huttenlauch I, Hutchison CJ, Stick R. Filaments made from A- and B-type lamins differ in structure and organization. J Cell Sci 2008; 121:215-25; PMID:18187453; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/jcs.022020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Herrmann H, Aebi U. Intermediate filaments: molecular structure, assembly mechanism, and integration into functionally distinct intracellular Scaffolds. Annu Rev Biochem 2004; 73:749-89; PMID:15189158; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Stick R, Goldberg MW. Oocytes as an experimental system to analyze the ultrastructure of endogenous and ectopically expressed nuclear envelope components by field-emission scanning electron microscopy. Methods 2010; 51:170-6; PMID:20085817; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Dorner D, Gotzmann J, Foisner R. Nucleoplasmic lamins and their interaction partners, LAP2alpha, Rb, and BAF, in transcriptional regulation. FEBS J 2007; 274:1362-73; PMID:17489094; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05695.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Kolb T, Maass K, Hergt M, Aebi U, Herrmann H. Lamin A and lamin C form homodimers and coexist in higher complex forms both in the nucleoplasmic fraction and in the lamina of cultured human cells. Nucleus 2011; 2:425-33; PMID:22033280; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/nucl.2.5.17765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Olins AL, Hoang TV, Zwerger M, Herrmann H, Zentgraf H, Noegel AA, Karakesisoglou I, Hodzic D, Olins DE. The LINC-less granulocyte nucleus. Eur J Cell Biol 2009; 88:203-14; PMID:19019491; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ejcb.2008.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Simon DN, Wilson KL. Partners and post-translational modifications of nuclear lamins. Chromosoma 2013; 122:13-31; PMID:23475188; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00412-013-0399-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Buxboim A, Swift J, Irianto J, Spinler KR, Dingal PC, Athirasala A, Kao YR, Cho S, Harada T, Shin JW, et al.. Matrix elasticity regulates lamin-a,c phosphorylation and turnover with feedback to actomyosin. Curr Biol 2014; 24:1909-17; PMID:25127216; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cub.2014.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Kochin V, Shimi T, Torvaldson E, Adam SA, Goldman A, Pack CG, Melo-Cardenas J, Imanishi SY, Goldman RD, Eriksson JE. Interphase phosphorylation of lamin A. J Cell Sci 2014; 127:2683-96; PMID:24741066; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/jcs.141820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Guo Y, Zheng Y. Lamins position the nuclear pores and centrosomes by modulating dynein. Mol Biol Cell 2015; 26:3379-89; PMID:26246603; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1091/mbc.E15-07-0482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Stick R, Hausen P. Changes in the nuclear lamina composition during early development of Xenopus laevis. Cell 1985; 41:191-200; PMID:3995581; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90073-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Lehner CF, Stick R, Eppenberger HM, Nigg EA. Differential expression of nuclear lamin proteins during chicken development. J Cell Biol 1987; 105:577-87; PMID:3301871; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.105.1.577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Rober RA, Weber K, Osborn M. Differential timing of nuclear lamin A/C expression in the various organs of the mouse embryo and the young animal: a developmental study. Development 1989; 105:365-78; PMID:2680424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Rowat AC, Jaalouk DE, Zwerger M, Ung WL, Eydelnant IA, Olins DE, Olins AL, Herrmann H, Weitz DA, Lammerding J. Nuclear envelope composition determines the ability of neutrophil-type cells to passage through micron-scale constrictions. J Biol Chem 2013; 288:8610-8; PMID:23355469; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M112.441535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Lautscham LA, Kammerer C, Lange JR, Kolb T, Mark C, Schilling A, Strissel PL, Strick R, Gluth C, Rowat AC, et al.. Migration in Confined 3D Environments Is Determined by a Combination of Adhesiveness, Nuclear Volume, Contractility, and Cell Stiffness. Biophys J 2015; 109:900-13; PMID:26331248; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.07.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Booth-Gauthier EA, Du V, Ghibaudo M, Rape AD, Dahl KN, Ladoux B. Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome alters nuclear shape and reduces cell motility in three dimensional model substrates. Integr Biol (Camb) 2013; 5:569-77; PMID:23370891; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1039/c3ib20231c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Davidson PM, Denais C, Bakshi MC, Lammerding J. Nuclear deformability constitutes a rate-limiting step during cell migration in 3-D environments. Cell Mol Bioeng 2014; 7:293-306; PMID:25436017; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s12195-014-0342-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Mitchell MJ, Denais C, Chan MF, Wang Z, Lammerding J, King MR. Lamin A/C deficiency reduces circulating tumor cell resistance to fluid shear stress. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2015; 309:C736-46; PMID:26447202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].McGregor AL, Hsia C-R, Lammerding J. Squish and squeeze — the nucleus as a physical barrier during migration in confined environments. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2016; 40:32-40; PMID:26895141; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ceb.2016.01.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Shimi T, Pfleghaar K, Kojima S, Pack CG, Solovei I, Goldman AE, Adam SA, Shumaker DK, Kinjo M, Cremer T, et al.. The A- and B-type nuclear lamin networks: microdomains involved in chromatin organization and transcription. Genes Dev 2008; 22:3409-21; PMID:19141474; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.1735208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Maeshima K, Yahata K, Sasaki Y, Nakatomi R, Tachibana T, Hashikawa T, Imamoto F, Imamoto N. Cell-cycle-dependent dynamics of nuclear pores: pore-free islands and lamins. J Cell Sci 2006; 119:4442-51; PMID:17074834; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/jcs.03207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Barascu A, Le Chalony C, Pennarun G, Genet D, Imam N, Lopez B, Bertrand P. Oxidative stress induces an ATM-independent senescence pathway through p38 MAPK-mediated lamin B1 accumulation. EMBO J 2012; 31:1080-94; PMID:22246186; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/emboj.2011.492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Freund A, Laberge RM, Demaria M, Campisi J. Lamin B1 loss is a senescence-associated biomarker. Mol Biol Cell 2012; 23:2066-75; PMID:22496421; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1091/mbc.E11-10-0884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Dreesen O, Chojnowski A, Ong PF, Zhao TY, Common JE, Lunny D, Lane EB, Lee SJ, Vardy LA, Stewart CL, et al.. Lamin B1 fluctuations have differential effects on cellular proliferation and senescence. J Cell Biol 2013; 200:605-17; PMID:23439683; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.201206121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Sadaie M, Salama R, Carroll T, Tomimatsu K, Chandra T, Young AR, Narita M, Perez-Mancera PA, Bennett DC, Chong H, et al.. Redistribution of the Lamin B1 genomic binding profile affects rearrangement of heterochromatic domains and SAHF formation during senescence. Genes Dev 2013; 27:1800-8; PMID:23964094; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.217-281.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Shah PP, Donahue G, Otte GL, Capell BC, Nelson DM, Cao K, Aggarwala V, Cruickshanks HA, Rai TS, McBryan T, et al.. Lamin B1 depletion in senescent cells triggers large-scale changes in gene expression and the chromatin landscape. Genes Dev 2013; 27:1787-99; PMID:23934658; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.223-834.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Sadaie M, Dillon C, Narita M, Young AR, Cairney CJ, Godwin LS, Torrance CJ, Bennett DC, Keith WN, Narita M. Cell-based screen for altered nuclear phenotypes reveals senescence progression in polyploid cells after Aurora kinase B inhibition. Mol Biol Cell 2015; 26:2971-85; PMID:26133385; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1091/mbc.E15-01-0003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Chow KH, Factor RE, Ullman KS. The nuclear envelope environment and its cancer connections. Nat Rev Cancer 2012; 12:196-209; PMID:22337151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Foster CR, Przyborski SA, Wilson RG, Hutchison CJ. Lamins as cancer biomarkers. Biochem Soc Trans 2010; 38:297-300; PMID:20074078; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1042/BST0380297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Sun S, Xu MZ, Poon RT, Day PJ, Luk JM. Circulating Lamin B1 (LMNB1) biomarker detects early stages of liver cancer in patients. J Proteome Res 2010; 9:70-8; PMID:19522540; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/pr9002118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Broers JL, Raymond Y, Rot MK, Kuijpers H, Wagenaar SS, Ramaekers FC. Nuclear A-type lamins are differentially expressed in human lung cancer subtypes. Am J Pathol 1993; 143:211-20; PMID:8391215 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Kaufmann SH, Mabry M, Jasti R, Shaper JH. Differential expression of nuclear envelope lamins A and C in human lung cancer cell lines. Cancer Res 1991; 51:581-6; PMID:1985776 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].de Las Heras JI, Batrakou DG, Schirmer EC. Cancer biology and the nuclear envelope: A convoluted relationship. Semin Cancer Biol 2013; 23:125-37; PMID:22311402; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.semcancer.2012.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Levy DL, Heald R. Nuclear size is regulated by importin alpha and Ntf2 in Xenopus. Cell 2010; 143:288-98; PMID:20946986; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.201-0.09.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Newport JW, Wilson KL, Dunphy WG. A lamin-independent pathway for nuclear envelope assembly. J Cell Biol 1990; 111:2247-59; PMID:2277059; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.111.6.2247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Jenkins H, Holman T, Lyon C, Lane B, Stick R, Hutchison C. Nuclei that lack a lamina accumulate karyophilic proteins and assemble a nuclear matrix. J Cell Sci 1993; 106 (Pt 1):275-85; PMID:7903671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Nieuwkoop PD, Faber J. Normal Table of Xenopus laevis (Daudin). Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Company, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- [71].Jevtic P, Levy DL. Nuclear size scaling during Xenopus early development contributes to midblastula transition timing. Curr Biol 2015; 25:45-52; PMID:25484296; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cub.2014.10.051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Gerhart JC. Mechanisms regulating pattern formation in the amphibian egg and early embryo In: Goldberger RF, ed. Biological Regulation and Development. New York: Plenum, 1980:133-316. [Google Scholar]

- [73].Meyerzon M, Gao Z, Liu J, Wu JC, Malone CJ, Starr DA. Centrosome attachment to the C. elegans male pronucleus is dependent on the surface area of the nuclear envelope. Dev Biol 2009; 327:433-46; PMID:19162001; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.12.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Ladouceur AM, Dorn JF, Maddox PS. Mitotic chromosome length scales in response to both cell and nuclear size. J Cell Biol 2015; 209:645-52; PMID:26033258; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.201502092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Edens LJ, Levy DL. cPKC regulates interphase nuclear size during Xenopus development. J Cell Biol 2014; 206:473-83; PMID:25135933; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.201406004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Edens LJ, Levy DL. A cell-free assay using Xenopus laevis embryo extracts to study mechanisms of nuclear size regulation. Journal of Visualized Experiments 2016; In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Anderson DJ, Hetzer MW. Nuclear envelope formation by chromatin-mediated reorganization of the endoplasmic reticulum. Nat Cell Biol 2007; 9:1160-6; PMID:17828249; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb1636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Olmos Y, Hodgson L, Mantell J, Verkade P, Carlton JG. ESCRT-III controls nuclear envelope reformation. Nature 2015; 522:236-9; PMID:26040713; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature14503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Vietri M, Schink KO, Campsteijn C, Wegner CS, Schultz SW, Christ L, Thoresen SB, Brech A, Raiborg C, Stenmark H. Spastin and ESCRT-III coordinate mitotic spindle disassembly and nuclear envelope sealing. Nature 2015; 522:231-5; PMID:26040712; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature14408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Anderson DJ, Vargas JD, Hsiao JP, Hetzer MW. Recruitment of functionally distinct membrane proteins to chromatin mediates nuclear envelope formation in vivo. J Cell Biol 2009; 186:183-91; PMID:19620630; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200901106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Hetzer M, Meyer HH, Walther TC, Bilbao-Cortes D, Warren G, Mattaj IW. Distinct AAA-ATPase p97 complexes function in discrete steps of nuclear assembly. Nat Cell Biol 2001; 3:1086-91; PMID:11781570; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb1201-1086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Mochida K, Oikawa Y, Kimura Y, Kirisako H, Hirano H, Ohsumi Y, Nakatogawa H. Receptor-mediated selective autophagy degrades the endoplasmic reticulum and the nucleus. Nature 2015; 522:359-62; PMID:26040717; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature14506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].West M, Zurek N, Hoenger A, Voeltz GK. A 3D analysis of yeast ER structure reveals how ER domains are organized by membrane curvature. J Cell Biol 2011; 193:333-46; PMID:21502358; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.201011039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Voeltz GK, Prinz WA, Shibata Y, Rist JM, Rapoport TA. A class of membrane proteins shaping the tubular endoplasmic reticulum. Cell 2006; 124:573-86; PMID:16469703; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.20-05.11.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Yang YS, Strittmatter SM. The reticulons: a family of proteins with diverse functions. Genome Biol 2007; 8:234; PMID:18177508; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/gb-2007-8-12-234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Anderson DJ, Hetzer MW. Reshaping of the endoplasmic reticulum limits the rate for nuclear envelope formation. J Cell Biol 2008; 182:911-24; PMID:18779370; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200805140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Webster M, Witkin KL, Cohen-Fix O. Sizing up the nucleus: nuclear shape, size and nuclear-envelope assembly. J Cell Sci 2009; 122:1477-86; PMID:19420234; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/jcs.037333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Shibata Y, Shemesh T, Prinz WA, Palazzo AF, Kozlov MM, Rapoport TA. Mechanisms determining the morphology of the peripheral ER. Cell 2010; 143:774-88; PMID:21111237; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Orso G, Pendin D, Liu S, Tosetto J, Moss TJ, Faust JE, Micaroni M, Egorova A, Martinuzzi A, McNew JA, et al.. Homotypic fusion of ER membranes requires the dynamin-like GTPase atlastin. Nature 2009; 460:978-83; PMID:19633650; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature08280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Hu J, Shibata Y, Zhu PP, Voss C, Rismanchi N, Prinz WA, Rapoport TA, Blackstone C. A class of dynamin-like GTPases involved in the generation of the tubular ER network. Cell 2009; 138:549-61; PMID:19665976; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Chen S, Desai T, McNew JA, Gerard P, Novick PJ, Ferro-Novick S. Lunapark stabilizes nascent three-way junctions in the endoplasmic reticulum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015; 112:418-23; PMID:25548161; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1423026112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Golden A, Liu J, Cohen-Fix O. Inactivation of the C. elegans lipin homolog leads to ER disorganization and to defects in the breakdown and reassembly of the nuclear envelope. J Cell Sci 2009; 122:1970-8; PMID:19494126; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/jcs.044743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Campbell JL, Lorenz A, Witkin KL, Hays T, Loidl J, Cohen-Fix O. Yeast nuclear envelope subdomains with distinct abilities to resist membrane expansion. Mol Biol Cell 2006; 17:1768-78; PMID:16467382; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1091/mbc.E05-09-0839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Gorjanacz M, Mattaj IW. Lipin is required for efficient breakdown of the nuclear envelope in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Cell Sci 2009; 122:1963-9; PMID:19494125; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/jcs.044750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Hennekes H, Peter M, Weber K, Nigg EA. Phosphorylation on protein kinase C sites inhibits nuclear import of lamin B2. J Cell Biol 1993; 120:1293-304; PMID:8449977; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.120.6.1293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Kill IR, Hutchison CJ. S-phase phosphorylation of lamin B2. FEBS Lett 1995; 377:26-30; PMID:8543011; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01302-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Hatch E, Hetzer M. Breaching the nuclear envelope in development and disease. J Cell Biol 2014; 205:133-41; PMID:24751535; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.2014-02003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Bjorling E, Lindskog C, Oksvold P, Linne J, Kampf C, Hober S, Uhlen M, Ponten F. A web-based tool for in silico biomarker discovery based on tissue-specific protein profiles in normal and cancer tissues. Mol Cell Proteomics 2008; 7:825-44; PMID:17913849; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/mcp.M700411-MCP200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Rahbari R, Kitano M, Zhang L, Bommareddi S, Kebebew E. RTN4IP1 is down-regulated in thyroid cancer and has tumor-suppressive function. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013; 98:E446-54; PMID:23393170; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1210/jc.2012-3180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Jevtic P, Levy DL. Mechanisms of nuclear size regulation in model systems and cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol 2014; 773:537-69; PMID:24563365; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/978-1-4899-8032-8_25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Shirahata M, Oba S, Iwao-Koizumi K, Saito S, Ueno N, Oda M, Hashimoto N, Ishii S, Takahashi JA, Kato K. Using gene expression profiling to identify a prognostic molecular spectrum in gliomas. Cancer Sci 2009; 100:165-72; PMID:19038000; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.01002.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Van de Velde HJ, Senden NH, Roskams TA, Broers JL, Ramaekers FC, Roebroek AJ, Van de Ven WJ. NSP-encoded reticulons are neuroendocrine markers of a novel category in human lung cancer diagnosis. Cancer Res 1994; 54:4769-76; PMID:8062278 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Senden N, Linnoila I, Timmer E, van de Velde H, Roebroek A, Van de Ven W, Broers J, Ramaekers F. Neuroendocrine-specific protein (NSP)-reticulons as independent markers for non-small cell lung cancer with neuroendocrine differentiation. An in vitro histochemical study. Histochem Cell Biol 1997; 108:155-65; PMID:9272435; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s004180050157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Marshall WF. Cellular length control systems. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2004; 20:677-93; PMID:15473856; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.012103.094437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Jorgensen P, Edgington NP, Schneider BL, Rupes I, Tyers M, Futcher B. The size of the nucleus increases as yeast cells grow. Mol Biol Cell 2007; 18:3523-32; PMID:17596521; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1091/mbc.E06-10-0973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Neumann FR, Nurse P. Nuclear size control in fission yeast. J Cell Biol 2007; 179:593-600; PMID:17998401; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200708054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Weber SC, Brangwynne CP. Inverse size scaling of the nucleolus by a concentration-dependent phase transition. Curr Biol 2015; 25:641-6; PMID:25702583; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cub.2015.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Brangwynne CP. Phase transitions and size scaling of membrane-less organelles. J Cell Biol 2013; 203:875-81; PMID:24368804; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.2013-08087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Levy DL, Heald R. Mechanisms of intracellular scaling. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2012; 28:113-35; PMID:22804576; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Decker M, Jaensch S, Pozniakovsky A, Zinke A, O'Connell KF, Zachariae W, Myers E, Hyman AA. Limiting amounts of centrosome material set centrosome size in C. elegans embryos. Curr Biol 2011; 21:1259-67; PMID:21802300; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cub.2011.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Rafelski SM, Viana MP, Zhang Y, Chan YH, Thorn KS, Yam P, Fung JC, Li H, Costa Lda F, Marshall WF. Mitochondrial network size scaling in budding yeast. Science 2012; 338:822-4; PMID:23139336; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1225720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Hazel J, Krutkramelis K, Mooney P, Tomschik M, Gerow K, Oakey J, Gatlin JC. Changes in Cytoplasmic Volume Are Sufficient to Drive Spindle Scaling. Science (New York, NY) 2013; 342:853-6; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1243110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Good MC, Vahey MD, Skandarajah A, Fletcher DA, Heald R. Cytoplasmic volume modulates spindle size during embryogenesis. Science (New York, NY) 2013; 342:856-60; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1243147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Wuhr M, Chen Y, Dumont S, Groen AC, Needleman DJ, Salic A, Mitchison TJ. Evidence for an upper limit to mitotic spindle length. Curr Biol 2008; 18:1256-61; PMID:18718761; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cub.2008.07.092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Loughlin R, Heald R, Nedelec F. A computational model predicts Xenopus meiotic spindle organization. J Cell Biol 2010; 191:1239-49; PMID:21173114; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.201006076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Reber SB, Baumgart J, Widlund PO, Pozniakovsky A, Howard J, Hyman AA, Julicher F. XMAP215 activity sets spindle length by controlling the total mass of spindle microtubules. Nat Cell Biol 2013; 15:1116-22; PMID:23974040; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb2834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].Loughlin R, Wilbur JD, McNally FJ, Nedelec FJ, Heald R. Katanin contributes to interspecies spindle length scaling in Xenopus. Cell 2011; 147:1397-407; PMID:22153081; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].Wilbur JD, Heald R. Mitotic spindle scaling during Xenopus development by kif2a and importin alpha. eLife 2013; 2:e00290; PMID:23425906; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.7554/eLife.00290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [119].Chan YH, Marshall WF. Scaling properties of cell and organelle size. Organogenesis 2010; 6:88-96; PMID:20885855; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/org.6.2.11464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [120].Arata Y, Takagi H, Sako Y, Sawa H. Power law relationship between cell cycle duration and cell volume in the early embryonic development of Caenorhabditis elegans. Front Physiol 2014; 5:529; PMID:25674063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [121].Newport J, Kirschner M. A major developmental transition in early Xenopus embryos: II. Control of the onset of transcription. Cell 1982; 30:687-96; PMID:7139712; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90273-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [122].Newport J, Kirschner M. A major developmental transition in early Xenopus embryos: I. characterization and timing of cellular changes at the midblastula stage. Cell 1982; 30:675-86; PMID:6183003; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90272-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [123].Clute P, Masui Y. Regulation of the appearance of division asynchrony and microtubule-dependent chromosome cycles in Xenopus laevis embryos. Dev Biol 1995; 171:273-85; PMID:7556912; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1006/dbio.1995.1280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [124].Amodeo AA, Skotheim JM. Cell-Size Control. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2015:193-208. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a019083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [125].Amodeo AA, Jukam D, Straight AF, Skotheim JM. Histone titration against the genome sets the DNA-to-cytoplasm threshold for the Xenopus midblastula transition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015; 112:E1086-95; PMID:25713373; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1413990112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [126].Murphy CM, Michael WM. Control of DNA replication by the nucleus/cytoplasm ratio in Xenopus. J Biol Chem 2013; 288:29382-93; PMID:23986447; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M113.499012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [127].Collart C, Allen GE, Bradshaw CR, Smith JC, Zegerman P. Titration of four replication factors is essential for the Xenopus laevis midblastula transition. Science 2013; 341:893-6; PMID:23907533; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1241530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [128].Kermi C, Prieto S, van der Laan S, Tsanov N, Recolin B, Uro-Coste E, Delisle MB, Maiorano D. RAD18 Is a Maternal Limiting Factor Silencing the UV-Dependent DNA Damage Checkpoint in Xenopus Embryos. Dev Cell 2015; 34:364-72; PMID:26212134; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [129].Xue JZ, Woo EM, Postow L, Chait BT, Funabiki H. Chromatin-bound Xenopus dppa2 shapes the nucleus by locally inhibiting microtubule assembly. Dev Cell 2013; 27:47-59; PMID:24075807; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [130].Schlaitz AL, Thompson J, Wong CC, Yates JR 3rd, Heald R. REEP3/4 ensure endoplasmic reticulum clearance from metaphase chromatin and proper nuclear envelope architecture. Dev Cell 2013; 26:315-23; PMID:23911198; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.06.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]