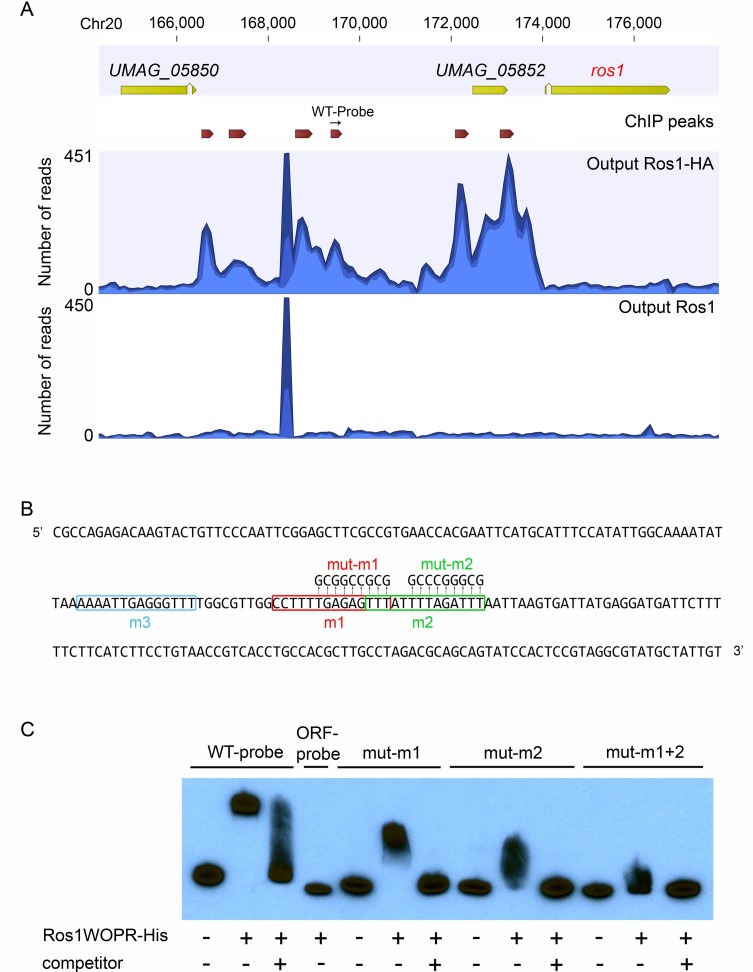

Fig 9. Ros1 binds to the ros1 promoter region.

(A) The graph generated with the CLC Genomics Workbench 7.5 software (CLC bio) shows the ChIP-seq read distribution in the genomic region containing ros1 in output DNA from the sample where maize was infected with FB1Δros1-Ros1HA x FB2Δros1-Ros1HA (Output Ros1HA) and in the control sample where the infection was done with FB1Δros1-Ros1 x FB2Δros1-Ros1 (output Ros1) Open reading frames are represented by yellow arrows. Peaks with significant peak shape scores are indicated in the ChIP peaks lane by dark red arrows. The location of the fragment (WT-probe) used as a probe for EMSA is indicated by a black arrow. (B) Sequence of the probe fragment used for EMSA assays. Putative binding sites (m1, m2 and m3) for Ros1 are boxed and mutations introduced in the respective sites are indicated (mut-m1, mut-m2). (C) In vitro binding of Ros1WOPR-His to the ros1 promoter. Ros1WOPR-His expressed and purified from E. coli was used in EMSA assays with the probe shown in B (WT-probe). When incubated with Ros1WOPR-His, the WT-probe was shifted and this could be competed by addition of a non-labeled WT-probe (competitor). Ros1WOPR-His did not bind a probe of the same length corresponding to a part of the ros1 coding sequence (ORF-probe). Probes mut-m1 and mut-m2 harboring mutations in motifs 1 and 2 are also bound by Ros1WOPR-His, but the interaction results in a less pronounced shift than observed for the WT-probe and an even smaller shift when both motifs are mutated (mut-m1+2). Binding to mutated probes could also be efficiently competed by adding a non-labeled WT-probe.