Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to systematically evaluate the sagittal kinematic and kinetic gait patterns in patients in this early post-operative period, to describe them and to better understand the deficiencies in that gait pattern that may help to develop targeted rehabilitation strategies.

Methods

This study evaluated early gait patterns in 10 patients with isolated unilateral hip osteoarthritis who were post-operative for total hip replacement. Kinetic and kinematic assessments – focusing on sagittal plane abnormalities – were performed at 2 weeks pre-operatively and 8 weeks post-operatively.

Results

Our results demonstrated that while clinical scoring for pain and functional ability significantly improved post-operatively, as did clinical assessment of range of motion passively, this did not translate to the degree of dynamic improvement in gait. Step length and stride length did not improve significantly. Lack of hip extension in terminal stance associated with excessive anterior pelvic tilt persisted and was associated with a worsening in hip extensor power post-operatively.

Conclusion

Based on our results, post-operative rehabilitation programmes should include extensor muscle exercises to increase power and to retain the operative gain in passive range of motion, which would help to improve gait patterns.

Keywords: Gait analysis, Orthopaedics, Hip replacement, Post-operative

1. Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) of the hip causes alteration in normal kinematic patterns – particularly in the sagittal plane.1, 6, 7, 9 This may be primarily due to pain, a decreased range of motion because of contractures or a combination of both. Total hip replacement surgery (THR) is one of the most successful surgeries, and provides symptomatic relief for patients with painful osteoarthritis.2, 3, 4 Despite this huge gain in functional ability and a subjective improvement in walking ability, gait patterns in patients undergoing THR improve, but rarely achieve normality.5, 6, 7, 10 Many gait analysis studies have shown that gait patterns remain abnormal in the long term and are comparable to pre-operative gait.9, 12, 17, 18, 19 Foucher et al. demonstrated that pre-operative gait parameters were strong predictors of some post-operative gait parameters.8 Range of motion was improved following THR, but in many cases remained less than normal. It is important to note that hip flexion contractures, with resultant loss of hip extension, have been shown to recur up to 1 year after total hip replacement, and is probably due to a combination of factors, e.g. persistent muscle weakness, scar tissue formation and learned gait patterns though the exact pathogenesis is unknown.10, 11, 29 Recent outcome studies have shown that post-operative range of hip motion correlates strongly with functional outcome.35, 36 The purpose of this study was to systematically evaluate the sagittal kinematic and kinetic gait patterns in patients in this early post-operative period, to describe them and to better understand the deficiencies in that gait pattern that may help to develop targeted rehabilitation strategies.

2. Methods

2.1. Patient selection and procedure

Inclusion criteria for the study were patients with isolated unilateral painful hip osteoarthritis, with no significant medical problems (ASA grade I & II) who were awaiting a total hip replacement in Adelaide and Meath, incorporating the National Children's Hospital (AMNCH) Tallaght.32, 34 Exclusion criteria included patients with: contralateral hip pathology, contralateral hip replacement, knee pathology, neurological impairment of the lower limbs, leg length discrepancy in a lower limb segment other than the pathological hip and fixed spinal deformity, as these factors would all have an affect on gait independent of hip pathology. Case notes for all patients on the AMNCH waiting list were reviewed and all patients who met the inclusion/exclusion criteria were invited to participate. A cohort of ten patients were identified and contacted. Participation was voluntary, and informed consent was obtained in each case.

Patients were assessed 2 weeks pre-operatively and 8 weeks post-operatively over a 4-month period. A thorough clinical examination was conducted, using a goniometer to determine joint range of motion for all lower limb joints and presence of contractures. Manual muscle strength testing was also tested and documented (strength classified on the Medical Research Council Scale, graded 0 = no contraction to 5 = normal).33 Radiological examination included AP pelvis X-ray to determine grade of OA using Kellgren and Lawrence scale, and CT scanography to accurately measure for any leg length discrepancy.12 Self-assessment questionnaires were completed to give an objective measure of function – SF-36v2 and Harris Hip Score (HHS).34

Three-dimensional lower limb gait analysis was performed in the Gait Laboratory Central Remedial Clinic (CRC), Clontarf using 3 CODA MPX30 motion analysers (Charnwood Dynamics Limited, Leicestershire, England). Twenty-four surface mounts, consisting of markers in each three-dimensional plane (coded LEDs) were applied to the bony sites of each of the lower limbs, according to the Bell Hip model, which allows markers to be seen laterally.13 Markers were applied by the same investigator pre- and post-operatively. The pre-calibrated system captures the infrared light signal sequence from these markers, at a frequency of 200 Hz as the patient walks on a 20 m walkway. Patients were requested to refrain from using analgesics on the day of the assessment. Static and dynamic foot forces were recorded using Kistler piezo-electric footplates, embedded in the walkway (Kistler Instruments Ltd.) and subsequent joint forces and moments were calculated using inverse dynamic equations. Kinematic and kinetic patterns of the pelvis, hip, knee and ankle joints of the lower limbs were therefore assessed. Measuring three successive gait cycles to improve the accuracy and objectivity of the measurements by ensuring reliability and determining repeatability for each patients specific gait pattern minimized variability in the group. Data from a single representative cycle was retrieved for each patient and results produced were intra-subject ensemble averages.

All patients had THR surgery performed through an anterolateral approach with half receiving a cemented Charnley THR (DePuy™) and half an uncemented Plasma cup/Bicontact stems (Braun Aesculap™).

Post-operatively, the patients received focused orthopaedic physiotherapist and were also instructed on a home exercise programme to include joint ROM exercises and abductor muscle strengthening. The patients were reassessed clinically and radiologically and self-assessment forms were repeated. Gait analysis was repeated and the results compared to assess the changes in the kinematic and kinetic patterns following total hip replacement. The results were further compared to a database of age- and sex-matched controls.

2.2. Statistical analysis

Paired t-tests were used to test for differences between pre-operative and post-operative variables for the affected and unaffected limbs. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS1 13.0. P values <0.05 were considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Patient demographics

The mean age was 55.4 (43–71), M:F 1:1 and mean BMI 27.1 (range, 22.7–31.8). Nine out of ten patients had moderate/severe OA in their affected hip (Table 1). The ten patients fully completed all aspects of the study, and there were no post-operative complications that may have affected the results. Repeat post-operative assessments were performed at 8 weeks, and all patients were independently mobile at that stage. Post-operative leg length discrepancy ranged from −26 mm to +5 mm, with a mean of −2.5 mm.

Table 1.

Radiological grade of OA.

| Kellgren & Lawrence grade | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| No of patients | 1 | 1 | 6 | 2 |

3.2. Functional outcome scoring

Table 2 shows the functional scores. There was a statistically significant improvement in mean functional outcome based on physical component of SF-36v2 scoring, and for the components of pain, function and range on motion, but not deformity on Harris Hip Scoring.

Table 2.

Mean functional scores.

| Pre-operative mean score | Post-operative mean score | Change in mean score | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-36 v2 – PCSa | 35.05 | 50.06 | 15.01 | <.001 |

| SF-36 v2 – MCSb | 49.7 | 55.67 | 5.97 | .10 |

| Harris Hip Score | 60.71 | 89.9 | 29.2 | <.001 |

| Pain | 23 | 43.2 | 20.2 | <.001 |

| Function | 31.5 | 38.5 | 7 | .002 |

| Deformity | 2.8 | 3.6 | 0.8 | .17 |

| Range of motion | 3.31 | 4.58 | 1.27 | .002 |

Physical component score.

Mental component score.

3.3. Clinical range of motion

Pre-operatively, there was marked decreased range of motion in the affected hip of all patients (Table 3). Nine of the ten patients had a fixed flexion deformity (FFD) contracture pre-operatively. Mean −15° (−4° to −30°). In all patients post-operatively there was no fixed flexion contracture apparent on clinical examination, and all could achieve active hip extension to neutral, at least (Table 3). This improvement was statistically significant (p = 0.0001).

Table 3.

Analysis of range of motion results affected hip.

| Pre-operative mean | Post-operative mean | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hip extension (°) | −15.0 | 1.80 | <.001 |

| Hip flexion (°) | 82.7 | 94.3 | .002 |

| Hip internal rotation in flexion (°) | 1.7 | 10.6 | <.001 |

| Hip external rotation in flexion (°) | 6.7 | 21.6 | <.001 |

| Hip abduction (°) | 14.71 | 19.85 | .05 |

| Hip adduction (°) | 6.01 | 15.20 | <.001 |

P < .05 with 95% CI.

3.4. Temperospatial parameters

Pre-operatively the walking velocity, cadence and step length were all reduced, compared to normal ranges. Though there was improvement in all variables post-operatively, this was not statistically significant (Table 4). Step length can vary between affected and unaffected side, i.e. with an antalgic gait. However, symmetry ratio of step length between affected and unaffected side showed no differences pre- or post-operatively (Table 5) though the percentage stance duration was significantly higher for the unaffected limb pre-operatively (63.7 versus 60.42, p = 0.022). There was modest improvement in single limb support post-operatively on the affected side (36.3% versus 37.76%), but there was still a statistically significant difference between the affected and unaffected limb for percentage stance (59.84% versus 62.24%, p = 0.016), and percentage single limb support (37.76% versus 40.16%, p = 0.016), indicating residual asymmetry between the limbs despite clinical improvement in pain.

Table 4.

Analysis of temperospatial parameters affected hip.

| Normala | Pre-operative mean | Post-operative mean | Change in mean score | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gait cycle time (s) | 1.01 | 1.12 | 1.07 | −0.05 | .24 |

| Cadence (Step/min) | 119.9 | 108.38 | 112.07 | 3.7 | .31 |

| Step length (m) | 0.73 | 0.586 | 0.614 | 0.028 | .10 |

| Stride length (m) | 1.46 | 1.175 | 1.237 | 0.062 | .07 |

| Walking velocity (m/s) | 1.46 | 1.091 | 1.171 | 0.08 | .12 |

| Percentage stance | 59.9 | 60.42 | 59.84 | −0.58 | .43 |

| Percentage single limb support | 40.2 | 36.3 | 37.76 | 1.46 | .27 |

P < .05 with 95% CI.

CRC Laboratory normal.

Table 5.

Comparative analysis of temperospatial parameters.

| Pre-operative |

Post-operative |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affected side | Unaffected side | P value | Affected side | Unaffected side | P value | |

| Step length (m) | 0.586 | 0.590 | .76 | 0.614 | 0.62 | .70 |

| Percentage stance | 60.42 | 63.7 | .02 | 59.84 | 62.24 | .02 |

| Percentage single limb support | 36.3 | 39.67 | .02 | 37.76 | 40.16 | .02 |

P < .05 with 95% CI.

3.5. Gait kinematics & kinetics

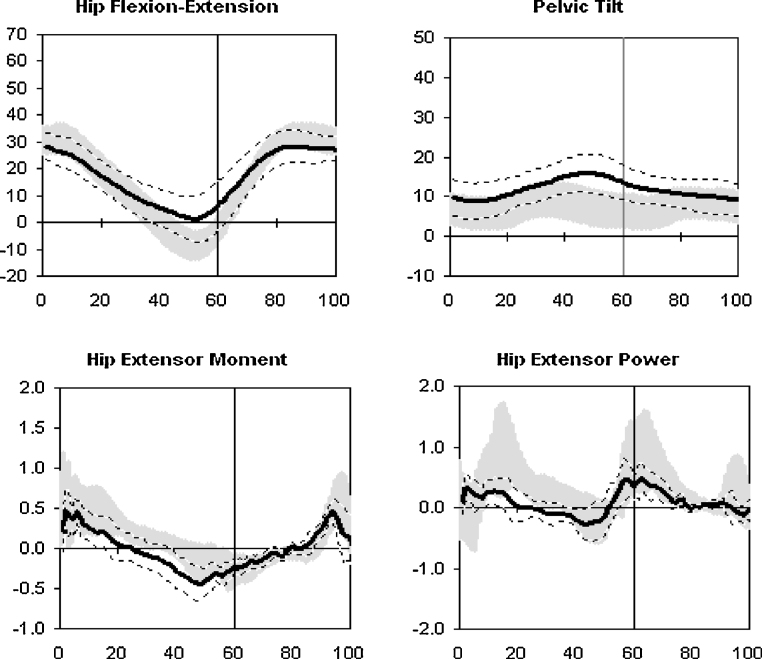

The key kinematic and kinetic data is summarized in Table 6, and relevant graphs are shown in Fig. 1, Fig. 2. The most significant pre-operative finding was lack of hip extension and excessive anterior pelvic tilt seen in terminal stance and pre-swing phases. While there was improvement post-operatively in sagittal hip kinematics in terms of hip extension and hip range of motion, there was still a relative lack of hip extension in terminal stance (0.49°), despite a clinical improvement in passive hip extension and resolution of the FFD. Excessive anterior tilt also improved post-operatively but was still abnormal (16.62°) – reflecting the persistent lack of hip extension post-operatively. Kinetic assessment showed that while hip extension improved overall post-operatively, hip extensor power did not improve. In fact, hip extensor power dis-improved during early stance compared to pre-operative measures (Fig. 1, Fig. 2).

Table 6.

Summary gait kinematic and kinetic parameters pre- and post-operatively affected hip.

| Normal | Pre operative mean | Post operative mean | Change in mean | P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum anterior pelvic tilt (°) | 9.21 | 20.08 | 16.62 | −3.83 | .07 |

| Minimum anterior pelvic tilt (°) | 4.4 | 11 | 7.75 | −3.25 | .12 |

| Pelvic tilt range | 4.8 | 9.08 | 8.50 | −0.58 | .68 |

| Max hip flexion (°) | 33.4 | 34.85 | 29.21 | −5.64 | .08 |

| Max hip extension in stance (°) | 8.95 | −13.21 | −0.49 | 12.72 | <.001a |

| Hip range | 42.4 | 21.63 | 29.42 | 7.79 | <.001a |

| Max hip extensor power (W/kg) | 0.96 | 0.4761 | 0.32 | −0.14 | .3 |

| Max hip flexor power (W/kg) | 0.92 | 0.32 | 0.47 | 0.15 | .1 |

| Knee flexion (°) | 64.6 | 55.55 | 53.31 | −2.24 | .59 |

| Knee extension (°) | 0.84 | −0.29 | 4.34 | −4.62 | <.001a |

| Knee range | 65.4 | 55.26 | 57.65 | 2.38 | .46 |

| Ankle dorsiflexion (°) | 13.87 | 14.45 | 14.09 | −0.36 | .9 |

| Ankle plantarflexion (°) | 24.25 | 16.35 | 16.25 | 0.1 | .92 |

| Ankle range | 38.12 | 30.8 | 30.35 | −0.55 | .88 |

The italic values represent the numerical difference between the pre- and post-operative mean.

P-value is pre- compared to post-operative results.

Significant difference <.05 between pre- and post-operative mean.

Fig. 1.

Ensemble averages for pre-operative sagittal hip and pelvis kinematics and hip extensor moment and power in affected hip. — Ensemble averages. --- Max/mon for dataset.  CRC Laboratory normal database results.

CRC Laboratory normal database results.

Fig. 2.

Ensemble averages for post-operative sagittal hip and pelvis kinematic and hip extensor moment and power in affected hip. — Ensemble averages. --- Max/mon for dataset.  CRC Laboratory normal database results. Ensemble average kinematic gait cycle overlaid on normal band. Horizontal axis: percentage of gait cycle. 0 = initial contact; 0–60 = stance phase; 60 = push-off; 60–100 = swing phase.

CRC Laboratory normal database results. Ensemble average kinematic gait cycle overlaid on normal band. Horizontal axis: percentage of gait cycle. 0 = initial contact; 0–60 = stance phase; 60 = push-off; 60–100 = swing phase.

4. Discussion

Many studies have evaluated and described the persisting abnormalities in gait patterns at up to two years post-operatively. The purpose of this study was to evaluate gait patterns and muscle function in the very early post-operative period in an attempt to compare clinical assessment with objective gait analysis parameters. Eight weeks were chosen as this was the earliest period that patients were likely to be walking without the use of crutches or post-operative analgesics, which could have altered results.

This study demonstrated a clinical improvement in range of motion in the affected hip in all planes eight weeks post-operatively, but this improvement had not carried over into walking ability. All patients improved subjectively and objectively based on SF-36v2 and HHS. Clinically, eight out of ten patients post-operatively had complete elimination of pain, and a statistically significant improvement in extension of the affected hip, yet the abnormality of lack of hip extension persisted post-operatively during walking. This was associated with an increase in anterior pelvic tilt.

In an antalgic gait, the patient classically tries to minimize the amount of weight applied to the painful hip and the amount of time that weight is applied. The result is a limp, a decreased single support time for the affected limb, a shortened step length for the contralateral limb and an increased double support time. Calve et al. proposed that this mechanism avoided stretching the joint capsule and thus prevented pain.14 In keeping with other studies of early gait following THR, this lack of terminal hip extension in late stance was associated with a decrease in hip extensor power and flexor moments of force and a decrease in the energy developed at the hip in the sagittal plane during push-off despite subjective improvement in symptoms.10, 11, 22, 26, 27, 29, 30 Though this may be a learned protective mechanism of the hip, it implies that pain is not the only factor affecting extension ability. The fact that hip extensor power actually decreased post-operatively despite improvement in both clinical range of motion and pain is important as it is potentially overlooked during routine post-operative assessment. Many physiotherapy rehabilitation programmes focus on coronal muscle strengthening i.e. abductor function but do not assess sagittal range and strength. Hip flexion contractures have been shown to recur up to 1 year after surgery and are probably due to a combination of factors e.g. persistent muscle weakness, learned gait patterns and scar tissue formation etc.10, 11, 21, 29 Our study patients demonstrated a persistent lack of hip extension during dynamic gait coupled with worsened hip extensor power post-operatively and we suggest this may be a possible the mechanism by which these contractures recur.

Our findings also reflect those of other studies in terms of lack of hip extension. Perron et al. suggested that the lack of hip extension was due to a decrease in step length, and was a learned pattern of gait, rather than due to a weakness of hip extensor muscles, but they did not assess clinical hip range of motion.1 Crosbie showed that lack of hip extension in walking correlated with lack of clinical range of motion and was speed-dependent.15 Hurwitz et al. showed decreased hip extensor moments associated with pain in patients with osteoarthritis rather than gait speed or dynamic hip range of motion. The authors felt that reduced moments reflect decreased muscle forces and decreased loads on the femoral head in the absence of increased antagonistic muscle activity and thus may be a pain-avoidance mechanism. However, they also demonstrated asymmetry in step length.30 In contrast, this study found that despite a failure to extend the hip on the affected side during walking, there was no difference in step length, and no difference in symmetry ratio between the affected and unaffected side pre- and post-operatively. Assessment of temperospatial parameters showed no statistical differences between the affected and unaffected side pre- or post-operatively for velocity, step length or cadence; however, the values were less compared to normative data.23, 24, 25, 27, 28 Though all parameters improved post-operatively, the differences were not statistically significant. This indicates a degree of symmetry between the limbs – however, there was a statistically significant difference in percentage stance time between the limbs both pre- and post-operatively. This residual antalgic gait may be an avoidance mechanism to reduce loading of the affected side, which persisted post-operatively despite resolution of pain and increased range of motion. Bennett et al. suggested that the range of motion in the unaffected hip may be effectively reduced to maintain symmetry and improve walking ability.16

Our patients were re-assessed at 8 weeks post-operatively, which is earlier than most studies. It has been shown that gait parameters improve for up to 1 year post-operatively, so it is not surprising that the abnormality of slower speed and decreased step length were still present post-operatively.17, 18, 23 McCrory et al. found that magnitude of peak hip forces was significantly less in the operated hip following THR, as was loading rate, impulse and stance time, i.e. patients “favoured” their affected limb by avoidance of weight acceptance, despite being pain-free, they displayed features of residual antalgic gait.20 They commented that the persisting asymmetric limb loading after THR may be beneficial in reducing the biomechanical load on the prosthesis.27 In contrast, Shakoor et al. suggested that biomechanical asymmetry post-operatively was disadvantageous. They demonstrated persistent asymmetry of limb loading in patients up to 2 years post THR – specifically noting a higher peak external knee adduction moment, and peak medial compartment moment in the contralateral knee, which persisted after surgery. They proposed this as the mechanism for which patients who undergo unilateral THR for OA are more likely to require a contralateral Total Knee Replacement in the future.31

5. Conclusion

We acknowledge that this study was limited by the small number of participants, which may have implications for the generalisability of our results. However, our group of participants was a uniform cohort with only single joint osteoarthritis, and we feel that the results obtained from this detailed study can be confidently attributed to the hip pathology. Our results suggest that gait patterns remain persistently abnormal post-operatively despite relatively normal clinical ranges of motion. This area requires further study to develop early post-operative rehabilitation programmes – focusing on hip extensor power and gait training rather than traditional hip range of motion and stretching.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of St James Hospital and the AMNCH, Tallaght.

Funding

There was no source of external funding.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Perron M., Malouin F., Moffet H., McFadyen B.J. Three dimensional gait analysis in women with a total hip arthroplasty. Clin Biomech 2000. 2000;5:504–515. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(00)00002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liang M., Cullen K., Larson M., Thompson M., Schwartz J., Fossel A. Cost effectiveness of total joint arthroplasty in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29:937–943. doi: 10.1002/art.1780290801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rissanen P., Aro S., Slatis P., Sintonen H., Paavolainen P. Health and quality of life before and after hip or knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1995;10:169–175. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(05)80123-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maloney W.J., Keeny J.A., Leg length discrepancy after total hip replacement J Arthroplasty. 2004;19(4 (Suppl. 1)):108–110. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2004.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loizeau J., Allard P., Duhaime M., Landjerit B. Bilateral gait patterns in subjects fitted with a total hip prosthesis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1995;76(June (6)):552–557. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(95)80510-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kyriazis V., Rigas C. Temporal gait analysis of hip osteoarthritic patients operated with cementless hip replacement. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2002;17(May (4)):318–321. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(02)00024-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wykman A., Olsson E. Walking ability after total hip replacement. A comparison of gait analysis in unilateral and bilateral cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1992;74(January (1)):53–56. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.74B1.1732266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foucher K.C., Hurwitz D.E., Soomekh D., Andriacchi T.P., Rosenberg A.G., Galante J.O. Factors influencing variation in gait adaptations after total hip arthroplasty. Gait Posture. 1998;7(March (2)):158–159. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanaka Y. Gait analysis of patients with osteoarthritis of the hip and those with total hip arthroplasty. J Jpn Orthop Assoc. 1993;67 1001±13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paul J.P. Gait analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1989;48:179–181. doi: 10.1136/ard.48.3.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paul J.P. Strength requirements for internal and external prostheses. J Biomech. 1999;32(April (4)):381–393. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(98)00190-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kellgren J.H., Lawrence J.S. Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1957;16:494–502. doi: 10.1136/ard.16.4.494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Newman C., Walsh M., O'Sullivan R. The characteristics of gait in Charcot–Marie-tooth disease – types I and II. Gait Posture. 2007;26(June (1)):120–127. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calve J., Galland M., DeCagney R. Pathogenesis of the limp due to coxalgia. J Bone Joint Surg. 1939;21:12–25. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crosbie J., Vachalathiti R. Synchrony of pelvic and hip joint motion during walking. Gait Posture. 1997;6:237–248. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bennett D., Humphreys L., O’Brien S., Kelly C., Orr J.F., Beverland D.E. Gait kinematics of age-stratified hip replacement patients – a large scale, long-term follow-up study. Gait Posture. 2008;28(August (2)):194–200. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murray M.P. Studies of the functional performance of patients before and after total joint replacement. Int J Rehabil Res. 1979;2(December (4)):543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wall J.C., Ashburn A., Klenerman L. Gait analysis in the assessment of functional performance before and after total hip replacement. J Biomed Eng. 1981;3(April (2)):121–127. doi: 10.1016/0141-5425(81)90004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murray M.P., Brewer B.J., Zuege R.C. Kinesiologic measurements of functional performance before and after McKee–Farrar total hip replacement. A study of thirty patients with rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, or avascular necrosis of the femoral head. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972;54(March (2)):237–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCrory J.L., White S.C., Lifeso R.M. Vertical ground reaction forces: objective measures of gait following hip arthroplasty. Gait Posture. 2001;14(October (2)):104–109. doi: 10.1016/s0966-6362(01)00140-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stansfield B.W., Nicol A.C. Hip joint contact forces in normal subjects and subjects with total hip prostheses: walking and stair and ramp negotiation. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2002;17(February (2)):130–139. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(01)00119-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mattsson E., Broström L.A., Linnarsson D. Walking efficiency after cemented and noncemented total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;(May (254)):170–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elble R.J., Thomas S.S., Higgins C., Colliver J. Stride-dependent changes in gait of older people. J Neurol. 1991;238(February (1)):1–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00319700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prince F., Corriveau H., Hébert R., Winter D.A. Gait in the elderly. Review article. Gait Posture. 1997;(5):128–135. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oberg T., Karsznia A., Oberg K. Basic gait parameters: reference data for normal subjects, 10–79 years of age. J Rehabil Res Dev. 1993;30(2):210–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Long W.T., Dorr L.D., Healy B., Perry J. Functional recovery of noncemented total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;(March (288)):73–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miki H., Sugano N., Hagio K. Recovery of walking speed and symmetrical movement of the pelvis and lower extremity joints after unilateral THA. J Biomech. 2004;37(April (4)):443–455. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murray M.P., Brewer B.J., Gore D.R., Zuege R.C. Kinesiology after McKee–Farrar total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg. 1975;57A 337±42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shimada T. Factors affecting appearance patterns of hip flexion contractures and their effects on postural and gait abnormalities. Kobe J Med Sci. 1996;42:271–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hurwitz D.E., Hulet C.H., Andriacchi T.P., Rosenberg A.G., Galante J.O. Gait compensations in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip and their relationship to pain and passive hip motion. J Orthop Res. 1997;15(July (4)):629–635. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100150421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shakoor N., Hurwitz D.E., Block J.A., Shott S., Case J.P. Asymmetric knee loading in advanced unilateral hip osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(June (6)):1556–1561. doi: 10.1002/art.11034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saklad M. Grading of patients for surgical procedures. Anesthesiology. 1941;2:281–284. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Medical Research Council . Her Majesty's Stationery Office; London: 1975. Aids to the investigation of the peripheral nerve system; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harris W.H. Traumatic arthritis of the hip after dislocation and acetabular fractures: treatment by mold arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg. 1969;51A:737–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davis K.E., Ritter M.A., Berend M.E., Meding J.B. The importance of range of motion after total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;465(December):180–184. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e31815c5a64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johansson H.R., Bergschmidt P., Skripitz R., Finze S., Bader R., Mittelmeier W. Impact of preoperative function on early postoperative outcome after total hip arthroplasty. J Orthopaed Surg. 2010;18(April (1)):6–10. doi: 10.1177/230949901001800102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]