Abstract

Background

Long term US trends in alcoholic beverage calorie intakes remain unexamined, particularly with respect to changes in population subgroup-specific patterns over time.

Objective

This study examines shifts in the consumption of alcoholic beverages, in total and by beverage type, on any given day among US adults in relation to socio-demographic characteristics.

Design

This study was a repeated cross-sectional analyses of data from the 1989–1991 and 1994–1996 Continuing Survey of Food Intakes by Individuals; 2003–2006 and 2009–2012 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys.

Participants/setting

Adults ≥19 years (N = 39,298); a subset of alcoholic beverage consumers (n = 7,081) were studied.

Statistical analyses performed

Survey weighted mean per capita per day intakes (among all participants, both consumers of alcoholic beverages and non-consumers) and contributions of beer, wine, and liquor/mixed drinks to total alcoholic beverage energy were determined. Multivariable regression models were used to examine trends in the proportion of alcoholic beverage consumers and the per consumer intakes (among consumers of alcoholic beverages only).

Results

Per capita intakes from alcoholic beverages increased from 49 kcal/cap/d in 1989–1991 to 109 kcal/cap/d in 2003–2006 (p<0.001). The proportion consuming alcoholic beverages on any given day increased significantly from 1989–1991 to 2009–2012 (p for overall increasing trend <0.0001) for most socio-demographic subgroups. Per consumer alcoholic beverage calories increased between 1989–1991 and 1994–1996 (p<0.05) for many subpopulations. Adults with <HS education were less likely to consume alcohol, yet had higher per consumer calorie intakes compared to adults with a college degree. Women and adults ≥ 60 years experienced a shift away from liquor/mixed drinks towards wine between 2003–2006 and 2009–2012. Beer contributed roughly 70% to total alcoholic beverage intake for less educated consumers across time.

Conclusions

These results indicate there has been an increase in the proportion of US adults who drink on any given day, and an increase in calories consumed from alcoholic beverages when drinking occurs.

Keywords: beer, wine, liquor, alcoholic beverages, calories

INTRODUCTION

Alcoholic beverages are among the top five contributors to total energy intake among United States (US) adults and are considered a source of calories that provides few nutrients. 1 Alcoholic beverage intake is linked with an array of dietary and health outcomes, including diet quality, energy intake, nutrient metabolism and body weight.2–4 Although findings are mixed, associations of alcoholic beverage consumption with nutrition-related health outcomes may differ by beverage type (i.e. beer, wine, liquor). 5–7 In 2013, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism suggested that future research should examine changes in alcohol consumption over time to examine differences within socio-demographic subgroups.3

There are a number of policies in effect in the US related to the purchase, use and sale of alcoholic beverages which may have influenced energy intake from alcoholic beverages from the 1980s onward. 8 The time period from 1989–2012 captures the consumption of alcohol beverages after the enactment of the National Minimum Drinking Age Act of 1984 (NMDAA) and during the first issue of sex specific drinking recommendations in the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA) in 1990. 1,9 Previous research utilizing dietary recall data from the USDA has shown that calories per capita per day (kcal/cap/d) consumed from alcoholic beverages, including beer, wine, and liquor and mixed drinks, have increased from 45 to 115 kcal/cap/d between 1965 and 2006. 10,11 Per capita per day estimates are means calculated from intakes of all respondents, including non-consumers and consumers of alcoholic beverages, on the day of dietary recall. The USDA and CDC issued two separate reports describing the per capita per day intakes from alcoholic beverages and the proportion of respondents who consumed alcoholic beverages on any given day in 2003–2006 and 2007–2010, respectively.12,13 Due to the low proportion of consumers of alcoholic beverages on any given day, per capita per day estimates may mask high intake among heavy consumers. 10,14–16 Per consumer estimates are means calculated from intakes of those who reported alcoholic beverage consumption on the day of dietary recall. Per consumer estimates provide practical information regarding intakes of individuals who actually consumed alcoholic beverages on the day of dietary assessment. Examining per consumer estimates in conjunction with the proportion of consumers, may identify subgroups at risk of excess calorie intake from alcoholic beverages on days when drinking occurs, particularly if the proportion of consumers is low and calorie intakes are high. No study to date has examined in-depth factors underlying trends in per capita per day alcoholic beverage energy intake by race/ethnicity, income and education groups subsequent to the enactment of the NMDAA and the 1990 DGAs.

In a recent systematic review, differential associations between alcoholic beverage type and diet and health outcomes were reported across studies. 7 Wine drinking has been linked with higher intakes of food and beverage groups supported by the DGA, and beer intake has been associated with obesity. 17–19 Yet, there is a gap in knowledge of the consumption of different types of alcoholic beverages among age, sex, race/ethnicity and socio-economic status (SES) groups across time. 20,21 Select national level reports provide estimates of per capita ethanol availability and sales (in gallons or liters) at the national and regional levels. These reports indicate that sources of ethanol by beverage type have remained relatively constant over the past two decades, with most ethanol coming from beer, followed in order by liquor and wine. These measures are based on reported volumes of ethanol available for sale and miss trends in calories consumed by beverage type and across socio-demographic subpopulations.22,23 Cross-sectional studies conducted in the US indicate that wine and beer preferences have been associated with female and male sex, respectively.17,24 Moreover, wine preference has been associated with higher educational attainment, while liquor preference has been associated with older age. 18,24–26 These cross-sectional studies typically used questionnaires that measure the number and frequency of drinks, but did not assess energy intake from alcoholic beverages in total or by beverage type 10,13,27–29 It remains unknown whether there have been shifts in the top contributors to alcoholic beverage calories within subpopulations over time.

The current study’s objective was to determine 20-year trends in energy intake from alcoholic beverages among US adults, overall and across multiple socio-demographic subgroups. For comparability with earlier studies, trends in per capita per day intakes were examined. To explore factors underlying these trends, the proportion of consumers on any given day and calories per consumer were determined. These data are important for characterizing intake among population subgroups actually reporting consumption on the day of recall. To inform future studies aimed at understanding alcoholic beverage consumption by beverage type, shifts in the percentage contributions of alcoholic beverages by type and across population subgroups were ascertained.

METHODS

Dietary Assessment Methods

Dietary intake data for the 1989–1991 Continuing Survey of Food Intakes by Individuals (CSFII89-91) were collected on three consecutive days: one in-person, interviewer-administered 24-hour dietary recall (24-hr recall) and one self-administered two-day diet record.30 The 1994–1996 Continuing Survey of Food Intakes by Individuals (CSFII94-96) collected two nonconsecutive days of interviewer-administered 24-hour dietary recalls using multiple-pass methodology. 31 All National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) were interviewer-administered using the USDA Automated Multiple-Pass Method and included one in-person 24-hr recall and a second recall collected 3 to 10 days later by phone. 32–35 NHANES surveys were pooled to combine 2003–2004 with 2005–2006 (NHANES03-06) and 2009–2010 with 2011–2012 (NHANES09-12). To maximize comparability across survey years, the first day of dietary intake data from each survey was used. Detailed information regarding collection of socio-demographic data is provided through the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service. In brief, age, sex, race/ethnicity, household income and education data were obtained via trained interviewer administered questionnaires for all surveys.30–34,36 The University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board has determined that this submission does not constitute human subjects research as defined under federal regulations [45 CFR 46.102 (d or f) and 21 CFR 56.102(c)(e)(l)] and does not require IRB approval.

Alcoholic Beverage Categorization

For all surveys the USDA assigned an 8 digit food code number specific to each beverage reported. Food codes reported in each survey were linked to food composition tables corresponding to the time period of data collection and based on the USDA Nutrient Database for Standard Reference. 30,35 Food codes were grouped into three mutually exclusive categories of alcoholic beverages: beer, wine, liquor/mixed drinks. For alcoholic beverages reported with the use of combination codes, components were summed and the combined beverage was categorized as a mixed drink. Alcoholic beverages used in food preparation were excluded from all analyses. 12

Analytic Sample

This analysis of cross-sectional data included adults ≥ 19 years with 1 day of 24-hr recall data deemed reliable by study developers and corresponding study-provided survey weights. Following procedures established by NHANES, a variable indicating the quality and completeness of a survey participant’s responses to the dietary recall section was utilized to indicate reliable 24-hr recall data. 37,38 Following NHANES analytic guidelines, the day 1 24-hr recall survey weight variables were utilized and standardized across survey years. Respondents with missing covariate data were excluded (<10% of the study population at each survey). The final analytic dataset is described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Distribution of socio-demographic characteristics among US adults and alcoholic beverage consumers aged ≥19 years, 1989–2012a

| CSFIIb 1989–1991 N= 10,501 |

CSFII 1994–1996 N= 9,851 |

NHANESc 2003–2006 N= 9,019 |

NHANES 2009–2012 N= 9,927 |

CSFII 1989–1991 n=1,218 |

CSFII 1994–1996 n=1,649 |

NHANES 2003–2006 n=1,990 |

NHANES 2009–2012 n=2,224 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Overall | Consumers | |||||||

| Age group, % | ||||||||

| 19–39 years | 47.2 ± 1.3 | 45.2 ± 0.9 | 39.7 ± 1.1*** | 38.1 ± 1.5*** | 48.4 ± 2.1 | 49.2 ± 1.4* | 39.8 ± 1.7** | 37.0 ± 1.8 |

| 40–59 years | 30.0 ± 0.9 | 32.9 ± 0.7 | 36.9 ± 0.8*** | 37.4 ± 0.8*** | 35.7 ± 2.1 | 34.8 ± 1.1 | 42.0 ± 1.2 | 41.5 ± 1.6 |

| 60+ years | 22.8 ± 0.9 | 21.9 ± 0.7 | 23.4 ± 1.1 | 24.5 ± 0.9 | 16.0 ± 1.8 | 16.0 ± 1.1 | 18.2 ± 1.7 | 21.5 ± 1.5 |

| Mean ± SE (years) | 45 ± 1 | 45 ± 0 | 46 ± 1* | 47 ± 1* | 43 ± 1 | 42 ± 1 | 45 ± 1 | 46 ± 1** |

| Sex, % | ||||||||

| Men | 46.9 ± 0.6 | 47.8 ± 0.5 | 48.0 ± 0.5 | 48.7 ± 0.6 | 65.1 ± 1.7 | 64.5 ± 1.3 | 63.6 ± 1.1 | 60.5 ± 1.2 |

| Women | 53.1 ± 0.6 | 52.2 ± 0.5 | 52.0 ± 0.5 | 51.3 ± 0.6 | 34.9 ± 1.7 | 35.5 ± 1.3 | 36.4 ± 1.1 | 39.5 ± 1.2 |

| Race/ethnicity d, % | ||||||||

| NHW | 79.7 ± 1.6 | 75.8 ± 1.9 | 72.7 ± 2.3 | 68.6 ± 2.6*** | 84.9 ± 1.7 | 85.1 ± 1.8 | 77.9 ± 1.9 | 76.8 ± 1.9* |

| NHB | 10.5 ± 1.1 | 11.1 ± 1.1 | 11.5 ± 1.4 | 11.2 ± 1.3 | 8.2 ± 1.6 | 5.5 ± 0.7 | 9.4 ± 1.2 | 9.4 ± 1.1 |

| Mex-Am | 7.3 ± 1.1 | 4.0 ± 0.6 | 7.8 ± 1.1 | 7.9 ± 1.4 | 5.6 ± 1.1 | 2.6 ± 0.5 | 5.6 ± 1.1 | 5.3 ± 1 |

| Other | 2.5 ± 0.4 | 9.0 ± 1.3*** | 8.0 ± 0.7*** | 12.3 ± 1.0*** | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 6.7 ± 1.3* | 7.0 ± 0.9*** | 8.6 ± 0.8*** |

| Household income e, % | ||||||||

| 0–130% | 14.7 ± 0.7 | 16.1 ± 0.9 | 19.9 ± 1.3*** | 24.6 ± 1.3*** | 6.6 ± 0.7 | 7.8 ± 1.0 | 14.3 ± 1.2* | 17.8 ± 1.4* |

| 131–299% | 29.9 ± 1.4 | 31.0 ± 0.8 | 29.0 ± 0.9 | 27.3 ± 1.0 | 18.9 ± 1.9 | 24.2 ± 1.4 | 23.8 ± 1.6 | 22.5 ± 1.2 |

| ≥300% | 55.4 ± 1.6 | 52.9 ± 1.3 | 51.1 ± 1.6 | 48.1 ± 1.7* | 74.5 ± 2.2 | 68.1 ± 1.7 | 61.9 ± 2.1* | 59.7 ± 2.3* |

| Mean ± SE (FPL %) | 387 ± 11 | 237 ± 2.0* | 302 ± 6.0* | 291 ± 6.0* | 501 ± 19 | 263 ± 3*** | 338 ± 6.0*** | 334 ± 8.0*** |

| Education, % | ||||||||

| < HS | 19.3 ± 0.8 | 16.0 ± 0.9 | 17.5 ± 1.0 | 16.7 ± 1.0 | 13.0 ± 1.3 | 7.3 ± 0.8** | 12.8 ± 1.2 | 11.9 ± 1.3 |

| HSf | 35.4 ± 1.0 | 35.0 ± 1.1 | 25.8 ± 0.9*** | 21.2 ± 1.1*** | 31.2 ± 2.2 | 28.1 ± 1.5 | 23.0 ± 1.1* | 19.1 ± 1.4*** |

| Some college | 22.4 ± 1.0 | 23.4 ± 0.5 | 31.9 ± 0.8*** | 32.6 ± 1.1*** | 23.9 ± 1.7 | 26.8 ± 1.1 | 34.0 ± 1.5*** | 29.5 ± 1.4 |

| College degree | 22.9 ± 1.2 | 25.7 ± 1.4 | 24.8 ± 1.5 | 29.5 ± 1.5* | 31.9 ± 2.3 | 37.8 ± 2.2 | 30.3 ± 2.3 | 39.5 ± 2.3 |

Data for United States (US) all adults ≥19 years with reliable dietary intake data (n=39,298) and a subset of consumers who reported consuming > 0 kcal/d from an alcoholic beverage during the 24 hour period prior to the dietary recall interview (n=7,081). All proportions take into account survey design and sample weights. Values are % or means ± SE. Differences were considered statistically significant at P<0.05, after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

Different than 1989–91 (p<0.001)

Different than 1989–91 (p<0.01)

Different than 1989–91 (p<0.05)

Continuing Survey of Good Intakes by Individuals (CSFII)

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES)

Non-Hispanic white (NHW); Non-Hispanic black (NHB); Mexican-American (Mex-Am); Other race/ethnicity includes respondents who reported Asian, Pacific Islander, American Indian, other race (including multi-racial) and Non-Hispanic or other Hispanic (excluding Mex-Am) ethnic origin

Household income expressed as percentage of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL %)

Graduated from high school (HS) or obtained general equivalency diploma (GED)

Statistical Analyses

Data analyses were performed using survey commands within Stata (version 13, 2013, StataCorp, College Station, TX). Survey weights provided by the USDA were used to account for differential probabilities of selection, non-response and complex survey design. To examine trends in per capita per day intake from alcoholic beverages, the survey weighted daily mean intake of total alcoholic beverage energy was calculated overall (for all adults) and by socio-demographic subpopulations. To examine shifts in the per capita per day intakes by beverage type, the survey weighted mean intake of beverage-specific calories and the percentage contribution of each beverage type (i.e., beer, wine, liquor/mixed drinks) to total alcoholic beverage consumption were calculated. Calories per capita per day overall and by sex subgroups are presented. Due to the presence of strata containing only a single primary sampling unit within the CSFII89-91, the survey weighted calculation of per capita per day percent contributions by beverage type were analyzed with and without strata specification. 39 Means were standardized to the age, sex and race/ethnicity distribution of the NHANES09-12 pooled sample. For per consumer analyses, alcoholic beverage consumers were identified as any adult ≥19 years with calorie intake from alcoholic beverages greater than 0 kcal/day (n=7081) on day 1 of 24-hr recall. The consumer subsample is described in Table 1. The weighted unadjusted proportion of alcoholic beverage consumption was calculated overall and by socio-demographic subgroups.

To determine whether the proportion of alcoholic beverage consumers differed across time or by socio-demographic characteristics, multivariable logistic regression models were used to regress the binary outcome of alcoholic beverage consumption on survey year (indicator variables). To determine trends in per consumer mean daily intakes from alcoholic beverages across subgroups, linear regression models restricted to alcoholic beverage consumers were used. Regression models were adjusted for age group (19–39, 40–59, ≥ 60 years), sex, race/ethnicity group (non-Hispanic white [NHW], non-Hispanic black [NHB], Mexican American [Mex-Am], and other), education (less than high school [< HS], high school graduate [HS], some college, or college degree), family income based on the federal poverty level (FPL) thresholds for supplemental assistance programs available to adults (0–130% FPL, 131–299% FPL, ≥ 300% FPL), and recall day of the week (weekend [Friday through Sunday] or weekday [Monday through Thursday]).27 To determine if trends differed across subgroups, interactions of time and each of the following covariates were tested: age group, sex, race/ethnicity, income and education. Wald’s chunk test was used to determine the joint significance of interaction product terms with significance set at p<0.10. Stata’s margins command was used to determine the adjusted mean probability of consumption (subgroup-specific proportion) and mean per consumer intakes overall and among subgroups. To test for linear trends, several adjusted multivariable logistic and linear models were used in which alcoholic beverage calorie consumption was the dependent variable and survey year was treated as a continuous variable interacted with each of the following covariates: age group, sex, race/ethnicity, income and education. Year was defined as the number of years since the CSFII89-91 survey. Stata’s lincom command was used to calculate the p-value associated with the sum of the β co-efficient of the trend variable plus the β co-efficient of the interaction term.

To provide context for alcoholic beverage energy intake in relation to total energy intake, survey weighted multivariable regression models were used to estimate the average percentage contribution of alcoholic beverage energy to total energy intake (% kcal) per capita per day and per consumer.

To examine the shifts in beverage type among consumers, the survey weighted daily mean intake of each beverage type and the percentage contribution of each beverage type to total alcoholic beverage consumption among consumers were determined overall and by population subgroups. For comparability, means were standardized to the age, sex and race/ethnicity distribution of alcoholic beverage consumers from NHANES09-12.

Alcoholic beverages are episodically consumed and consumption by infrequent drinkers may not be captured by a single 24-hr recall. NHANES collects data regarding alcohol use over the past 12 months for respondents ≥ 20 years of age as part of the Mobile Examination Component using an Alcohol Use Questionnaire (ALQ). 40–43 To examine the frequency of drinking in the past 12 months, supplemental analyses were performed. A subsample of adults aged ≥ 21 years from NHANES03-06 and NHANES09-12 with complete ALQ data were identified (N=11,134) from the current study sample. Survey weighted multivariable logistic regression models were used to estimate the prevalence of drinking in the past 12 months using the ALQ and, for comparison, the proportion of drinkers on any given day using the 24-hr recall. Stata’s margins command and dydx option were used to estimate the mean difference in predicted probabilities between NHANES03-06 and NHANES09-12.

Pair-wise comparisons were conducted using t-tests across survey years and within each survey year across socio-demographic subgroups. Differences were considered statistically significant at P<0.05, after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

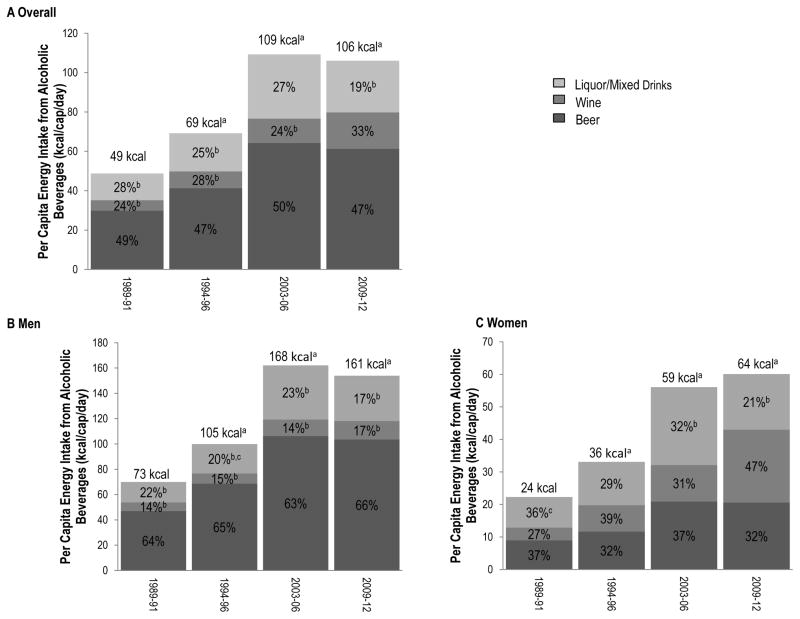

Socio-demographic characteristics of the study population and consumer subsample are provided in Table 1. Overall, per capita per day intake from alcoholic beverages increased from 49 kcal/cap/d in 1989–1991 to 109 kcal/cap/d in 2003–2006 and remained stable from 2003–2006 through 2009–2012 for both men and women (Figure 1) and for all population subgroups (Table 2). Per capita per day intakes of NHW exceeded that of Mex-Am in 2003–2006 and 2009–2012 (p < 0.05). Increases in per capita per day intakes were observed across all three beverage types, overall and by sex subgroups (Supplemental Table 1).

Figure 1. Per capita energy intake from alcoholic beverages and percent contribution by beverage type to total alcoholic beverage energy intake overall and by sex, 1989–2012.

Panel labels:

- Overall

- Men

- Women

Data for adults (≥19 y) who reported dietary intake on day 1 of diet assessment from the Continuing Survey of Food Intakes by Individuals (CSFII) 1989–91, CSFII 1994–1996, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2003–2006, and NHANES 2009–2012 (N= 39,298). Percentages indicate the contribution of beer, wine or liquor/mixed drinks kcal/d to energy intake from alcoholic beverages at each survey year and are calculated at the person level; percentages are the mean percent contribution and may differ from percentages calculated by the population ratio method. Differences were considered statistically significant at P<0.05, after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. a Significantly different than 1989–1991 (P<0.001); b Within year different than beer (p<0.05); c Within year different than wine (p<0.05).

Table 2.

Per capita energy intake (kcal/cap/day) from alcoholic beverages among US adults aged ≥ 19 years, 1989–2012a

| CSFIIb 1989–1991 N= 10501 |

CSFII 1994–1996 N= 9851 |

NHANESc 2003–2006 N= 9019 |

NHANES 2009–2012 N= 9927 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overalld | 49 ± 3 | 69 ± 4*** | 109 ± 5*** | 106 ± 6*** |

| Age groupe | ||||

| 19–39 years | 55 ± 5 | 90 ± 5*** | 121 ± 8*** | 119 ± 9*** |

| 40–59 years | 50 ± 5 | 65 ± 6 | 130 ± 9*** | 119 ± 11*** |

| 60+ years | 22 ± 3 | 33 ± 2* | 58 ± 4*** | 64 ± 4*** |

| Sexf | ||||

| Men | 73 ± 5 | 105 ± 7*** | 168 ± 8*** | 161 ± 13*** |

| Women | 24 ± 2 | 36 ± 3*** | 59 ± 4*** | 64 ± 4*** |

| Race/ethnicityd | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 51 ± 3 | 78 ± 5*** | 117 ± 5*** | 119 ± 8*** |

| Non-Hispanic black | 40 ± 9 | 47 ± 7 | 94 ± 8*** | 97 ± 8*** |

| Mexican-American | 39 ± 8 | 42 ± 6 | 76 ± 8*** | 68 ± 4*** |

| Household incomed,g | ||||

| 0–130% | 32 ± 3 | 61 ± 11* | 96 ± 6*** | 96 ± 9*** |

| 131–299% | 40 ± 5 | 60 ± 5** | 100 ± 10*** | 90 ± 8*** |

| ≥300% | 57 ± 4 | 77 ± 5** | 119 ± 6*** | 118 ± 8*** |

| Educationd | ||||

| < HS | 52 ± 8 | 51 ± 6 | 115 ± 12*** | 91 ± 9*** |

| HSh | 50 ± 5 | 67 ± 7 | 106 ± 11*** | 117 ± 13*** |

| Some college | 50 ± 5 | 76 ± 7*** | 118 ± 10*** | 102 ± 8*** |

| College degree | 49 ± 6 | 77 ± 5*** | 100 ± 8*** | 111 ± 8*** |

Data for United States (US) adults ≥19 years who reported dietary intake on day 1 of diet assessment (N=39,298). Values are means ± SE. All estimates take into account survey design and sample weights. Differences were considered statistically significant at P<0.05, after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

Different than 1989–91 (p<0.001)

Different than 1989–91 (p≤ 0.01)

Different than 1989–91 (p<0.05)

Continuing Survey of Food Intakes by Individuals (CSFII)

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES)

Estimates standardized to the age and sex distribution of the NHANES 2009–2012 pooled sample.

Estimates standardized to the sex and race/ethnic distribution of the NHANES 2009–2012 pooled sample.

Estimates standardized to the age and race/ethnic distribution of the NHANES 2009–2012 pooled sample.

Household income expressed as percentage of the Federal Poverty Level

Graduated from high school (HS) or obtained general equivalency diploma (GED)

Shifts in subpopulations consuming any alcohol

The overall unadjusted proportion of consumers on any given day increased significantly from 15.4% in 1989–1991 to 25.0% in 2009–2012 (Table 3). Similar increases were observed for each population subgroup except Mex-Am. Due to small sample sizes, results for those categorized as “other race/ethnicity” should be interpreted with caution and are not presented for subsequent analyses.

Table 3.

Unadjusted proportion of alcoholic beverage consumers among US adults aged ≥19 years, 1989–2012a

| CSFII b 1989–1991 N= 10501 |

CSFII 1994–1996 N= 9851 |

NHANESc 2003–2006 N= 9019 |

NHANES 2009–2012 N= 9927 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall, % | 15.4 ± 0.9 | 17.5 ± 0.7 | 24.6 ± 0.9d,e | 25.0 ± 0.9d |

| Age group, % | ||||

| 19–39 years | 15.8 ± 1.1 | 19.0 ± 0.9 | 24.7 ± 1.3d,e | 24.3 ± 1.0d |

| 40–59 years | 18.4 ± 1.3 | 18.5 ± 0.9 | 28.0 ± 1.3d,e | 27.8 ± 1.7d |

| 60+ years | 10.8 ± 1.4 | 12.8 ± 1.0 | 19.2 ± 1.4d,e | 21.9 ± 1.4d |

| Sex, % | ||||

| Men | 21.5 ± 1.1 | 23.6 ± 0.9 | 32.6 ± 1.1d,e | 31.1 ± 1.1d |

| Women | 10.0 ± 1.0 | 12.0 ± 1.0 | 17.0 ± 1.0d,e | 19.0 ± 1.0d |

| Race/ethnicity, % | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 16.5 ± 1.1 | 19.6 ± 0.8 | 26.4 ± 1.2d,e | 28.0 ± 1.2d |

| Non-Hispanic black | 11.9 ± 2.0 | 8.7 ± 1.0 | 20.1 ± 1.6d,e | 20.8 ± 1.3d |

| Mexican-American | 11.9 ± 1.5 | 11.4 ± 1.7 | 17.7 ± 1.9 | 16.8 ± 1.2 |

| Other f | 8.4 ± 2.4 | 13.0 ± 1.2 | 21.7 ± 2.0d,e | 17.4 ± 1.3d |

| Household income g, % | ||||

| 0–130% | 6.9 ± 0.5 | 8.5 ± 1.1 | 17.7 ± 1.2d,e | 18.1 ± 1.0d |

| 131–299% | 9.8 ± 1.0 | 13.6 ± 0.8d | 20.2 ± 1.4d,e | 20.6 ± 1.3d |

| ≥300% | 20.7 ± 1.4 | 22.5 ± 0.9 | 29.8 ± 1.2d,e | 31.0 ± 1.3d |

| Education, % | ||||

| < HS | 10.4 ± 1.1 | 8.0 ± 0.6 | 18.0 ± 1.3d,e | 17.8 ± 1.3 d |

| HS h | 13.6 ± 1.1 | 14.0 ± 0.7 | 21.9 ± 1.8d,e | 22.5 ± 1.4 d |

| Some college | 16.5 ± 1.5 | 20.1 ± 1.3 | 26.3 ± 1.5d,e | 22.6 ± 1.1d |

| College degree | 21.5 ± 1.9 | 25.7 ± 1.0 | 30.0 ± 1.3d | 33.5 ± 1.6d |

| Recall Day of Week, % | ||||

| Weekday (Mon–Thur) | 18.1 ± 1.2 | 21.2 ± 0.9 | 28.6 ± 1.5d,e | 27.2 ± 1.1d |

| Weekend (Fri–Sun) | 13.4 ± 1.0 | 14.7 ± 0.7 | 21.6 ± 1.0d,e | 23.4 ± 0.9d |

Data for United States (US) adults ≥19 years with reliable dietary intake data (n=39,298). All proportions take into account survey design and sample weights. Values are % ± SE. Differences were considered statistically significant at P<0.05, after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

Continuing Survey of Food Intakes by Individuals (CSFII)

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES)

Different than 1989–91 (p≤0.01)

Different than 1994–96 (p<0.05)

Includes respondents who reported Asian, Pacific Islander, American Indian, other race (including multi-racial) and Non-Hispanic or other Hispanic (excluding Mex-American) ethnic origin

Household income expressed as percentage of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL%)

Graduated from high school (HS) or obtained general equivalency diploma (GED)

Overall, the adjusted proportion of adults who consumed alcoholic beverages on any given day increased from 12.8% in 1989–1991 to 23.8% in 2009–2012 (Table 4). With the exception of Mex-Am, the proportion of alcoholic beverage consumers was higher in 2009–2012 compared to 1989–91 within each socio-demographic subpopulation.

Table 4.

Adjusted proportion of alcoholic beverage consumers on any given day among US adults aged ≥19 years, 1989–2012a

| CSFII 1989–1991 N= 10501 |

CSFII 1994–1996 N= 9851 |

NHANES 2003–2006 N= 9019 |

NHANES 2009–2012 N= 9927 |

Ptrend d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall, % | 12.8 ± 1.0 | 15.1 ± 0.5 | 23.2 ± 0.9e,f | 23.8 ± 0.9e,f | <0.0001 ↑ |

| Age group, % | |||||

| 19–39 years | 14.2 ± 1.0 | 15.9 ± 0.6 | 24.3 ± 1.0e,f | 24.5 ± 0.8e | <0.0001 ↑ |

| 40–59 years | 14.3 ± 1.0 | 16.1 ± 0.7 | 24.5 ± 1.1e,f | 24.8 ± 1.1e | <0.0001 ↑ |

| 60+ years | 11.1 ± 1.0g | 12.5 ± 0.6g | 19.5 ± 1.0e,f,g | 19.7 ± 0.9e,g | <0.0001 ↑ |

| Sex, % | |||||

| Men | 18.9 ± 1.0h | 21.0 ± 0.7 h | 31.0 ± 1.1e,,f,h | 31.1 ± 1.0e,h | <0.0001 ↑ |

| Women | 9.8 ± 1.0 | 11.0 ± 0.4 | 17.3 ± 0.8e,f | 17.4 ± 0.7e | <0.0001 ↑ |

| Race/ethnicity, % | |||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 13.6 ± 0.9 | 17.0 ± 0.7 | 24.5 ± 1.1e,f | 25.7 ± 1.1e | <0.0001 ↑ |

| Non-Hispanic black | 13.2 ± 2.4 | 9.0 ± 1.1i | 20.5 ± 1.7f | 22.2 ± 1.4e | <0.0001 ↑ |

| Mexican-American | 12.8 ± 1.7 | 12.4 ± 1.5 | 18.7 ± 1.9 | 17.8 ± 1.2i | <0.0001 ↑ |

| Household incomej, % | |||||

| 0–130% | 7.3 ± 0.7 | 10.7 ± 1.3 | 19.0 ± 1.3e,f | 20.1 ± 1.3e | <0.0001 ↑ |

| 131–299% | 9.4 ± 1.0 | 13.4 ± 0.7 | 20.5 ± 1.4e,f | 20.8 ± 1.4e | <0.0001 ↑ |

| ≥300% | 18.2 ± 1.3k | 18.1 ± 0.8k | 26.6 ± 1.2e,f,k | 27.2 ± 1.4e,k | <0.0001 ↑ |

| Education, % | |||||

| < HS | 11.7 ± 1.2 | 9.5 ± 0.7l | 20.5 ± 1.7e,f | 20.6 ± 2.0e | <0.0001 ↑ |

| HSm | 11.6 ± 1.0 | 12.7 ± 0.7l | 21.2 ± 1.8e,f | 22.1 ± 1.5e | <0.0001 ↑ |

| Some college | 13.5 ± 1.2 | 17.7 ± 1.1 | 24.7 ± 1.4e,f | 22.2 ± 1.1e | <0.0001 ↑ |

| College degree | 14.3 ± 1.5 | 20.3 ± 1.0e | 26.0 ± 1.2e,f | 30.5 ± 1.6e,n | <0.0001 ↑ |

Data for United States (US) adults ≥19 years with reliable dietary intake data (n=39,298). Values are % ± SE. Probability estimates obtained from multivariable logistic regression model adjusted for sex, age group, race/ethnicity, household income, education, recall day of the week, time x race/ethnicity, time x education, and time x income interaction terms using margins command in Stata version 13. All estimates take into account survey design and sample weights. Differences were considered statistically significant at P<0.05, after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

Continuing Survey of Food Intakes by Individuals (CSFII)

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES)

Refers to the p value associated with the sum of the β co-efficient of the survey year treated as a continuous variable and interacted with the socio-demographic covariate of interest.

Different than 1989–91 (p<0.05)

Different than 1994–96 (p<0.01)

Different than 19–39 yrs. and 40–59 yrs. (p<0.01)

Different than women (p<0.01)

Different than Non-Hispanic white (p<0.01)

Household income expressed as percentage of the Federal Poverty Level

Different than 0–130% and 131–299% (p<0.05)

Different than Some college and College degree (p<0.05)

Graduated from high school (HS) or obtained general equivalency diploma (GED)

Different than HS, <HS and Some college (p≤0.01)

Based on Wald’s chunk tests, the final multivariable logistic regression model included an interaction term for race/ethnicity (p for interaction = 0.02), income (p for interaction = 0.02), and education (p for interaction < 0.01). Despite similarities in the proportion of consumers on any given day among race/ethnicity groups in 1989–1991, disparities existed in 2009–2012, with the proportion of NHW consumers on any given day significantly higher than that of Mex-Am. Furthermore, the proportion of consumers increased between 1989–1991 and 2009–2012 for NHW and NHB, whereas the trend for Mex-Am was relatively stable over time. The low and middle income groups had a lower probability of consumption at every survey year as compared to those in the highest income group. In 1989–1991 the proportion of consumers with income ≥ 300% FPL was more than double that of those in the lowest income group; however, the gap between income groups narrowed by 2009–2012. Disparities between education groups did not exist in 1989–1991; however, in 2009–2012 the proportion of consumers with a college degree (30.5%) was higher than that of adults with <HS education (20.6%).

Per consumer intakes from alcoholic beverages on any given day

Table 5 illustrates the mean daily alcoholic beverage calories consumed among those who reported alcoholic beverage consumption on day 1 of 24-hr recall. Overall, per consumer calories from alcoholic beverages increased significantly between 1989–1991 and 1994–1996. An increasing linear trend in calories per consumer calories was found (ptrend = 0.0002). With the exception of income subgroups, this pattern was observed for each socio-demographic subpopulation. The final multivariable regression model included an interaction term for income (p for interaction = 0.01). Per consumer intakes from alcoholic beverages were significantly higher in 2009–2012 than in 1989–1991 for adults in the lowest and highest income categories; however, significant increases were not seen for those in the middle income subgroup. An increasing linear trend was observed for the highest income subgroup only (p < 0.0001). At each time point the per consumer intake from alcoholic beverages was significantly higher for adults 19–39 and 40–59 years old compared to adults ≥ 60 years, for men compared to women, for NHW compared to Mex-Am, and for adults with <HS education compared to those with some college or college degree. Calories per consumer tended to be higher among low-income compared to high-income adults, but these differences only reached statistical significance in 1994–1996.

Table 5.

Adjusted per consumer mean daily energy intake (kcal/d) from alcoholic beverages among US adults aged ≥ 19 years, 1989–2012a

| CSFIIb 1989–1991 n= 1218 |

CSFII 1994–1996 n= 1649 |

NHANESc 2003–2006 n= 1990 |

NHANES 2009–2012 n= 2224 |

Ptrendd | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 302 ± 15 | 409 ± 14e | 440 ± 11e | 441 ± 19e | 0.0002 ↑ |

| Age group | |||||

| 19–39 years | 363 ± 17 | 453 ± 17e | 497 ± 15e | 483 ± 20e | 0.006 ↑ |

| 40–59 years | 312 ± 17 | 402 ± 18e | 446 ± 15e | 432 ± 22e | <0.0001 ↑ |

| 60+ years | 188 ± 16f | 278 ± 15e,f | 322 ± 13e,f | 308 ± 14e,f | <0.0001 ↑ |

| Sex | |||||

| Men | 371 ± 16g | 462 ± 17e,g | 501 ± 13e,g | 485 ± 20e,g | <0.0001 ↑ |

| Women | 215 ± 16 | 307 ± 15e | 345 ± 13e | 330 ± 15e | <0.0001 ↑ |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 325 ± 15h | 415 ± 15e,h | 456 ± 11e,h | 437 ± 19e,h | <0.0001 ↑ |

| Non-Hispanic black | 296 ± 19 | 386 ± 20e | 427 ± 18e | 408 ± 20e | 0.587 |

| Mexican-American | 236 ± 26 | 326 ± 27e | 367 ± 23e | 348 ± 28e | 0.255 |

| Household incomei | |||||

| 0–130% | 324 ± 26 | 618 ± 54e,j | 466 ± 29e | 517 ± 46e | 0.582 |

| 131–299% | 365 ± 48 | 404 ± 29 | 444 ± 24 | 419 ± 30 | 0.289 |

| ≥300% | 276 ± 14 | 371 ± 17e | 434 ± 15e | 434 ± 25e | <0.0001 ↑ |

| Education | |||||

| < HS | 406 ± 25k | 509 ± 25e,k | 537 ± 25e,k | 528 ± 27e,k | 0.100 |

| HSl | 372 ± 22 | 474 ± 22e | 502 ± 18e | 494 ± 29e | 0.027 |

| Some college | 317 ± 18 | 419 ± 21e | 448 ± 17e | 439 ± 20e | <0.0001 ↑ |

| College degree | 226 ± 18m | 329 ± 15e,m | 357 ± 15e,m | 348 ± 17e,m | <0.0001 ↑ |

Data for United States (US) adults ≥19 years who reported alcoholic beverage consumption on day 1 of dietary assessment (n=7,081). Values are means ± SE. Mean estimates obtained from multivariable linear regression model adjusted for sex, age group, race/ethnicity, household income, education, recall day of the week and time x income interaction terms using margins command in Stata version 13. All estimates take into account survey design and sample weights. Differences were considered statistically significant at P<0.05, after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

Continuing Survey of Food Intakes by Individuals (CSFII)

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES)

Refers to the p value associated with the sum of the β co-efficient of the survey year treated as a continuous variable and interacted with the socio-demographic covariate of interest.

Different than 1989–91 (p<0.05)

Different than 19–39 yrs and 40–59 yrs (p<0.01)

Different than women (p<0.01)

Different than Mex-Am (p<0.05)

Household income expressed as percentage of the Federal Poverty Level

Different than ≥ 300% FPL (p<0.01)

Different than some college and college degree (p<0.05)

Graduated from high school (HS) or obtained general equivalency diploma (GED)

Different than <HS, HS and some college (p<0.01)

Percentage contribution from alcoholic beverages to total energy intake

Overall, the per capita per day percentage contribution of alcoholic beverages to total energy intake increased from 2.1 % (1989–1991) to 4.3% (2009–2012) (Supplemental Table 2). Significant increases were observed for all socio-demographic subgroups. Overall, the per consumer percentage contribution from alcoholic beverages to total energy intake increased from 14.0 % (1989–1991) to 17.2% (2009–2012) (Supplemental Table 3). With the exception of the low and middle income subgroups, significant increases were observed for all socio-demographic groups.

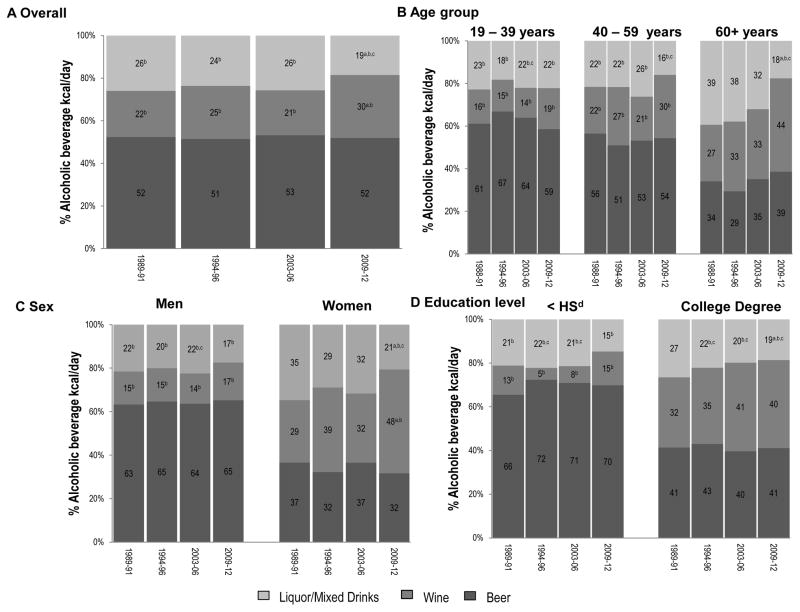

Percentage contribution from alcoholic beverages by type

Sample sizes were inadequate to examine trends in percent contribution of each alcoholic beverage type for race/ethnicity or income subgroups. Overall, beer intake was the top contributor to alcoholic beverages across all survey years (Figure 2). A shift occurred between 2003–2006 and 2009–2012, when wine intake increased from 21.1% to 29.6% of alcoholic beverage consumption (p < 0.01) and liquor/mixed drink intake decreased from 25.7% to 18.5% (p = 0.01) of alcoholic beverage calories consumed.

Figure 2. Per consumer percentage contribution of alcoholic beverages by type to total alcoholic beverage energy intake A) overall, and by B) age group, C) sex, and D) education level, 1989–2012.

Data for adults (≥19 y) who reported alcoholic beverage consumption on day 1 of diet assessment from the Continuing Survey of Food Intakes by Individuals (CSFII) 1989–91, CSFII 1994–1996, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2003–2006, and NHANES 2009–2012. Percentages indicate the contribution of beer, wine or liquor/mixed drinks kcal/d to energy intake from alcoholic beverages at each survey year. Differences were considered statistically significant at P<0.05, after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. a Significantly different than 1989–1991 (p<0.001); b Within year different than beer (p<0.05); c Within year different than wine (p<0.05). d HS, High school

In 1994–1996, liquor/mixed drinks made a greater contribution to alcoholic beverage intake among those in the oldest age group (37.8%) compared to adults in youngest age group (18.2%) (p<0.01). From 1994–1996 onward, the contribution from wine was greater among those ≥ 60 years of age as compared to those 19–39 years (p<0.01 for pairwise comparisons at each survey year). Per consumer intake from wine increased from 39 kcal/d in 1989–1991 to 97 kcal/d in 2009–2012 among adults ≥ 60 years (Supplemental Table 4). By 2009–2012, wine (43.8%) and beer (38.6%) were both large contributors to alcoholic beverage intakes among adults ≥ 60 years, with liquor/mixed drinks making a lesser contribution (17.6%) (Figure 2).

All alcoholic beverages contributed similarly to intake among women until 2009–2012. Between 2003–2006 and 2009–2012, there was a shift away from liquor/mixed drinks (31.7% to 20.6%, p=0.06) towards wine (31.8% to 47.7%, p<0.0001) for women. The percent contribution from wine intake among women nearly doubled between 1989–1991 and 2009–2012 (Figure 2). Calories per consumer from wine among women increased from 40 kcal/d in 1989–1991 to 113 kcal/d in 2009–2012 (Supplemental Table 4).

For the lowest education group, in both 1994–1996 and 2003–2006, liquor/mixed drinks were the second contributor while wine intakes fell below 10%. Conversely, for those with a college degree, the contributions from wine and beer were similar and stable, while liquor/mixed drinks contributed least to alcoholic beverage intake from 1994–1996 onward (Figure 2). The contribution of beer to alcoholic beverage intake among adults with <HS education (~70% kcal) exceeded those with a college degree (~40% kcal) at each time point (p<0.01 for pairwise comparisons at each survey year). Wine contributions among adults with a college degree exceeded those of the lowest education group for all years (p≤0.01 for pairwise comparisons at each survey year) (Figure 2).

Categorizing drinkers based on the ALQ40–43

Overall, based on the frequency questionnaire, the 12-month prevalence of drinking increased from 73.0% (2003–2006) to 79.9% (2009–2012) (Supplemental Table 5). Significant increases were observed for age, sex, and NHB subgroups. Increases for women (+8.5 %) and among those ≥ 60 yrs (+9.0%) were greater as compared to men and those 19 – 59 years, respectively. Among NHB, the prevalence of consuming alcoholic beverages was 12.5% higher in 2009–2012 compared to 2003–2006. This change was significantly greater than the change among Mex-Am (−1.7%). In comparison, changes between 2003–2006 and 2009–2012 in the proportion of consumers on any given day were generally smaller than 12 month estimates of changes across time; additionally, changes across time in the proportion consuming on any given day were not significant, overall or by population subgroups.

DISCUSSION

In this nationally representative sample, overall per capita per day intake from alcoholic beverages increased from 1989–1991 to 2009–2012. Underlying these trends were increases in the proportion consuming alcoholic beverages on any given day and increases in per consumer intakes. Mex-Am experienced an increasing trend in per consumer alcoholic beverage energy intake, while the proportion who reported consumption remained relatively stable. Less educated and lower income adults tended to be less likely to consume alcoholic beverages, yet among consumers had intakes that met or exceeded that of their higher SES counterparts. There has been a recent shift making wine the top contributor of alcoholic beverage intake for women and those ≥60 years. Over this same time period, the overall per capita per day and per consumer percentage contribution of alcoholic beverages to total energy intake has increased.

Recent reports describe the proportion of drinkers on any given day based on alcohol consumption from 24-hr recall data. 12,13 In a 2012 data brief using NHANES 2007–2010 combined, the NCHS reported that on any given day, 32.7% of men and 18.0 % of women consumed calories from alcoholic beverages. 13 The current findings expand on these estimates and indicate that the adjusted proportion of men (31.1%) and women (17.4%) drinking on any given day has remained relatively stable since 2003–2006. Moreover, these results indicate that the adjusted proportion of respondents reporting alcoholic beverage consumption on day 1 of the 24-hr recall has increased from 12.8% in 1989–1991 to ~ 23.0% in 2003–2006 and 2009–2012.

The current study findings add to previous research using CSFII and NHANES data to investigate trends in per capita per day and per consumer alcoholic beverage intakes. In a 2010 study, Popkin reported that per capita per day intakes rose from 46 (1989–1991) to 65 (1994–1998) to 115 kcal/cap/d (2005–2006). 11 The current study reported almost identical estimates in per capita per day intakes. Studies of calories per capita per day from alcoholic beverages by race/ethnicity using NHANES data are limited. One study by the NCHS, reported calories per capita per day for NHW (105 kcal/cap/d) and NHB (100 kcal/cap/d) for NHANES 2007–2010 combined. 13 In comparison, the current study reported estimates of 119 and 97 kcal/cap/d for NHW and NHB, respectively, in NHANES 2009–2012. The current study contributes to previous reports by illustrating a leveling off of per capita per day intakes, overall and by race/ethnicity, from 2003–2006 up to 2009–2012. Duffey and Popkin reported a +109 kcal/d difference in average per consumer intakes reported on the National Food Consumption Survey of 1965 (272 kcal/d) compared to intakes from NHANES 1999–2002 combined (381 kcal/d) among US adults. 10 In comparison the current study indicates that per consumer intakes may have increased since NHANES 1999–2002 to 440 (kcal/d) in NHANES 2003–2006.

Examining per consumer subgroup intakes allows for comparing trends in the proportion of consumers with the calories consumed among consumers on any given day. The proportion of drinkers increased for NHW and NHB between 1989–1991 and 2003–2006 but remained stable for Mex-Am. During the same time period, per consumer intakes increased for all three race/ethnicity subgroups. Differential trends in proportion consuming and per consumer intakes may be indicative of cultural differences in daily drinking behaviors. 44,45 Results from previous studies indicate that Mex-Am race/ethnicity is associated with heavy episodic drinking (≥ 3 drinks per occasion), particularly among males. 45 Heavy episodic drinking among Latinos in the US appears to have remained stable across the 1980s and 1990s and from 2004–2008 with an increase in 2009. 46,47 Although, not significant the results of the current study suggest a peak in the proportion of consumers on any given day from 2003 through 2012. The stable prevalence of drinking coupled with an increase in calories per consumer among Mex-Am observed in the current study may be indicative of a trend towards heavy drinking behavior on days when alcoholic beverages are consumed. Moreover, in agreement with our findings, NHB race/ethnicity has been associated with an increasing trend in volume and frequency over time resulting in a drinking pattern more similar to NHW. 44,45 These findings add to the current literature by introducing per consumer alcoholic beverage calories derived from 24-hr recall data as a potential metric for monitoring alcoholic beverage use in the US. Future efforts should focus on understanding per consumer intakes on any given day, by age and sex within race/ethnicity subgroups.

Comparisons of the proportion consuming and the calories per consumer by income and education indicate that individuals in low SES subgroups may be at risk of excess alcoholic beverage consumption when drinking occurs. Respondents with income ≤130% FPL had the lowest proportion of consumers at every survey year. Yet, low income adults had similar per consumer intakes from alcoholic beverages compared to high-income adults. To this point, using the 1992 National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Study data Dawson et al reported that the probability of being a current drinker increased with income. However, the per consumer probability of drinking heavily was inversely related to income. 20 Similarly those with < HS education had higher daily per consumer intakes as compared to adults with a college degree for all survey years. In 2009–2012, per consumer intakes in the lowest income and education subgroups were approximately 500 kcal/d, the calorie equivalent of consuming 3.3 cans of beer (40.0 oz), 5.0 glasses of wine (20.0 oz), or 5 shots of liquor (7.5 oz).13,35 These estimates exceed the DGA recommended daily intakes of 1 drink per day for women and 2 drinks per day for men and are suggestive of heavy drinking on any given day. 1 Results from the current study update previous findings and indicate a comparatively low proportion of drinkers coupled with exceedingly high per consumer calorie intakes in most recent years. These findings suggest that excess alcoholic beverage consumption may persist among low SES subgroups in the US.

The contribution from wine intake was greater among those in the oldest age group compared to the youngest age group and among women as compared to men across survey years. These results extend upon previous studies in which wine intake in the US has been associated with female sex. 13,17 Although older adults consumed more wine than younger adults and women consumed more wine than men, calories consumed from wine did not exceed those of beer and liquor/mixed drinks until the 2009–2012 period. These are novel findings regarding those ≥ 60 years of age as older age has previously been linked with liquor consumption in the US. 17,24 Shifts towards wine consumption among women and older adults could be attributed to popular press and socio-cultural norms emphasizing the health benefits of wine consumption over the past decade. 48–50 These findings underscore the need for monitoring trends in alcoholic beverage intake by beverage preference across socio-demographic subpopulations of US adults.

Finally, the adjusted proportion of drinkers on any given day in 2009–2012 reported in this study (23.8%) is much lower than the annual prevalence of drinking reported by the National Institutes of Health for 2012–2103 (70.7%). 51 Methodological differences in quantifying annual prevalence as compared to consumption on any given day require different interpretations and, according to current study findings, lead to differing conclusions. 52 When the ALQ was used to categorize alcoholic beverage consumers, the percentage of adults who reported drinking at least 1 drink in the past year increased from 73.0% (2003–2006) to 79.9 % (2009–2012). In comparison the proportion of drinkers on any given day, determined from the 24-hr recall, remained stable from 2003–2006 to 2009–2012. Estimates from the ALQ indicate that the change in the 12-month prevalence of drinking was significantly different for older as compared to younger adults and men and NHB as compared to women and Mex-Am, respectively. Shifts were not observed in the proportion of consumers on any given day. Drinkers captured by the ALQ may not have reported an alcoholic beverage on the day of 24-hr recall. As such, the prevalence of drinking over the last 12 months is not an appropriate proxy for alcoholic beverage consumption on any given day but does indicate that occasional drinking has increased more than national averages for drinking on any day.

Strengths and limitations

There are some potential limitations to this study. Most notable is the difference in dietary data collection methodologies used across years. The day 1 dietary data collection location for the two CSFII datasets was based on an in-home interview the NHANES dietary interview was in a mobile examination center. It is possible the presence of other family members impacted reporting of alcoholic beverage intake on the CFSII surveys. No bridging study has been undertaken to understand the impact of these two methods or the introduction of multiple-pass methodology and automated software between the CSFII and the more recent NHANES surveys. 53 Furthermore, the use of 1 day of 24-hr recall may not capture less frequent drinkers who drink occasionally throughout the year resulting in selection bias for intakes of all consumers of alcoholic beverages in the US. Regarding energy intake estimates, the mean of a group’s 1 day intake can yield a reasonable estimate of the group’s mean usual intake, if the recalls are collected on all days of the week and seasons of the year, as is the case with NHANES. 12,14 Future work is needed to characterize less frequent drinking subpopulations as compared to those drinking frequently enough to be captured by 24-hr recall. An additional limitation of the current study is the inability to examine age, period and cohort effects. It is possible that the increases observed may, in part, be due to an earlier cohort with higher drinking levels aging over time. 54 The results of this study are strengthened by the use of nationally representative detailed 24 hour recall data which collects information on alcoholic beverage type. Moreover, these findings support previous studies that have reported increases in per capita per day alcoholic beverage consumption and calculated alcoholic beverage expenditures in the US over the past 30 years. 10,11,55

Conclusions

These results highlight the increase over the last two decades in alcoholic beverage intake, particularly in the proportion consuming and also the amount per consumer reported using nationally representative dietary intake data. In 2009–2012 the overall per consumer intake on any given day was equivalent to 3.7 glasses of wine (18.4 oz), 2.9 cans of beer (35.3 oz) or 4.4 shots of liquor (6.6 oz of liquor). 13 These estimates indicate heavy drinking levels among respondents who reported consumption of alcoholic beverages on the day of recall. 56 Furthermore, the percentage contribution of alcoholic beverage intake to total energy intake among consumers on any given day has increased from 14.0% to 17.2% over the last 20 years. Excess alcoholic beverage intake is associated with a range of adverse health consequences and future work is needed to understand the causes and consequences of increasing trends in alcoholic beverage calories in the US.

Supplementary Material

Practice Implications.

What is the current knowledge on this topic?

Calories per capita per day from alcoholic beverages and heavy drinking episodes have increased among US adults during the past 20 years. Liquor preference has been associated with older age; wine preference has been linked to female sex.

How does this research add to knowledge on this topic?

There has been an increase in the proportion consuming alcohol on any given day. When drinking occurs, calorie intakes indicate heavy drinking levels among most subgroups. A recent shift towards wine among women and older adults occurred.

How might this knowledge impact current dietetics practice?

Additional emphasis on alcoholic beverage intake as part of dietary assessment may be warranted. In practice, dietetics professionals may need novel nutrition counseling strategies for addressing alcoholic beverage consumption.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study comes from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF 67506, 68793,70017, 71837), the National Institutes of Health (NIH R01DK098072), a National Institutes of Health National Research Service Award (NIH-NRSA 2T32DK007686-21), and the Carolina Population Center (CPC 5 R24 HD050924). Thank you to Dr. Phil Bardsley for exceptional assistance with data management and programming and Ms. Frances L. Dancy for administrative assistance.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure:

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Lauren Butler, Email: lauren_butler@unc.edu.

Jennifer M. Poti, Email: poti@unc.edu.

Barry M. Popkin, Email: popkin@unc.edu.

References

- 1.United States Department of Agriculture and United States Department of Health and Human Services. [Accessed June 13, 2013];Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010. (7). 2010 Dec; http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/dga2010/dietaryguidelines2010.pdf.

- 2.Breslow RA, Guenther PM, Juan W, Graubard BI. Alcoholic beverage consumption, nutrient intakes, and diet quality in the US adult population, 1999–2006. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010 Apr;110(4):551–562. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breslow RA, Mukamal KJ. Measuring the burden--current and future research trends: results from the NIAAA Expert Panel on Alcohol and Chronic Disease Epidemiology. Alcohol research : current reviews. 2013;35(2):250–259. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Traversy G, Chaput J-P. Alcohol consumption and obesity: an update. Current obesity reports. 2015;4(1):122–130. doi: 10.1007/s13679-014-0129-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sayon-Orea C, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Bes-Rastrollo M. Alcohol consumption and body weight: a systematic review. Nutrition reviews. 2011;69(8):419–431. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slattery ML, McDonald A, Bild DE, et al. Associations of body fat and its distribution with dietary intake, physical activity, alcohol, and smoking in blacks and whites. american Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1992;55(5):943–949. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/55.5.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sluik D, Bezemer R, Sierksma A, Feskens E. Alcoholic Beverage Preference and Dietary Habits: A Systematic Literature Review. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition. 2015 doi: 10.1080/10408398.2013.841118. just-accepted. 00-00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gunzerath L, Hewitt BG, Li TK, Warren KR. Alcohol research: past, present, and future. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2011;1216(1):1–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peterkin B. Dietary guidelines for Americans. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 1990;90(12):1725–1727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duffey KJ, Popkin BM. Shifts in patterns and consumption of beverages between 1965 and 2002. Obesity. 2007;15(11):2739–2747. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Popkin BM. Patterns of beverage use across the lifecycle. Physiology & Behavior. 2010;100(1):4–9. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guenther P, Bowman S, Goldman J. Alcoholic beverage consumption by adults 21 years and over in the United States: Results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003–2006. Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion (CNPP); 2010. [Accessed June 13, 2013]. http://www.cnpp.usda.gov/sites/default/files/dietary_guidelines_for_americans/AlcoholicBeveragesConsumption.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nielsen SJKB, Fakhouri T, Ogden CL. Calories consumed from alcoholic beverages by U.S. adults, 2007–2010. [Accessed June 13, 2013];NCHS Data Brief, no 110. 2012 http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db110.htm#citation. [PubMed]

- 14.Tooze JA, Midthune D, Dodd KW, et al. A new statistical method for estimating the usual intake of episodically consumed foods with application to their distribution. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2006;106(10):1575–1587. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolf A, Bray GA, Popkin BM. A short history of beverages and how our body treats them. obesity reviews. 2008;9(2):151–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Cancer Institute National Institutes of Health and United States Department of Health and Human Services. [Accessed June 23, 2013];Measurement Error Webinar Series: Webinar 3: Estimating usual intake distributions for dietary components consumed episodically. 2013 http://appliedresearch.cancer.gov/measurementerror/

- 17.McCann S, Sempos C, Freudenheim J, et al. Alcoholic beverage preference and characteristics of drinkers and nondrinkers in western New York (United States) Nutrition, Metabolism, and Cardiovascular Diseases. 2003;13(1):2–11. doi: 10.1016/s0939-4753(03)80162-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barefoot JC, Gronbaek M, Feaganes JR, McPherson RS, Williams RB, Siegler IC. Alcoholic beverage preference, diet, and health habits in the UNC Alumni Heart Study. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2002;76(2):466–472. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.2.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bendsen NT, Christensen R, Bartels EM, et al. Is beer consumption related to measures of abdominal and general obesity? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrition reviews. 2013;71(2):67–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2012.00548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dawson DA, Grant BF, Chou SP, Pickering RP. Subgroup variation in U.S. drinking patterns: results of the 1992 national longitudinal alcohol epidemiologic study. Journal of substance abuse. 1995;7(3):331–344. doi: 10.1016/0899-3289(95)90026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kerr WC, Patterson D, Greenfield TK. Differences in the measured alcohol content of drinks between black, white and Hispanic men and women in a US national sample. Addiction. 2009;104(9):1503–1511. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02579.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haughwout SP, LaVallee RA, Castle MI-JP. [Accessed June 23, 2013];SURVEILLANCE REPORT# 102 APPARENT PER CAPITA ALCOHOL CONSUMPTION: NATIONAL, STATE, AND REGIONAL TRENDS, 1977–2013. 2015 http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/surveillance85/CONS06.pdf.

- 23.Organization WH. Global status report on alcohol and health-2014. World Health Organization; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klatsky AL, Armstrong MA, Kipp H. Correlates of alcoholic beverage preference: traits of persons who choose wine, liquor or beer. British journal of addiction. 1990 Oct;85(10):1279–1289. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1990.tb01604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paschall M, Lipton RI. Wine preference and related health determinants in a US national sample of young adults. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2005;78(3):339–344. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klein H, Pittman DJ. Drinker prototypes in American society. Journal of substance abuse. 1990;2(3):299–316. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(10)80003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haines PS, Hama MY, Guilkey DK, Popkin BM. Weekend eating in the United States is linked with greater energy, fat, and alcohol intake. Obesity research. 2003;11(8):945–949. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Breslow RA, Chen CM, Graubard BI, Jacobovits T, Kant AK. Diets of drinkers on drinking and nondrinking days: NHANES 2003–2008. American journal of clinical nutrition. 2013;97(95):1068–1075. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.050161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kerr WC, Greenfield TK, Tujague J. Estimates of the mean alcohol concentration of the spirits, wine, and beer sold in the United States and per capita consumption: 1950 to 2002. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2006;30(9):1583–1591. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. [Accessed June 23, 2013];Continuing Survey of Food Intakes by Individuals, 1989–1991. 2013 http://www.ars.usda.gov/Services/docs.htm?docid=14393.

- 31.United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. [Accessed June 23, 2013];Differences Between Current and Original Release of CSFII/DHKS 1994–96, 1998 Dataset and Documentation. 2013 http://www.ars.usda.gov/SP2UserFiles/Place/12355000/pdf/csfii9498_documentationupdated.pdf#data_collection.

- 32.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. [Accessed June 23, 2013];National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data, 2005–2006 2006. 2006 http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/nhanes2005-2006/nhanes05_06.htm.

- 33.National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data, 2009–2010. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. [Accessed June 23, 2013]. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/nhanes2009-2010/nhanes09_10.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 34. [Accessed January 22, 2015];National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data, 2011–2012. 2015 http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/nhanes2011-2012/overview_g.htm.

- 35.United States Department of Agriculture ARS. USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 26. Beltsville, Maryland 20705: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, National Nutrient, Beltsville Human Nutrition Research Center, Nutrient Data Laboratory; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 36.National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data, 2003–2004. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Department of Health and Human Services; 2004. [Accessed June 23, 2013]. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes_03_04/DIETARY_MEC.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anand J, Raper NR, Tong A. Quality assurance during data processing of food and nutrient intakes. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 2006;19:S86–S90. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. [Accessed October 29, 2015];National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; 2005 – 2006 Data Documentation, Codebook, and Frequencies; Dietary Interview - Individual Foods, First Day (DR1IFF_D) 2005–2006 http://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2005-2006/DR1IFF_D.htm#References.

- 39.UCLA Statistical Consulting Group, UCLA Institute for Digital Research and Education. Statistical Computing Seminars. [Accessed March 12, 2015];Applied Survey Data Analysis in Stata 9. 2015 http://www.ats.ucla.edu/stat/stata/seminars/applied_svy_stata9/default.htm.

- 40.Questionnaire Files. Alcohol Use [Data, Docs, Questionnaire] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics; 2006. [Accessed June 12, 2014]. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003–2004. http://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2003-2004/ALQ_C.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Questionnaire Files. Alcohol Use [Data, Docs, Questionnaire (ages 20+)] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics; 2008. [Accessed June 12, 2014]. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005–2006. http://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2005-2006/ALQ_D.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Questionnaire Files. Alcohol Use [Data, Docs, Questionnaire (ages 20+)] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics; 2012. [Accessed June 12, 2014]. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2009–2010. http://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2009-2010/ALQ_F.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Questionnaire Files. Alcohol Use [Data, Docs, Questionnaire] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics; 2013. [Accessed June 12, 2014]. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2011–2012. http://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2011-2012/ALQ_G.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chartier KCR. Ethnicity and health disparities in alcohol research. Alcohol Research & Health. 2010;33(1–2):152–160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Caetano R, Clark CL, Tam T. Alcohol consumption among racial/ethnic minorities. Alcohol Health and Research World. 1998;22(4):233–241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Keyes KM, Miech R. Age, period, and cohort effects in heavy episodic drinking in the US from 1985 to 2009. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2013;132(1):140–148. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Caetano R, Clark CL. Trends in alcohol consumption patterns among whites, blacks and Hispanics: 1984 and 1995. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1998;59(6):659–668. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.The American Heart Association. [Accessed March 2, 2015];Alcohol and Heart Health. 2015 http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/GettingHealthy/NutritionCenter/HealthyEating/Alcohol-and-Heart-Health_UCM_305173_Article.jsp.

- 49.Artero A, Artero A, Tarín JJ, Cano A. The impact of moderate wine consumption on health. Maturitas. 2015;80(1):3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Giacosa A, Barale R, Bavaresco L, et al. MEDITERRANEAN WAY OF DRINKING AND LONGEVITY. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition. 2014 doi: 10.1080/10408398.2012.747484. just-accepted. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) [Accessed May 03, 2015];Table 2.41B—Alcohol Use in Lifetime, Past Year, and Past Month among Persons Aged 18 or Older, by Demographic Characteristics: Percentages, 2012 and 2013. 2015 Mar; http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabsPDFWHTML2013/Web/HTML/NSDUH-DetTabsSect2peTabs1to42-2013.htm#tab2.41b.

- 52.Livingstone MB, Black AE. Markers of the validity of reported energy intake. Journal of Nutrition. 2003;133(Suppl 3):895S–920S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.3.895S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guenther PM, Perloff BP, Vizioli TL., Jr Separating fact from artifact in changes in nutrient intake over time. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 1994;94(3):270–275. doi: 10.1016/0002-8223(94)90367-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Keyes KM, Li G, Hasin DS. Birth cohort effects and gender differences in alcohol epidemiology: a review and synthesis. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2011;35(12):2101–2112. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01562.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. [Accessed June 23, 2014];Table 4: Alcoholic beverages: Total expenditures. 2013 http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/food-expenditures.aspx.

- 56.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed August 8, 2015];Alcohol and Public Health: Frequently Asked Questions. 2014 http://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/faqs.htm#bingeDrinking.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.