Abstract

Background

Serotonin plays an important role in treatment of depression. We evaluated the clinical correlates of plasma serotonin levels in depressed patients before and after treatment.

Methods

Study sample comprised of 40 patients diagnosed on ICD-10 diagnostic criteria, and an equal number of healthy matched controls. Subjects were evaluated on Beck's Depression Inventory (BDI) and Suicide Ideation Scale (SIS), before and after the treatment. Blood samples were collected from all the cases and controls before starting the antidepressant medication with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI's). Serum serotonin levels were measured before and after treatment.

Result

Significant differences in scores before and after the intervention on BDI, SIS and serotonin levels of cases and controls (p<.000) were noted. Correlation between the serum serotonin levels before and after the treatment, and between the rating scales did not reveal significant association (p > 0.05). Patients with suicidal intentions had lower levels of serotonin. The scores changed after intervention.

Conclusion

Treatment with SSRI's had shown significant changes in clinical conditions. However these changes did not relate significantly with serum serotonin levels.

Key Words: Serotonin, Depression, Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

Introduction

Serotonin is one of the most powerful neurotransmitters, with widespread effects. Psychiatric disorders including depression, anxiety, aggression, compulsive behavior, substance abuse, bulimia, seasonal affective disorder, childhood hyperactivity, mania, hyper sexuality, schizophrenia, and behavioral disorders have been associated with impaired central serotonin function. In 1965, Joseph Schildkraut put forth the hypothesis that depression was associated with low levels of norepinephrine [1, 2]. In subsequent years, there were numerous attempts to identify reproducible neurochemical alterations in the nervous systems of patients diagnosed with depression [3]. Serotonin (5-HT; 5-hydroxytryptamine) occurs naturally in the body. In the periphery, serotonin acts both as a gastrointestinal regulating agent and a modulator of blood vessel tone. Only 2% of the body's serotonin is found in the brain as a neurotransmitter [4]. As a neurotransmitter, serotonin is involved in the modulation of motor function, pain perception, appetite and outflow from the sympathetic nervous system [5].

Historically, Hippocrates was the first to describe melancholia (depression) as a condition associated with “aversion to food, despondency, sleeplessness, irritability and restlessness” [6]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has ranked depression as fourth in a list of most urgent problems worldwide [7].

Etiologically, depression is a neurobiological disorder associated with derangements in neuro-chemical, neuroendocrine and neuro-immunological functions. The possibility that peripheral abnormalities in serotonin metabolism occur in melancholic patients has been investigated by the study of serotonin content of various body fluids including cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), plasma and platelets. Studies have shown that free serotonin is greatly raised in stressed mammals [8]. The concentration of synaptic serotonin is controlled directly by its reuptake into the pre-synaptic terminal therefore drugs blocking serotonin transport have been successfully used for the treatment of depression. The mode of action of these antidepressant drugs on their direct target, the serotonin transport protein and possible regulatory mechanisms in alleviation of depression, though investigated both neurobiologically and clinically over the years is still not fully understood [9]. Low CSF concentration of the serum metabolites 5 HIAA is associated with higher lifetime aggressivity, impulsivity and greater suicidal intent in patients with major depressive disorders [10]. However the clinical correlates of low plasma serotonin levels have not been studied. 5-HT hypothesis of major depression has been formulated in three distinct ways. First a deficit in serotonergic activity is a proximate cause of depression. Second a deficit in serotonergic activity is important as a vulnerability factor in major depression. Third, (now of historical interest only) increased vulnerability to major depression to enhanced serotonergic activity. Most new (as well as older) antidepressants inhibit the re-uptake of serotonin from the synapse and alter 5-HTt protein and mRNA levels. This study attempts to evaluate serotonin levels in depressed patients and identify depressed patients who would respond preferentially to SSRI's amongst Indian population. We studied the clinical correlates of plasma serotonin level in depressed patients before and after the treatment with SSRI's and correlation of plasma serotonin levels with rating scales in depression.

Material and Methods

The study was undertaken at a large urban tertiary care centre with an independent 60 bedded General Hospital Psychiatric Unit (GHPU) providing both inpatient and outpatient services. The sample comprised of 40 patients diagnosed on ICD-10 diagnostic criteria for depressive disorders which included mild / moderate / severe depressive episode cases and recurrent depressive disorders along with an equal number of healthy individuals matched for age, sex and marital status. The control group was free from any comorbid physical or psychiatric illnesses. The following exclusion criteria were used for cases and controls:

-

1.

Patients diagnosed as bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder, substance induced mood disorder and mood disorder due to general medical condition.

-

2.

Patients currently on antidepressant medications.

-

3.

Individuals with a history of acute myocardial infarction in the preceding six months, proinflammatory states and infections.

-

4.

Cases of treatment resistant depression.

The sociodemographic data and the findings of physical examination, MSE and relevant investigations were recorded on a specially designed proforma. Beck's Depression Inventory (BDI) [11] and Suicide Ideation Scale (SIS) [12] were administered to all cases and controls to quantify the severity of depression. The inventory was administered before and after therapy to cases and mean scores were calculated. Blood samples were collected from all the cases and controls before starting the antidepressant medication with any of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI's) (fluoxetine, sertraline, citalopram, and paroxetine) in adequate doses.

The blood was collected by venepuncture into vacutainer's and transferred to pre-rinsed plastic tubes. Tubes were then centrifuged at 4500 × g for 10 minutes to obtain platelet free plasma. Separated serum was kept in deep freezer at -20 degree centigrade. Serum serotonin levels was then calculated by ELISA method. The test was repeated after six months of treatment and recovery. The assessor was blind to the sample of patients and control. The mean (SD) serum levels of serotonin were calculated.

Results

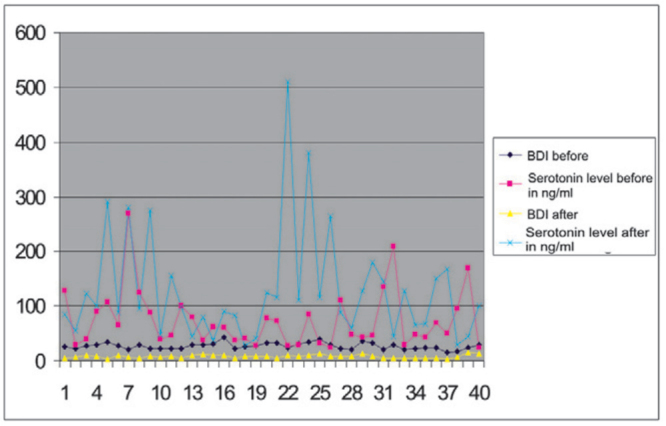

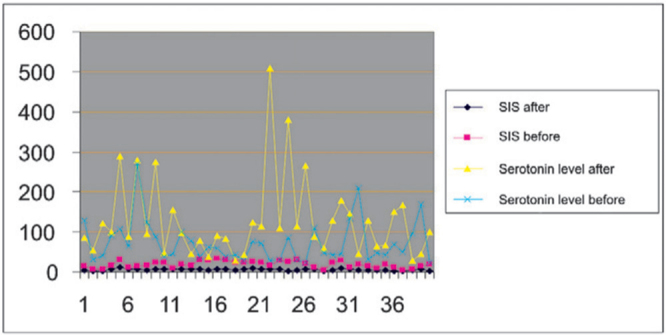

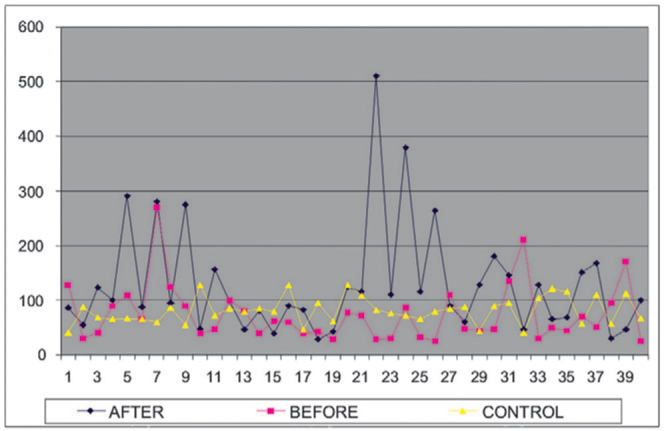

Assessment of cases was carried out by means of clinical interview and psychiatric rating scales (BDI and SIS). The sociodemographic characteristics revealed homogeneity of sample. Minimum age of cases was 21 years and maximum 60 years. The study and control groups were well matched (Table 1). Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test was applied to evaluate the difference in the mean scores before and after the intervention with SSRIs. There was a statistically significant difference between the mean scores before and after the intervention (p<0.00). The scores reduced from 27 to 7.5 and a shift of patients from moderate level of depression to normal level on BDI was seen. Percentages of patients in various degrees of depression are reflected in Table 2. A total of 62.5% cases were present in moderate to severe category of depression. There was significant reduction in percentage of patients after treatment. Of 32.5% patients in extremely severe level of depression, all responded to the treatment and score fell to zero. This implies severity being reduced after treatment (Table 2, Fig. 1). Statistically significant difference on BSI scale before and after the intervention at p<0.00 (Table 3, Fig. 2) was noted. Mean serotonin levels before and after the intervention (p<0.05) increased from mean of 73.75 (ng/ml) to 127.93 (ng/ml) (Table 4, Fig. 3). There was no significant correlation but a negative trend between scores on suicide ideation scale and levels of serotonin was noted i.e. increase in serotonin level decreases scores on suicide ideation scale. This association was not statistically significant. Significant correlation between level of serotonin and scores on depression does not exist but a negative trend was seen i.e. low serotonin levels before treatment was associated with high BDI score.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic variables of cases and controls

| Socio-demographic details | Groups | Cases (n=40) | Control (n=40) | Level of significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education | 10th std. & above | 32 | 35 | df = 1 χ2 = 0.83 |

| Below 10th std. | 08 | 05 | p > 0.05 (NS) | |

| Marital status | Married | 32 | 30 | df = 1χ2 = 0.28 |

| Unmarried | 08 | 10 | p > 0.05 (NS) | |

| Age groups | 20-29 years | 14 | 17 | mean age (34.68 yrs) |

| 30-39 years | 13 | 10 | SD −10.18 | |

| 40-49 years | 10 | 09 | χ2 = 0.88 | |

| 50-60 years | 03 | 04 | p > 0.05 (NS) |

Table 2.

BDI: Effect of treatment on depression scores

| Scores (0-38) | Before therapy (n=40) | After therapy (n=40) | Control (n=40) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal (0-9) | 00 | 28 (70%) | 40 |

| Mild to moderate (10-18) | 02 (5%) | 12 (30%) | |

| Moderate to severe (19-29) | 25 (62.5%) | 00 | |

| Extremely severe (30 >) | 13 (32.5%) | 00 | |

| Mean (Range) | 27 (15-43) | 7.5 (4-20) | 7.1 (4-8) |

| BDI after – BDI before | |||

| Z | −5.516 | ||

| Asymp. Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | ||

Fig. 1.

Beck's Depression Scale: Effect of treatment on depression scores (controls were given Beck's Depression Scale only at baseline).

Table 3.

SIS: Effect of treatment on suicide ideation score

| Scores (0-38) | Before therapy (n=40) | After therapy (n=40) | Control (n=40) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal (0-9) | 06 (15%) | 39 (97.5%) | 40 |

| Mild to moderate (10-19) | 17 (42.5%) | 01 (2.5%) | |

| Moderate to severe (20-29) | 12 (30%) | 00 | |

| Extremely severe (30>) | 05 (12.5%) | 00 | |

| Mean (Range) | 18 (4-33) | 5.75 (2-11) | 2.0 (0-2) |

| Suicidal ideation scale score before and after | |||

| Z | −5.513 | ||

| Asymp. Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | ||

Fig. 2.

Shows changes in the scores of suicide ideation scale with corresponding changes in serum serotonin levels (ng/ml) before and after treatment.

Table 4.

Comparison of serum serotonin levels (ng/ml)

| Serotonin levels | Mean | Difference of mean | t | df | Sig | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | ng/ml | 80.87 | 7.12 | 0.72 | 39 | p=.476 |

| Before intervention | ng/ml | 73.75 | ||||

| After intervention | ng/ml | 127.92 | 54.17 | 3.07 | 39 | p=0.004 |

| Before intervention | ng/ml | 73.75 |

Fig. 3.

Changes in the serum serotonin levels (ng/ml) before and after the intervention along with controls.

Discussion

In our study treatment with SSRI's changed the clinical profile of patients and the scores of BDI and SIS scales. However the relationship of serotonin levels vis a vis decrease in depression and the scores on other rating scales did not reveal statistically significant difference, which is in agreement with other studies [13]. On psychiatric rating scales, 30% (12/40) patients had depressive scores. In 20% of patients, serotonin levels which were on a higher side, declined after the treatment. What is worth mentioning here is that findings on rating scales did not show increase in the same cases (Fig. 3). This finding highlights that there is no direct relationship with serotonin and depression. Low levels of serotonin in cases with higher scores on depression and suicide ideation has been documented in literature which was also seen in this study. However the severity changed after the SSRI's were introduced and there was a significant difference between the two groups. Correlation was computed to understand the relationship between serotonin levels and depression before and after the treatment. Levels of serotonin before treatment along with the scores on depression inventory showed a weak correlation. Low serotonin level is associated with higher score on BDI, which was not significant at statistical level. Whether this reduction is because of serotonin or other confounding variables is difficult to comment. There is a significant reduction in the scores and increase of serotonin levels after the treatment. The demonstrated efficacy of SSRIs cannot be used as primary evidence for serotonergic dysfunction in the pathophysiology of these disorders [14]. Before treatment also the correlation was weak. Serotonin is an independent variable in depression and probably the sample size did dilute the findings The fact that FDA has approved SSRI's for eight separate psychiatric disorders, ranging from social anxiety disorder to obsessive-compulsive disorder to premenstrual dysphoric disorder shows that, the serotonin hypothesis is applicable not just for depression, but also for some of these other diagnostic categories. Thus, for the serotonin hypothesis to be correct as currently presumed, serotonin regulation would need to be the cause (and remedy) for each of these disorders [15]. This is improbable, and no one has yet proposed a cogent theory explaining how a singular putative neurochemical abnormality could result in so many widely differing behavioral manifestations. Studies have shown that free serotonin is raised in stressed mammals and severely ill humans. The same parameter is normal or slightly lowered in dysthymic and endogenous depressed humans. Low CSF concentration of 5 HIAA has been associated with higher lifetime aggressiveness, impulsiveness and greater suicidal intent in patients with major depressive disorders [10]. Reviewing these studies, the chairman of the German Medical Board and colleagues stated, “Reported associations of subgroups of suicidal behavior (e.g. violent suicide attempts) with low CSF–5HIAA (serotonin) concentrations are likely to represent somewhat premature translations of findings from studies that have flaws in methodology” [20]. 20% of the index cases show higher serum serotonin level concentration before than after the treatment, which substantiates the argument that in depression besides serotonin other neurotransmitters are also involved. Some of these cases did not show adequate response to the treatment as one would have expected if depression was indeed due to the deficiency of serotonin. Brain serotonin levels as a predictor of suicide has been the subject of intense research scrutiny over the past several years, with scientists trying to find easily accessible markers so that the neurotransmitter's levels might someday be readily measured in clinical settings. Attempts were also made to induce depression by depleting serotonin levels, but these experiments reaped no consistent results [17]. Likewise, researchers found that huge increases in brain serotonin, arrived at by administering high-doses of L-tryptophan failed to show relief in depression, which underscored the fact that serotonin deficiency is not the only cause. With the proof of serotonin deficiency in any mental disorder lacking, the claimed efficacy of SSRI's is often cited as indirect support for the serotonin hypothesis. Yet, this ‘reasoning backward’ (exjuvantibus line of reasoning i.e., reasoning “backwards”) to make assumptions about disease causation based on the response of the disease to a treatment, is logically problematic. The fact that aspirin cures headaches does not prove that headaches are due to low levels of aspirin in the brain! Serotonin researchers from the US National Institute of Mental Health Laboratory of Clinical Science clearly state, the demonstrated efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors cannot be used as primary evidence for serotonergic dysfunction in the pathophysiology of these disorders [18]. The hypothesis of increased vulnerability to major depression due to enhanced serotonergic activity can take solace in the present study where 20% of cases had increased serotonergic activity yet manifested with depression and treatment with SSRI's showed reduction in the serum serotonin levels. The role of serotonin in depression is thus a matter of debate. Findings of the present study are in agreement with this assumption that backward logic is not applicable. It challenges the basic assumption of low levels of serotonin being responsible for depression and response to treatment related with levels of serotonin being low. Research has demonstrated that class-wide SSRI advertising has expanded the size of the antidepressant market [16, 18] and SSRI's are now among the best-selling drugs in medical practice. The present study has shown the beneficial effect of SSRI's in improving clinical picture supposedly influencing/acting on other receptors/neurotransmitter levels as well. Although much has been researched about serotonergic dysfunction in major depression since 1987, it is clear that there are no simple answers to the questions whether altered 5-HT activity is directly related to the pathogenesis or pathophysiology of major depression or whether it acts as a vulnerability factor.

The present study being a pioneer study in the services, reiterates that serotonin though implicated in depression, is an independent factor. There are other factors which influence the outcome. For e.g. 20% of the cases had high levels of plasma serotonin in the beginning suggesting thereby, that in these patients neurotransmitters other than serotonin may have been responsible for the depressive symptoms. Comparison between baseline psychological assessment before and after treatment has revealed significant differences in severity of depression, severity of suicide ideation and hopelessness along with serum serotonin levels. There was no significant correlation but a negative trend was observed between scores on suicide ideation scale and levels of serotonin. Patients of depression with suicide ideation appear to be responding to treatment with SSRI's. Serum serotonin testing by nanotechnology methods gives accurate estimation of serotonin levels. Thus a larger study will help in generalizing the results.

Conflicts of Interest

This study has been funded by research grants from the Office of DGAFMS.

Intellectual Contribution of Authors

Study Concept : Brig D Saldanha

Drafting & Manuscript Revision : Brig D Saldanha, Maj N Kumar

Statistical Analysis : Surg Capt VSSR Ryali, K Srivastava, Surg Capt AA Pawar

Study Supervision : Surg Capt VSSR Ryali, Maj N Kumar, K Srivastava, Surg Capt AA Pawar

References

- 1.Schildkraut JJ. The catecholamine hypothesis of affective disorders: A review of supporting evidence. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1965;7:524–533. doi: 10.1176/jnp.7.4.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schloss P, Williams DC. The serotonin transporter: a primary target for antidepressant drugs Biochemistry Department University of Dublin, Trinity College Ireland. J Psychopharmacol. 1998;12(2):115–1521. doi: 10.1177/026988119801200201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jaffe R. Tryptophan Update: Helpful Adjunct and Innocent Bystander. J of Nutrition Medicine. 1994;4:133–139. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skop B, Finkelstein J, Mareth T, Magoon M, Brown T. An over the counter cold remedy & vascular disease. Am J Emerg Med. 1994;12:646–648. doi: 10.1016/0735-6757(94)90031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mills KC. Serotonin syndrome. Am Fam Physician. 1995;52:1475–1482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parker G. Melancholia. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1066. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akiskal HS. Mood Disorders: Historical introduction and conceptual overview. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, editors. Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. 8th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; New York: 2005. pp. 559–575. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lechin F, Van der Dijs B, Benaim M. Stress versus depression. Prog Neuro Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 1996;20:899–950. doi: 10.1016/0278-5846(96)00075-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leonard BE. Evidence for a biochemical lesion in depression. Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61:12–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Placidi GP, Oquendo MA, Malone KM, Huang YY, Ellis SP, Mann JJ. Aggressivity, suicide attempts, and depression; relationship to cerebrospinal fluid monoamine metabolite levels. Biol psychiatry. 2001;50:783–791. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01170-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman A. Assessment of suicidal intention: The scale for suicide ideation. J Consult Clin Psychology. 1979;47:343–352. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.47.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mann JJ, McBride PA, Anderson GM, Mieczkowski TA. Platelet and whole blood serotonin content in depressed inpatients: correlations with acute and life-time psychopathology. Biol Psychiatry. 1992;32:243–257. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(92)90106-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murphy DL, Andrews AM, Wichems CH, Li Q, Tohda M, Greenberg B. Brain serotonin neurotransmission: An overview and update with emphasis on serotonin subsystem heterogeneity, multiple receptors, interactions with other neurotransmitter systems, and consequent implications for understanding the actions of serotonergic drugs. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:4–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hypericum Depression Trial Study Group Effect of Hypericum perforatum (St John's wort) in major depressive disorder: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;287:1807–1814. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.14.1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.International Marketing Services Year-end U.S. Prescription and sales information and commentary. International Marketing Services Health Available: Health; Fairfield. (Connecticut): 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roggenbach J, Müller-Oerlinghausen B, Franke L. Suicidality, impulsivity and aggression-Is there a link to 5HIAA concentration in the cerebrospinal fluid.c. Psychiatry Res. 2002;113:193–206. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(02)00230-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murphy DL, Andrews AM, Wichems CH. Brain serotonin neurotransmission: An overview and update with emphasis on serotonin subsystem heterogeneity, multiple receptors, interactions with other neurotransmitter systems, and consequent implications for understanding the actions of serotonergic drugs. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:4–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]