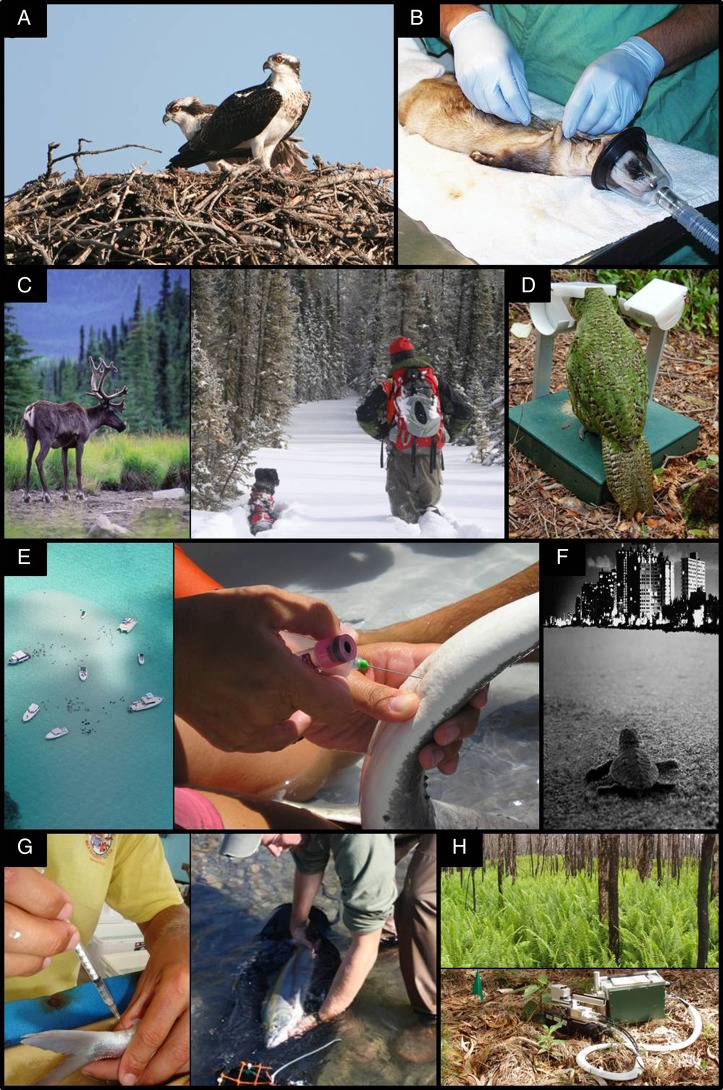

Figure 1:

Conservation physiology successes cover a diversity of taxa, ecosystems, landscape scales and physiological systems. For example: (A) Birds of prey, such as osprey, have rebounded following regulations on DDT. (B) Plague is being combated in the endangered black-footed ferret via a targeted vaccination programme. (C) Caribou and wolf populations are being effectively managed via physiological monitoring of scat. In the right photo, a scat detection dog locates samples for subsequent physiological processing. (D) Nutrition programmes support successful breeding in the critically endangered kakapo. (E) Ecotourism feeding practices are regulated for stingrays in the Cayman Islands. In the right photo, a blood sample is obtained from the underside of the tail to monitor multiple physiological traits. (F) Sensory physiology has informed shoreline lighting regulations for nesting sea turtles. (G) Physiological monitoring of incidentally-captured fishes can be accomplished through blood sampling (left photo), and recovery chambers have been designed that decrease the stress associated with by-catch in salmonids (right photo). (H) Physiological studies have identified native species that tolerate fire caused by exotic species (top panel) and recruit under low light conditions in heavily invaded forests (bottom panel) in Hawaii Volcanoes National Park. Photograph credits: Randy Holland (A); United States Geological Survey National Wildlife Health Center (B); Wayne Sawchuk and Samuel Wasser (C); Kakapo Recovery (D); Christina Semeniuk (E); Sea Turtle Conservancy (F); Cory Suski and Jude Isabella (G); and Jennifer Funk (H).