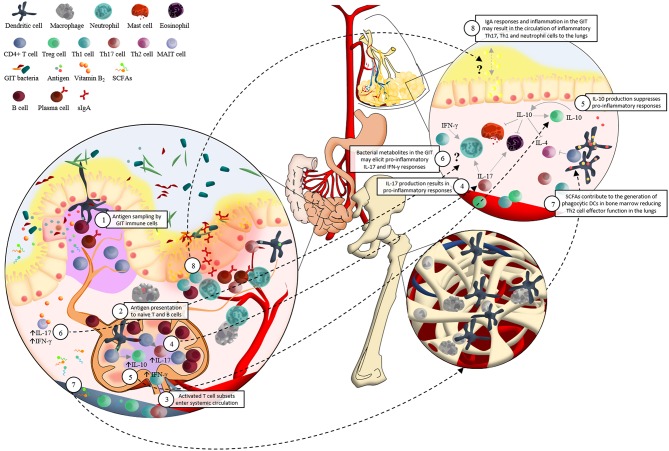

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the potential immunological interaction between the gastrointestinal tract microbiota and the development of asthma. 1. Dendritic cells (DCs) sample antigen in the lamina propria (LP) and Peyer's patches (PP) of the small intestine; and by extending their dendrites into the intestinal lumen. 2. The interactions between DCs and microbial associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) allow DCs to present antigen to naïve lymphocytes in the mesenteric lymph nodes (mLNs). For example, DCs present epitopes together with major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II and specific immunomodulatory cytokines to naïve CD4+ T cells. This elicits proliferation and activation of various T cell subsets which 3. enter systemic circulation via the efferent lymph, homing to mucosal surfaces inside and outside of the gastrointestinal tract (GIT). 4. TGF-β contributes to the differentiation of Th17 cells, which produce cytokines (such as IL-17) involved in pro-inflammatory responses. 5. IL-12 associated cytokines are responsible for Th1 cell differentiation. This regulates the induction of IL-10, which supresses pro-inflammatory responses. 6. Presentation of vitamin B2, from a wide range of bacteria and fungi via MR1 molecules, to mucosa-associated invariant T (MAIT) cells results in a rapid production of pro-inflammatory Th1/Th17 cytokines. MAIT cells' preferential location in the GIT LP and PP, as well as their pro-inflammatory responses in reaction to bacterial metabolites such as vitamin B2, may support their potential role in asthma pathogenesis via the “gut-lung axis” in a similar manner to what has been proposed for DCs. 7. Circulating short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) contribute to the protection against allergic airway inflammation via enhanced generation of DC precursors in bone marrow, followed by seeding of the lungs with DCs with high phagocytic capacity and limited ability to promote Th2 cell effector function. 8. Localization of inflammatory GIT bacteria in the GIT mucus layer may induce strong IgA responses and chronic local inflammation. An influx of inflammatory Th17, Th1, and neutrophil cells in the GIT could potentially circulate to the lungs where they may contribute to asthma pathogenesis. This hypothesis may be supported by the strong associations found between irritable bowel disease (IBD) and asthma.