Abstract

Background:

Adherence to dietary and medication regimen plays an important role in successful treatment and reduces the negative complications and severity of the disease. Therefore, the present study aimed to investigate the effect of nurse-led telephone follow-up on the level of adherence to dietary and medication regimen among patients after Myocardial Infarction (MI).

Methods:

This non-blinded randomized controlled clinical trial was conducted on 100 elderly patients with MI who had referred to the cardiovascular clinics in Shiraz. Participants were selected and randomly assigned to intervention and control groups using balanced block randomization method. The intervention group received a nurse-led telephone follow-up. The data were collected using a demographic questionnaire, Morisky’s 8-item medication adherence questionnaire, and dietary adherence questionnaire before and three months after the intervention. Data analysis was done by the SPSS statistical software (version 21), using paired t-test for intra-group and Chi-square and t-test for between groups comparisons. Significance level was set at<0.05.

Results:

The results of Chi-square test showed no statistically significant difference between the intervention and control groups with respect to their adherence to dietary and medication regimen before the intervention (P>0.05). However, a statistically significant difference was found between the two groups in this regard after the intervention (P<0.05). The mean differences of dietary and medication adherence scores between pre- and post-tests were significantly different between the two groups. Independent t-test showed these differences (P=0.001).

Conclusion:

The results of the present study confirmed the positive effects of nurse-led telephone follow-up as a method of tele-nursing on improvement of adherence to dietary and medication regimen in the patients with MI.

Trial Registration Number: IRCT201409148505N8

KEYWORDS: Adherence, Follow-up, Myocardial infarction, Nurse

INTRODUCTION

Coronary Artery Diseases (CADs), which have been consistently ranked among the most common Cardiovascular Diseases (CVDs), are the leading cause of mortality and morbidity in both developed and developing countries.1,2 CADs account for 21% of mortality and morbidity worldwide in both men and women.3,4 In Iran, also, CAD is the leading cause of mortality and morbidity and almost 138,000 Iranians die due to such diseases annually. Almost 50% of such deaths occur due to Myocardial Infarction (MI).5 According to the report published by World Health Organization (WHO), approximately 14 million people globally die due to MI. However, recent surgical and pharmaceutical interventions have reduced the mortality resulting from MI. Yet, prognosis of patients with acute MI is still poor.6

Patients’ adherence to treatment regimen, especially dietary and medication regimen, is one of the disease-related behaviors which can predict successful treatment and reduce the severity of the disease and its complications.7 Adherence to treatment regimen is especially of utmost importance in patients with CVDs.8 Patients often have challenge with dietary modifications, especially with heart-healthy dietary pattern, and their adherence to the prescribed regimens not appropriate after discharge.9 Moreover, patients with MI are commonly advised to take lots of medications for long periods of time to reduce the complications, morbidity, and mortality.

Despite health care providers’ advice, medication and dietary adherence is still poor among the patients with MI that can increase the risk of disease recurrence and rehospitalization. Moreover, 48% of all readmission in patients with MI are due to lack of adherence to dietary and medication regimen.10 Accordingly, it is essential for clinicians and caregivers to encourage the patients to adhere to appropriate methods which modify the risk factors of CVDs.11

Nurses also play a vital role in increasing the patients’ adherence to treatment regimen and improvement of their clinical outcomes.10 Furthermore, they can significantly contribute to providing the patients with information about their disease and its symptoms as well as MI-related subjects such as lifestyle, medications, nutrition, physical activities, and stress management which can definitely help them make better decisions about lifestyle modifications in the post-discharge period.12 Therefore, providing patients with training and consultation is highly recommended as an essential part of nursing care.13 Nurses’ optimal selection of the type of nursing education and consultation is of great importance in this regard; it can lead to patients’ adherence to treatment regimen, delay progression of the disease, and reduction of the disease-related complications.14

Nowadays, information and communication technology is widely used to alleviate the limitations of health care systems and for better patient care.15 It seems that electronic management of chronic diseases is an effective method which helps to obtain reliable information, empowers the patients, affects their attitudes and behaviors, and potentially improves their medical conditions.16

Tele-nursing, which is a part of electronic health (e-Health), has provided the possibility to deliver nursing care and conduct nursing practice through communication devices, such as movies, Internet, and telephone, among which telephone is more available and widely used by the majority of individuals.17 It is a very helpful and cost-effective method to assess the patients’ out-of-hour care needs and to reduce the frequency of check-ups.18 Using telephone not only reduces the costs and facilitates access to effective healthcare, but it also improves the relationship between patients and healthcare providers. It can eliminate the barriers associated with time and place, as well.19 Weekly or monthly telephone conversations of nurses with patients and providing consultations can be considered a promising healthcare approach that can increase the positive outcomes of the treatment and improve management of patients’ health conditions.20

Research has shown that telephone-delivered interventions could improve self-efficacy among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.18 It also could significantly decrease emotional distress and improve functional status and mental impression (quality of life) in patients suffering from breast cancer.21,22 Besides, telephone-based interventions could result in clinically important reductions in hospital readmissions among adults with asthma.23 Several studies in Iran have also reported that such interventions could improve the patients’ quality of life after pacemaker implantation,24 reduce readmissions in patients with heart failure,25 reduce glycosylated hemoglobin, and play an effective role in controlling the glycemic level.26 However, no comprehensive studies have been performed in Iran on the use of telephone follow-up interventions for providing healthcare to patients with MI. Therefore, the present study aimed to investigate the effect of nurse-led telephone follow-up on medication and dietary adherence among patients after myocardial infarction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was a non-blinded randomized controlled clinical trial (IRCT201409148505N8). After obtaining approval from the Ethics Committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (Ethics Committee Approval Number: CT-93-7089), we recruited 100 elderly patients with MI who had referred to the cardiovascular clinics affiliated to Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, southwest Iran from June to December 2014.

Based on a similar study conducted by Mok et al. (2013)9 and using MedCalc statistical software (power: 90%, α: 0.05, and loss rate=20%), a 100-subject sample size was determined for the study (50 subjects in each group).

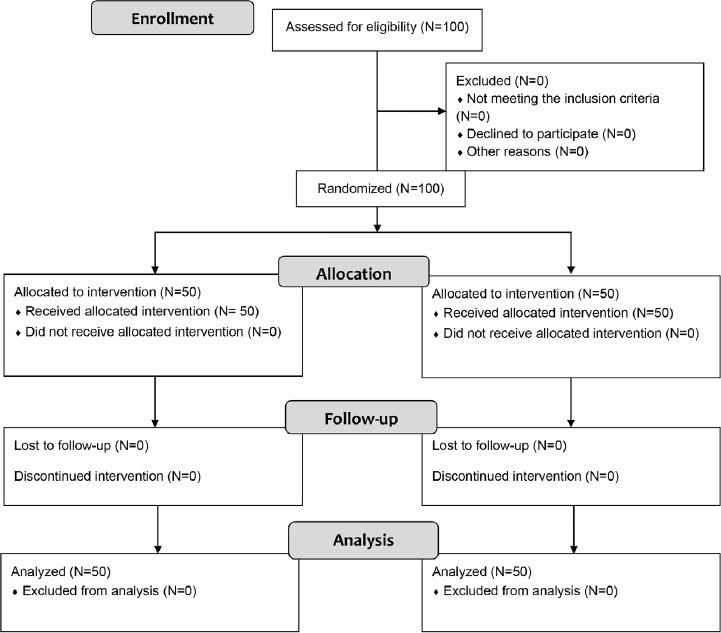

From patients with diagnosis of myocardial infarction referred to heart clinics affiliated to Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, 100 patients who met the inclusion criteria were selected by convenient sampling method. The participants were randomly assigned to an intervention and a control group using block randomization method. To provide balance between the groups and prevent selection bias, a random sequence of 2 or 4 block sizes was applied (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Design and protocol of the study

The inclusion criteria of the study were first-time MI, confirmed diagnosis of MI by a cardiologist, being under treatment, ability to speak and understand Persian, after at least 2 months from the onset of the disease, Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction (LVEF) ≥30%, having access to a telephone, not suffering from any severe and life-threatening diseases (approved by physician), and having ability to perform daily routine activities. On the other hand, the exclusion criteria of the study were unwillingness to participate in the study, not answering the telephone for more than three consecutive times, and need for coronary artery bypass surgery.

After providing the patients with information regarding the study objectives and procedure, their written informed consents were obtained and their anonymity and confidentiality were guaranteed. The data were collected using a demographic questionnaire, Morisky’s 8-item Medication Adherence Questionnaire (MAQ), and dietary adherence questionnaire before and three months after the intervention. Demographic data included age, gender, blood pressure, weight, height, marital status, education level, occupation, smoking status, and history of underlying medical conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia.

Dietary adherence was assessed using dietary adherence questionnaire for patients with MI that is a part of dietary adherence questionnaire for patients with cardiovascular diseases. This self-report questionnaire was developed to assess the patients’ dietary and medication adherence. This questionnaire consisted of 13 items. The total score of the questionnaire could range from 0 to 46, with higher scores reflecting better adherence to the regimen. In addition, scores 0 -15.3, 15.3-30.6, and 30.6- 46 represented poor, intermediate, and high adherence levels, respectively. Ziaee et al. (2011) verified the validity and reliability of the Persian version of the scale by content validity and test-retest methods, respectively (r=0.86).27

Adherence to medication regimen was examined by 8-item MAQ scale. The total score of the scale could range from 0 to 8, with scores <6, 6 to <8, and 8 reflecting low, average, and high levels of adherence, respectively. The scale’s reliability and validity were assessed by Morisky et al. (2008).28 At first, the questionnaire was translated into Persian and its face and content validities were confirmed with corrective feedback from 8 professors in the field of nursing. Besides, its Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was calculated as 0.95.

Initially, the participants’ blood pressure (BP), height, and weight were measured by the researcher. Then, the participants and one of their close relatives with whom they lived were trained by the researcher on the importance of adherence to dietary and medication regimen in a one-hour session.

The participants in the intervention and control groups received a training booklet, attended an initial training session, and received routine healthcare services such as check-up or screenings by the designated physician. Additionally, the participants of the intervention group received a three-month nursing telephone consultation and follow-up. In this study, nurse-led telephone follow-up included phone calls for 12 weeks with patients and providing opportunities for counseling and education about diet, medications and clinical manifestations of myocardial infarction and helping the patients to identify the benefits and barriers of behavioral modifications and encouraging them for observance of treatment regimen.

The researcher’s cell phone number and a call schedule were given to the patients. The schedule included two contacts per week during the first four weeks, one contact per week during the second four weeks, and one contact every two weeks during the third four weeks. The average duration of each call was at least 15 minutes and the researcher was available for contact 24 hours a day in case of any questions or problems.

The content of telephone conversations generally included the researcher’s self-introduction, inquiring about the patient’s general health condition, giving healthcare advice, informing the patients about nutrition and medication, assessing the patients’ level of adherence to dietary and medication regimen, evaluating the behavioral objectives agreed upon by the patients and the researcher, reinforcing health behaviors, terminating the call with the words of encouragement, and arranging the next contact. During the telephone conversation, the researcher emphasized compliance with the plans and agreements made during the training session, evaluated the existing barriers, and proposed possible solutions to the patient’s problems. The researcher also tried to involve the patients’ family members in the process of follow-ups during the telephone contacts. According to similar studies,9,25,26 the questionnaires were completed again by the participants three months after the intervention.

The collected data were analyzed using the SPSS statistical software, version 21. Chi-square and t-test were used to compare demographic variables based on the quantitative or qualitative nature of the variables and to ensure the homogeneity of the groups. Intra-group comparisons were performed by paired t-test whereas independent t-test was used for inter-group comparisons before and after the intervention. The significance level was set at <0.05.

RESULTS

This study was conducted on 100 patients with MI in the age range of 58.31±1.032 years. The majority of the participants were female (54%) and married (84%), and had primary school education. The results of independent t-test and Chi-square test showed no statistically significant difference between the intervention and control groups with respect to quantitative and qualitative demographic characteristics (table 1). In other words, the two groups were homogenous in terms of age, sex, BP, weight, height, marital status, education level, occupation, smoking status, and history of any underlying diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants in intervention and control groups

| Group Variable | Intervention group (N=50) | Control group (N=50) | P value* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | |||

| Sex | Male | 27 | 54% | 19 | 38% | 0.160 |

| Female | 23 | 46% | 31 | 62% | ||

| Marital status | Married | 39 | 78% | 45 | 90% | 0.171 |

| Widowed-Divorced | 11 | 22% | 5 | 10% | ||

| Education level | Primary education | 36 | 72% | 33 | 66% | 0.666 |

| Diploma or higher education | 14 | 28% | 17 | 34% | ||

| Occupational status | Employee | 5 | 10% | 7 | 14% | 0.184 |

| Retired | 15 | 30% | 13 | 26% | ||

| Self-employed | 12 | 24% | 14 | 28% | ||

| Homemaker | 18 | 36% | 16 | 32% | ||

| Characteristics | Mean±SD | Mean±SD | P value** | |||

| Age (Year) | 58.92±9.64 | 57.70±10.64 | 0.140 | |||

| Weight (kg) | 68.46±10.06 | 73.40±11.24 | 0.230 | |||

| Height (cm) | 163.54±8.20 | 165.68±7.84 | 0.186 | |||

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 130.80±14.35 | 129.00±14.32 | 0.146 | |||

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 82.40±7.30 | 80.00±8.63 | 0.137 | |||

Chi-square test;

independent t-test

The results showed no statistically significant difference between the intervention and control groups as to pre-test dietary adherence scores. The results of paired t-test showed no significant difference between the pre-test and post-test mean scores of dietary adherence in the control group (P=0.096). However, a significant difference was observed in the intervention group in this regard (P=0.001). The mean differences of dietary adherence scores between pre- and post-tests were 0.82 (SD=3.14) and 17.46 (SD=56.12) for the control and intervention groups, respectively. The result of independent t-test showed a significant difference between the two groups in this regard (P=0.001) (table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of the intervention and control groups regarding the mean score of adherence to dietary and medication regimen before and after the intervention

| Time Group and variable | Pre-test Mean±SD | Post-test Mean±SD | Mean difference Mean±SD | Paired t-testP value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adherence to dietary regimen | Intervention group | 13.46±7.26 | 30.92±10.86 | 17.46±56.12 | 0.001 |

| Control group | 12.90±5.38 | 13.72±6.63 | 0. 82±3.41 | 0.096 | |

| Between group: P | 0.662 | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||

| Adherence to medication regimen | Intervention group | 3.16±2.43 | 7.24±1.53 | 4.08±0.367 | 0.001 |

| Control group | 2.8±2.49 | 3.14±2.69 | 0.34±0.192 | 0.084 | |

| Between group: P | 0.467 | 0.003 | 0.001 | ||

The results also indicated no significant difference between the intervention and control groups in terms of pre-test mean scores of medication adherence. The results of paired t-test showed no significant difference between the pre-test and post-test of medication adherence scores in the control group (P=0.084), while a significant difference was observed in the intervention group in this regard (P<0.05). The mean differences of pre-test and post-test scores were 4.08 (SD=0.367) and 0.34 (SD=0.192) in the intervention and control groups, respectively. The results of independent t-test showed a significant difference between the two groups in this regard (P=0.001) (table 2).

In the pre-test, the majority of the participants in both groups reported poor dietary adherence level (more than 80%), but in post-test the majority of the patients in the intervention group (62%) reported a high level of dietary adherence while in the control group the majority of patients (82%) still had poor dietary adherence in post-test. The results of Chi-square test showed a statistically significant difference between two groups with respect to their adherence to dietary regimen after the intervention (P<0.001) (table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of the intervention and control groups regarding the level of adherence to dietary and medication regimen before and after the intervention

| Time and group Variable and level of adherence | After intervention | Before intervention | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention group (N=50) F (%) | Control group (N=50) F (%) | Intervention group (N=50) F (%) | Control group (N=50) F (%) | ||

| Adherence to dietary regimen | Poor | 40 (80) | 43 (86) | 5 (10) | 41 (82) |

| Moderate | 7 (14) | 5 (10) | 14 (28) | 7 (14) | |

| Good | 3 (6) | 2 (4) | 31 (62) | 2 (4) | |

| P value | 0.726 | 0.001 | |||

| Adherence to medication regimen | Poor | 37 (74) | 39 (78) | 5 (10) | 36 (72) |

| Moderate | 9 (18) | 6 (12%) | 11 (22) | 8 (16) | |

| Good | 4 (8) | 5 (10) | 34 (68) | 6 (12) | |

| P value | 0.683 | 0.002 | |||

Similarly, the majority of the participants reported a poor medication adherence level in the pre-test, but after the intervention the majority of the patients in the intervention group (68%) reported a high level of medication adherence. No significant improvement was reported by the participants of the control group in this regard. The results of Chi-square test showed a statistically significant difference between the two groups with respect to their adherence to medication regimen after the intervention (P<0.002) (table 3).

Overall, the study findings demonstrated that the level of dietary and medication adherence improved significantly in the participants of the intervention group who had received the nurse-led telephone follow-up intervention.

DISCUSSION

The results of the present study confirmed the positive effects of tele-nursing intervention on improvement of adherence to dietary and medication regimen in the patients with MI. The points of special interest in the results were the changes occurred in the adherence to dietary regimen in the intervention group; their adherence level increased from poor in the pre-test to high in the post-test after receiving the intervention. However, no significant difference was observed between the dietary adherence level in the pre- and post-test phases in the control group.

Likewise, tele-nursing intervention could positively affect the patients’ adherence to medication regimen. The medication adherence level increased from poor in the pre-test to high in the post-test in the intervention group after receiving tele-nursing intervention. However, no significant difference was found between the medication adherence level in the pre- and post-test phases in the control group.

Our findings were supported and confirmed by the results of other studies. One of them reported that tele-nursing follow-up could improve dietary adherence in patients with MI.9 In another study, a twelve-week telephone follow-up intervention resulted in positive changes in post-MI lifestyle.29 A similar study revealed that nurse-led telephone follow-up could improve diabetes diet adherence and decrease glycosylated hemoglobin levels among the patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus.26 Likewise, the results of a study on the patients with psychological disorders revealed that telephone consultation could improve medication adherence and reduce the referral rate to emergency department.30 The results of another study that compared the effects of educational intervention based on adult learning theory with and without tele-nursing on self-management in adult with epilepsy showed that patients who received telephone follow-up in addition to education had a better self-management.31

The effect of nursing follow-up counseling by telephone on blood pressure and self-care behaviors of patients with hypertension was investigated in a clinical trial. The results showed that the intervention had consistently positive effect on the patients’ systolic blood pressure control, but it couldn’t improve the patients’ adherence to treatment and life style modification. Researchers emphasized the necessity of long term and regular follow-up for enhancing the patients’ self-care behaviors in chronic conditions.32

During hospitalization, patients with MI usually do not receive effective trainings on the dietary and medication regimen due to their short-term accessibility. Therefore, they might have inadequate knowledge about the regimen and suffer from lack of self-control and self-confidence in the post-discharge period.6,13 Moreover, disconnection from healthcare centers may increase the risk of poor adherence to medication regimen which, in its own turn, may worsen the symptoms of the disease. Therefore, it is important to provide the patients with training and consultation after discharge.33

Hence, telephone-delivered follow-ups and consultation can be applied as a useful method for self-assessment, monitoring, making decisions, and providing patients with the necessary advice.17,18 On the other hand, it enables the patients to have a better contact with their healthcare providers at times of need.34 Overall, tele-nursing intervention could improve the patients’ adherence to medical regimen and reduce the symptoms of their disease.

Telephone follow-up and consultation create an opportunity to provide need-based trainings for the patients, which is not possible through other training methods such as text messaging. The results of one study showed the effect of sending information to patients with hypertension through short text messages on their BP and compliance with therapy. They observed no significant differences between the intervention and control groups in terms of the mentioned variables after six months.35 Such results could be due to failure in providing face-to-face training, the fixed content of training subjects sent by short message system for all patients, and the fact that such educational messages were not tailored to the patients’ training needs. Hence, short text messages cannot replace a verbal communication since in telephone-delivered consultation healthcare providers talk with patients and answer their questions, but the text messages which are sent to all patients have a fixed content.

Tele-nursing refers to the use of information technology in providing care to patients. It is designed based on the care needs of the patients when a large physical distance exists between the patient and the healthcare provider.17,18 Such method is commonly applied for the patients with chronic diseases or those who live in rural areas with transportation difficulties.

Moreover, constant encouragement and advice given by the nurses to patients and their family members can increase the patients’ independence and self-care skills. Also, establishing a care-based network after discharge can not only solve the patients’ caring problems, but it can also decrease the rate of their referral to medical centers.34 Considering the nurses’ limited time and the tension of the patients admitted to cardiac intensive care units, it may be difficult to provide face-to-face training well. Therefore, applying tele-nursing, which is time- and cost-effective, is highly recommended.

The limitations of the current study were its small sample size and short follow-up period. Therefore, further studies with larger sample sizes and longer follow-up periods are recommended to obtain more evidence on the positive effects of tele-nursing on the patients’ adherence to treatment.

CONCLUSION

As to the prevalence of MI, effects of this disease on individuals’ lives, and importance of adherence to treatment to control and prevent the disease and reduce its symptoms, nurses should find better methods to improve the patients’ adherence to treatment. It can be concluded from the present study findings that tele-nursing could improve and modify adherence to medication and dietary regimen among the patients with MI. It is recommended that health care providers especially nurses use the potentials of tele-nursing for improving the patient’s self-care.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This manuscript was extracted from the thesis written by Ms. Maryam Shaabani for MS. degree in critical care nursing (Grant No. 7089) and financially supported by Vice-Chancellor for Research Affairs of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran. Hereby, the authors would like to thank Ms. A. Keivanshekouh at the Research Improvement Center of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences for improving the use of English in the manuscript. They are also grateful for all the honorable personnel of Imam Reza Clinic and Al-Zahra Heart Hospital and all the people who kindly took part in this investigation.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Muller-Riemenschneider F, Meinhard C, Damm K, et al. Effectiveness of non pharmacological secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. European Journal of Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation. 2010;17:688–700. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e32833a1c95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angermayr L, Melchart D, Linde K. Multifactorial lifestyle interventions in the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus-a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2010;40:49–64. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9206-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hariyati RTS, Sahar J. Perceptions of nursing care for cardiovascular interventions, knowledge on the telehealth and telecardiology in Indonesia. International Journal of Collaborative Research on Internal Medicine & Public Health. 2012;4:116–28. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seef S, Jeppsson A, Stafstrom M. What is killing? People’s knowledge about coronary heart disease, attitude towards prevention and main risk reduction barriers in Ismailia, Egypt (Descriptive cross-sectional study) Pan African Medical Journal. 2013;15:137. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2013.15.137.1628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donyavi T, Holakouie Naieni K, Nedjat S, et al. Socioeconomic status and mortality after acutemyocardial infarction: a study from Iran. International Journal for Equity in Health. 2011;10:9. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-10-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shrestha S, Kuria V. Acute myocardial infarction as a life situation from patients perspective (Literature review) Finland: Seinäjoki University of Applied Sciences; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Masror Roudsari DD, Dabiri Golchin M, Parsa Yekta Z, Haghani H. Relationship between Adherence to Therapeutic Regimen and Health Related Quality of Life in Hypertensive Patients. Iranian Journal of Nursing (IJN) 2013;26:44–54. [In Persian] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams R, Carnethon M, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2009 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2009;119:e21–181. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mok VK, Sit JW, Tsang AS, et al. A controlled trial of a nurse follow-up dietary intervention on maintaining a heart-healthy dietary pattern among patients after myocardial infarction. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2013;28:256–66. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0b013e31824a37b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Albert NM. Improving medication adherence in chronic cardiovascular disease. American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. 2008;28:54–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pang SK, Chang M. Psychosocial correlates of fluid compliance among Chinese hemodialysis patients. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2001;35:691–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ho SE, Hayati Y, Ting CK, et al. Information Needs of Post Myocardial Infarction (MI) Patients: Nurse’s Perception in UniversitiKebangsaan Malaysia Medical Centre (UKMMC) Medicin & Health. 2008;3:281–7. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stolic S, Mitchell M, Wollin J. Nurse-led telephone interventions for people with cardiac disease: A review of the research literature. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2010;9:203–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sabate E. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalmarzi Moghaddam M. Use of information technology and intelligent systems to improve e-Health services The first national conference of student management and new technologies in the health sciences, health and the environment 2009. Tehran (Iran): Faculty of Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pare G, Janna M, Sicott C. Systematic review of home telemonitoring for chronic disease: the evidence base. Journal of American Medicine Inform Association. 2007;14:269–77. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Black JM, Hawks JH. Medical Surgical Nursing. 8th ed. United state of America: Elsevier Saunders; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wong KW, Wong FK, Chan MF. Effect of nurse-intiated telephon follow up on self-efficacy among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2005;49:210–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peck A. Changing the face of standard nursing practice through telehealth and telenursing. Nursing Administration Quarterly. 2005;29:339–43. doi: 10.1097/00006216-200510000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shearer N, Cisar N, Greenberg EA. A telephon-delivered empowerment intervention with patients diagnosed with heart failure. Heart Lung. 2007;30:159–69. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allard NC. Day surgery for breast cancer: effects of a psychoeducational telephone intervention on functional status and emotional distress. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2007;34:133–41. doi: 10.1188/07.ONF.133-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salonen P, Tarkka MT, Kellokumpu-Lehtinen PL, et al. Telephone intervention and quality of life in patients with breast cancer. Cancer Nursing. 2009;32:177–90. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31819b5b65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Donald KJ, McBurney H, Teichtahl H, Irving L. A pilot study of telephone based asthma management. Australian Family Physician. 2008;37:170–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ali-Akbari F, Khalifehzadeh A, Parvin N. The effect of short time telephone follow-up on physical conditions and quality of life in patients after pacemaker implantation. Journal of Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences. 2009;11:23–8. [In Persian] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shojaee A, Nehrir B, Naderi N, Zareyan A. Assessment of the effect of patient’s education and telephone follow up by nurse on readmissions of the patients with heart failure. Iranian Journal of Critical Care Nursing. 2013;6:29–38. [In Persian] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zakerimoghadam M, Bassampour SH, Rajab A, et al. Effect of nurse-led telephone follow ups (Tele-nursing) on diet adherence among type 2 diabetic patients. Hayat. 2008;14:63–71. [In Persian] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heydari A, Ziaee ES, Ebrahimzade S. The frequency of rehospitalization and its contributing factors in patient with cardiovascular disease hospitalized in selected hospitals in Mashhad in 2010. 0fogh-e-Danesh Journal of Gonabad University of Medical Sciences. 2011;17:65–71. [In Persian] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morisky DE, Ang A, Krousel-Wood M, Ward HJ. Predictive validity of a medication adherence measure in an outpatient setting. The Journal of Clinical Hypertention. 2008;10:348–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.07572.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 29.Yan J, You LM, Liu B, et al. The effect of a telephone follow-up intervention on illness perception and lifestyle after myocardial infarction in China: A randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2014;51:844–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cook PF, Emiliozzi S, Waters C, Elhajj D. Effect of telephone counseling on antipsychotic adherence and emergency department utilization. American Journal of Management and Care. 2008;14:841–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bagheri E. Comparison of the effectiveness of educational intervention based on Adult Learning Theory- with and without tele-nursing on self-management in adult with Epilepsy [Thesis] Tehran (Iran): Tehran University of Medical Sciences; 2013. [In Persian] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Faraji M. The effect of sustained nursing consult by telephone (telenursing) on adherence to self-care and blood pressure in hypertensive patient referring to cardiovascular clinic affiliated shiraz university of medical science [Thesis] Shiraz (Iran): Shiraz University of Medical Sciences; 2012. [In Persian] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kumar S, Snooks H. Telenursing. 1st ed. London: Springer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hughes RG. Patient Safety, Telenursing, and Telehealth. In: Schlachta-Fairchild Loretta, Elfrink Victoria, Deickman Andrea., editors. Patient safety and quality: An Evidence-Based handbook for nurses. US Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Contreras EM, Wichmann MF, Guillen VG, et al. Effectiveness of an intervention to provide information to patients with hypertension as short text message and reminders send to their mobile phone (HTA-Alert) Aten Primaria. 2004;34:399–405. doi: 10.1016/S0212-6567(04)78922-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]