Abstract

Background:

Bipolar Mood Disorder (BMD) is a type of mood disorder which is associated with various disabilities. The family members of the patients with BMD experience many difficulties and pressures during the periods of treatment, rehabilitation and recovery and their quality of life (QOL) is threatened. In the present study, we aimed to evaluate the effect of family-centered education on mental health and QOL of families with adolescents suffering from BMD.

Methods:

In this randomized controlled clinical trial performed on 40 families which were mostly mothers of the adolescents with BMD referred to the psychiatric clinics affiliated to Shiraz University of Medical Sciences during 2012-13. They were randomly assigned to intervention and control groups.

Results:

The results of single factor multivariate ANOVA/single-factor multivariate analysis of variance and Bonferroni post hoc tests showed that the interaction between the variables of group and time was significant (P<0.001). The mean of QOL and mental health scores increased in the intervention group, but it decreased in the control group at three measurement time points.

Conclusion:

The study findings confirmed the effectiveness of family-centered psychoeducation program on Mental Health and Quality of life of the families of adolescents with Bipolar Mood Disorder.

Trial Registration Number: IRCT201304202812N15

KEYWORDS: Adolescent, Bipolar mood disorder, Mental health, Psycho-education, Quality of life

INTRODUCTION

Mood disorders are characterized by failure to regulate mood, behaviors and emotion. Individuals with such disorders may experience abnormal mood swings, from depression to happiness.1 World Health Organization (WHO) has described mood disorders as the major health issues of the 21st century.2 Bipolar Mood Disorder (BMD) is a chronic disease, with acute attacks, and has a lifetime prevalence of almost 2% to 4%.3 Such disorder, which is associated with various disabilities, can be detected in the people of every social class and race. BMD is the sixth leading cause of disability worldwide.4 In recent years, more attention has been paid to the diagnosis of BMD in children and adolescents and the rate of diagnosis in such age group has been increased. Moreover, the number of children diagnosed with such disease has doubled in recent 10 years.5 13% to 28% of the patients with BMD have disease onset before the age of 13 years and 50% to 66% before the age of 18 years.5 Miklowitz et al. have conducted several studies focusing on adolescents suffering from such disease and their family since 2001.6 Research has shown that having a family member with a mood disorder affects the whole family and leads to loss of their abilities and adaptability. Such deficiencies, not only cause stress in the family members during the acute attacks, but they also affect the course of the disease.7 In the literature review conducted by Steele et al. (2010), the rate of depression and anxiety in the family members who take care of BMD sufferers has been reported 40% to 55%.8

The family members of such patients experience many difficulties and pressures during the periods of treatment, rehabilitation and recovery. Furthermore, their quality of life (QOL) is threatened and, in some cases, they feel depressed and anxious as well. Hence, managing the disease demands a direct interaction between the patients’ family members and mental health professionals.9 Families of adolescents with BMD, who take care of the patients, often feel isolated in their struggle to cope with the disease and seek help for their children. Therefore, focusing on the patients’ family is considered as a logical starting point since the adolescents live with their primary family who are responsible for taking care of them.6,10 Accordingly, family-focused education is a psycho-educational method and a skills training approach for the families with patients suffering from BMD.11

Family psycho-educational intervention could significantly decrease psychological problems of family caregivers if it is combined with common mental health care.12 Family-focused psycho-education is an effective treatment strategy as its positive effects on children and adolescents with BMD have been proven in the review studies. Family-focused psycho-education is a new approach developed for the families of children with such mood disorder to help them cope with the disease. Research has revealed that not only this type of education has been effective for adults with BMD, but it also could decrease the severity of the disease, improve relationships and increase problem solving skills and adaptability in the families.13

Another study demonstrated that such an intervention could enhance the knowledge and information about the disease in BMD sufferers and their families. During their one-year follow-ups, the researchers observed a decrease in the psychological problems caused by care-giving and high emotional expression.14

Currently, QOL is one of the issues of interest to international communities and researchers. WHO has also paid special attention to the development of health care assessment, beyond its traditional criteria such as mortality and morbidity, to evaluate the influential power of physical and psychological diseases on the ability of performing daily activities.15 The researchers believe that physical health is influenced by psychological growth and mental health promotion is based on the prevention and treatment of emotional stresses. Functioning in other domains of QOL is threatened as the level of mental health decreases.16 Therefore, performing interventions on such patients assists inimproving QOL, accelerating recovery, reducing length of hospital stay and eventually health care costs. Otherwise, reduced mental health can negatively affect QOL and it leads to job loss, family disruption, impaired interpersonal communication, and inability to perform personal, family and social responsibilities.17

Hence, assessing QOL in medical environment can be valuable due to some reasons. The techniques and measurement tools used to assess QOL could provide information which has been neglected or not achieved by traditional analysis of treatment outcomes. Assessing QOL as one part of treatment outcomes helps the clinicians and therapists to realize the slight differences that exist in individuals’ responses to treatment.17 Several studies have also confirmed the effectiveness of community-based interventions, home follow-ups, the role of supportive services, rehabilitation and clinical interventions in the improvement of QOL in the patients.18-20 So far, a few studies have been done on the adolescents with BMD and their families especially in Iran while no study in Iran has focused on the families of the patients with such disorder. Therefore, considering the importance and early onset of BMD and the fact that adolescence is a sensitive period, we aimed to evaluate the effect of family-centered education on mental health and QOL of families with adolescents suffering from BMD referred to medical centers affiliated to Shiraz University of Medical Sciences.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants and Procedures

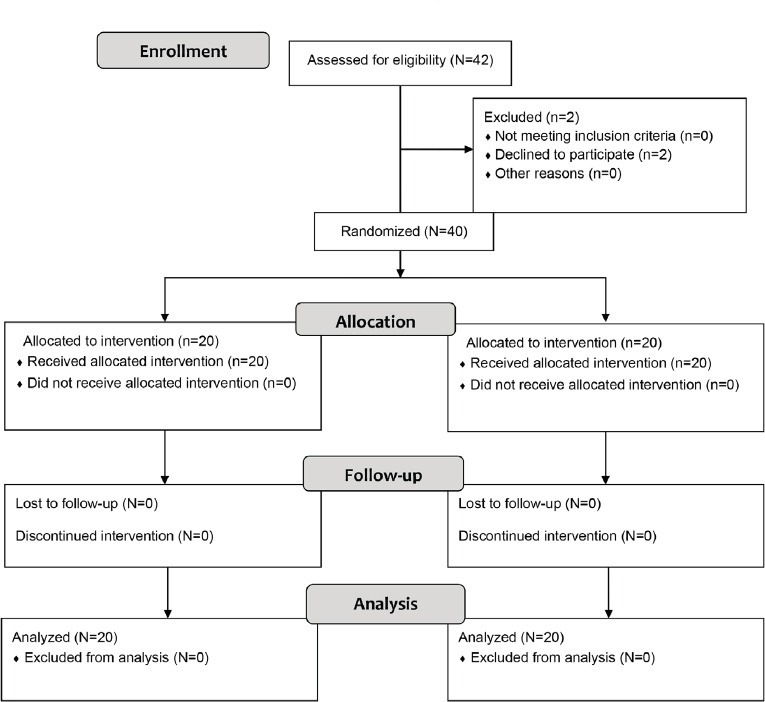

This intervention was performed on 40 families (38 mothers and 2 fathers) of the adolescents with BMD which referred to the psychiatric clinics affiliated to Shiraz University of Medical Sciences during 2012-13. Significant results after the comparison between and within groups shows an adequate sample size (post power analysis >75%). They were randomly assigned to intervention and control groups using block randomization method (block size: 4) (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Design and protocol of the study

Inclusion criteria were having an adolescent aged 12-18 with confirmed diagnosis of BMD by a child and adolescent psychiatrist and lack of any other mental disorders such as mental retardation, epilepsy, schizophrenia, and drug abuse. However, exclusion criteria were unwillingness to participate in the study and absence more than two sessions in the educational program.

Measures

Data were collected using General Health Questionnaire (GHQ), Quality of Life Assessment Questionnaire (Short Form-36) and demographic questionnaire. Demographic data included age, sex and educational level of the adolescent and his/her parents, a history of physical or psychological diseases in the family as well as the number of siblings and birth order. The questionnaires were completed by all participants three times: before, immediately after and one month after the intervention.

The 28-Item version of GHQ (GHQ-28) was developed by Goldberg in 1978. It is a 28-item self-report questionnaire which contains 4 subscales measuring somatic symptoms: anxiety, sleep disorder, social dysfunction, and depression. Each sub-scale contains 7 items and each item is scored on a 4-point Likert scale. The score for each subscale ranges from 0 to 21. The total score, which is obtained by summing up the scores of all subscales, ranges from 0 to 84 with lower scores indicating higher general health status. The reliability and validity of the questionnaire have been assessed in various studies and also estimated and confirmed in Iran. By conducting a pilot study, Yaghoubi estimated the sensitivity and specificity of the questionnaire as 86.5% and 82%, respectively and the cut-off score as 23 based on a Likert-scale scoring. The reliability coefficient of the questionnaire was estimated 88% using test-retest and Cronbach’s alpha. We used the Persian version of CHQ-28, which was translated by Yaghoubi and Palahang (1995), under the supervision of Dr. Barahani, to measure the mental health status in the participants.21

Short form of QOL questionnaire (SF-36) is a 36-item self-report instrument designed to measure health-related QOL across eight dimensions of physical functioning, role limitations caused by physical and emotional problems, bodily pain, general health, mental health, social functioning, emotional problems, energy/fatigue, and health changes. The scores on each dimension range from 0 to 100 with higher scores reflecting higher quality in that dimension. The questionnaire has been extensively used and its validity and reliability were estimated in various studies. Furthermore, internal consistency of the questionnaire was estimated by calculating Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient which was reported between 0.72 and 0.94.22 In Iran, its reliability has been confirmed by Motamed et al. (2001) for Iranian population and Cronbach’s alpha was calculated as 0.87.23

Intervention

This study was approved by Ethics Committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (No CT-92-6718). The research was conducted for two groups (Intervention & Control). All the families in the intervention group participated in a family-centered educational program consisting of six 90-minute sessions per week for 6 weeks. 20 participants in the intervention group were divided into groups of 4 and all of them attended the workshops and received the same content. The educational workshops were directed by a psychiatric nurse and a child and adolescent psychiatry specialist. To provide the intervention protocol, we used Fristad’s educational package (2003) and family educational package on BMD in children and adolescents prepared by Mahmoudi-Gharaei et al. Family educational package included information about the nature and symptoms of mood disorders, therapeutic methods, complications and their course, appropriate interactions with patients, the effect of disease on the family, family’s reactions to the disease, compatibility with the disease, common problems in the family with a patient suffering from mood disorder and problem-solving techniques.24

During the sessions, visual aids equipment was used in order to attract and preserve the attention of the participants. The contents were explained to them using PowerPoint slides, graphs and images related to BMD sufferers. The educational workshops included lectures, presentations and interactive discussions as well as questions and answers. The first 15 minutes of each session was devoted to presenting a summary of the previous session and continued by presenting new contents, the mothers’ questions and their talks about the situations they encountered in this regard. At the end of each session, a training booklet containing the presented contents in that session, and after the end of the 6th session, a booklet containing the key points presented during the whole sessions were given to the participants who attended the educational workshops. The participants of the control group received no intervention.

Data Analysis

The collected data were analyzed using SPSS software, version 16. Chi-square and one-way ANOVA were used to compare demographic variables based on the quantitative or qualitative nature of the variables. Multi-sample repeated measures ANOVA was used to assessthe effect of time and group on the scores of QOL and mental health questionnaires. Single factor multivariate ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc tests were used for within-group comparisons and the independent t-test for between-group comparisons. The significance level was set at α=0.05.

RESULTS

The age range of the participants was 12-18 years and their mean±SD ages were 16±2.7and16.95±1.46 in the intervention and control group, respectively. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in terms of demographic variables. The majority of the participants in both groups had primary education and moderate monthly income level. 47.5% of the mothers reported history of physical diseases and 30% psychological diseases. The results of independent t-test and Chi-square test showed that both groups were matched on demographic variables.

Evaluation of QOL Questionnaire Score

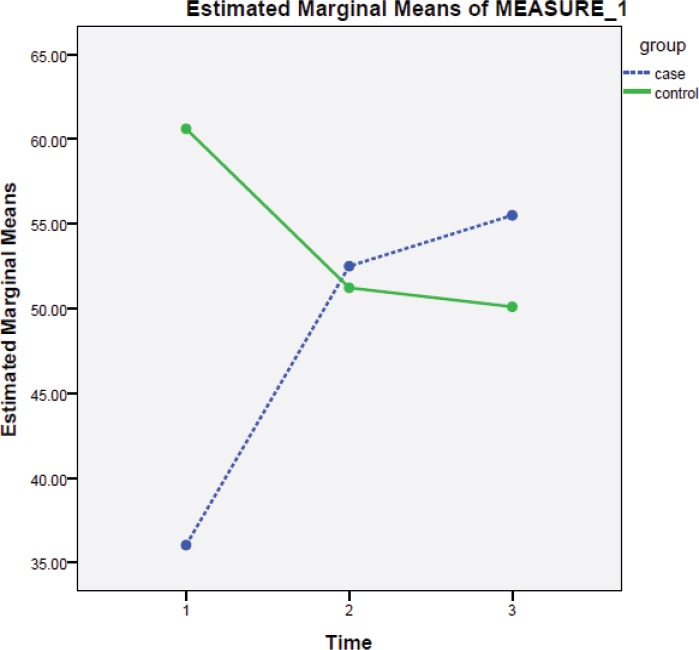

The first part of table 1 displays the mean QOL score before, immediately after and one month after the intervention. The results of multi-sample repeated measure ANOVA for QOL score showed that the interaction between the variables of group and time was significant (P<0.001), reflecting the fact that changes in QOL scores over time were not similar in both groups (figure 2). Therefore, subgroup analyses were used to compare the groups at each time point (between-group analysis) and comparing the responses between time points for each group (within-group analysis).

Table 1.

Comparison of the mean change scores of QOL and mental health between the intervention and control groups before, immediately after and one month after the intervention

| Variables | Groups | Before intervention | Immediately after intervention | One month after intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of life | ||||

| Intervention Control P value |

36.03±16.61 60.61±16.40 <0.001 |

52.50±12.12 51.22±13.58 0.756 |

55.50±11.96 50.10±12.86 0.177 |

|

| Mental health | ||||

| Intervention Control P value |

48.90±11.37 30.52±14.40 <0.001 |

21.90±10.96 40.68±15.09 <0.001 |

17.75±9.05 44.68±14.11 <0.001 |

|

Figure 2.

The mean changes of QOL increased in the intervention group and decreased in the control groups over the time (Time 1: Before intervention, Time 2: Immediately after intervention, Time 3: One month after intervention)

The results of between-group analysis (table 1) indicated that the mean QOL score in the control group was significantly greater than that of the intervention group before the intervention (P<0.001). However, it was not significantly different between the groups immediately after (P=0.756) and one month after the intervention (P=0.177) in this group.

Within-group analysis showed that the mean QOL score increased in the intervention group over the measurement time points (figure 2). However, it decreased at two follow-up time points when compared to the baseline. The results of pairwise comparisons are presented in table 2.

Table 2.

Changes in the mean scores of QOL and mental health before, immediately after and one month after the intervention

| Groups | Variables | Time† | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | QOL | 1 | 0 | <0.001 |

| 2 | <0.001 | |||

| 2 | 1 | 0.002 | ||

| Mental Health | 1 | 0 | <0.001 | |

| 2 | <0.001 | |||

| 2 | 1 | 0.038 | ||

| Control | QOL | 1 | 0 | <0.001 |

| 2 | <0.001 | |||

| 2 | 1 | 0.002 | ||

| Mental Health | 1 | 0 | <0.001 | |

| 2 | <0.001 | |||

| 2 | 1 | 0.038 | ||

| 1 | ||||

The values 0, 1 and 2 in the time column indicate baseline (before), immediately after intervention and one month after the intervention, respectively

Evaluation of Mental Health Questionnaire Score

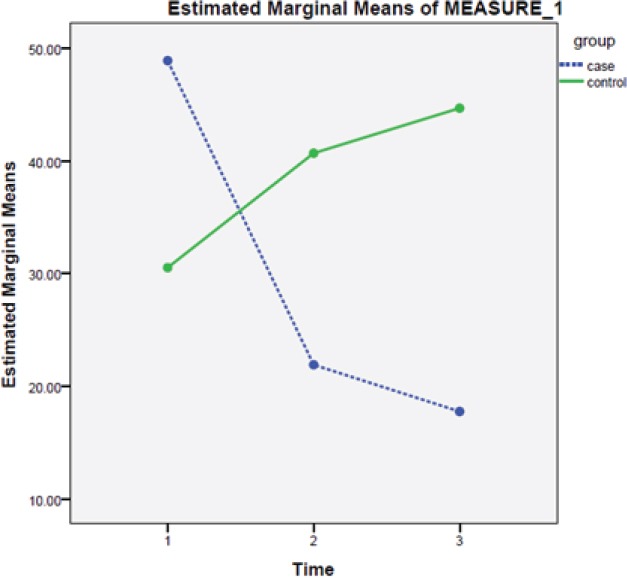

A significant group×time interaction effect indicated that the pattern of changes in the mean mental health were different in the groups (P<0.001). figure 3 illustrates the pattern of changes in the mental health score.

Figure 3.

The mean changes of mental health increased in the intervention group and decreased in the control groups over time

The second part of table 1 shows between-group comparisons in each time point measured. The mean scores in the intervention group (48.90±11.37) were significantly greater than those of the control group (29.65±14.56) (P<0.001). Contrary to the baseline, the mean mental health score was significantly lower for the intervention group both immediately and one month after the intervention when compared to the control group (both P<0.001).

The results of pairwaise comparisons for within-group analysis are presented in table 2. Although it decreased over time in the intervention group, it increased in the control group as time increased (figure 3).

DISCUSSION

Caregivers of BMD sufferers may experience difficulties different from those with other psychological diseases due to cyclic nature of the disease. Also, the patient’s mood tends to fluctuate between two opposite poles of mania and depression. Although the patients may experience recovery phases, the caregivers and family members are constantly concerned about suicidal thoughts and disease recurrence in the patients and changes in the nature of their disease (59%).2

All studies have reported family dysfunction, despair and helplessness in the families living with such patients. In a review article, more than 24 articles about caregivers of the patients with BMD were analyzed, in which 21 articles reported psychiatric distress in the caregivers. Their findings also showed that 46% of caregivers experienced depression.8

Taking care of the patients with such disorder in the family requires appropriate planning. The family members must be qualified enough and have sufficient competencies to handle such task. To achieve this goal, the families need to receive the required trainings on strategies of interacting with the patient, methods of medication use and dealing with the symptoms of the disease and the resulting behaviors.25

Likewise, training the families helps to reduce disease recurrence rate and provide a relaxed and convenient environment for the patients and their family members.26 Our finding also showed that family-centered psycho-education is essential and effective in this regard. The result of another study revealed that family psycho-education could significantly decrease the “sense of pressure” and “family burden” immediately after and one year after the intervention. They also found that depression scores significantly decreased in the patients’ families and relatives who received such intervention.14

Furthermore, we observed a significant difference in the intervention group in terms of the family’s psycho-education before, immediately after and one month after the intervention. QOL is one of the most important areas in the life of the families with psychiatric patients, especially those with BMD, being vulnerable to negative effects. Actually, QOL is characterized as an individual’s specific perception of life satisfaction, physical health, social and family health, hope, etiquette and mental health. In the case of depressive disorders and BMD like other diseases, improving the QOL of the patients and their families is the primary goal of care.18

Another study applied an intervention which included combinations of education about the illness, family support, crisis intervention and problem solving skills training. The results showed that family intervention could improve psychological welfare of the family members. Since life satisfaction and psychological welfare are measures of QOL, these types of interventions could improve QOL in the participants. Dixon’s finding was consistent with ours. In the present study, family-centered education was used in relation with the disease, family support, crisis intervention, interaction with the patient, reaction to the symptoms of the disease and problem solving skills training. Accordingly, QOL improved in our participants in the intervention group immediately after and one month after the intervention. In the control group, however, no significant difference was observed.27

Another study showed that family interventions could improve psychological well-being and comfort, symptoms of the disease, interaction with the patient and family members and eventually QOL since the mentioned factors are all subscales of QOL.28 Researchers believe that physical health can be influenced by psychological growth and mental health promotion is based on prevention and treatment of emotional stress. Functioning in other domains of QOL is threatened as the level of mental health decreases.16

Research findings suggest that children suffering from behavioral disorders and psychiatric diseases can negatively affect their parents. A study on mental health status in family caregivers of the patients with psychiatric disorders revealed that 35% of the respondents reported some sorts of mental health problems.29 Accordingly, in the present study, family-centered education was used to promote mental health in the families of the adolescents with BMD. We observed a statistically significant difference in the intervention group in this regard immediately after and one month after the intervention.

The family caregivers, who take care of a family member with psychiatric disorders, have several needs and nurses can help them meet their needs by proper planning and applying nursing procedures after identifying and prioritizing the needs. All members of the caregiving team are responsible for supporting the families with the patients suffering from psychiatric diseases and satisfying their needs; however, nurses are in a special position and have a key role in this regard since they are the main support of family members in hospitals.18,30

One of the limitations of our study could be small sample size. The number of the recruited participants was few due to less referral of adolescents with BMD and late diagnosis of their disease. Further research with larger sample size could be effective in confirming the results of the present study and making changes in the mean scores of QOL and mental health. A follow-up period of more than one month which is repeated over time is recommended to confirm our results.

CONCLUSION

The study findings confirmed the effectiveness of family-centered psycho-education program on Mental Health and Quality of life of the families of adolescents with bipolar mood disorder. Further research is recommended to be done on families in which the father or mother have BMD and have adolescents with BMD.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The manuscript has been extracted from the Master dissertation of Asyeh Mahmoudi (Grant No: 92-6718). Hereby, the authors thank the vice-chancellery for research of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences for their financial support. Also would like to thank the families who took part in this investigation. The authors would like to thank Nurses of Hafez and Ebne Sina Hospital for their cooperation in this research.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Kaplan & Sadock Synopsis of Psychiatry behavioral Sciences. 10th ed. US: Wolters Kluwer, Lippincott William & Wilkins; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogilive AD, Morant N, Goodwin GM. The burden on informal caregivers of people with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders. 2005;7:25–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2005.00191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Merikangas KR, Akiskal Hs, Angst J, et al. Life time and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:543–52. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bull A. Screening for bipolar disorder in primary care. J Nurse Practitioners. 2010;6:65–6. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stang Paul Frank, Cathy Yood MU, et al. Impact of bipolar disorder: result from a screening study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;9:42–7. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v09n0107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miklowitz DJ, Axelson DA, Birmaher B, et al. Family-focused treatment for adolescents with bipolar disorder: Results of a 2-year randomized trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:1053–61. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.9.1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barry PD. Mental health and mental illness. 7th ed. New York: lippincott; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steele A, Maruyama N, Galynker I. Psychiatric symptoms in caregivers of patients with bipolar disorder: a review. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2010;121:10–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dore G, Romans SE. Impact of bipolar affective disorder on family and partners. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2001;67:147–58. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00450-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Awad AG, Voruganti LN. The burden of schizophernia of caregivers: a review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26:149–62. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200826020-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fristad MA, Gavazzi SM, Mackinaw-Koons B. Family psychoeducation: an adjunctive intervention for children with bipolar disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;53:1000–8. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00186-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hudson P, Quinn K, Kristjanson L, et al. Evaluation of a psycho-educational group programe for family caregivers in home-based palliative care. Palliat Med. 2008;22:270–80. doi: 10.1177/0269216307088187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fristad MA, Goldberg-Arnold JS, Gavazzi SM. Multifamily psychoeducation groups (MFPG) for families of children with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders. 2002;4:254–62. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2002.09073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernhard B, Schaub A, Kümmler P, et al. Impact of cognitive-psychoeducational interventions in bipolar patients and their relatives. European Psychiatry. 2006;21:81–6. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mojarad Kahani A, Ghanbari Hashemabadi BA, Modares Ghoravi M. Effectiveness of a group psychoeducation intervention on quality of life and quality of relationships in families of patients with bipolar disorder. Behavioral Sciences Research. 2012;10:114–23. [In Persian] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bizarri J, Rucci P, Vallotta A, et al. Dual diagnosis and quality of life in patients in treatment for opioid dependence. Substance Use and Misuse. 2005;40:1765–76. doi: 10.1080/10826080500260800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Russo J, Roy-Byrne P, Reeder D, et al. longitudinal assessment of quality of life in acute psychiatric inpatients: Reability and validity. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1997;185:66–75. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199703000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baker F, Jodrey D, Intagliata J. Social support and quality of life of community support clients. Community Ment Health J. 1992;28:397–411. doi: 10.1007/BF00761058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jinnett K, Alexander JA, Ullman E. Case management and quality of life: assessing treatment and outcomes for clients with chronic and persistent mental illness. Health Serv Res. 2001;36:61–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Donnell M, Parker G, Proberts M, et al. A study of client-focused management and consumer advocacy: the Community and Consumer Service Project. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1999;33:684–93. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.1999.00629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ebrahimi A, Moulavi H, Mousavi G, et al. Psychometric Properties and Factor Structure of General HealthQuestionnaire 28 (GHQ-28) in Iranian Psychiatric Patients. Journal of Research in Behavioral Sciences. 2007;5:5–12. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Failde I, Ramos I. Validity and reliability of the Sf-36 Health survey Questionnaire in patients with coronary artery disease. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:359–65. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00175-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Motamed N, Ayatelahi A, Zare N, Sadeghi Hasanabadi A. Reability and validity of SF-36 questionnaire in the staff of Shiraz Medical School 2001. Journal of Zanjan University of Medical Sciences & Health Services. 2002;10:38–46. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mahmoudi Gharaee J, Shahrivar Z, Zarghami F. Psychological training in Bipolar disorder [Internet] Iran (Tehran): Iranian Academy of child & adolescent psychiatry; 2011. [Cited 17 Aug 2015]. Available from: http://www.iacap.ir/fa/entesharat/packages.php . [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boyd MA. Psychiatric Nursing: Contemporary Practice. 3rd ed. China: lippincott, williams&wilkins; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zoladl M, Sharif F, Ghofranipour F, et al. Common lived families with mentaly ill patient: a phenomenological study. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology. 2007;12:67–70. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dixon L. Providing services to families of persons with schizophrenia: present and future. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 1999;2:3–8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-176x(199903)2:1<3::aid-mhp31>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cuijpers P. The effects of family interventions on relatives’ burden: A meta-analysis. Journal of Mental Health. 1999;8:275–85. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gutierrez-Maldonado J, Caqueo-rizar A, Kavanagh DJ. Burden of care and general health in families of patients with schizophrenia. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2005;40:899–904. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0963-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Åstedt-Kurki P, Lehti K, Paunonen M, Paavilainen E. Family member as a hospital patient: sentiments and functioning of the family. International Journal of Nursing Practice. 1999;5:155–63. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-172x.1999.00167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]