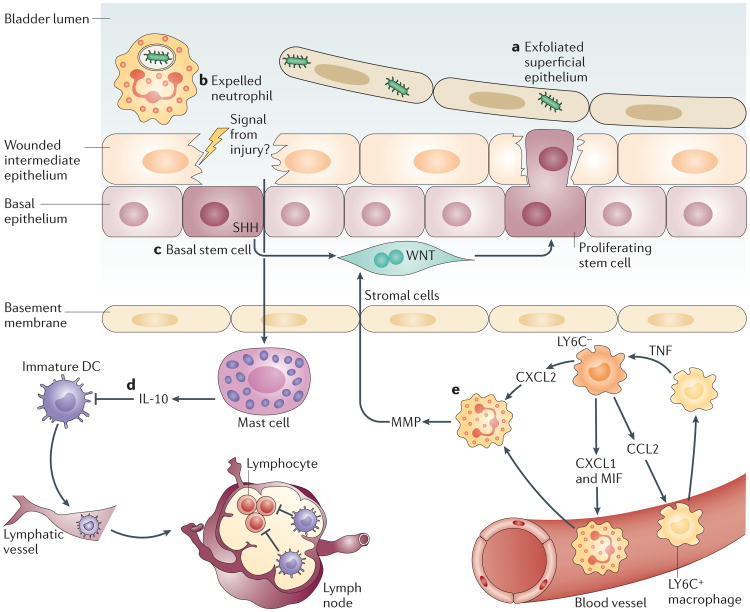

Figure 3. Mechanisms to curtail inflammatory responses in the bladder following infection.

Infections of the superficial epithelium can eventually lead to extensive exfoliation of bladder epithelial cells (part a), resulting in loss of the physical barrier. Each type of immune cell possesses specialized strategies to prevent excessive inflammation and to maintain the tissue integrity. Neutrophils are rapidly expelled into the urine, possibly to reduce the tissue damage from their toxic granules (part b). Local stem cells and stromal cells underneath the intermediate epithelium sense damage to the tissue and initiate a proliferation programme to regenerate the tissue barrier (part c). Local mast cells, which were previously active in mediating a pro-inflammatory immune response, sense the damaged epithelium and switch to mediating anti-inflammatory responses to facilitate regeneration of the epithelium (part d). This switch in activity is achieved by secreting large amount of interleukin-10 (IL-10). Local IL-10 suppresses the activation of dendritic cells (DCs) but not their migration to the iliac lymph nodes. Immature DCs are unable to induce substantial antibody responses in the lymph nodes. Intimate crosstalk between LY6C− and LY6C+ macrophages provides a ‘double-safe’ checkpoint to ensure precise initiation of neutrophil responses (part e): local LY6C− macrophages release CC-chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2), chemokine CXC-chemokine ligand 1 (CXCL1) and macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) to recruit LY6C+ macrophages and neutrophils from the bloodstream. Upon sensing the infection, LY6C+ macrophages secrete tumour necrosis factor (TNF), which acts on local LY6C− macrophages to trigger their production of CXCL2, which induces neutrophils to cross the basal membrane. MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; SHH, sonic hedgehog.