Abstract

HIV-infected men and women who choose to conceive risk infecting their partners. To inform safer conception programs we surveyed HIV risk behavior prior to recent pregnancy amongst South African, HIV-infected women (209) and men (82) recruited from antenatal and antiretroviral clinics, respectively, and reporting an uninfected or unknown-HIV-serostatus pregnancy partner. All participants knew their HIV-positive serostatus prior to the referent pregnancy.

Only 11% of women and 5% of men had planned the pregnancy; 40% of women and 27% of men reported serostatus disclosure to their partner before conception. Knowledge of safer conception strategies was low. Around two-thirds reported consistent condom use, 41% of women and 88% of men reported antiretroviral therapy, and a third of women reported male partner circumcision prior to the referent pregnancy. Seven women (3%) and two men (2%) reported limiting sex without condoms to peak fertility. None reported sperm washing or manual insemination. Safer conception behaviors including HIV-serostatus disclosure, condom use, and ART at the time of conception were not associated with desired pregnancy.

In light of low pregnancy planning and HIV-serostatus disclosure, interventions to improve understandings of serodiscordance and motivate mutual HIV-serostatus disclosure and pregnancy planning are necessary first steps before couples or individuals can implement specific safer conception strategies.

Introduction

Many South African men and women living with HIV want to have children (1–6). The contribution of intended conception to incident HIV infection is likely significant given the high prevalence of stable, heterosexual HIV-serodiscordant couples (1,7–14) and an absence of programs that address periconception transmission.

Several HIV-risk reduction strategies are available for HIV-serodiscordant couples who choose to conceive. Antiretroviral therapy (ART) for the HIV-infected partner regardless of CD4 cell count or clinical stage has been shown to reduce the risk of sexual transmission by as much as 96% (15,16). Antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for the uninfected partner (17–21) reduced HIV acquisition risk by as much as 90% within HIV-serodiscordant couples when adherence was high (22). Limiting sex without condoms to peak fertility may reduce the risk of transmission by reducing the number of exposures required for conception (23–26). In addition, manual insemination (e.g. insemination without sex without condoms) and/or medical male circumcision (MMC) may reduce periconception HIV transmission risk for female-infected couples (27–31). Sperm processing for male-infected serodiscordant couples where spermatozoa (which do not harbor HIV) are separated from the remainder of the seminal fluid and the woman is impregnated via in vitro fertilization or intracytoplasmic sperm injection is becoming standard-of-care in higher-income countries, yet costs and limited availability make this inaccessible for most (32–35). South Africa's national clinical guidelines on fertility planning recommend these risk-reduction strategies (except for PrEP, which is not yet available in the public sector) for serodiscordant couples who want to conceive their own children (36,37). Recent data suggest that these strategies are, however, not widely recommended by South African providers (38) but uptake was high in an implementation project (39).

In our formative qualitative work with HIV-infected individuals reporting uninfected or unknown-serostatus partners in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, men and women reported desires to have children, but did not receive safer conception advice, and risked HIV transmission in order to conceive (4,40). Furthermore a spectrum of pregnancy planning was observed, from explicitly planned to explicitly unintended, with many narratives falling somewhere in between these extremes (41). These data informed a conceptual framework for considering safer conception behavior for HIV-serodiscordant couples (42). We report here on a survey subsequently conducted to quantify periconception risk behavior among a larger sample of individual men and women living with HIV and reporting serodiscordant partners, in order to identify the level of demand and key points of intervention for safer conception programs. To our knowledge, this is the first study to quantify risk behavior for HIV-affected couples during the periconception period.

Methods

Study setting and participant recruitment

Participants were recruited from antenatal care (ANC) or ART clinics at a large, public sector hospital in an urban township outside of Durban, South Africa. ANC clinic HIV prevalence is estimated at 38% for this district within the province of KwaZulu-Natal (43). Women were eligible if they reported HIV-positive serostatus, age 18-45 years and current pregnancy or pregnancy within the past year with a known partner with negative or unknown serostatus. Men were eligible if they were partnered with an enrolled woman, or reported HIV-positive serostatus, age 18 years and over, and pregnancy in the last 3-years of a seronegative or unknown serostatus partner. Due to low reporting of partner pregnancy, timing of partner pregnancy was extended to 3 years for men. To meet eligibility, both men and women must have known their HIV-positive serostatus prior to the referent pregnancy. All eligible participants spoke fluent English or isiZulu, were interested in the study, and provided informed consent. Although we attempted to recruit HIV-negative participants with known HIV-positive partners, we identified only 5 men and 35 women who met these criteria. Due to this small sample, analyses presented here are limited to HIV-positive individuals with partners whose serostatus was reported as negative or unknown. Because only one woman screened referred her male partner, almost all men were recruited from an ART clinic site. Notably, all serostatus data (participant and pregnancy partner) are based on study participant report.

Instruments and procedures

Between May 2011 and June 2012, study participants completed a face-to-face structured interview in a private setting with a research assistant fluent in English and isiZulu. Questionnaire items to address individual determinants of safer conception behavior included sociodemographic variables, HIV history, reproductive history, and HIV knowledge. In order to assess couple-level determinants of safer conception behavior, we administered a measure of sexual relationship power within intimate relationships with decision-making dominance (7 items) and relationship control (15 items) subscales (sexual relationship power scale (SRPS)) (44), and assessed partnership characteristics.

Periconception planning behaviors were defined based on our conceptual framework for safer conception behavior (42) and assessed for the referent pregnancy. We assessed communication with the pregnancy partner about having children and HIV; discussions with health care providers about safer conception; and personal and partner fertility desires and intentions at the time of conception (45,46).

Safer conception behaviors were explored by asking participants to reflect back to their HIV transmission risk behaviors “before you/your partner became pregnant.” Most safer conception recommendations are directed towards mutually-disclosed serodiscordant couples. We assessed HIV-serostatus disclosure as a safer conception behavior given that this is a necessary first step to implementing most safer conception strategies and has been associated with reductions in HIV transmission (47,48). Direct questions were asked about HIV serostatus disclosure to pregnancy partner, knowledge of pregnancy partner HIV serostatus, condom use, MMC, limiting sex without condoms to peak fertility, ART use by the infected partner, sperm washing, and manual insemination. If the participant reported an unknown serostatus partner on the screening questionnaire, but an HIV-positive or HIV-negative partner in the full questionnaire, research assistants attempted to resolve any discrepancies. If this was not resolved during the survey administration, the full questionnaire data were accepted. HIV-serostatus disclosure data reported here are from the full questionnaire, not the screening data form.

Knowledge of HIV transmission risk and risk reduction in the context of having children was assessed by asking participants to answer true or false in response to ten statements developed for this survey. These covered prevention of mother to child transmission, HIV prevention strategies for serodiscordant couples, and HIV prevention strategies specific to safer conception. Items were developed based on formative work with a similar population. Items were pilot tested with local men and women of reproductive age irrespective of HIV-serostatus or partner serostatus in order to insure clarity, relevance, comprehension.

Completion of the interview took just under an hour and participants were reimbursed for their time with 70 South African Rand (approximately US$7 at that time). Enrollment duplication was avoided by collecting unique South African identity numbers and deleting data from repeated questionnaires (n=1).

Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to summarize baseline demographics, partnership characteristics, and proportion of men and women reporting periconception planning and safer conception behaviors.

Multivariate logistic regression was used to evaluate factors associated with each of five safer conception behaviors reported by at least 10% of participants, namely disclosure of HIV serostatus to partner, knowledge of partner HIV serostatus, ART use, condom use most or all of the time, and MMC for female-infected couples. The remaining safer conception behaviors in our conceptual framework such as sperm washing, timing sex to peak fertility, and manual insemination were not reported or reported by too few participants to identify associations. Because the various safer conception behaviors were not independent (e.g. someone who disclosed HIV serostatus to partner was more likely to use condoms), we could not create a simple safer conception score and evaluate the factors associated with carrying out multiple safer conception behaviors. Therefore, we looked at factors associated with each safer conception behavior.

We evaluated the unadjusted relationship between the covariates of interest including individual factors (age, education, income, number of living children, desire for children, years since HIV diagnosis, HIV knowledge score, safer conception knowledge score) and dyadic factors (partnership type, sexual relationship power scale) with each safer conception behavior. Analyses appropriately accounted for the nested outcomes per individual using multivariate logistic regression with estimation via generalized estimating equations. Since the two HIV serostatus disclosure variables (disclosure of HIV serostatus to partner, knowledge of partner HIV serostatus) had effect sizes of similar magnitude for HIV-infected women (no evidence of heterogeneity) we evaluated covariate effects pooled across the HIV-serostatus disclosure outcomes. For the other outcomes for HIV-infected women and all outcomes for HIV-infected men, directions of effect were variable. Factors significant at a p-value < .05 were included in adjusted models. Analyses were completed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Ethics

Ethics approvals were obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee at the University of the Witwatersrand (Johannesburg, South Africa) and the Institutional Review Board at Partners Healthcare (Boston, USA). Permissions to conduct the research were also obtained from the district, provincial and study site authorities.

Results

1. Enrollment

Of 2620 women and 1166 men screened for eligibility, we recruited 209 HIV-positive women and 83 HIV-positive men. Screening data are reported elsewhere (49).

2. Demographics and partnership characteristics

Demographic data are shown in Table 1. Median age of women was 29 years (IQR 25, 33), 86 (41%) had completed grade 12 or beyond, and 56 (27%) were employed (formal or informal). Median number of living children was 1 (IQR 1,2) and years since HIV diagnosis was 3 (IQR 1,5). 159 women (76%) reported that the father of the referent pregnancy was a main partner, 161 (77%) reported that the relationship was ongoing, and 168 (80%) reported that their partner had unknown HIV-serostatus. All but one woman was pregnant at the time of the interview.

Table 1.

Demographic data and partnership characteristics for participants

| HIV-positive women n = 209 Number (%/IQR) | HIV-positive men n = 82 Number (%/IQR) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 29 (25,33) | 34 (31,37) |

| Black South African | 206 (99%) | 82 (99%) |

| Education | ||

| ≤ Some Primary | 8 (4%) | 1(1%) |

| Some secondary | 114 (55%) | 26(32%) |

| Completed secondary school | 81 (39%) | 44(54%) |

| Post-secondary school | 5 (2%) | 11(13%) |

| Employed | 56 (27%) | 61 (74%) |

| Monthly income | ||

| 0-999 ZAR | 59(28%) | -- |

| 1000-1999 ZAR | 69(33%) | 3 (4%) |

| ≥2000 ZAR | 77(37%) | 60 (73%) |

| Missing | 4 (2%) | 19 (23%) |

| Marital status* | ||

| Married/engaged | 43 (21%) | 14 (17%) |

| Long-term partner | 87 (42%) | 43 (52%) |

| Boyfriend/girlfriend | 80 (38%) | 47 (57%) |

| Casual partner | 3 (1%) | 22 (27%) |

| Number of living children | 1 (1,2) | 2 (2,3) |

| Years since HIV diagnosis | 3 (1,5) | 4 (2,6) |

| Pregnancy partner type^ | ||

| Spouse | 34 (16%) | 6 (7%) |

| Main partner | 159 (76%) | 22 (27%) |

| Casual partner | 4 (2%) | 53 (64%) |

| One-time partner | 11 (5%) | 2 (2%) |

| Partner HIV serostatus** | ||

| HIV-uninfected | 41 (20%) | 25 (30%) |

| Unknown | 168 (80%) | 57 (70%) |

| Timing of referent pregnancy# | ||

| Current pregnancy | 208 (99%) | 47 (57%) |

| If not current, age of youngest child (years) | 0.3 | 1 (0.6,2) |

| Relationship on-going | 161 (77%) | 75 (91%) |

>1 partner type identified in the marital status question for 15 women (7%) and 38 men (46%).

Main partner – non-spouse, primary partner, committed relationship. Casual partner – neither main partner, spouse nor one-off partner, not a committed relationship.

Distribution dictated by participant inclusion criteria: infected participants were eligible upon reporting a negative or unknown serostatus partner.

Personal pregnancy for the women, partner pregnancy for the men

Men had a median age of 34 years (IQR 31,37), 55 (67%) had completed grade 12 or above, and 61 (74%) were employed. Median number of living children was 2 (IQR 2,3) and years since HIV diagnosis was 4 (IQR 2,6). 53 men (65%) reported that the pregnancy partner was a casual partner, 75 (91%) reported that the relationship was ongoing, and 57 (70%) reported that their partner had unknown HIV-serostatus. 57% reported a current partner pregnancy. Among those who did not report a current partner pregnancy, the median age of the youngest child was 1 (IQR 0.6-2) years.

3. Safer conception behavior: periconception planning (individual and couple determinants)

Among women, 24 (11%) reported planning the referent pregnancy whereas 67 (32%) reported wanting to be pregnant (the pregnancy was unintended yet desired once confirmed). 108 women (52%) reported that her partner had wanted her to be pregnant. 126 women (60%) discussed having children with her partner sometimes or often whereas 116 (56%) discussed HIV prevention with the pregnancy partner.

Among men, pregnancy planning was also rare (n=4, 5%) whereas 20 (24%) reported wanting the referent pregnancy. Few men (n=9, 11%) reported that their partner wanted the pregnancy. Men were more likely to discuss having children with pregnancy partner (n=42, 51%) than to have a discussion with pregnancy partner about HIV (n=29, 35%).

Only 45 women (22%) and 10 men (12%) reported having ever discussed having children with a health care provider (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Periconception planning behaviors.

This figure shows the percentage of HIV-positive men and women reporting an uninfected or unknown serostatus partner who reported each planning behavior prior to the referent pregnancy.

4. Safer conception behavior: HIV transmission risk behavior

Disclosure of HIV serostatus to the serodiscordant pregnancy partner prior to conception was reported by 83 women (40%) and 22 men (27%). 20% of women (n = 41) and 30% of men (n = 25) reported knowing their partner's HIV serostatus. 41% of women (n = 86) and 88% of men (n = 72) were on ART prior to conception (men were recruited from an ART clinic). 59% of women (n = 124) and 65% of men (n=53) reported condom use most or all of the time prior to pregnancy. 46% of men (n = 38) and 31% of women (n= 65) reported that they or their partner were circumcised (Figure 2). Seven women (3%) and 2 men (2%) reported limiting sex without condoms to the period of peak fertility. No participants reported additional safer conception strategies, such as manual insemination, sperm washing, processing, or any other assisted reproductive technology.

Figure 2. Safer conception behavior.

* Condom use at least most of the time.

This figure shows the percentage of HIV-positive men and women reporting an uninfected or unknown serostatus partner who reported each safer conception behavior prior to the referent pregnancy.

5. Safer conception knowledge and understandings

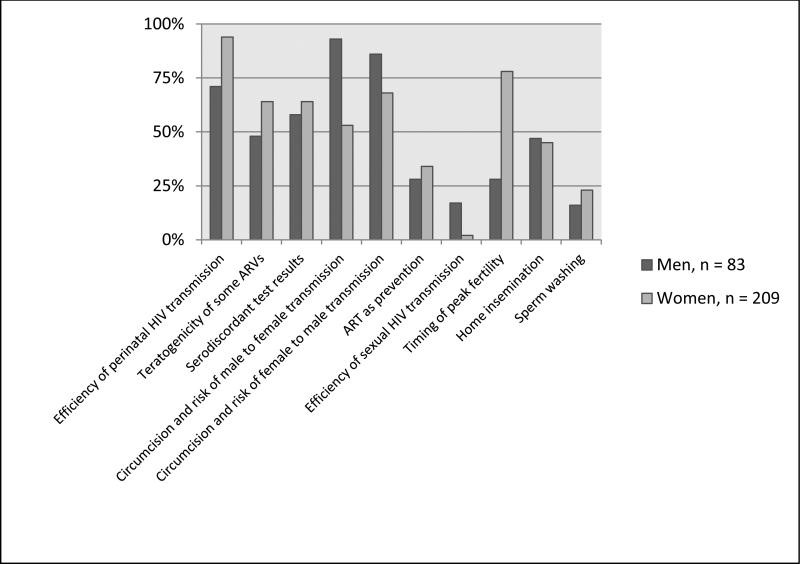

In terms of HIV prevention strategies for serodiscordant couples (for safer conception or otherwise), over two thirds of women and men answered items about the protection offered to men by MMC correctly, however 47% of women (n=98) answered incorrectly that a woman would be fully protected from HIV if her male partner were circumcised. Around one third of women and men answered an item about ART as prevention correctly. Most men answered incorrectly about the timing of peak fertility, less than half the men and women answered correctly about manual insemination and few answered correctly about sperm washing. Notably, 36% of women (n=75) and 43% of men (n=35) thought that a serodiscordant test result between sexual partners was a mistake, which has implications for motivations to implement any HIV transmission risk reduction strategies (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Knowledge of periconception risks and risk reduction strategies.

This figure shows the percentage of HIV-positive men and women reporting an uninfected or unknown serostatus partner who correctly answered true/false items on HIV risk reduction practices.

6. Factors associated with safer conception behaviors

Among women, having a main versus casual partner was associated with 2.88 greater odds of disclosing to their partner (95% CI 1.10-7.53) in adjusted models. Older age (aOR 1.08, 95% CI 1.02-1.14) and more time since HIV diagnosis (aOR 1.13, 95% CI 1.01-1.26) were associated with increased likelihood of ART use. More time since HIV diagnosis was associated with a reduced odds of consistent condom use during sex (0.88 (0.79, 0.98), p = .018). No associations with male partner circumcision were detected (Table 2).

Table 2.

Factors associated with safer conception behaviors reported by women

| HIV-serostatus disclosure* | ART use | Condom use | Male partner circumcised | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aOR (95% CI) | p-value | aOR (95% CI) | p-value | aOR (95% CI) | p-value | aOR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Age (years) | 1.00 (.95, 1.04) | 0.89 | 1.08 (1.02, 1.14) | 0.01 | 1.05 (0.99, 1.11) | 0.10 | 0.97 (0.91 - 1.03) | 0.30 |

| Completed secondary school | .80 (0.48, 1.33) | 0.39 | 1.19 (0.64, 2.21) | 0.58 | 1.43 (0.79, 2.59) | 0.24 | 1.23 (0.66-2.28) | 0.52 |

| Pregnancy desired | 1.64 (0.99, 2.69) | 0.05 | .98 (.51, 1.88) | 0.96 | 0.71 (0.38, 1.31) | 0.27 | .85 (.44, 1.66) | 0.64 |

| Pregnancy partner type (Ref. Casual) | ||||||||

| Spouse | 1.60 (0.71, 3.61) | 0.26 | 1.53 (.46, 5.04) | 0.48 | 1.36 (0.45-4.15) | 0.58 | 0.78 (0.24-2.48) | 0.67 |

| Main | 2.88 (1,10, 7.53) | 0.03 | 3.37 (.87, 13.08) | 0.08 | 1.24 (0.34, 4.52) | 0.74 | 1.19 (.31, 4.52) | 0.80 |

| Years since HIV diagnosis | 1.02 (0.94, 1.12) | 0.62 | 1.13 (1.01, 1.26) | 0.03 | 0.88 (0.79, 0.98) | 0.02 | 1.09 (0.98, 1.22) | 0.12 |

| Safer conception knowledge score | 1.05 (0.91, 1.21) | 0.50 | 1.03 (.84, 1.25) | 0.79 | 1.08 (0.89, 1.31) | 0.44 | 1.14 (.93, 1.40) | 0.20 |

Participant report of disclosure of HIV serostatus to partner and knowledge of partner HIV serostatus. A positive outcome is report of disclosure to partner and knowledge of partner HIV-serostatus.

Covariates that were not significantly associated with behaviors in unadjusted analyses include income, HIV knowledge score, and sexual relationship power.

Among men, having a main versus casual partner type resulted in 19 times greater odds of disclosure to partner (95% CI 4.28-80.67) and 11 times greater odds of knowing the partner's HIV-serostatus (95% CI 2.48- 51.83) in adjusted models. Higher safer conception knowledge was associated with increased odds of knowing partner's serostatus for men (aOR 1.63, 95% CI 1.11-2.40)). Completing high school (aOR 7.49, 95% CI 1.28-43.74) and older age (aOR 1.26, 1.03-1.55) were associated with an increased likelihood of ART use. No factors were significantly associated with condom use (Table 3).

Table 3.

Factors associated with safer conception behaviors reported by men

| HIV-serostatus disclosure to partner | HIV-serostatus disclosure from partner | ART use | Condom use | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aOR (95% CI) | p-value | aOR (95% CI) | p-value | aOR (95% CI) | p-value | aOR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Age (years) | 1.13 (0.93, 1.38) | 0.20 | .89 (.75, 1.07) | 0.21 | 1.26 (1.03, 1.55) | 0.03 | 1.09 (0.96, 1.24) | 0.18 |

| Completed secondary school | 1.50 (0.27, 8.50) | 0.64 | .46 (.09, 2.26) | 0.34 | 7.49 (1.28, 43.74) | 0.03 | 2.25 (0.66, 7.60) | 0.19 |

| Pregnancy desired | 1.13 (.24, 5.35) | 0.88 | 1.14 (0.24, 5.39) | 0.87 | .71 (.11, 4.70) | 0.72 | 1.37 (0.37, 5.02) | 0.63 |

|

Pregnancy partner type (Ref. Casual) Spouse or Main* |

18.59 (4.28, 80.67) | <.001 | 11.33 (2.48, 51.83) | .002 | 1.51 (.22, 10.25) | 0.67 | 1.44 (0.43, 4.83) | 0.55 |

| Years since HIV diagnosis | 1.16 (0.91, 1.49) | 0.24 | 1.45 (1.10, 1.92) | 0.01 | 1.22 (0.82, 1.82) | 0.33 | 0.91 (0.75, 1.11) | 0.36 |

| Safer conception knowledge score | 1.39 (0.95, 2.03) | 0.09 | 1.63 (1.11, 2.40) | 0.01 | .79 (.51, 1.21) | 0.28 | 0.92 (0.71, 1.18) | 0.50 |

Covariates that were not significantly associated with behaviors in unadjusted analyses include income, HIV knowledge score, and sexual relationship power.

Only 6 men reported a spouse. Main partner and spouse were therefore combined into 1 category.

Discussion

In order for serodiscordant couples to reduce periconception risk, partners must understand their mutual HIV serostatus, plan pregnancy, and have knowledge of and access to safer conception strategies (36,42,50). In this sample of HIV-infected men and women with at-risk partners in an HIV-endemic setting, HIV-serostatus disclosure was reported by a minority, most pregnancies were unintended, and understanding of serodiscordance and periconception risk reduction was low. Accordingly, few participants employed safer conception strategies.

The finding that only 40% of women and 27% of men reported disclosure to a pregnancy partner prior to conception is consistent with previous South African research (47,51–54). Bearing in mind that all of our participants knew their HIV-serostatus prior to the referent pregnancy, this level of non-disclosure is noteworthy in a setting where an estimated 20-30% of stable couples are serodiscordant (7,8,55) and where mutual disclosure may lead to reductions in sexual risk behavior (47,48). Disclosure is a complex process mediated by fear of stigma and discrimination (47,48,54,56,57), fears of intimate partner violence (58–60), engagement with HIV care (51,53), concepts of masculinity (61), and relationship communication (57). Promoting positive disclosure beliefs and providing adequate support to couples is an important first step in HIV risk reduction regardless of fertility desires, but is also a critical component of safer conception programming (36). Qualitative data from healthcare providers in this same district describes the challenges non-disclosure creates for providers asked to provide safer conception counseling (62). Initiatives to increase awareness of HIV serostatus and mutual disclosure between sexual partners include provider-initiated HIV counseling and testing (HCT) (63,64), couples HCT (15,65–69) and couples-orientated HCT (70,71). Challenges we faced in recruiting partners to this study may portend limited uptake of couples-based HCT and thus non-couples-based strategies to promote testing and disclosure should remain a priority (58–60). In addition, while most women reported that her pregnancy partner was a spouse or main partner, only a third of men reported that his recent pregnancy was with a spouse or main partner (65% reported with a casual partner.) In our models of factors associated with safer conception behaviors, women and men were more likely to disclose HIV-serostatus to or know the HIV-serostatus of a main or spousal partner compared to a casual partner. Promoting HIV-serostatus disclosure within casual partnerships is an additional challenge.

The prevalence of unintended pregnancy in our sample (reported by 89% of women and 95% of men) was much higher than estimates for the general population (72) and HIV-infected women in South Africa (73,74). This may partially reflect the effect of social desirability bias on expression of fertility desires, which are perceived as incompatible with social expectation (75) or condom-based prevention messages (38,62,76). However data suggest that persons living with HIV experience poor access to contraceptive and other sexual and reproductive health services (5,73,77–79). Improved access to non-judgmental contraceptive counseling and promotion of dual protection (barrier plus other contraceptive method) for the large proportion of HIV-infected men and women who do not desire children is critical to reducing high incidence of unintended pregnancy in this group. These data also highlight the strong presence of male pregnancy desires that were not necessarily compatible with female partner pregnancy desires: 52% of women reported that her partner wanted the referent pregnancy. Increased efforts to engage men in planning for pregnancies with partners are an important piece of optimizing sexual and reproductive health (4,80–82). Efforts to improve women's reproductive autonomy are crucial to reducing unwanted pregnancies as well as HIV acquisition.

Over a third of men and women indicated that a serodiscordant test result between sexual partners must be a mistake. Misconceptions around serodiscordance are well-documented in South Africa (83,84), and commonly lead to the practice of testing by proxy (85), which precludes opportunities to reduce sexual risk-taking that accompanies awareness of serodiscordant status (86). Other concerning knowledge gaps identified included that almost half of women reported that a woman is protected from HIV if her partner is circumcised. This dangerous myth has been reported in qualitative studies in the Western Cape and Tanazania (87–89). Interestingly, a study with university students in KwaZulu-Natal did not observe the same mis-information suggesting that education may overcome this misperception (89). Participants also demonstrated low knowledge of safer conception strategies such as sperm washing, timing sex to peak fertility, manual insemination, and treatment as prevention, thus explaining infrequent safer conception practices. Although our model suggested associations between certain demographic variables and uptake of ART and/or more consistent condom use, the low incidence of planned pregnancy suggests that these factors are incidental, rather than predictors of deliberate safer conception behavior.

ART for the infected partner is recommended by the World Health Organization (16) and arguably the most feasible safer conception strategy for serodiscordant couples in this setting, particularly since it does not rely on serostatus disclosure to an at-risk partner. Since ART requires a prescription, health care providers may be regarded as gatekeepers to both the knowledge and means for treatment as prevention. Yet, in concordance with existing research (2,5,40,90), only 22% of women and 12% men in our sample had ever spoken to a provider about having children. Given the barriers to client-initiated discussions about having children (40), it is incumbent upon providers to pre-emptively assess clients’ fertility intentions. However, despite the existence of national safer conception guidelines (36,37), many providers remain unfamiliar with periconception risk reduction (91) and struggle to balance responsibilities to prevent unnecessary risk exposure and support a client's desire to have a child (48).

This study has several limitations. First, social desirability bias may have influenced responses: all of the data are based on participant report. Second, since our instrument for assessing safer conception knowledge was not previously tested, resultant data may not accurately represent reality; however we feel that the true/false items were more likely to overestimate knowledge, which was low overall. Thirdly, since we recruited men and women from ART and ANC clinics, respectively, demographic and behavioral differences were likely influenced by differential sampling, and not just sex. Fourth, recruitment challenges prevented us from assessing knowledge and behaviors of at-risk seronegative individuals; given that safer conception practices protect the uninfected partner in serodiscordant relationships, the perspective of this population is critical to informing safer conception programs and should be sought in future research. Fifth, some of the confidence intervals for the relationships in our model with men are wide and reflect a lack of precision of the point estimates, largely due to the small sample size.

In conclusion, the high-risk periconception behaviors and low knowledge of safer conception in our sample suggest that public health campaigns are needed in South Africa to help at-risk individuals and couples understand the rationale for safer conception processes, including mutual HIV-serostatus disclosure and pregnancy planning before we can expect uptake of specific safer conception strategies. Our data echo many prior studies describing challenges to HIV-serostatus disclosure and pregnancy planning within sexual partnerships. Our participants had low knowledge of safer conception strategies, but even with excellent knowledge, the same gender norms and stigma factors that impact communication about disclosure and pregnancy planning are expected to influence communication about safer conception practices. Research on safer conception programs must explore how to offer safer conception opportunities to individuals and couples given these challenges. It is possible that once couples understand that serodiscordance is possible, and that a partner can be protected from HIV while allowing for conception, safer conception programs will provide opportunities to promote disclosure and pregnancy planning. However, this remains to be determined. Work in this field tends to focus on safer conception strategies that couples can implement to reduce periconception risk behavior (27,50,62,92–97). However, this paper and work by others (6,40,62,94) suggest that disclosure, pregnancy planning, and communication with partner are critical first steps that must be supported before successful implementation of specific safer conceptions strategies can take place on a broad scale. Mutually-disclosed HIV-serodiscordant couples with well-articulated fertility goals are an important but minority population in South Africa (39,98). There is an evidence-based imperative to integrate comprehensive safer conception counseling into a diverse range of services accessed by persons living with HIV and their partners to improve accessibility of this information (37,99,100) and explore how to maximize acceptability and feasibility.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants and study staff for their contributions to this work.

Lynn Matthews is supported by a K23 award (NIMH 095655) and received funding for this project from the Harvard University CFAR (P30 AI060354), Harvard Global Health Institute, and the Burroughs-Wellcome/American Society for Tropical Medicine and Hygiene Postdoctoral Fellowship in Tropical Infectious Diseases. Additional support was provided by the NIH including K24 awards (NIMH 87227 and 094214) and K23 award (NIMH 096651). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors report no disclosures.

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Cooper D, Harries J, Myer L, Orner P, Bracken H, Zweigenthal V. “Life is still going on”: reproductive intentions among HIV-positive women and men in South Africa. [2014 Mar 25];Soc Sci Med [Internet] 2007 Jul;65(2):274–83. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.019. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17451852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooper D, Moodley J, Zweigenthal V, Bekker L-G, Shah I, Myer L. Fertility intentions and reproductive health care needs of people living with HIV in Cape Town, South Africa: implications for integrating reproductive health and HIV care services. [2014 Mar 25];AIDS Behav [Internet] 2009 Jun;13(Suppl 1):38–46. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9550-1. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19343492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaida A, Laher F, Strathdee SA, Janssen PA, Money D, Hogg RS, et al. Childbearing intentions of HIV-positive women of reproductive age in Soweto, South Africa: the influence of expanding access to HAART in an HIV hyperendemic setting. [2014 Apr 2];Am J Public Health [Internet] 2011 Feb;101(2):350–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.177469. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3020203&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matthews LT, Crankshaw T, Giddy J, Kaida A, Smit J a, Ware NC, et al. Reproductive decision-making and periconception practices among HIV-positive men and women attending HIV services in Durban, South Africa. [2014 Mar 25];AIDS Behav [Internet] 2013 Feb;17(2):461–70. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0068-y. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3560938&tool=pmcentr ez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwartz SR, Mehta SH, Taha TE, Rees HV, Venter F, Black V. High pregnancy intentions and missed opportunities for patient-provider communication about fertility in a South African cohort of HIV-positive women on antiretroviral therapy. [2014 Mar 26];AIDS Behav [Internet] 2012 Jan;16(1):69–78. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9981-3. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21656145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor TN, Mantell JE, Nywagi N, Cishe N, Cooper D. “He lacks his fatherhood”: safer conception technologies and the biological imperative for fatherhood among recently-diagnosed Xhosa-speaking men living with HIV in South Africa. [2014 Apr 28];Cult Health Sex [Internet] 2013 Jan;15(9):1101–14. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2013.809147. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23862770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lurie MN, Williams BG, Zuma K, Mkaya-Mwamburi D, Garnett GP, Sweat MD, et al. Who infects whom? HIV-1 concordance and discordance among migrant and non-migrant couples in South Africa. [2014 Mar 25];AIDS [Internet] 2003 Oct 17;17(15):2245–52. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200310170-00013. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14523282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lingappa JR, Lambdin B, Bukusi EA, Ngure K, Kavuma L, Inambao M, et al. Regional differences in prevalence of HIV-1 discordance in Africa and enrollment of HIV-1 discordant couples into an HIV-1 prevention trial. [2014 Mar 20];PLoS One [Internet] 2008 Jan;3(1):e1411. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001411. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2156103&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Preston-whyte E. Culture, context and behaviour: anthropological perspectives on fertility in Southern Africa. [2014 Mar 25];South African J Demogr [Internet] 1988 Jul;2(1):13–23. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12284169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beyeza-Kashesya J, Ekstrom AM, Kaharuza F, Mirembe F, Neema S, Kulane A. My partner wants a child: a cross-sectional study of the determinants of the desire for children among mutually disclosed sero-discordant couples receiving care in Uganda. BMC Public Health [Internet] 2010 Jan;10:247. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-247. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2877675&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunkle KL, Stephenson R, Karita E, Chomba E, Kayitenkore K, Vwalika C, et al. New heterosexually transmitted HIV infections in married or cohabiting couples in urban Zambia and Rwanda: an analysis of survey and clinical data. [2014 Feb 5];Lancet [Internet] 2008 Jun 28;371(9631):2183–91. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60953-8. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18586173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guthrie BL, de Bruyn G, Farquhar C. HIV-1-discordant couples in sub-Saharan Africa: explanations and implications for high rates of discordancy. Curr HIV Res [Internet] 2007 Jul;5(4):416–29. doi: 10.2174/157016207781023992. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17627505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eyawo O, de Walque D, Ford N, Gakii G, Lester RT, Mills EJ. Lancet Infect Dis [Internet] 11. Vol. 10. Elsevier Ltd; Nov, 2010. [2014 Mar 25]. HIV status in discordant couples in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. pp. 770–7. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20926347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mantell JE, Exner TM, Cooper D, Bai D, Leu C-S, Hoffman S, et al. Pregnancy intent among a sample of recently diagnosed HIV-positive women and men practicing unprotected sex in Cape Town, South Africa. [2015 Feb 13];J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr [Internet] 2014 Dec 1;67(Suppl 4):S202–9. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000369. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=4251915&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization . Guidance on Couples HIV Testing and Counselling Including Antiretroviral Therapy for Treatment and Prevention in Serodiscordant Couples: Recommedations for a Public Health Approach. WHO; Geneva: 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 Infection with Early Antiretroviral Therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(6):493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abdool Karim Q, Abdool Karim SS, Frohlich JA, Grobler AC, Baxter C, Mansoor LE, et al. Effectiveness and safety of tenofovir gel, an antiretroviral microbicide, for the prevention of HIV infection in women. [2014 Mar 19];Science (80− ) [Internet] 2010 Sep 3;329(5996):1168–74. doi: 10.1126/science.1193748. Available from: http://www.sciencemag.org/content/329/5996/1168.abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grant R, Lama J, Anderson P, McMahan V, Liu AY, Vargas L. Preexposure Chemoprophylaxis for HIV Prevention in Men Who Have Sex with Men. [2014 Mar 25];N Engl J Med [Internet] 2010 363(27):2587–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205. Available from: http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1011205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thigpen MC, Kebaabetswe PM, Paxton LA, Smith DK, Rose CE, Segolodi TM, et al. Antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis for heterosexual HIV transmission in Botswana. [2014 Mar 25];N Engl J Med [Internet] 2012 Aug 2;367(5):423–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110711. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22784038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Damme L, Corneli A, Ahmed K, Agot K, Lombaard J, Kapiga S, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. [2014 Mar 25];N Engl J Med [Internet] 2012 Aug 2;367(5):411–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1202614. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3687217&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, Mugo NR, Campbell JD, Wangisi J, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. [2014 Mar 24];N Engl J Med [Internet] 2012 Aug 2;367(5):399–410. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108524. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3770474&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Donnell D, Baeten JM, Bumpus NN, Brantley J, Bangsberg DR, Haberer JE, et al. HIV protective efficacy and correlates of tenofovir blood concentrations in a clinical trial of PrEP for HIV prevention. [2015 Jan 31];J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr [Internet] 2014 Jul 1;66(3):340–8. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000172. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=4059553&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vernazza PL, Graf I, Sonnenberg-Schwan U, Geit M, Meurer A. Preexposure prophylaxis and timed intercourse for HIV-discordant couples willing to conceive a child. [2014 Mar 25];AIDS [Internet] 2011 Oct 23;25(16):2005–8. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834a36d0. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21716070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Del Romero J, Baza B, Rodriguez C, Vera M, Rio I, Hernando V, et al. XIX International AIDS Conference July 22-27 [Internet] AIDS; Washington D.C.: 2012. [2014 Mar 25]. Natural pregnancies in a cohort of HIV-1 serodiscordant couples in Madrid, Spain. 2012. Available from: http://pag.aids2012.org/Abstracts.aspx?AID=16171. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barreiro P, del Romero J, Leal M, Hernando V, Asencio R, de Mendoza C, et al. Natural pregnancies in HIV-serodiscordant couples receiving successful antiretroviral therapy. [2014 Mar 25];J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr [Internet] 2006 Nov 1;43(3):324–6. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000243091.40490.fd. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17003695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taylor S, Whetham J, McInnes C, Charlewood L, Payne E, Kieth T, et al. PrEP-C: A risk reduction strategy for HIV-women with HIV+ partners [#1061].. 19th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Seattle. March 5-8.2012. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mmeje O, Cohen C, Cohen D. Evaluating Safer Conception Options for HIV Serodiscordant Couples (HIV-Infected Female/HIV-Uninfected Male): A Closer Look at Vaginal Insemination. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/587651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bailey RC, Moses S, Parker CB, Agot K, Maclean I, Krieger JN, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in young men in Kisumu, Kenya: a randomised controlled trial. [2014 Mar 21];Lancet [Internet] 2007 Feb 24;369(9562):643–56. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60312-2. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17321310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Auvert B, Taljaard D, Lagarde E, Sobngwi-Tambekou J, Sitta R, Puren A. Randomized, Controlled Intervention Trial of Male Circumcision for Reduction of HIV Infection Risk: The ANRS 1265 Trial. PLOS Med. 2005;2(11):e298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gray RH, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, Makumbi F, Watya S, Nalugoda F, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in men in Rakai, Uganda: a randomised trial. [2014 Mar 25];Lancet [Internet] 2007 Feb 24;369(9562):657–66. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60313-4. Available from: http://www.thelancet.com/journals/a/article/PIIS0140-6736(07)60313-4/fulltext. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wawer MJ, Tobian AAR, Kigozi G, Kong X, Gravitt PE, Serwadda D, et al. Effect of circumcision of HIV-negative men on transmission of human papillomavirus to HIV-negative women: a randomised trial in Rakai, Uganda. [2014 Mar 23];Lancet [Internet] 2011 Jan 15;377(9761):209–18. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61967-8. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3119044&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Semprini AE, Levi-Setti P, Bozzo M, Ravizza M, Taglioretti A, Sulpizio P, et al. Insemination of HIV-negative women with processed semen of HIV-positive partners. [2014 Mar 25];Lancet [Internet] 1992 Nov 28;340(8831):1317–9. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92495-2. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1360037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bujan L, Hollander L, Coudert M, Gilling-Smith C, Vucetich A, Guibert J, et al. Safety and efficacy of sperm washing in HIV-1-serodiscordant couples where the male is infected: results from the European CREAThE network. [2014 Mar 25];AIDS [Internet] 2007 Sep 12;21(14):1909–14. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282703879. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17721098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vitorino RL, Grinsztejn BG, de Andrade CAF, Hökerberg YHM, de Souza CTV, Friedman RK, et al. Systematic review of the effectiveness and safety of assisted reproduction techniques in couples serodiscordant for human immunodeficiency virus where the man is positive. [2014 Mar 25];Fertil Steril [Internet] 2011 Apr;95(5):1684–90. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.01.127. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21324449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lampe MA, Smith DK, Anderson GJE, Edwards AE, Nesheim SR. Achieving safe conception in HIV-discordant couples: the potential role of oral preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in the United States. [2014 Mar 25];Am J Obstet Gynecol [Internet] 2011 Jun;204(6):488.e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.02.026. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21457911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bekker L-G, Black V, Myer L, Rees H, Cooper D, Mall S, et al. Guideline on Safer Conception in Fertile HIV-infected Individuals and Couples. South African J HIV Med. 2011 Jun;:31–44. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Department of Health . National Contraception and Fertility Planning Policy and Service Delivery Guidelines. National Department of Health; Pretoria: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matthews LT, Milford C, Kaida A, Ehrlich MJ, Ng C, Greener R, et al. Lost opportunities to reduce periconception HIV transmission: safer conception counseling by South African providers addresses perinatal but not sexual HIV transmission. [2015 Feb 13];J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr [Internet] 2014 Dec 1;67(Suppl 4):S210–7. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000374. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=4251914&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schwartz SR, Bassett J, Sanne I, Phofa R, Yende N, Van Rie A. Implementation of a safer conception service for HIV-affected couples in South Africa. [2015 Jan 20];AIDS [Internet] 2014 Jul;28(Suppl 3):S277–85. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000330. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24991901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matthews LT, Crankshaw T, Giddy J, Kaida A, Psaros C, Ware NC, et al. Reproductive Counseling by Clinic Healthcare Workers in Durban, South Africa: Perspectives from HIV-Infected Men and Women Reporting Serodiscordant Partners. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/146348. Article ID 146348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matthews LT, Bangsberg DR, Kaida A, Milford C, Greener R, Mosery F, et al. Reproductive counseling by clinic healthcare workers in Durban, South Africa: perspectives from HIV-positive men and women reporting serodiscordant partners, Abstract #895 (oral t.. The 20th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI 2013); Atlanta. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crankshaw TL, Matthew L, Giddy J, Kaida A, Ware NC, Smit JA, et al. A conceptual framework for understanding HIV risk behavior in the context of suporting fertility goals among HIV-serodiscordant couples. Reprod Health Matters. 2013;20(12):50–60. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(12)39639-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.National Department of Health . The 2011 National Antenatal Sentinel HIV & Syphilis Prevalence Survey In South Africa. National Department of Health; Pretoria: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pulerwitz J, Gortmaker SL, DeJong W. Measuring sexual relationship power in HIV/STD research. Sex Roles. 2000;42(7/8):637–620. [Google Scholar]

- 45.CDC . Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System [Internet] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2013. [2014 Mar 25]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/prams/ [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ahluwalia IB, Johnson C, Rogers M, Melvin C. Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS): unintended pregnancy among women having a live birth. J Womens Heal Gend Based Med. 1999;8(5):587–9. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1.1999.8.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vu L, Andrinopoulos K, Mathews C, Chopra M, Kendall C, Eisele TP. Disclosure of HIV status to sex partners among HIV-infected men and women in Cape Town, South Africa. [2014 Mar 25];AIDS Behav [Internet] 2012 Jan;16(1):132–8. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9873-y. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21197600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Crankshaw TL, Voce A, King RL, Giddy J, Sheon NM, Butler LM. Double disclosure bind: complexities of communicating an HIV diagnosis in the context of unintended pregnancy in Durban, South Africa. [2014 Mar 26];AIDS Behav [Internet] 2014 Jan;18(Suppl 1):S53–9. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0521-1. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23722975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Matthews LT, Bangsberg DR, Kaida A, Milford C, Greener R, Mosery FN, et al. South African women with recent pregnancy rarely know partner’s HIV status: implications for interventions targeting HIV serodiscordant couples, Abstract #888.. 20th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI 2013); Atlanta. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Matthews LT, Mukherjee JS. Strategies for harm reduction among HIV-affected couples who want to conceive. [2014 Mar 25];AIDS Behav [Internet] 2009 Jun;13(Suppl 1):5–11. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9551-0. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19347575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bearnot B, Werner L, Kharsany A, Abdool Karim S, Frohlich J, Abdool Karim Q. Impact of antiretroviral therapy on HIV-positive status disclosure in rural South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2012;15(3):83–4. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Simbayi LC, Kalichman SC, Strebel A, Cloete A, Henda N, Mqeketo A. Disclosure of HIV status to sex partners and sexual risk behaviours among HIV-positive men and women, Cape Town, South Africa. [2014 Mar 25];Sex Transm Infect [Internet] 2007 Feb;83(1):29–34. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.019893. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2598581&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Skogmar S, Shakely D, Lans M, Danell J, Andersson R, Tshandu N, et al. Effect of antiretroviral treatment and counselling on disclosure of HIV-serostatus in Johannesburg, South Africa. [2014 Mar 25];AIDS Care [Internet] 2006 Oct;18(7):725–30. doi: 10.1080/09540120500307248. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16971281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mlambo M, Peltzer K. HIV Sero-status Disclosure and Sexual Behaviour among HIV Positive Patients who are on Antiretroviral Treatment (ART) in Mpumalanga, South Africa. J Hum Ecol. 2011;35(1):29–41. [Google Scholar]

- 55.De Bruyn G, Bandezi N, Dladla S, Gray G. HIV-Discordant Couples: An Emerging Issue in Prevention and Treatment. South African J HIV Med. 2006;126(June):25–8. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Makin JD, Forsyth BWC, Visser MJ, Sikkema KJ, Neufeld S, Jeffery B. Factors affecting disclosure in South African HIV-positive pregnant women. [2014 Mar 25];AIDS Patient Care STDS [Internet] 2008 Nov;22(11):907–16. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0194. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2929151&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Osinde MO, Kakaire O, Kaye DK. Factors associated with disclosure of HIV serostatus to sexual partners of patients receiving HIV care in Kabale, Uganda.. Int J Gynaecol Obstet [Internet]; International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; 2012 Jul; [2014 Mar 25]. pp. 61–4. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22507263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Medley A, Garcia-Moreno C, McGill S, Maman S. Rates, barriers and outcomes of HIV serostatus disclosure among women in developing countries: implications for prevention of mother-to-child transmission programmes. [2015 Feb 13];Bull World Health Organ [Internet] 2004 Apr;82(4):299–307. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2585956&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hatcher AM, Woollett N, Pallitto CC, Mokoatle K, Stöckl H, MacPhail C, et al. Bidirectional links between HIV and intimate partner violence in pregnancy: implications for prevention of mother-to-child transmission. [2015 Feb 13];J Int AIDS Soc [Internet] 2014 Jan;17:19233. doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.1.19233. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=4220001&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Maman S, van Rooyen H, Groves AK. HIV status disclosure to families for social support in South Africa (NIMH Project Accept/HPTN 043). [2015 Jan 20];AIDS Care [Internet] 2014 Feb;26(2):226–32. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.819400. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=4074900&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dageid W, Govender K, Gordon SF. Masculinity and HIV disclosure among heterosexual South African men: implications for HIV/AIDS intervention. [2014 Mar 25];Cult Health Sex [Internet] 2012 Jan;14(8):925–40. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2012.710337. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22943462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Crankshaw TL, Mindry D, Munthree C, Letsoalo T, Maharaj P. Challenges with couples, serodiscordance and HIV disclosure: healthcare provider perspectives on delivering safer conception services for HIV-affected couples, South Africa. [2014 Mar 26];J Int AIDS Soc [Internet] 2014 Jan 3;17(1):18832. doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.1.18832. Available from: http://www.jiasociety.org/index.php/jias/article/view/18832/3543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Makhunga-Ramfolo N, Chidarikire T, Farirai T, Matji R. Provider-initiated counselling and testing (PICT): An overview. [2014 Mar 26];South Afr J HIV Med [Internet] 2011 May 26;12(2):6–11. Available from: http://www.sajhivmed.org.za/index.php/sajhivmed/article/view/651/633. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Roura M, Watson-Jones D, Kahawita TM, Ferguson L, Ross DA. Provider-initiated testing and counselling programmes in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review of their operational implementation. [2014 Mar 26];AIDS [Internet] 2013 Feb 20;27(4):617–26. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835b7048. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23364442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Desgrées-du-Loû A, Orne-Gliemann J. Couple-centred testing and counselling for HIV serodiscordant heterosexual couples in sub-Saharan Africa. Reprod Health Matters [Internet] 2008 Nov;16(32):151–61. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(08)32407-0. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19027631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jones DL, Peltzer K, Villar-Loubet O, Shikwane E, Cook R, Vamos S, et al. Reducing the risk of HIV infection during pregnancy among South African women: a randomized controlled trial. [2014 Mar 25];AIDS Care [Internet] 2013 Jan;25(6):702–9. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.772280. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23438041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wall KM, Kilembe W, Nizam A, Vwalika C, Kautzman M, Chomba E, et al. Promotion of couples’ voluntary HIV counselling and testing in Lusaka, Zambia by influence network leaders and agents. [2014 Mar 25];BMJ Open [Internet] 2012 Jan;2(5):1–11. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001171. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3467632&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kelley AL, Karita E, Sullivan PS, Katangulia F, Chomba E, Carael M, et al. Knowledge and perceptions of couples’ voluntary counseling and testing in urban Rwanda and Zambia: a cross-sectional household survey. [2014 Mar 25];PLoS One [Internet] 2011 Jan;6(5):e19573. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019573. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3090401&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Becker S, Mlay R, Schwandt HM, Lyamuya E. Comparing couples’ and individual voluntary counseling and testing for HIV at antenatal clinics in Tanzania: a randomized trial. [2014 Mar 25];AIDS Behav [Internet] 2010 Jun;14(3):558–66. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9607-1. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19763813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Orne-Gliemann J, Tchendjou PT, Miric M, Gadgil M, Butsashvili M, Eboko F, et al. Couple-oriented prenatal HIV counseling for HIV primary prevention: an acceptability study. BMC Public Health [Internet] 2010 Jan;10:197. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-197. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2873579&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Grabbe KL, Bunnell R. Reframing HIV prevention in sub-Saharan Africa using couple-centered approaches. JAMA [Internet] 2010 Jul 21;304(3):346–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1011. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20639571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.National Department of Health . South Africa Demographic and Health Survey. National Department of Health; Pretoria: 2003. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Schwartz SR, Rees H, Mehta S, Venter WDF, Taha TE, Black V. Kranzer K, editor. High incidence of unplanned pregnancy after antiretroviral therapy initiation: findings from a prospective cohort study in South Africa. [2014 Mar 26];PLoS One [Internet]. Public Library of Science. 2012 Jan;7(4):e36039. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036039. Available from: http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0036039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 74.Credé S, Hoke T, Constant D, Green MS, Moodley J, Harries J. BMC Public Health [Internet] 1. Vol. 12. BioMed Central Ltd; Jan, 2012. [2014 May 2]. Factors impacting knowledge and use of long acting and permanent contraceptive methods by postpartum HIV positive and negative women in Cape Town, South Africa: a cross-sectional study. p. 197. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3328250&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Myer L, Morroni C, Cooper D. Community attitudes towards sexual activity and childbearing by HIV-positive people in South Africa. [2014 Mar 26];AIDS Care [Internet] 2006 Oct;18(7):772–6. doi: 10.1080/09540120500409283. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16971287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lurie M, Pronyk P, de Moor E, Heyer A, de Bruyn G, Struthers H, et al. Sexual behavior and reproductive health among HIV-infected patients in urban and rural South Africa. [2014 May 16];J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr [Internet] 2008 Apr 1;47(4):484–93. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181648de8. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3811008&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Smit JA, Church K, Milford C, Harrison AD, Beksinska ME. Key informant perspectives on policy- and service-level challenges and opportunities for delivering integrated sexual and reproductive health and HIV care in South Africa. [2014 Mar 25];PLoS One [Internet] 2012 Jan;12(1):48. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-48. Available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/12/48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.De Bruyn M. Living with HIV: challenges in reproductive health care in South Africa. Afr J Reprod Health [Internet] 2004 Apr;8(1):92–8. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15487620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Peltzer K, Chao L-W, Dana P. Family planning among HIV positive and negative prevention of mother to child transmission (PMTCT) clients in a resource poor setting in South Africa. [2014 Apr 30];AIDS Behav [Internet] 2009 Oct;13(5):973–9. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9365-5. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18286365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.WHO Department of Reproductive Health and Research Programming for male involvement in reproductive health: Report of the meeting of WHO Regional Advisers in Reproductive Health WHO/PAHO; Washington, DC, USA. 5–7 September. 2001; Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 81.The Global Network of People Living with HIV/AIDS . Advancing the sexual and reproductive health and human rights of people living with HIV. The Global Network of People Living with HIV/AIDS; Amsterdam: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Boonstra H. Brief. Guttmacher Institute; 2004. [2014 May 15]. Meeting the Sexual and Reproductive Health Needs of People Living with HIV [Internet]. Available from: http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/IB_HIV.html. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Villar-Loubet OM, Cook R, Chakhtoura N, Peltzer K, Weiss SM, Shikwane ME, et al. HIV knowledge and sexual risk behavior among pregnant couples in South Africa: the PartnerPlus project. [2014 Mar 25];AIDS Behav [Internet] 2013 Feb;17(2):479–87. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0360-5. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23161209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mlay R, Lugina H, Becker S. Couple counselling and testing for HIV at antenatal clinics: views from men, women and counsellors. [2014 Mar 25];AIDS Care [Internet] 2008 Mar;20(3):356–60. doi: 10.1080/09540120701561304. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18351484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pettifor A, MacPhail C, Suchindran S, Delany-Moretlwe S. Factors associated with HIV testing among public sector clinic attendees in Johannesburg, South Africa. [2014 Mar 25];AIDS Behav [Internet] 2010 Aug;14(4):913–21. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9462-5. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18931903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rosenberg NE, Pettifor AE, De Bruyn G, Westreich D, Delany-Moretlwe S, Behets F, et al. HIV testing and counseling leads to immediate consistent condom use among South African stable HIV-discordant couples. [2014 Mar 26];J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr [Internet] 2013 Feb 1;62(2):226–33. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31827971ca. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3548982&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Maughan-Brown B, Venkataramani AS. Learning that circumcision is protective against HIV: risk compensation among men and women in Cape Town, South Africa. [2015 Feb 13];PLoS One [Internet] 2012 Jan 19;7(7):e40753. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040753. Available from: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0040753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Layer EH, Beckham SW, Mgeni L, Shembilu C, Momburi RB, Kennedy CE. “After my husband’s circumcision, I know that I am safe from diseases”: women's attitudes and risk perceptions towards male circumcision in Iringa, Tanzania. [2015 Feb 13];PLoS One [Internet] 2013 Jan;8(8):e74391. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074391. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3756960&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mantell JE, Smit JA, Saffitz JL, Milford C, Mosery N, Mabude Z, et al. Medical male circumcision and HIV risk: perceptions of women in a higher learning institution in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. [2015 Feb 13];Sex Health [Internet] 2013 May;10(2):112–8. doi: 10.1071/SH12067. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3963517&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Harries J, Cooper D, Myer L, Bracken H, Zweigenthal V, Orner P. Policy maker and health care provider perspectives on reproductive decision-making amongst HIV-infected individuals in South Africa. [2014 Mar 26];BMC Public Health [Internet] 2007 Jan;7:282. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-282. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2098761&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Matthews L, Milford C, Greener R, Psaros C, Safren S, Harrison A, et al. Barriers and Facilitators to Provider-initiated Assessment of Fertility Intentions among Men and Women Living with HIV in South Africa.. 17th ICASA (International Conference on AIDS and STIs in Africa); Cape Town. 7-11 December; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Matthews LT, Baeten JM, Celum C, Bangsberg DR. Periconception pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV transmission: benefits, risks, and challenges to implementation. [2014 Mar 25];AIDS [Internet] 2010 Aug 24;24(13):1975–82. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833bedeb. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3773599&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chadwick RJ, Mantell JE, Moodley J, Harries J, Zweigenthal V, Cooper D. Safer conception interventions for HIV-affected couples: implications for resource-constrained settings. [2015 Feb 13];Top Antivir Med [Internet] 2011 Nov;19(4):148–55. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22156217. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mindry D, Maman S, Chirowodza A, Muravha T, van Rooyen H, Coates T. Looking to the future: South African men and women negotiating HIV risk and relationship intimacy. [2014 Mar 26];Cult Health Sex [Internet] 2011 May;13(5):589–602. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2011.560965. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3071520&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wagner GJ, Goggin K, Mindry D, Beyeza-Kashesya J, Finocchario-Kessler S, Woldetsadik MA, et al. Correlates of Use of Timed Unprotected Intercourse to Reduce Horizontal Transmission Among Ugandan HIV Clients with Fertility Intentions. [2015 Feb 13];AIDS Behav [Internet] 2014 Oct 4; doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0906-9. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25280448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 96.Liao C, Wahab M, Anderson J, Coleman JS. Reclaiming fertility awareness methods to inform timed intercourse for HIV serodiscordant couples attempting to conceive. [2015 Jan 26];J Int AIDS Soc [Internet] 2015 Jan;18(1):19447. doi: 10.7448/IAS.18.1.19447. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=4289674&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mmeje O, van der Poel S, Workneh M, Njoroge B, Bukusi E, Cohen CR. Achieving pregnancy safely: perspectives on timed vaginal insemination among HIV-serodiscordant couples and health-care providers in Kisumu, Kenya. [2015 Feb 13];AIDS Care [Internet] 2015 Jan;27(1):10–6. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2014.946385. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25105422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Matthews LT, Moore L, Crankshaw TL, Milford C, Mosery FN, Greener R, et al. South Africans with recent pregnancy rarely know partner’s HIV serostatus: implications for serodiscordant couples interventions. [2015 Feb 13];BMC Public Health [Internet] 2014 Jan;14(1):843. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-843. Available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/14/843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kaida A, Laher F, Strathdee SA, Money D, Janssen PA, Hogg RS, et al. Contraceptive use and method preference among women in Soweto, South Africa: the influence of expanding access to HIV care and treatment services. [2014 May 4];PLoS One [Internet] 2010 Jan;5(11):e13868. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013868. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2974641&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Myer L, Rebe K, Morroni C. Missed opportunities to address reproductive health care needs among HIV-infected women in antiretroviral therapy programmes. [2014 May 16];Trop Med Int Health [Internet] 2007 Dec;12(12):1484–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01955.x. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18076556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.