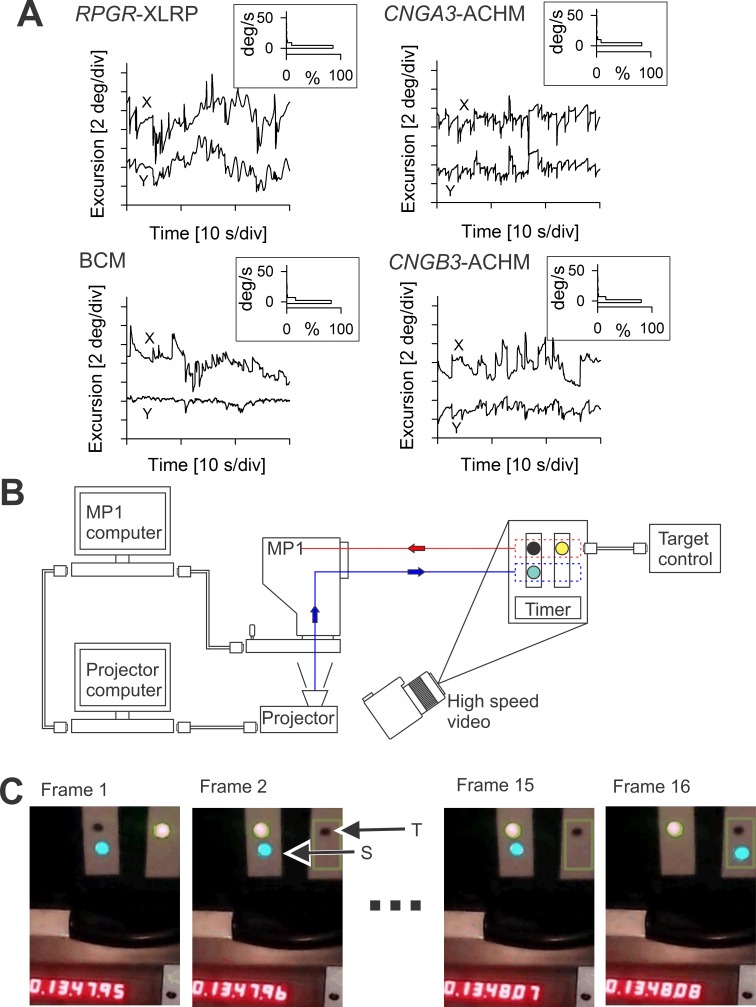

Figure 3.

Expected eye movements and retinal tracking performance. (A) Eye movements of a 66-year-old RPGR-XLRP patient with end-stage retinal degeneration and light-perception visual acuity (upper left), a 26-year-old BCM patient with 20/100 visual acuity (lower left), a 13-year-old CNGA3-ACHM patient with 20/125 acuity (upper right), and an 18-year-old CNGB3-ACHM patient with 20/150 acuity (lower right). For each subject, eye movement data are shown as a chart recording for x and y directions (main images). During the recording, the XLRP patient was trying to hold the direction of his gaze without any visual cues in a dark room; the remaining patients, on the other hand, had a ∼1° diameter visible fixation target. The velocity of the eye movements was calculated and is shown as histograms (insets). (B) Schematic of the modified MP1 with its standard connection to the MP1 computer, which in turn is connected to an external projector computer that drives the projector coupled optically into the light path of the MP1. Also shown is the experimental system of a target, stimulus, and timer setup to measure the maximum time delay involved between tracking the target and displaying a stimulus at the correct spatial location. In this experimental system, a high-speed camera images the temporal sequence of the alternating target and the resulting stimulus movements. (C) First two and last two video frames from a representative sequence of 16 frames showing simultaneously the target (T) being tracked, the stimulus (S) that is driven by the modified MP1, and the 1/100-second timer. The video frames represent 1/120 second.