Abstract

OBJECTIVE

In the field of global mental health, there is a need for identifying core values and competencies to guide training programs in professional practice as well as in academia. This paper presents the results of interdisciplinary discussions fostered during an annual meeting of the Society for the Study of Psychiatry and Culture to develop recommendations for value-driven innovation in global mental health training.

METHODS

Participants (n=48), who registered for a dedicated workshop on global mental health training advertised in conference proceedings, included both established faculty and current students engaged in learning, practice, and research. They proffered recommendations in five areas of training curriculum: values, competencies, training experiences, resources, and evaluation.

RESULTS

Priority values included humility, ethical awareness of power differentials, collaborative action, and “deep accountability” when working in low-resource settings in both low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) and high-income countries. Competencies included flexibility and tolerating ambiguity when working across diverse settings, the ability to systematically evaluate personal biases, historical and linguistic proficiency, and evaluation skills across a range of stakeholders. Training experiences included didactics, language, self-awareness, and supervision in immersive activities related to professional or academic work. Resources included connections with diverse faculty such as social scientists and mentors other than medical practitioners, institutional commitment through protected time and funding, and sustainable collaborations with partners in low resource settings. Finally, evaluation skills built upon community-based participatory methods, 360-degree feedback from partners in low-resource settings, and observed structured clinical evaluations (OSCEs) with people of different cultural backgrounds.

CONCLUSIONS

Global mental health training, as envisioned in this workshop, exemplifies an ethos of working through power differentials across clinical, professional, and social contexts in order to form longstanding collaborations. If incorporated into the ACGME/ABPN Psychiatry Milestone Project, such recommendations will improve training gained through international experiences as well as the everyday training of mental health professionals, global health practitioners, and social scientists.

Keywords: Curriculum development, Cross-cultural psychiatry, Global mental health, Medical education, Training innovation

Building upon the consensus definition of global health (1), global mental health is “an area for study, research and practice that places a priority on improving health and achieving equity in health for all people worldwide,” (2, p.xi). The focus in global mental health (GMH) is thus on achieving equity in the distribution of resources for mental health systems, as well as equity in mental health outcomes (2). The field of GMH is fast-expanding, with increasing attention drawn to the core values that must guide training programs established for professional practice and academic research, both in high and low income countries (3–6). Within GMH, efforts to establish core competencies seek to achieve these dual goals of competence and equity, specifically to benefit partnerships in low-resources settings in both low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) and high-income countries (HIC) (7). However, core values and required competencies have not been well articulated for GMH training programs in HIC. It is clear, for example, that the field needs to make explicit the value of placing trainees from HIC into LMIC, beyond the benefit of gaining short-term international experience. There are many uncertainties and dissonance of expectations that can arise from short-term medical missions (8). Clearly articulating goals, values, and competencies are essential for GMH training more broadly, within academia and clinical practice. Indeed, reflection on core values is critical to the fields of global health, the social sciences, and medical practice, if we are to hold fast to our stated mandate of care (9, 10).

To address this gap, we convened a formal discussion of such issues to help identify key values, required competencies, training experiences, resources, and evaluation approaches for GMH training for medical/graduate students, trainees in psychiatry residency, fellows and post-doctoral students, social scientists, and collaborators from LMIC. Although GMH as a field seeks to address inequities broadly across settings, our focus was on the competencies relevant for trainees from HIC for working in low-resource settings.

METHODS

We took advantage of a specific venue, the 2015 annual meeting of the Society for the Study of Psychiatry and Culture (SSPC), to convene a workshop dedicated to GMH training. The theme of the Society’s meeting was “Culture and Global Mental Health.” Established in 1979, SSPC (www.psychiatryandculture.org) is a nonprofit, interdisciplinary organization devoted to promoting cultural psychiatry through international efforts to enhance education, clinical practice, policy, and research. The three-day conference (April 23–25, 2015, Providence, Rhode Island) convened 160 participants, of which 48 participated in the workshop dedicated to GMH training. The two-hour workshop was held on April 24th from 1:00–3:15PM as one of three workshops dedicated to focused discussion on specific themes, and entailed no participation fee above that levied for conference registration.

Participants were invited to pre-register to the workshop – those who pre-registered were invited to provide input on what they perceived to be the most important values and competencies for GMH training, through an online free-listing exercise: “Please provide a list of five values that you think should guide the mission of global mental health,” and “Please provide a list of five competencies that you think are important for working in the field of global mental health.” This pre-conference assignment was adapted from the first step of standard Delphi priority-setting activities (11).

Forty-eight people participated in the workshop. The majority were established academics in the field of psychiatry (22 faculty, five residents, four fellows), social sciences (six faculty in anthropology and one in sociology), and public health (one faculty), in addition to eight students (in medicine, global health, psychology, and anthropology). There were three practitioners (family physician, public health, and human rights lawyer), and eight participants involved as GMH program coordinators (some individuals had joint appointments or were in dual degree training programs). Eleven (23%) participants were from LMIC, including China, India, Nepal, Guatemala, Mexico, and Venezuela. All participants had first-hand GMH experiences, which included education and training, clinical service, and research throughout all World Health Organization regional clusters, e.g., Central America and the Caribbean, South America, Eastern Europe, Southern and Eastern Asia, and Pacific Islands. Their training work in LMIC ranged from brief clinical programs (e.g., training medical students or primary care workers for 1–2 weeks) to long-term capacity building programs (e.g., multiyear training, apprenticeship, and supervision programs). Their LMIC research involved a broad set of methods (epidemiology, services research, biological psychiatry, and ethnography and other social science approaches), with the majority of projects conducted in multidisciplinary teams. Most participants described experiences working in low-resource settings in HIC, as well. All GMH program facilitators had extensive experience in collaborative approaches to training and program implementation.

At the workshop, we employed established techniques for focus group discussion to establish priorities in health education and practice (12). Participants were invited to complete group work to produce recommendations in five areas, to identify the following items:

three values central to GMH training (from the free-listing exercise),

three competencies needed to achieve these values (from the free-listing exercise),

training and experiences needed to achieve such competencies,

resources needed to provide such training opportunities, and

evaluation techniques to demonstrate competence in GMH, post-training.

These recommendations were developed with the aim of providing insights for innovation on important aspects of GMH activity, in order to benefit five main stakeholder groups: namely, 1) medical/graduate students, 2) trainees in psychiatry residency, 3) fellows and post-doctoral students, 4) social scientists, and 5) collaborators from low-resource settings.

Workshop participants self-selected into discussion groups for these five categories, joining five different round tables set up in separate spaces of the conference room. They could choose to join any of the five stakeholder groups, regardless of their own interests or stages of training. Formation of heterogeneous groups was encouraged: we used mixed groups to foster discussions about successful or challenging aspects of current inter-disciplinary programs and training, given that groups with participants at different career stages could reflect together on what aspects of training were most helpful given current activities.

Each round table was provided with the list of values and competencies generated by the online free-listing exercise. Participants were then instructed to identify, through back-and-forth discussion at their given tables, the three most important core values and competencies from the existing list, or to generate their own alternatives. They were also asked, in three consecutive blocks of time, to identify their most important recommendations for training experiences, resource needs, and evaluation techniques.

After discussion, each round table took the stage to share their main recommendations to workshop participants at large, crystalizing them into short concluding statements. The five group presentations, and the discussion that followed, were audio recorded for transcription. Participants were informed that the purpose of this exercise was to disseminate their recommendations in academic venues.

RESULTS

The online free-listing exercise yielded a list of 31 core values and 28 required competencies for GMH training. These lists were provided to the five groups, in order to seed discussions and achieve consensus on identifying the most important items. We summarize the recommendations of participants below. The supplementary material available online includes a breakdown of items by domain for each group.

Values

In the online free-listing exercise, values related to equality and equity (e.g., social inclusion, access to care, gender equality) constituted 19% of responses. Sustainable partnerships and collaboration, including support of both human capital and infrastructure, constituted 16% of responses. Cultural and linguistic competence, including knowledge of idioms of distress, constituted 13% of responses. Other responses included humility (10%), justice and human rights (10%), differentiating distress versus disorder (6%), do no harm (6%), and respect (6%).

Building upon these lists, workshop groups prioritized humility, respect, and ethics in the context of collaborations. The quotes provided below and in subsequent sections represent consensus statements from workshop groups.

“Our salient values are humility and respect for others, partnerships that value working with a diverse group, and… being compassionate.”

“For values, we discussed having long-term collaborative ethical and sustainable partnerships, being open-minded and respectful of other cultures and patient experiences and suffering, and humility.”

“… mutually-beneficial collaboration, humility, open-mindedness, respect, partnership, infrastructure, capacity building, and knowledge for sustained training [are important values].”

“We developed an acronym for the core values – PAR – namely, Partnership, Accountability, and Reflexivity. When we say accountability, that is not merely tracking the money flowing into a program, but rather an accountability to people, what is known as deep accountability to a people-centered agenda. By reflexivity, we mean that you are constantly holding a critical eye to the performance of what you are doing.”

“Our first value is to form collaborative, mutually beneficial relationships with partners abroad, our second was respect and understanding of local mental health treatment approaches, and lastly conducting long term ethical and sustainable work.”

Competencies

The largest category of competency free-list responses (21%) referred to cross-cultural communication including knowledge of idioms of distress and other culturally-appropriate ways to discuss mental health in a non-stigmatizing manner. Other competency categories included the ability to collaborate in interdisciplinary teams (14%); conducting self-evaluations of clinical, research, and community engagement practices (11%); aptitude in family and couples therapy (11%); conducting cultural formulation interviews and eliciting explanatory models (11%); knowledge of WHO essential medications and government free drug lists in respective countries (4%); evidence-based teaching and training strategies (4%); culturally adapting treatment manuals (4%); evidence-based approaches to advocacy (4%); and other competencies (20%).

Workshop groups emphasized a range of competencies from listening skills to knowledge of political context to critical thinking skills:

“The primary competency that we would like to gain is a non-judgmental approach, which includes tolerance.”

“Competencies within this ideal partnership include understanding systems and how they operate, ways to foster collaboration, and how to evaluate that relationship. Within an open-minded, non-judgmental stance are competencies for good listening skills, flexibility, tolerating ambiguity and differences, and being open to new experiences. Competencies under humility include self-awareness and recognition of power differentials, resource differences, cultural biases, and systems differences.”

“[The main competencies were] flexibility, [sensitivity to] bias, humility and being able to treat mental disorders in a manner appropriate for the cultural context. A second group of competencies is knowing the cultural and political context of the situation where you are providing care.”

“Our competencies are interdisciplinarity, critical thinking skills or deep knowledge of context, and ethical engagement. In other words, we want to draw attention to our accountability to people rather than to the program.”

“Competencies that we chose were, first, awareness of biased assumptions, and, second, knowledge, skills, and attitudes specifically regarding systems, operational management, and team based approaches. When we expanded on the competencies, we wanted to think about modeling self- evaluations, and the awareness that we all have biases and allow our own biases to be shared, and [demonstrate] how sharing can normalize these biases. We wanted this to be in group settings in LMIC settings.”

Training

Training included (a) class didactics with a focus on ethics, history, and critical social theory; (b) experiences fostering self-reflection and awareness; (c) immersive field experiences; and (b) health systems practice and theory:

“Training would include classes in ethical considerations of science grounded in history, self-awareness and reflection.”

“Training should be incorporated into basic psychiatry training and offer additional in depth opportunities for those with specific interest. Prior to international experiences, training should include case presentations with analysis accompanied by didactics and locally relevant preparation and experiences. Training should be longitudinal and include experiential training as well as mentorship. Many of these elements are in psychiatry training; the added value includes how the training experiences are framed and expanding existing components to address their global applicability. We recommend optimizing components of existing training for all residents versus relegating these elements to only a dedicated elective for a subset of trainees. For example, in general residency, one should consider non-familiar populations that residents are not currently encountering and practicing the competencies of a non-judgmental stance, humility, self-awareness, and sensitivity to power differentials. Methods to accomplish this include role-plays, 360-degree evaluations, some coursework and didactics on the history of both GMH and the regions of the populations referenced.”

“For training, a key experience is conducting a self-cultural formulation and other systematic approaches to understanding oneself. Part of this process includes job training and doing preparatory work before you go for an international experience.”

“For gaining actual training experience, we recommend immersive field experiences, critical social theory, and mixed research methods. Note that immersive practice means to ‘be with the people’, and note that critical skills and mixed methods allow you to better communicate across disciplines, which is necessary for GMH training because we all need to engage with other perspective.”

“Regarding [training] skills: we wanted to get a broader sense of what are social determinants of what problems are occurring and eliciting what is important and incorporating that material into our content. Regarding who are the voices [that matter], [if] we [mental health specialists] are the only voices represented, [then it] is not effective. So, [we should] have global voices, including nurses, parents, policy makers, traditional healers, and other LMIC stakeholders who are going to be involved [in any implementation, practice, and research]. The last competency group was skills and attitudes for team based work. [This includes] what services are already embedded and finding out about the infrastructure, we want to bring in experts who do have knowledge about operational management and systems both in our economies and the ones we are trying to work with. We want for things to be feasible and sustainable because we don’t want to be a burden to the people we are working with.”

Resources

Resource needs incorporated funding, curriculum development, mentorship, and long-standing partnerships with local collaborators wherever training, clinical, or research activities are conducted:

“In terms of resources, we need educational leadership buy-in for curriculum development, physical space and materials [for teaching] and flexibility in tailoring programs in order to accomplish all of this. We need faculty training and buy-in and expansion from the traditional faculty to include non-medical faculty, service users, and other stakeholders. For end-user engagement involvement, it may be good to use technology… We need people with language expertise and partnerships in terms of local faculty, field site staff, and other partners. We will [also need institutional support to develop and implement] an evaluation system in terms… We have envisioned an introductory course [for medical and graduate students] plus a longitudinal didactic component. That said, we need to ensure [that training] is not only didactically but really interactive and participatory. Incorporation of technology will facilitate training evaluation and trainee buy-in… Student buy-in comes in two types: all students should be invested in gaining skills in being nonjudgmental, which would be a universal competency, and in particular, there would be students who are interested specifically in GMH, who would need advanced training.”

“In terms of resources, time and money, including salary support, are vital. You also need commitment and on the parts of trainees for continuity of their partnerships and as well on the part of faculty who are going to be providing the courses, mentorship, and training programs. Within the institution, you need inter-institutional partnerships and collaboration with social sciences and other colleagues including collaborating with non-medical partners.”

“Crucial to training experiences would be role models and mentors. In terms of resources, we would need time, [availability of personal] therapy, a flexible curriculum with time to explore and have tailored experiences, as well as having a mentor to help with the timeline and local partnerships.”

“Our first-priority resource is diverse mentorship. Second, we need platforms of exchange, ones that facilitate a brokering of knowledge. And as a third important resource, we need innovative funding, namely funding that allows you to pursue good ideas.”

“Regarding resources: we need train the trainer models within the country context that we are working… We need relationships with institutions already locally present, and we need to have their support and positive relationships with them no matter what. We need the framework to be sustainable and dynamic… to periodically reevaluate and do assessments to see if it is working and make adjustments… [We need a] collaborative process of making goals with whomever we are working.”

Evaluation

Evaluation priorities highlighted self-evaluation including assessing impact on local communities and partners. In addition to clinical skills, assessment of language and other context factors were prioritized. Feedback from partners and beneficiaries was considered indispensable.

“Evaluations should measure attitude and skills, such as using observations to look at one’s attitudes and using a 360 [degree feedback; 360 degree feedback refers to a form of multi-rater feedback comprising supervisors, direct reports, peers, and self evaluation]. Knowledge pre- and post-tests would be another way to evaluate training gains… Another way to evaluate is through language testing because a GMH training program should include language skills. Patient satisfaction [tools] would be one way to see if someone is being compassionate… There should also be participation indicators to see to what extent people are involved in the community. Self-reflection should be included as a personalized component. There should also be project component with specific logs, and, if applicable, a thesis. [We should also document] presentations and publications.”

“For evaluations, there is the individual level, the program level, and the collaborations abroad. We prioritize how to evaluate yourself as a way of maximizing your effectiveness and contribution to GMH, including assessing longevity and functioning as basic factors. Prior to going abroad, one can practice with an evaluation simulation considering the competencies discussed above as influenced by the core values. Evaluation of both the trainees in the program and the work they are doing abroad is critical. To evaluate your impact, one can track the scholarly projects being done.”

“In terms of evaluations, it is key to obtain evaluations from those who will be potentially benefitting [from the services]. Surveys could be used to evaluate the quality of [collaborative and clinical] relationships and how time was spent in electives.”

“Finally, in terms of evaluation, we want three things. One is iterative process reports that focus on the ‘how’ and ‘what’ you are doing, namely, reports that evaluate the GMH training process and not just training outcomes: we would like to know how you are doing not just what you are doing in training programs. Second, we want a focus on systematic community feedback on training programs because you need people’s input and buy-in all along the way. And finally, we need a critical knowledge dissemination to be able to learn from the past and foster innovation and good practice.”

“For evaluation metrics, we should incorporate existing metrics; some are web-based. We want to measure who we are reaching, and have things changed as a result of our involvement. How effective is our work and what are the outcomes? We want to do self-evaluation and see how effective we are in providing services that we think we are providing, and how effective are we in comparison to who is already doing the work. We also wanted to integrate the consequences of our participation, we do not want burden others with consequences on our participation. This integrates social determinants in the context. We also want to incorporate what are their targets and objectives and what social inequalities affect their impact. This can be done through a case presentation to find out who are the people involved and what are the skills of the people involved in the programming.”

DISCUSSION

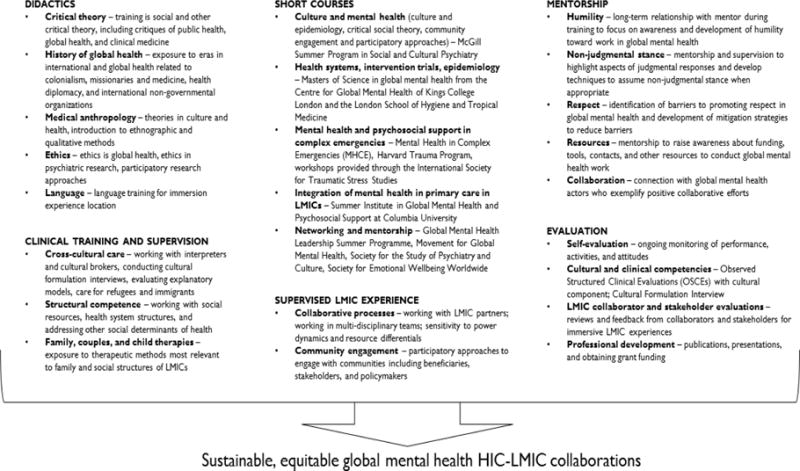

Participants were tasked with developing recommendations for GMH values and competencies, as well as defining the training experiences, resources, and evaluation techniques that can help achieve these goals. Our findings are a useful starting point for improving GMH training, especially where scholars and professionals from HIC work in collaborations in LMIC institutions and in low-resource settings in HIC. Figure 1 provides an overview of key elements in a value-driven GMH training program, including specific resources from existing short courses.

Figure 1.

Components for value-driven global mental health training

The group consensus about values central to GMH training focused on humility, attention to ethics, and the development of collaborative partnerships. “Deep accountability” to patients and their families was emphasized in order to focus attention on a people-centered agenda (9, 15), as well as accountability to clinical and research collaborators in LMIC and other low-resource settings in response to the historical global health efforts where priorities were defined by individuals and institutions in imposing a colonialist vision of human rights without local input or understanding the local context (13). Recent examples in global health and GMH demonstrate a commitment to “deep accountability” and collaborative partnerships (6, 9, 14, 15). Multiple competencies were highlighted to achieve these values, among them, flexibility; ability to tolerate ambiguity and to evaluate one’s personal biases; understand critical theory in social science; historical and linguistic knowledge related to clinical populations and community settings; and skills required to evaluate impact across a range of stakeholders, from patients to clinical collaborators to policy makers. Many of these elements have been highlighted by the recent call to shift away from cultural competency to structural competency in training medical professionals (16). The group proposed various training experiences to achieve these competencies, including didactics in global health, medical anthropology, critical theory, philosophy, and ethics; language training; training in self-awareness and structured reflection; supervised local experiences across cultural groups; and supervised immersive field experiences in settings with low resources. More guidelines should be produced for collaborative engagement, such as recent recommendations for collaborative academic writing for LMIC-HIC research partnerships (17).

Consensus about resources was unanimous about the need to have broad base multidisciplinary faculty/mentorship including social scientists and other non-medical mentors (18), institutional commitment through protected time and funding for GMH faculty (19), and sustainable collaborative partnerships between practitioners and researchers working in high- and low-resource settings. The resource challenges are global, although exponentially worse in LMIC. Few HIC institutions offer the described resources to trainees in GMH. Those in LMIC and other low-resource settings are often burdened by a range of clinical, research, and administrative duties due to the lack of mental health specialists in most these settings, and many have little or no access to training and supervision. Free access to online courses and investment in information technology was proposed as a first step to enhance learning opportunities for LMIC collaborators.

The group was also unanimous on the need to evaluate trainings to demonstrate competence in GMH, and several possible modalities were discussed. Evaluations are required for all different levels of training (e.g., trainee/student, faculty/mentor), as well as for the multiple stakeholders involved in the research (e.g., community, patient, relative, provider, administrator, policy maker, researcher, etc.). Ultimately, by developing a range of competency evaluation approaches, GMH training programs will be better positioned to judge preparation and the degree of supervision needed for GMH experiences.

From introspection to deep accountability, the need to address power differentials through active collaborative partnerships was widely discussed (14). Critical Medical Anthropology explores power differentials within socioeconomic systems, medical systems, and patient-provider interactions (20). Collaborative models such as Community Based Participatory Research (CBPR) (14) can provide both a training and a research framework to provide feedback to research teams; facilitate communication between researchers and communities; and challenge assumptions about needs, barriers, facilitators, conflicts and potential approaches. Further, adaptability, flexibility and managing uncertainties are skills attained through frameworks like CBPR.

GMH training can build upon the use of observed structured clinical evaluations (OSCE) in clinical training. A cultural OSCE has been developed to evaluate working with diverse populations (21). A GMH therapist common factors tool has also been developed for evaluation of both trainees and GMH practitioners, and it can be incorporated into evaluation of non-specialist health workers in diverse cultural settings (22). New materials exist for training in the cultural formulation interview (23).

Psychiatric residency training Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) competencies (5) or the goals of The Psychiatry Milestone Project by the ACGME and The American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology (APBN) (24) closely align with the GMH competencies defined by the workgroup. Psychiatry Milestone Project categories relevant to GMH include Professionalism (PROF), Psychiatric Care (PC), Interpersonal and Communication Skills (ICS), Medical Knowledge (MK), and Systems Based Practice (SBP). Competencies contributing to humility, respect, and compassion when working across cultural groups are reflected in Milestone PROF1, “Compassion, integrity, respect for others, sensitivity to diverse patient populations, adherence to ethical principles.” Milestone PC4, “Psychotherapy,” is a good example of how this self-awareness is integrated into treatment planning, e.g., “Personalizes treatment based on self-awareness.” The concept of deep accountability fits with the Milestone PROF2, “Accountability to self, patients, colleagues, and the profession.” Promoting long-term GMH collaboration is also an extension of Milestone ICS1, “Relationship development and conflict management with patients, families, colleagues, and members of the health care team.” Other GMH competencies are reflected in MK1, “Development across the lifespan” through an item on “cultural and economic influences on personality development”; and in MK2, “Psychopathology,” which emphasizes competency “in diverse patient populations.” And finally, Milestones SBP3, “Community-based care” which includes designing systems and using community groups and advocacy groups, and Milestone SBP4, “Consultation to non-psychiatric medical providers and non-medical systems”, are both central to effective GMH work.

Regarding limitations, this process represents views of a self-selected group of attendees of an annual conference of a single academic professional society. Their views may not represent views on the practice of psychiatry or the conduct of GMH research in the rest of the field. We used a process of heterogeneous groupings to develop priorities for different stages of training in order to foster collaborative approaches from various perspectives and career paths. If we had used homogeneous groups, e.g., limiting the post-doctoral group only to current fellows, doing so would likely have produced a different set of recommendations. Collaborative processes of developing training recommendations with other professional societies (7, 25) would be beneficial to identify priorities not captured through the limited procedures we conducted at a single academic professional society conference with time limitations. More importantly, the workshop participants emphasized the need for involvement of LMIC clinicians, research, and institutional partners to be central in identifying values and competencies within training programs. Eleven clinicians and social scientists from LMIC (23% of participants) engaged in the workshop, but most were currently based in HIC institutions. Therefore, future training priority setting activities are needed with LMIC collaborators based in LMIC institutions.

In conclusion, GMH training, as envisioned by participants in this workshop, needs to be grounded in an ethos of recognizing and working with power differentials across clinical, professional, and cultural context to form longstanding collaborations. The ability to identify, engage with, and shift power dynamics is an aspect of good social and psychotherapeutic skills: GMH presents an opportunity to apply these important skills to a broad systems level, striving for both cultural and structural competence in meeting the needs of people and their families across diverse communities. This will help achieve the objectives of GMH to decrease disparities in access to quality mental health care.

Supplementary Material

Implications for Educators.

Innovations in global mental health training rest upon promoting key values, such as humility, collaboration, and sensitivity to power differentials, for collaborative work partnerships.

Global mental health key competencies include tolerating uncertainty, systematically evaluating personal biases, and engaging with diverse stakeholders.

Global mental health training must include didactics on history, ethics, and culture; language training; and supervision in low-resource settings.

Global mental health training programs require diverse faculty including social scientists, sustainable international partnerships, and protected time and funding for trainees and faculty.

Evaluation of global mental health trainees must include cross-cultural OSCEs, feedback from international partners, and community-based outputs and outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the participants of the 2015 Society for the Study of Psychiatry and Culture annual meeting workshop on training in global mental health (April 23–25, Providence, Rhode Island, USA).

Funding: The authors acknowledge salary support for Dr. Kohrt through K01MH104310 and Dr. Tsai through K23M096620 and thank Anvita Bhardwaj for her assistance with workshop transcription.

Footnotes

Disclosure On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Brandon A. Kohrt, Duke Global Health Institute, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, USA.

Carla B. Marienfeld, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut, USA

Catherine Panter-Brick, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, USA.

Alexander C. Tsai, Center for Global Health, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA

Milton L. Wainberg, Global Mental Health Program, Columbia University/New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, NY, USA

References

- 1.Koplan JP, Bond TC, Merson MH, et al. Towards a common definition of global health. The Lancet. 2009;373:1993–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60332-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel V, Minas H, Cohen A, et al. Global Mental Health: Principles and Practice. Oxford University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsai AC, Fricchione GL, Walensky RP, et al. Global health training in US graduate psychiatric education. Acad Psychiatry. 2014;38:426–32. doi: 10.1007/s40596-014-0092-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marienfeld C, Rohrbaugh R. Impact of a Global Mental Health Program on a Residency Training Program. Acad Psychiatry. 2013:37. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.12070132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Dyke C, Tong L, Mack K. Global mental health training for United States psychiatric residents. Acad Psychiatry. 2011;35:354–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.35.6.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sweetland AC, Oquendo MA, Sidat M, et al. Closing the Mental Health Gap in Low-income Settings by Building Research Capacity: Perspectives from Mozambique. Annals of Global Health. 2014;80:126–33. doi: 10.1016/j.aogh.2014.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collins PY, Musisi S, Frehywot S, et al. The core competencies for mental, neurological, and substance use disorder care in sub-Saharan Africa. Global health action. 2015:8. doi: 10.3402/gha.v8.26682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abramowitz S, Marten M, Panter-Brick C. Medical Humanitarianism: Anthropologists Speak Out on Policy and Practice. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 2015;29:1–23. doi: 10.1111/maq.12139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Panter-Brick C, Eggerman M, Tomlinson M. How might global health master deadly sins and strive for greater virtues? Global Health Action. 2014;7 doi: 10.3402/gha.v7.23411. 10.3402/gha.v7.23411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raviola G, Becker AE, Farmer P. A global scope for global health–including mental health. Lancet. 2011;378:1613–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60941-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dalkey N, Helmer O. An experimental application of the Delphi method to the use of experts. Management science. 1963;9:458–67. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bowling A. Research Methods In Health: Investigating Health And Health Services. McGraw-Hill: Education/Open University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Butt L. The suffering stranger: Medical anthropology and international morality. Medical Anthropology. 2002;21:1–24. doi: 10.1080/01459740210619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, et al. REVIEW OF COMMUNITY-BASED RESEARCH: Assessing Partnership Approaches to Improve Public Health. Annual Review of Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gunderson GR, Cochrane JR. Religion and the health of the public: shifting the paradigm. Basingstoke, United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Metzl JM, Hansen H. Structural competency: Theorizing a new medical engagement with stigma and inequality. Social Science & Medicine. 2014;103:126–33. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kohrt BA, Upadhaya N, Luitel NP, et al. Authorship in Global Mental Health Research: Recommendations for Collaborative Approaches to Writing and Publishing. Annals of Global Health. 2014;80:134–42. doi: 10.1016/j.aogh.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Straus SE, Johnson MO, Marquez C, et al. Characteristics of Successful and Failed Mentoring Relationships: A Qualitative Study Across Two Academic Health Centers. Academic medicine: journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2013;88:82–9. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31827647a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsai AC, Ordóñez AE, Reus VI, et al. Eleven-Year Outcomes from an Integrated Residency Program to Train Research Psychiatrists. Academic medicine: journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2013;88:983–8. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318294f95d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baer HA, Singer M, Susser I. Medical Anthropology and the World System. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Padilla A. Teaching cultural competence in psychiatry utilizing an observed structured clnical examination. Providence, Rhode Island. “Culture and Global Mental Health” 36th Annual Meeting of the Society for the Study of Psychiatry and Culture; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kohrt BA, Jordans MJD, Rai S, et al. Therapist Competence in Global Mental Health: Development of the Enhancing Assessment of Common Therapeutic Factors (ENACT) Rating Scale. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2015;69:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewis-Fernandez R, Aggarwal NK, Hinton L, et al. DSM5 Handbook on the Cultural Formulation Interview. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 24.ACGME/ABPN. The Psychiatry Milestone Project: The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, and The American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tomlinson M, Rudan I, Saxena S, et al. Setting priorities for global mental health research. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2009;87:438–46. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.054353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.