Abstract

African American women are disproportionately affected by multiple sexual and reproductive health conditions compared with women of other races/ethnicities. Research suggests that social determinants of health, including poverty, unemployment, and limited education, contribute to health disparities. However, racism is a probable underlying determinant of these social conditions. This article uses a socioecological model to describe racism and its impact on African American women’s sexual and reproductive health. Although similar models have been used for specific infectious and chronic diseases, they have not described how the historical underpinnings of racism affect current sexual and reproductive health outcomes among African American women. We propose a socioecological model that demonstrates how social determinants grounded in racism affect individual behaviors and interpersonal relationships, which may contribute to sexual and reproductive health outcomes. This model provides a perspective to understand how these unique contextual experiences are intertwined with the daily lived experiences of African American women and how they are potentially linked to poor sexual and reproductive health outcomes. The model also presents an opportunity to increase dialog and research among public health practitioners and encourages them to consider the role of these contextual experiences and supportive data when developing prevention interventions. Considerations address the provision of opportunities to promote health equity by reducing the effects of racism and improving African American women’s sexual and reproductive health.

Introduction

Although public health efforts have made considerable progress in promoting health equity in the United States, studies suggest that African American women are disproportionately affected by multiple sexual and reproductive health conditions compared with women of other races/ethnicities.1,2 HIV and pregnancy-related complications remain within the top 10 leading causes of death for African American women aged 20–54 and 15–34 years, respectively.3 African American women accounted for 60% of the estimated new HIV infections that occurred among all women in 20144 and are 2.8–3.7 times more likely to die from pregnancy-related complications compared with women of all other races/ethnicities.5

To improve the sexual and reproductive health of African American women, several evidence-based prevention interventions have been developed and implemented.6 Although these interventions have been found to be efficacious in public health practice settings, research models are needed to address the underlying social determinants that directly and indirectly influence sexual and reproductive health disparities. We argue that racism, in both historical and contemporary contexts, is one condition that warrants more attention in models seeking to understand the sexual and reproductive health outcomes of African American women.

There is currently a dearth of research models that actually highlight the role of racism in sexual and reproductive health, with many studies focused on the reproductive (i.e., perinatal) health of African American women.7,8 Thus, we offer a socioecological model to provide a contextual understanding of the role of racism on the sexual and reproductive health outcomes of African American women and provide public health considerations that promote health equity. Socioecological models allow a better understanding of how social determinants such as racism influence health at individual, interpersonal, community, and societal levels.9,10 This article considers the context of race-specific experiences of African American women. A thorough understanding of how racism has facilitated disparate sexual and reproductive health outcomes may provide a foundation to appropriately address sexual and reproductive health issues within this population.

Levels of Racism and African American Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health

Racism is an institutionalized system of oppression that designates value to persons based on race/ethnicity.11 Jones delineates three levels of racism that contribute to health disparities. Institutional racism is characterized by large organizations or governments that impose practices that negatively affect access to health services, resulting in differences in the quality of healthcare for racial/ethnic minority groups. Personally mediated racism occurs when healthcare providers’ preconceived notions about racial groups result in the provision of substandard healthcare to racial/ethnic minorities. Last, internalized racism involves the embodiment and acceptance of stigmatizing messages from society by racially oppressed groups.11

We suggest that the three levels of racism play a key role in the trajectory of sexual and reproductive health experiences and outcomes of African American women. Many studies suggest that African American women are more likely than white women to experience discrimination,12 receive sub-standard medical care,13 and undergo unnecessary surgeries such as hysterectomies.2 These inequities are independent of socioeconomic status14 and access to quality medical care.13 Furthermore, at equal levels of socioeconomic status, insurance coverage, and healthcare access, African Americans receive lower quality medical care than white Americans.15 This suggests that race-based mistreatment may underlie racial disparities in sexual and reproductive health. Therefore, to address the effects of racism on sexual and reproductive health outcomes, it is important to understand how racism influences other social determinants of health.

Applying the Socioecological Model to Understand the Influence of Racism on African American Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health

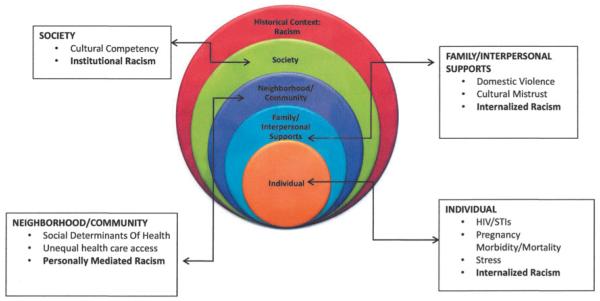

Socioecological models describe how individual, interpersonal, community, and societal factors shape population health.9 An underlying premise of this framework is that understanding these multiple levels of influence is necessary to avert health problems experienced by oppressed groups.16 We propose a multilevel model that describes the social determinants of health and important prevention opportunities (Fig. 1). Additionally, our model provides a framework to guide intervention planning, development, and implementation related to reducing risk factors and increasing protective factors related to sexual and reproductive health.

FIG. 1.

Socioecological model of African American women and sexual and reproductive health influences and outcomes.

The five-level socioecological framework presented is adapted from Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model for human development.9 The individual level, same as Bronfenbrenner’s, represents characteristics of the individual, including knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, and history. The family/interpersonal support level, parallel to Bronfenbrenner’s microsystem, describes familial and social networks of individuals, which may influence behavior and contribute to a range of experiences. Aligned with Bronfenbrenner’s mesosystem, the neighborhood/community level accounts for the environments in which individuals live. Last, the societal level considers factors such as institutionalized racism. In slight contrast to Bronfenbrenner’s macrosystem level (which describes the culture in which individuals live), and similar to the Alio et al. model devoted to infant mortality,7 the outer tier denotes the overall historical context of racism experienced by African American women, with the three levels of racism integrated across the model.

Individual level

African American women comprise the individual level of the proposed model. HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), pregnancy-related morbidity and mortality, stress, and internalized racism may be influenced by racism-related determinants (e.g., unemployment) that potentially increase risk.

HIV/STIs

Limited education, unemployment, lack of quality care, distrust of physicians, and negative perceptions of the healthcare system serve as barriers to HIV/STI prevention, treatment, and care. In 2014, African American women had an HIV diagnosis rate that was 18 times greater than white women.17 Furthermore, in 2012, African American women were more likely than white women to be diagnosed with having primary or secondary syphilis, gonorrhea, or chlamydia (16.3, 13.8, and 6.2 times, respectively).18 They are also twice as likely to be diagnosed with bacterial vaginosis, a correlate of poor pregnancy outcomes (e.g., low birth weight).19 For some African American women, racism continues to hinder optimal educational access, such that limited education is associated with poor HIV treatment adherence20 as well as unemployment, whereby some women may engage in sexual risk-taking behaviors to attain basic needs.21 Racism also affects women’s interactions with healthcare providers. For example, African American women living with HIV have expressed mistrust toward healthcare professionals.22 This may stem from knowledge about both historical experiences of African Americans interfacing with the healthcare system23 and current discriminatory practices from providers.24 Importantly, increased HIV risk among African American women has also been associated with the historical and contemporary role of mass incarceration of African American men.25

Pregnancy-related morbidity and mortality

Racism is a chronic stressor that not only contributes to HIV/STIs but can also directly affect the health of pregnant women and their children.26 African American women are also more likely than women of other races to experience pregnancy-related death.5,27,28 The black–white pregnancy-related mortality ratio ranged from 3.4 to 4 during 1998–2005.5 Additionally, infant mortality is more than twice as likely to occur among African Americans than whites.26,29 Racism-related factors associated with pregnancy-related mortality include economic vulnerability,30 stress,31,32 and experiences of discrimination.12,32,26

Stress

The relationship between stress and health outcomes has been well documented.33 Because racism is a form of stress, it may contribute to adverse health outcomes. Stress is associated with HIV-related discrimination, negative birth outcomes, and depression among African American women.24,34–36 Racism also fosters poverty, unemployment, and other social factors that increase the likelihood of experiencing stress.37 Furthermore, chronic stressors such as discrimination and poverty that occur over time may worsen health disparities because they can be experienced across generations38 and negatively affect social relationships that are known to be health protective.33

Internalized racism

Internalized racism can impact sexual and reproductive health by promoting psychological distress, substance use, and physical health conditions (e.g., glucose intolerance) that contribute to pregnancy-related complications39,40 as well as negatively affect behavioral decisions that may contribute to HIV/STI risk. For African American women, internalized racism may manifest in low self-worth, low self-confidence, and depression. These experiences may, in turn, foster behaviors that compromise the health of African American women.41 In addition, negative societal stereotypes targeting African American women can unfavorably affect their sexual health.42,43 The relationship between self-esteem and engaging in risky sexual behaviors44 may be evident among some African American women who internalize negative stereotypes.45 For example, a recent study suggested that young African American women who perceive negative sexual stereotypes in the media are more likely than others to have multiple sex partners.46

Family and interpersonal level

Family and interpersonal level factors associated with sexual and reproductive health outcomes include domestic and sexual violence, mass incarceration, and cultural mistrust. These factors may be influenced by historical racism and related experiences.

Domestic and sexual violence

Some researchers suggest that racism underlies much of the domestic violence that African American women experience because historically slavery promoted devaluation of African American women, strained African American male–female relationships, and provided little to no protection from sexual assault.47,48 More recently, it has been proposed that the intersection of domestic violence and HIV should be explored through the lens of historical racism due to a legacy of sexual stereotypes and negative images.43 When compared with white women, African American women have a significantly higher lifetime prevalence of rape, physical violence, and stalking by an intimate partner (34.6% among white women and 43.7% among African American women).49 These experiences have been associated with HIV acquisition among women50,51 and more frequent and more severe forms of domestic violence among women living with HIV.52 Additionally, domestic violence affects women’s decision-making pertaining to sexual behavior50,51,53,54 and is associated with psychological trauma,55 which can increase the likelihood that women experience sexual health problems (e.g., sexual dysfunction).56,57 These findings suggest that although domestic violence might be one determinant of HIV acquisition for African American women, it may be necessary to intervene from a sociocultural context that considers how historical factors related to domestic and sexual violence affect present-day sexual and reproductive health outcomes.

Mass incarceration

Racism has contributed to the extensive history of mass incarceration of African Americans following slavery. This continuum of incarceration has affected the familial structure, including access to education, housing and employment, and ultimately disparate health outcomes.25 Fullilove highlights the relationship between incarceration of African Americans and disproportionate rates of HIV.25 Thus, policy changes that affect disparate sentencing laws, encourage successful reentry into society, and address social determinants are needed.

Cultural mistrust

Cultural mistrust refers to African Americans’ tendencies to mistrust whites.58,59 Cultural mistrust has been associated with low self-esteem,60 dissatisfaction with healthcare,61,62 and delayed medical treatment.63 The legacy of medical mistreatment, scientific and medical experimentation, and sexualized violence against African American women likely continues to shape their mistrust of the medical profession. Indeed, one study found that cultural mistrust was linked to African American patients’ lack of satisfaction with their providers,64 while another study found patient dissatisfaction as one predictor of low antiretroviral therapy adherence among persons living with HIV.23

Neighborhood and community level

Neighborhood and community level factors influenced by racism affect the settings where African American women reside. Neighborhood characteristics (i.e., concentrated unemployment), unequal healthcare access, and personally mediated racism affect the health of women and their communities.65

Neighborhood characteristics

Neighborhood and community settings have historically been related to racism and potentially increase adverse health risks. These factors include, but are not limited to, concentrated unemployment, poverty, and under-resourced education. Throughout the past six decades, the unemployment rate for African Americans has remained approximately twice the rate experienced by whites.66 Health consequences associated with unemployment or insufficient income may include engaging in risky sexual behaviors in exchange for food or money for living expenses (i.e., rent).21,67 These behaviors place many African American women at risk for HIV/STIs.68,69 Additionally, poor health outcomes have been attributed to living in impoverished communities that are residentially segregated by race.70,71 Overall, limited education is associated with poor HIV treatment adherence, preterm births and infant mortality, living in poverty, and violence.20,29,67

Unequal healthcare access

Although healthcare segregation continued through the mid-1960s, the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was one attempt to grant African Americans with healthcare equal to that of whites. However, African Americans are more likely to be uninsured than whites and receive poorer quality medical care.13 Disparate access to and quality of care are underlying determinants of African American women’s disproportionately high HIV/STI burdens72 and poor perinatal outcomes.29

Personally mediated racism

Physicians’ unconscious attitudes and stereotypes have been associated with disparities in treatment recommendations for African American patients.73 Personally mediated racism has been experienced by African American women in their interaction with providers who project stereotypes of sexual promiscuity toward them and provide inferior service.73 Although it may be unconscious, this type of discrimination is associated with delayed reproductive health screenings, such as HIV treatment adherence, Pap smears, and mammograms.74,75

Societal level

Factors that facilitate racial and gender gaps at the societal level and impede healthy outcomes include cultural competence and institutional racism.

Cultural competence

Cultural competence encompasses behaviors, attitudes, and policies that allow medical establishments and providers to effectively serve clients of diverse racial/ethnic backgrounds.76 Patient-centered approaches that account for the process and delivery of healthcare are pertinent to culturally competent care and treatment. Medical providers’ lack of cultural competence has the potential to negatively affect the sexual and reproductive health of African American women because it can result in stigmatizing patient–provider interactions. Stigmatizing experiences may result in African Americans not being willing to be tested for HIV or receive medical services to prevent HIV acquisition and transmission.77

Institutional racism

Institutional racism reinforces personally mediated and internalized racism by promoting attitudes, practices, beliefs, and policies that give an advantage to whites and disadvantage to other racial groups.78 Although policies may be instrumental in creating societal change conducive to health equity, institutional racism is a root cause of racial disparities in health outcomes.13 Racially discriminatory policies affected healthcare access, treatment, and delivery of quality care, as well as housing, employment, and educational opportunities, and disparate sentencing laws toward African Americans. Historical and systemic healthcare barriers include accessibility and delivery of quality care by providers who are culturally and linguistically competent. Currently, the Affordable Care Act will allow individuals who were underinsured or uninsured to have access to quality care.79 While the long-term impact in healthcare settings is yet to be seen, early findings indicate the benefit of making health insurance available to many. Moreover, it has the potential to impact sexual and reproductive health outcomes by providing access to preventive care, including contraception, prenatal screenings, mammography, HIV/STI testing, and other sexual and reproductive health services.80,81 Additionally, policies that support equal access to quality education and employment will provide further opportunities to those who may not otherwise have access to adequate healthcare.82 Ultimately, structural changes that involve policy adjustments may ensure all members of society have opportunities that contribute to long-term health improvements.83

Historical context

Understanding the historical underpinnings of racism’s impact on the sexual and reproductive health of African American women provides context to current health outcomes. The historical and contemporary health and healthcare experiences of African American women provide a perspective that may be considered by healthcare providers and others who offer services and implement programs for African American women. Across the socioecological model, the historical context provides a framework to understand the relationship between health outcomes, social determinants, and experiences of racism within the lives of African American women. For example, at the societal level, experiences of sexual violence, including reproductive exploitation,48,84 medical experimentation,85 and policies targeting African American women, originated during slavery and were a form of institutional racism.7 Before the Civil Rights Act of 1964, legal segregation in healthcare as well as federally funded reproductive health procedures (i.e., coerced sterilizations) were commonly practiced.86 At the neighborhood and community level, experiences of poverty, concentrated unemployment, and residential segregation, which also had roots in slavery, are exacerbated by contemporary institutional and personally mediated racism. Although stereotypes regarding African American women as sexually promiscuous began during slavery, some women have internalized these images. Thus, it is important to ensure that the historical context is taken into consideration, particularly since these historical experiences have been shaped by sexual violence, medical mistreatment, and social injustice.84–86 Although healthcare has greatly improved since this time, African American women still experience varying levels of racism and discrimination that ultimately impact their current health and well-being.87

Conclusion

In this article, we offer a socioecological model that can be used to understand how racism underlies the social determinants of health and affects the sexual and reproductive health of African American women. In both historical and contemporary contexts, race-based mistreatment has been shown to place African American women at increased risk for HIV/STIs, pregnancy-related complications, and early mortality. Moreover, widespread health implications of racism are evident and exist at the individual, interpersonal, community, and societal levels. In this regard, African American women appear to be situated in contexts in which racism is rarely avoidable. A socioecological model that considers the historical influences of racism may improve understanding of the present-day sexual and reproductive health outcomes of African American women. In addition, such a model can strengthen reproductive justice efforts that acknowledge the historical context of sexual and reproductive mistreatment and promote social justice.

Although the purpose of our model was not focused on public health practice, per se, it does offer considerations that provide opportunities to promote health equity by reducing the effects of racism and improving African American women’s sexual and reproductive health. Because racism is present at multiple levels within the social environment, strategies across the socioecological model are necessary to address its broad impact and may prove to be more efficient and effective. In this study, we propose examples of public health considerations to help improve the sexual and reproductive health outcomes of African American women. It should be noted that these considerations are not exhaustive, yet provide key strategies that could be implemented. For example, individual-level interventions that seek to decrease African American women’s risk for HIV/STIs might also promote self-esteem in one-on-one or group-based interventions.88 This may work in conjunction with community-level interventions that provide quality educational and employment opportunities to inner-city residents.89 Economic incentives or microenterprise programs may also be viable options to increase employment opportunities for women.90 Coupling health interventions with employment programs not only addresses individual-level characteristics such as self-esteem and levels of stress exposure but may also address community outcomes.91 In addition, some African American women may need opportunities to increase their own understanding of the historical impact of racism and its links to contemporary health outcomes. This information might act as an impetus for further learning and support individual and community advocacy opportunities.

For the interpersonal level, interventions that involve family members can provide supportive opportunities to enhance the overall well-being of African American women. For example, interventions that involve partners of pregnant women might help reduce stress levels while also improving communication and coping skills. As mentioned above, there are numerous opportunities at the community level to improve health outcomes, specifically by developing partnerships that may facilitate structural changes. For example, rates of HIV are highest among African Americans and Hispanic/Latinos in communities where greater than 20% of persons lived below the poverty level and more than 8% did not have a high school diploma.92 Similar findings on socioeconomic correlates of HIV infection93 provide support for focusing interventions on social and structural determinants of health. These efforts not only help individuals but also address the social underpinnings of racism, which play a critical role in health outcomes and would likely be most effective in counteracting race-based mistreatment. In addition, efforts that acknowledge the role of mistrust of the healthcare system are better equipped to understand health-seeking behaviors and compliance matters.

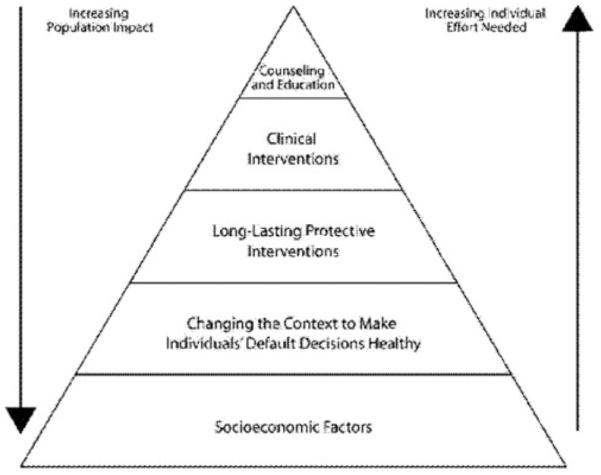

As discussed by Frieden’s health impact pyramid89 (Fig. 2), interventions that address societal-level factors have the greatest potential to achieve public health impact across disease outcomes and need governmental support to be effective. According to Frieden, although societal changes may be costly, the main obstacle to addressing these changes is a lack of political will.89 At a minimum, a systematic review of overarching health, economic, and education policies that may continue to disenfranchise African American women might be needed at this level. Since historically many policies were designed to further oppress and marginalize African American women, it is critical to examine how long-standing and even some contemporary statutes (i.e., welfare system, access to quality healthcare) ultimately impact the health and well-being of marginalized populations, including African American women. Provider and staff education and training to improve cultural competence to heighten sensitivity to the needs of African American women and to better understand the cultural norms and behaviors is also needed.94 Moreover, research focused on African American women should prioritize the role of racism and health disparities to sufficiently address the root causes of inequity. Implementing culturally tailored interventions may improve African American women’s health outcomes as well.95 Overall, strategies that support multisectorial partnerships at federal, state, and local levels may maximize the probability of implementing successful programs.96 Sexual and reproductive health equity, based on evaluation data of interventions and demonstration projects, can be achieved with a commitment to effectively address racism and other underlying social determinants that promote health disparities.

FIG. 2.

The health impact pyramid.

Footnotes

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions of this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Armstrong A, Maddox YT. Health disparities and women’s reproductive health. Ethn Dis. 2007;17:S24–S27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bower JK, Screiner PJ, Sternfield B, Lewis CE. Black-White differences in hysterectomy prevalence: The CARDIA study. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:300–307. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.133702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Assessed May 19, 2016];Leading Causes of Death by Age Group, Black Females-United States. 2013 http://www.cdc.gov/women/lcod/2013/womenblack_2013.pdf.

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Accessed May 5, 2016];HIV Surveillance Report. 2014 26 http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/surveillance/. Published November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berg C, Callaghan WM, Syverson C, Henderson Z. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 1998 to 2005. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:1302–1309. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181fdfb11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . In: Compendium of evidence-based interventions and best practices for HIV prevention. Services DoHaH, editor. Atlanta, GA: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alio A, Richman A, Clayton H, Jeffers D, Wathington D, Salihu H. An ecological approach to understanding black-white disparities in perinatal mortality. Matern Child Health J. 2010;14:557–566. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0495-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hogue CJR, Bremner JD. Stress model for research into preterm delivery among black women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:S47–S55. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.01.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bronfenbrenner U. International Encyclopedia of Education. 2nd ed Vol. 3. Elsevier; Oxford: 1994. Ecological models of human development. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of developmental processes in handbook of child psychology. 5th ed Vol. 1. John Wiley and Sons, Inc.; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones CP. Levels of racism: A theoretic framework and a gardener’s tale. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:1212–1215. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.8.1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collins JW, David RJ, Handler A, Wall S, Andes S. Very low birthweight in African American infants: The role of maternal exposure to interpersonal racial discrimination. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:2132–2138. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.12.2132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR. Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams DR. Race, socioeconomic status, and health—The added effects of racism and discrimination. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;896:173–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: Evidence and needed research. J Behav Med. 2009;32:20–47. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krieger N. Theories for social epidemiology in the 21st century: An ecosocial perspective. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;3:668–677. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.4.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Accessed May 5, 2016];HIV Surveillance Report. 2014 26 http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/surveillance/. Published November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2012. Department of Health and Human Services; Atlanta, GA: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kehrer BH, Wolin CM. Impact of income maintenance on low birth weight: Evidence from the Gary Experiment. J Hum Res. 1979;14:434–462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalichman SC, Catz S, Ramachandran B. Barriers to HIV/AIDS treatment and treatment adherence among African-American adults with disadvantaged education. J Natl Med Assoc. 1999;91:439–446. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DiNenno EA, Oster AM, Sionan C, Denning P, Lansky A. Piloting a system for behavioral surveillance among heterosexuals at increased risk of HIV in the United States. Open AIDS J. 2012;6:169–176. doi: 10.2174/1874613601206010169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abrums M. “Jesus will ®x it after awhile”: Meanings and health. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50:89–105. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00277-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roberts KJ. Physician-patient relationships, patient satisfaction, and antiretroviral medication adherence among HIV-infected adults attending a public health clinic. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2002;16:43–50. doi: 10.1089/108729102753429398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ, Mikhail I, et al. HIV discrimination and the health of women living with HIV. Women Health. 2007;46:99–112. doi: 10.1300/J013v46n02_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fullilove RE. Mass incarceration in the United States and HIV/AIDS: Cause and effect? Ohio State. J Criminal Law. 2011;9:353–361. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giscombe CL, Lobel M. Explaining disproportionately high rates of adverse birth outcomes among African Americans: The impact of stress, racism and related factors in pregnancy. Psychol Bull. 2005;131:662–683. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.5.662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berg C, Harper MA, Atkinson SM, et al. Preventability of pregnancy-related deaths: Results of a state-wide review. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:1228–1234. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000187894.71913.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tucker MJ, Berg CJ, Callaghan WM, Hsia J. The black-white disparity in pregnancy-related mortality from 5 conditions: Differences in prevalence and case fatality rates. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:247–251. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.072975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu MC, Kotelchuck M, Hogan V, Jones L, Wright K, Halfon N. Closing the black-white gap in birth outcomes: A life-course approach. Ethn Dis. 2010;20(Suppl 2):s262–s276. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh GK. In: Maternal mortality in the United States, 1935–2007: Substantial racial/ethnic, socioeconomic, and geographic disparities persist. A 75th anniversary publication. Services DoHaH, editor. Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau; Rockville, MD: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosenthal L, Lobel M. Explaining racial disparities in adverse birth outcomes: Unique sources of stress for Black American women. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72:977–983. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Geronimus AT. The weathering hypothesis and the health of African-American women and infants: Evidence and speculations. Ethn Dis. 1992;2:207–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pearlin LI, Schieman S, Fazio EM, Meersman SC. Stress, health, and the life course: Some conceptual perspectives. J Health Soc Behav. 2005;46:205–219. doi: 10.1177/002214650504600206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stancil TR, Hertz-Picciotto I, Schramm M, Watt-Morse M. Stress and pregnancy among African American women. Paedeatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2000;14:127–135. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2000.00257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lobel M, Graham J, DeVincent C, Schneider J, Meyer BA. Pregnancy-specific stress, prenatal health behaviors, and birth outcomes. Health Psychol. 2008;27:604–615. doi: 10.1037/a0013242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Geronimus AT, Hicken M, Keene D, Bound J. “Weathering” and Age patterns of allostatic load scores among Blacks and Whites in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:826–833. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.060749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Williams DR, Jackson PB. Social sources of racial disparities in health. Health Affairs. 2005;24:325–334. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thoits PA. Stress and health major findings and policy implications. J Health Soc Behav. 2010;51:S41–S53. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kwate NM, Valdimarsdottir HB, Guevarra JS, Bovbjerg DH. Experiences of racist events are associated with negative health consequences for African American women. J Natl Med Assoc. 2003;95:450–460. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tull ES, Chambers EC. Internalized racism is associated with glucose intolerance among black Americans in the U.S. Virgin Islands. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1498. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.8.1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perry BL, Stevens-Watkins D, Oser CB. The moderating effects of skin color and ethnic identity affirmation on suicide risk among low-SES African American women. Race Soc Probl. 2013;5:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s12552-012-9080-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Collins PH. Black sexual politics: African Americans, gender, and the new racism. Routledge; New York: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lichenstein B. Domestic violence, sexual ownership, and HIV risk in women in the American deep south. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:701–714. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pittiglio L, Jackson F, Florio A. The relationship of self-esteem and risky sexual behaviors in young African-American women. J Natl Black Nurses Assoc. 2012;23:16–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thomas AJ, Witherspoon KM, Speight SL. Toward the development of the stereotypic roles for Black Women Scale. J Black Psychol. 2004;30:426–442. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peterson S, Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ, Harrington K, Davies S. Images of sexual stereotypes in rap videos and the health of African American female adolescents. J Womens Health. 2007;16:1157–1164. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krieger N. The ostrich, the albatross, and public health: An ecosocial perspective—Or why an explicit focus on health consequences of discrimination and deprivation is vital for good science and public health practice. Public Health Rep. 2001;116:419–423. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.5.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smithers G. Slave breeding: Sex, violence and memory in African American history. University Press of Florida; Gainesville, Florida: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Breiding MJ, Chen J, Black MC. In: Intimate partner violence in the United States—2010. DHHS, editor. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; Atlanta, GA: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wyatt GE, Myers HF, Williams JK, et al. Does a history of trauma contribute to HIV risk for women of color? Implications for prevention and policy. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:660–665. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.4.660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Clum GA, Andrinopoulos K, Muessig K, Ellen JM. Child abuse in young, HIV-positive women: Linkages to risk. Qual Health Res. 2009;19:1755–1768. doi: 10.1177/1049732309353418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guinan M. Black communities’ belief in “AIDS as Genocide”—A barrier to overcome for HIV prevention. Ann Epidemiol. 1993;3:193–195. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(93)90136-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wyatt GE, Hamilton AB, Myers HF, et al. Violence prevention among HIV-positive women with histories of violence: Healing women in their communities. Womens Health Issues. 2011;21(6 Suppl):S255–S260. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sareen J, Pagura J, Grant B. Is intimate partner violence associated with HIV infection among women in the United States? Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31:274–278. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Banyard VL, Williams LM, Siegel JA. The long-term mental health consequences of child sexual abuse: An exploratory study of the impact of multiple traumas in a sample of women. J Trauma Stress. 2001;14:697–715. doi: 10.1023/A:1013085904337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wyatt G. The sociocultural context of African American and white American women’s rape. J Soc Issues. 1992;48:77–91. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chyu L, Upchurch DM. Racial and ethnic patterns of allostatic load among adult women in the United States: Findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2004. J Womens Health. 2011;20:575–583. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Terrell F, Taylor J, Menzise J, Barrett RK. Cultural mistrust. A core component of African American consciousness. In: Neville HA, Tynes BM, Utsey SO, editors. The Handbook of African American Psychology. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, California: 2009. pp. 299–309. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Terrell F, Terrell SL. An inventory to measure cultural mistrust among Blacks. West J Black Stud. 1981;5:180–184. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Phelps RE, Taylor JD, Gerard PA. Cultural mistrust, ethnic identity, racial identity, and self-esteem among ethnically diverse Black university students. J Counsel Dev. 2001;70:209–216. [Google Scholar]

- 61.LaVeist TA, Carroll T. Race of physician and satisfaction with care among African American patients. J Natl Med Assoc. 2002;94:937–943. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.LaVeist TA, Nuru-Jeter A. Is doctor-patient race concordance associated with greater satisfaction with care? J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43:296–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Thompson HS, Valdimarsdottir HB, Winkel G, et al. The group-based medical mistrust scale: Psychometric properties and association with breast cancer screening. Prev Med. 2004;38:209–218. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Benkert R, Peters R, Clark R, Keves-Foster K. Effects of perceived racism, cultural mistrust and trust in providers on satisfaction with care. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98:1532–1540. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vaughan AS, Rosenberg E, Luke Shouse RL, Sullivan PS. Connecting race and place: A county-level analysis of White, Black, and Hispanic HIV prevalence, poverty, and level of urbanization. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:e77–e84. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.U.S. Department of Labor . In: The African-American labor force in the recovery. Labor USDo, editor. GPO; Washington, DC: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Krishnan S, Dunbar MS, Minnis AM, Medlin CA, Gerdts CE, Padian NS. Poverty, gender inequities, and women’s risk of human immunodeficiency virus/AIDS. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1136:101–110. doi: 10.1196/annals.1425.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stratford D, Mizuno Y, Williams K, Courtenay-Quirk C, O’Leary A. Addressing poverty as risk for disease: Recommendations from CDC’s consultation on microenterprise as HIV prevention. Public Health Rep. 2008;123:9–20. doi: 10.1177/003335490812300103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tsui EK, Leonard L, Lenoir C, Ellen JM. Poverty and sexual concurrency: A case study of STI risk. J Health Care Poor and Underserved. 2008;19:758–777. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.LaVeist TA. Segregation, poverty, and empowerment: Health consequences for African Americans. Milbank Q. 1993;71:41–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sznycer-Taub M. Residential racial segregation and its impact on HIV/AIDS transmission and testing. 2009. Unpublished manuscript.

- 72.Parrish DD, Kent CK. Access to care issues for African American communities: Implications for STD disparities. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35:S19–S22. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31818f2ae1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.van Ryn M, Burgess DJ, Dovidio JF, et al. The impact of racism on clinician cognition, behavior, and clinical decision making. Du Bois Rev. 2011;8:199–218. doi: 10.1017/S1742058X11000191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mouton CP, Carter-Nolan PL, Makambi KH, Taylor TR, Palmer JR, Adams-Campbell LL. Impact of perceived racial discrimination on health screening in Black Women. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21:287–300. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Boarts JM, Bogart LM, Tabak MA, Armelie AP, Delahanty DL. Relationship of race-, sexual orientation-, and HIV-related discrimination with adherence to HIV treatment: A pilot study. J Behav Med. 2008;31:445–451. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Anderson LM, Scrimshaw SC, Fullilove MT, Fielding JE. Culturally competent healthcare systems. A systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24(3S):68–79. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00657-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.George S, Duran N, Norris K. A systematic review of barriers and facilitators to minority research participation among African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:e16–e31. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jones CP. Confronting institutionalized racism. Phylon. 2003;50:7–22. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . In: Births: 2007. Unpublished estimates. DHHS, editor. National Center for Health Statistics: National Vital Statistics System; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) In: The Affordable Care Act and African Americans Fact Sheet. Services USDoHaH, editor. Washington, DC: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) In: The Affordable Care Act and Women. DHHS, editor. Washington, DC: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Marmot M. Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet. 2005;365:1099–1104. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71146-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Blankenship KM, Friedman SR, Dworkin S, Mantell JE. Structural interventions: Concepts, challenges and opportunities for research. J Urban Health. 2008;83:59–72. doi: 10.1007/s11524-005-9007-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Donoghue E. Black breeding machines: The breeding of negro slaves in the diaspora. AuthorHouse; Indiana: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Savitt TL. The use of blacks for medical experimentation and demonstration in the old south. J South Hist. 1982;48:331–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Roberts D. Killing the black body: Race, reproduction and the meaning of liberty. Pantheon Books; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Slaughter-Acey JC, Caldwell CH, Misra DP. The influence of personal and group racism on entry into prenatal care among African American women. Womens Health Issues. 2013;23:381–387. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Prather C, Fuller TR, King W, et al. Diffusing an HIV prevention intervention for African American Women: Integrating afrocentric components into the SISTA Diffusion Strategy. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006;18(4 Suppl A):149–160. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.supp.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Frieden T. A framework for public health action: The health impact pyramid. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:590–595. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.185652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Prather C, Marshall K, Courtenay-Quirk C, et al. Addressing poverty and HIV using microenterprise: Findings from qualitative research to reduce risk among unemployed or underemployed African American women. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23:1266–1279. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2012.0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sherer RD, Bronson JD, Teter CJ, Wykoff RF. Microeconomic loans and health education to families in impoverished communities: Implications for the HIV pandemic. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care. 2004;3:110–114. doi: 10.1177/154510970400300402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Finer LB, Zolna MR. Unintended pregnancy in the United States: Incidence and disparities. Contraception. 2011;84:478–485. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hasnain M, Levy JA, Mensah EK, Sinacore JM. Association of educational attainment with HIV risk in African American active injection drug users. AIDS Care. 2007;19:87–91. doi: 10.1080/09540120600872075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Myers H. Ethnicity- and socio-economic status-related stresses in context: an integrative review and conceptual model. J Behav Med. 2009;32:9–19. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9181-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Nobles W, Goddard L, Gilbert D. Culturecology, women, and African-centered HIV prevention. J Black Psychol. 2009;35:228–246. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Office of National AIDS Policy . In: National HIV/AIDS Stratetegy for the United States. House W, editor. The White House Office of National AIDS Policy; Washington, DC: 2010. [Google Scholar]