Abstract

Objective:

To determine the incidence, timing, and severity of neurologic findings in acute HIV infection (pre–antibody seroconversion), as well as persistence with combination antiretroviral therapy (cART).

Methods:

Participants identified with acute HIV were enrolled, underwent structured neurologic evaluations, immediately initiated cART, and were followed with neurologic evaluations at 4 and 12 weeks. Concurrent brain MRIs and both viral and inflammatory markers in plasma and CSF were obtained.

Results:

Median estimated HIV infection duration was 19 days (range 3–56) at study entry for the 139 participants evaluated. Seventy-three participants (53%) experienced one or more neurologic findings in the 12 weeks after diagnosis, with one developing a fulminant neurologic manifestation (Guillain-Barré syndrome). A total of 245 neurologic findings were noted, reflecting cognitive symptoms (33%), motor findings (34%), and neuropathy (11%). Nearly half of the neurologic findings (n = 121, 49%) occurred at diagnosis, prior to cART initiation, and most of these (n = 110, 90%) remitted concurrent with 1 month on treatment. Only 9% of neurologic findings (n = 22) persisted at 24 weeks on cART. Nearly all neurologic findings (n = 236, 96%) were categorized as mild in severity. No structural neuroimaging abnormalities were observed. Participants with neurologic findings had a higher mean plasma log10 HIV RNA at diagnosis compared to those without neurologic findings (5.9 vs 5.4; p = 0.006).

Conclusions:

Acute HIV infection is commonly associated with mild neurologic findings that largely remit while on treatment, and may be mediated by direct viral factors. Severe neurologic manifestations are infrequent in treated acute HIV.

Although HIV can cross into the CNS within days of systemic infection,1 little is known about the vulnerable neuroanatomy or neurologic presentation of acute HIV, the first days to weeks after infection. Presently, the literature on the early neuroclinical events in HIV infection is skewed towards instances of fulminant neurologic involvement. Cases of Bell palsy2,3 have been reported, as well as the more serious sequelae of Guillain-Barré syndrome,4 optic neuritis,5 encephalitis,6,7 myelopathy,8 and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis.9,10 While these neurologic events likely occurred in the weeks and months following infection, it is unclear that these represent the typical neurologic experience following HIV infection. A study of community-identified individuals with primary HIV infection, generally defined as within the first year of exposure, examined the incidence of prominent neurologic findings, and reported 12 of 290 cases (4.1%) experiencing any neurologic presentation.11 Without systematic neurologic assessments of participants from a known catchment area, true frequency of neurologic findings cannot be assessed, and the full spectrum of neurologic involvement in acute HIV may be overlooked.

To better identify the neuroclinical events in acute HIV infection, we prospectively characterized the incidence, timing, and severity of neurologic findings in individuals with a laboratory-screened diagnosis of acute HIV, using structured neurologic evaluations across the first 12 weeks following diagnosis and treatment. Most participants were systematically captured from individuals voluntary accessing HIV testing, allowing for estimates of the incidence of neurologic findings during acute HIV.

METHODS

Participants.

We included individuals diagnosed with acute HIV infection from the Southeast Asia Research Collaboration with the University of Hawaii (SEARCH) 010/RV254 cohort in Bangkok, Thailand, described previously.12 Participants electively sought testing at the Thai Red Cross Anonymous HIV clinic in Bangkok, and were identified in acute HIV using hierarchical algorithms from pooled nucleic acid and sequential enzyme immunoassay (EIA) testing. Exclusion criteria include age <18 years, positive urine pregnancy test, major medical or psychiatric disorders, or chronic HIV. Of the 108,099 samples screened for inclusion between May 14, 2009, and July 31, 2014, 236 cases of acute HIV infection (Fiebig I–V)13 were identified, of which 189 entered the parent study and 134 had complete neurologic data. We also enrolled 8 additional participants screened through a separate study, the Early Capture HIV Cohort Center in Pattaya, Thailand, where high-risk individuals were tested for HIV every 3 days. Three of these participants were excluded due to incomplete data. Estimated infection duration was determined either by self-report of a single exposure date or, for participants with multiple potential exposures, calculated as a median of these dates. Plasma biomarkers of HIV infection were obtained at study entry and participants were confirmed to be in Fiebig stages I–V of acute HIV, per published guidelines.12 One participant who enrolled in Fiebig V was later reclassified as Fiebig VI due to subsequent narrowing of assay thresholds, and was retained in the study.

At study entry, the presence of acute retroviral syndrome (ARS) was determined by a HIV-trained physician using a standardized checklist of qualifying symptoms, requiring ≥3 to occur in the timeframe of estimated infection and diagnosis. The presence of illicit drug use was assessed in a structured interview and reflected any self-reported use within 4 months preceding diagnosis. Participants completed a validated Thai version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS),14 with depression (HADS-D) or anxiety (HADS-A) determined by either borderline abnormal (8–10) or abnormal (11–21) subscores, per the original, validated ranges.15 To minimize the influence of other study elements, the psychiatric self-assessments were completed first, followed by medical and neurologic evaluations, blood collection, neuropsychological testing, and then MRI and lumbar puncture. After initial assessments, participants then started either a combination antiretroviral therapy regimen (cART) composed of efavirenz, tenofovir, and either emtricitabine or lamivudine, or the cART regimen augmented with antiretrovirals maraviroc and raltegravir (cART+),16 as part of the parent study. Following HIV diagnosis, expedited evaluations were typically completed within 48 hours, and 94% of participants initiated therapy within 3 days of identification (range 0–5 days; median 0 days).

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

We received study approval from institutional review boards at UCSF, Yale University, Chulalongkorn University, and the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, and all participants provided written, informed consent for research.

Neurologic characterization.

Structured neurologic interviews and examinations that were based on the AIDS Clinical Trials Group Macroneurological Examination17 were performed at study entry by HIV-trained physicians (J.L.K.F., E.K., J.A., N.P.). These were repeated at 4 and 12 weeks after initiating cART. Self-reported cognitive and neurologic symptoms were assessed through standardized questions, with participants' responses rated by degree of functional impairment. Findings in neurologic examinations reflect standardized scoring; for example, finger taps were rated as normal if 15 or more were completed in 5 seconds. A brief neuropsychological testing battery was completed, comprising the Grooved Pegboard test in nondominant hand (fine motor function), Color Trails 1 and Trail Making A (psychomotor speed), and Color Trails 2 (executive functioning/set-shifting), as previously reported.18 To calculate an overall measure of cognitive function based on a mean of z-scores (NPZ-4), raw neuropsychological testing results were standardized to healthy Thai control data.19 Lumbar punctures were completed at study entry on 24% of participants, with the lower limit of detection of CSF HIV RNA of 100 copies/mL. T1-weighted and T2-weighted fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) MRI brain scans were electively obtained at study entry on the same 1.5T GE scanner, and were independently interpreted by 2 separate neuroradiologists (S.L. and J.N.).

Analyses.

Univariate analyses were reported as frequencies and percents, and means were used for continuous data. Comparisons between groups were performed using 2-tailed unpaired t tests for continuous data, and Mann-Whitney U tests were employed for ordinal data. χ2 analyses were performed comparing proportions between groups. Analyses were performed on Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) and used p ≤ 0.05 for statistical significance. Effect sizes are reported as r2 for t tests and φ for χ2 tests.

RESULTS

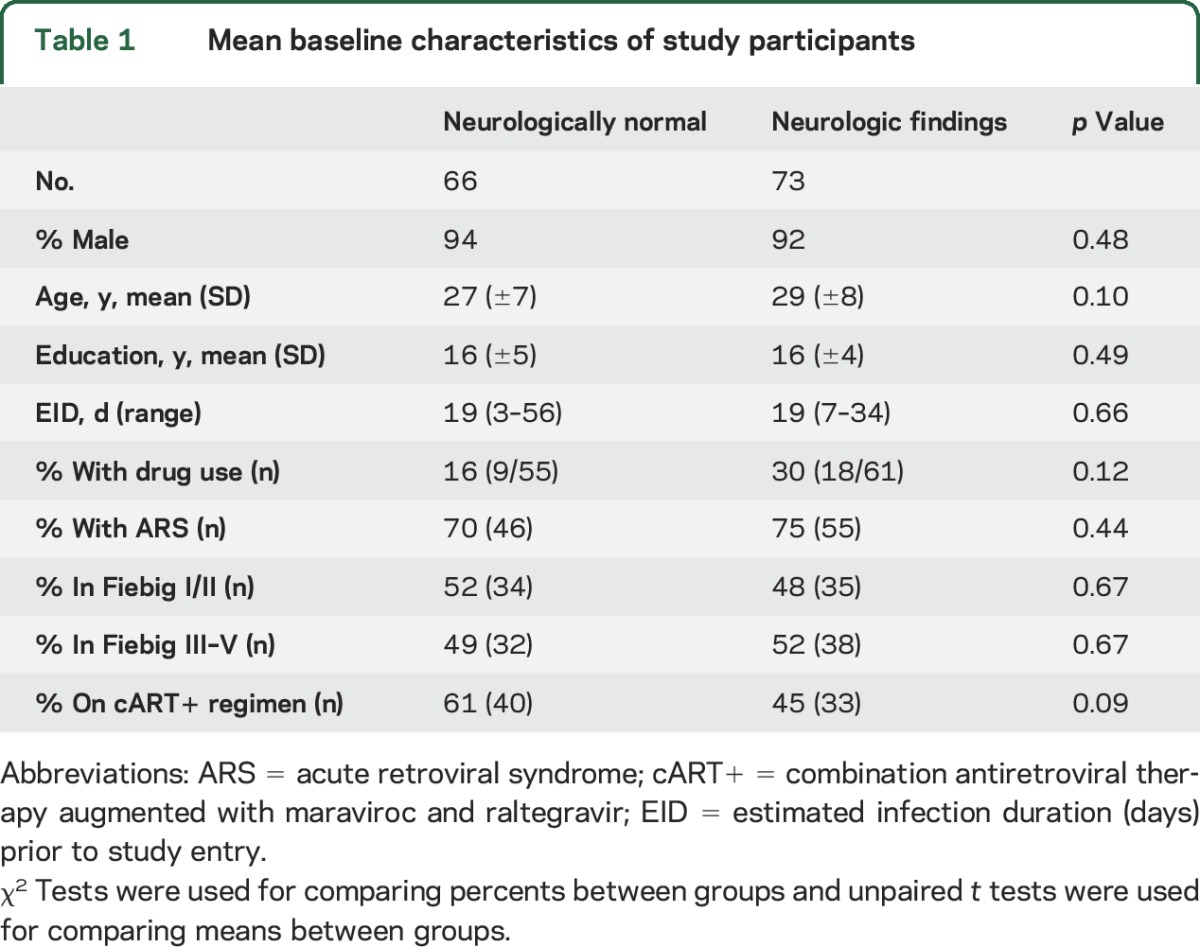

For the 197 individuals enrolled in the parent cohort between May 14, 2009, and July 31, 2014, we identified 139 with complete data. Of the 58 excluded participants, 1 left the study, 51 had incomplete neurologic examination data, and 7 were excluded due to incomplete demographic information. No participants were lost to follow-up. Excluded individuals differed from study participants only by age (31 vs 28 years, p = 0.01), but not other demographic factors. Men comprised 93% of participants, and 98% of these identified their risk for infection as having sex with men. Three participants were transgender women. On average, the estimated HIV infection duration at study entry was 19 days (range 3–56 days) and the mean education was 16 years (table 1). For participants with HIV subtype testing (n = 134), 81% were infected with HIV-1 subtype CRF01-AE.

Table 1.

Mean baseline characteristics of study participants

Neurologic symptoms and examination findings.

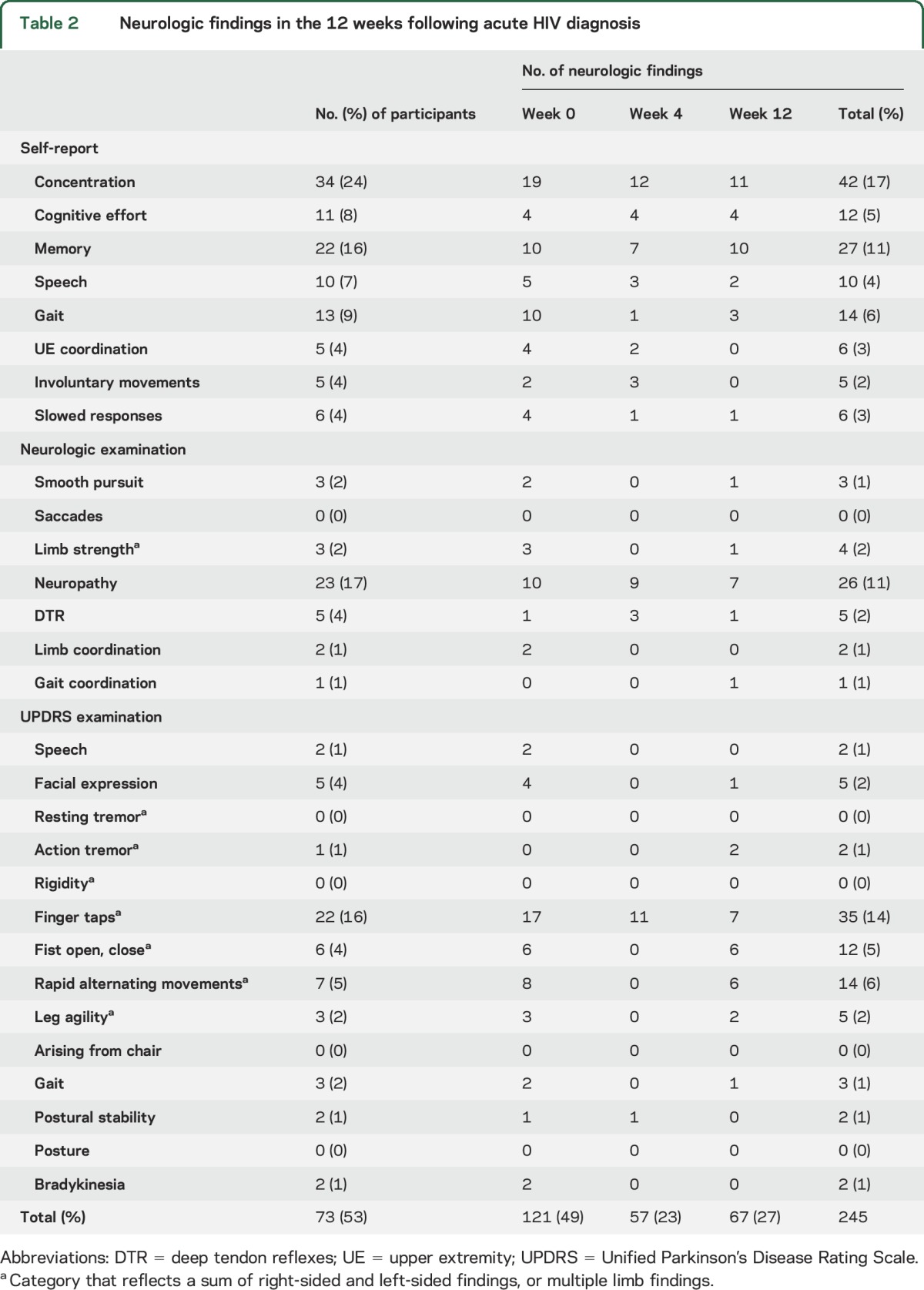

One or more neurologic findings were reported or identified in 73 of 139 participants (53%) within the first 12 weeks following acute HIV diagnosis, including one individual with a fulminant neurologic presentation of HIV, Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) (table 1). Of the 245 individual neurologic findings identified in 73 participants, 122 were neurologic or cognitive symptoms self-reported during the structured neurologic interview, and 123 were objective neurologic examination findings (table 2). Age, sex, drug use, estimated infection duration, Fiebig stage, and being on the augmented cART arm of the parent protocol were not associated with overall presence or absence of neurologic findings.

Table 2.

Neurologic findings in the 12 weeks following acute HIV diagnosis

Cognitive complaints reflected 33% of neurologic findings in acute HIV, including increased cognitive effort, problems with memory, and difficulty concentrating. To explore the possible contribution of affective symptoms to self-reported cognitive symptoms, we examined associations with available HADS completed at weeks 0, 4, and 12 (n = 120). The presence of any cognitive complaints within the first 12 weeks after HIV diagnosis did not correlate with presence or absence of abnormal depression on the HADS-D (χ2 = 0.9; p = 0.35) in that time, although when examining the HADS-D as a continuous variable, participants reporting cognitive symptoms did have higher average HADS-D scores (5.3 vs 3.9; p = 0.01, r2 = 0.05). In contrast, cognitive complaints within the first 12 weeks following diagnosis did correlate with the presence of abnormal anxiety on the HADS-A (χ2 = 4.1; p = 0.04, φ = 0.18) during that time, but those with cognitive complaints had similar average HADS-A scores (7.2 vs 6.2; p = 0.09) compared to individuals not reporting cognitive symptoms. To explore whether any self-report of cognitive complaints coincided with objective cognitive deficits, we examined participants with neuropsychological testing data. When comparing participants' composite NPZ-4, those with any cognitive complaints across the first 12 weeks of HIV diagnosis had lower, thus more impaired, cognitive functioning at week 0 (−0.24 vs 0.06, p = 0.01, r2 = 0.05; n = 38, n = 79), week 12 (0.09 vs 0.52, p = 0.001, r2 = 0.13; n = 23, n = 58), and week 24 (0.001 vs 0.45, p = 0.05, r2 = 0.06; n = 23, n = 52) compared to participants without any cognitive complaints.

Motor findings detected on the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) elements in the macroneurologic examination comprised 34% (n = 82) of all neurologic findings, and primarily reflected a slowing of fine finger and hand movements. No instances of resting tremor, rigidity, or postural change were observed. Over 11% (n = 26) of all neurologic findings in acute HIV were due to neuropathy, affecting 17% of participants, and aside from the case of GBS, all neuropathy was in a distal sensory pattern. To examine whether injury from peripheral neuropathy contributed to the observed motor slowing, we reviewed the 22 participants with any finger tap abnormalities across the first 12 weeks after diagnosis. Only 3 had any neuropathy in that time, and only 2 of these had co-occurring neuropathy at visits where finger tap abnormalities were found.

The individual who developed GBS had presumed dengue fever over a month prior to HIV diagnosis, and subsequently experienced a defined, HIV-attributable antiretroviral syndrome. The participant presented in acute HIV Fiebig III stage with a particularly low CD4 count of 7 cells/mm3 that increased to 180 cells/mm3 after 4 weeks on the standard cART regimen. The neurologic examination revealed no deficits through the week 4 visit; however, 3 days later, he developed reduced proximal arm strength. Within 48 hours, there were ascending distal paresthesias, followed by diffuse areflexia and weakness in the lower extremities. The participant was hospitalized and given a diagnosis of GBS, supported by nerve conduction and CSF studies. He was treated with 2 mg/kg of IV immunoglobulins over 5 days. At most extreme, the participant experienced facial diplegia and profound limb weakness and sensory deficits. After discharge, he progressively improved, with return to normal function in 6 months. Fifteen months after GBS diagnosis, he remained functionally normal, with persistent areflexia in the arms, diminished reflexes in the left leg, and mildly decreased vibratory sense distally.

Timing of neurologic findings and change concurrent with cART.

Nearly half of all neurologic findings in acute HIV occurred at the initial visit (49%; n = 121), just prior to the initiation of cART. Concurrent with 4 weeks on treatment, 90% (n = 110) of the neurologic findings that were present at diagnosis had remitted. Participants on the augmented cART+ regimen experienced a similar average number of neurologic findings across the week 4 and 12 evaluations, after therapy was started, compared to those on the cART regimen (0.75 vs 0.98, p = 0.36). Only 9% (n = 22) of all neurologic findings reported in the first 12 weeks remained at 24 weeks after diagnosis, and these tended towards self-reported cognitive symptoms (n = 10), with the case of GBS accounting for 6 of 9 persisting neurologic examination abnormalities.

Severity of neurologic findings.

Almost all neurologic findings in acute HIV infection were reported as slight or mild in severity (96%; n = 236), such as a diminished capacity for concentration without impacting overall function. Of the 3% (n = 8) of neurologic findings reported as moderate in severity, 6 of 8 findings were present at the week 0 visit, just prior to initiation of cART, and 7 of 8 reflected motor findings (e.g., incoordination, slowed movements, postural instability). The only severe neurologic finding was leg weakness in the patient with resolving GBS.

Comparison between participants with and without neurologic findings.

The 73 participants with at least one neurologic finding in acute HIV were found to have a higher average plasma viral load (log10 HIV RNA) at diagnosis compared to the 66 participants without neurologic findings (5.9 vs 5.4; p = 0.006, r2 = 0.05). There were no differences in their initial clinical severity of HIV, as reflected by average number of ARS symptoms (5.9 vs 4.9, p = 0.09; n = 138). No differences were found between participants with and without neurologic findings in terms of CSF log10 HIV RNA (3.7 vs 3.1, p = 0.14; n = 32); plasma CD4 (339 vs 381 cells/mm3, p = 0.46; n = 139); plasma neopterin, a marker of macrophage activation (2,307 vs 2,193 pg/mL, p = 0.69; n = 55); or CSF neopterin (1,948 vs 1,986 pg/mL, p = 0.67; n = 26).

Six participants were found to have CSF HIV RNA below detection limits of our assay at the time of presentation, 2 of whom had no neurologic findings. However, 4 individuals with undetectable CSF HIV RNA had a total of 5 neurologic findings possibly attributable to CNS anatomy, including increased cognitive effort, difficulty with concentration, decreased facial expression, postural instability, and upper extremity incoordination.

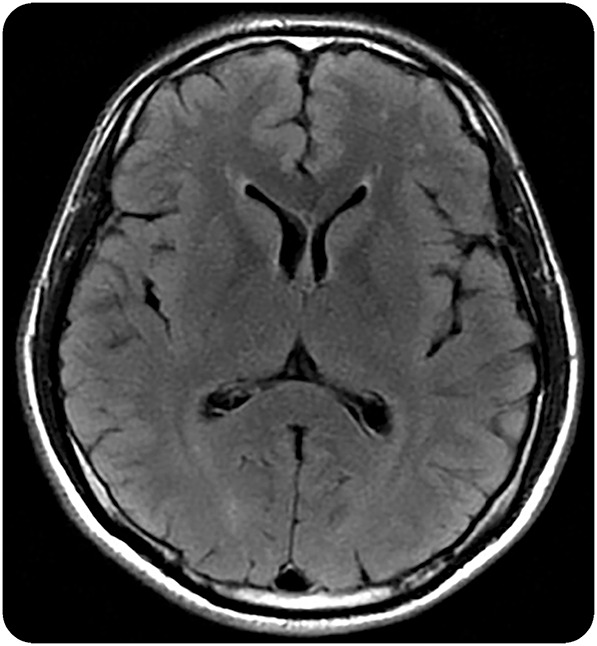

We did not identify T1-weighted or T2 FLAIR abnormalities among the 62 participants with MRI scans at diagnosis, which included 35 individuals with neurologic findings. Five individuals had mild white matter hyperintensities (figure).

Figure. Representative mild white matter hyperintensities on T2 FLAIR.

Axial T2-weighted fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) MRI brain sequence from a 37-year-old Thai man in Fiebig stage I of acute HIV infection, estimated 14 days postinfection. Punctate white matter T2 hyperintensities in the right and left frontal subcortical white matter were noted. A follow-up MRI brain after 6 months of antiretroviral therapy was unchanged.

DISCUSSION

This study identifies that mild neurologic findings are common in the months following acute HIV diagnosis when antiretroviral therapy is promptly initiated, with mild cognitive complaints, motor findings, and neuropathy occurring most frequently. With rapid treatment, only rare fulminant neurologic involvement was observed in this sample.

Cognitive complaints were frequent in acute HIV, and the presence of cognitive complaints correlated with the presence of abnormal anxiety on the HADS-A. Although several studies have found no group deficits on neuropsychological testing in early or acute HIV,18,20 we found that the subset of patients with acute HIV with initial cognitive complaints had lower neuropsychological test z scores across the first 6 months following diagnosis. These scores fell within a normal range for both groups, and all clinical changes were small. The measurably lower performance in those with cognitive complaints may instead have mechanistic relevance, reflecting an initial process whereby HIV impacts brain functioning. These findings were observed in participants in acute HIV with early treatment intervention, and it is unknown whether a common underlying mechanism could cause progressive neuropsychological decline in those without rapid treatment.

The UPDRS portion of a standard HIV neurologic examination identified a mild bradykinesia occurring in acute HIV, and may imply a selective vulnerability in extrapyramidal neuroanatomy early in infection. While fulminant parkinsonism is a rare presentation of primary HIV,21 magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) data implicate an anatomical basis for extrapyramidal involvement in acute HIV infection, with a trend towards elevated markers of inflammation (e.g., choline/creatinine) in the basal ganglia compared to controls.1 However, this macroneurologic examination was not designed for acute HIV, instead aiming to capture UPDRS components of parkinsonism described in chronic HIV,17,22 and the mild upper extremity bradykinesia may reflect neural network dysfunction elsewhere in the motor system.23 Other possible localizations include inflammation in frontal white matter, which has been observed in acute HIV infection through MRS myo-inositol/creatinine ratio elevations.1

While neuropathy was reported or observed in 17% of our acute HIV participants, another study in untreated primary HIV infection reported neuropathy occurring in as many as 35% of individuals.24 In that study, neuropathy was found to correlate with CSF and plasma markers of immune activation, raising the possibility that immediate treatment may reduce adverse neurologic outcomes.

We identified that higher plasma HIV RNA level at diagnosis was associated with having one or more neurologic findings, supporting a relationship with systemic disease severity and neurologic outcomes. However, these participants experienced a similar clinical severity in terms of number of ARS symptoms, and no differences in plasma or CSF markers of macrophage activation, although the assessments of CSF markers were limited by sample size. A separate study in primary HIV observed that CSF HIV RNA, as opposed to plasma HIV RNA, was elevated in those with neurologic symptoms compared to those without.25 In that study, participants had no systematic neurologic evaluation, and had a high rate of severe sequelae requiring hospitalization.

Neurologic findings in acute HIV may not require direct CNS viral involvement, as 4 of our participants experienced CNS-referable neurologic findings despite undetectable CSF HIV RNA at diagnosis. It is possible that our participants have a discrepancy in the presence of HIV RNA in the CSF vs that in the brain parenchyma, an inherent sampling limitation when CSF is used to infer brain involvement. Similar incongruity has been described in macaque models of early HIV.26 However, the presence of CNS-referable symptoms in participants without detectable CSF HIV RNA may imply an indirect role of systemic immune activation or inflammation, although we did not observe group differences in a plasma marker of macrophage activation. A study in patients with myasthenia gravis, a disease of immune activation without CNS antibody expression, similarly found cognitive deficits compared to controls that were unrelated to the participant's mood or medication.27 Relatedly, the observed case of GBS may not have been caused by direct HIV-related factors, but instead by immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome, as has been reported in primary HIV.28

All participants received cART upon study entry; thus our study lacks the untreated arm needed to demonstrate how early cART intervention influences the trajectory of neurologic findings in acute HIV. Consequently, we report only concurrent changes without attributing causality. Additionally, the lack of comparative neurologic findings in uninfected control participants limits the ability to determine what is driven by HIV infection, vs baseline incidence in this population. The decreased frequency of findings concurrent with cART initiation supports the notion that these findings are related to HIV infection. It is also possible that the early cluster of findings at diagnosis instead resulted from a natural virologic progression of HIV infection, and is independent of treatment. Interestingly, while early treatment is presumed to be neuroprotective, a study of patients with primary HIV showed compromised microstructural and macromolecular neuroimaging changes in the anterior corpus callosum, as well as increased CSF percent, in those starting treatment in the first year compared to untreated controls also in primary HIV.29

There was illicit drug use in this population, possibly confounding our neurologic findings, although the pattern of use was principally sporadic amyl nitrite use (poppers) during sexual encounters.30 Given the homogeneity of participants in terms of HIV-1 clade CRF01-AE, our findings may not generalize to other clades. Additional study limitations include the restricted demographics of the participants.

Individuals diagnosed and treated during acute HIV infection commonly have mild neurologic findings, but a low frequency of fulminant neurologic issues, in the first 3 months after diagnosis. The mild neurologic findings include cognitive complaints, motor findings, and neuropathy, and tend to remit concurrent with treatment.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank the study participants and staff from the Thai Red Cross AIDS Research Centre, the Silom Community Clinic in Bangkok, and the Early Capture HIV Cohort (ECHO) Center in Pattaya, Thailand, for contributions to this study. SEARCH is a research collaboration among the Thai Red Cross AIDS Research Centre (TRCARC), the University of California San Francisco, the University of Hawaii, and the Department of Retrovirology, US Army Medical Component, Armed Forces Research Institute of Medical Sciences (USAMC-AFRIMS).

GLOSSARY

- ARS

acute retroviral syndrome

- cART

combination antiretroviral therapy

- cART+

combination antiretroviral therapy regimen augmented with antiretrovirals maraviroc and raltegravir

- EIA

enzyme immunoassay

- FLAIR

fluid-attenuated inversion recovery

- GBS

Guillain-Barré syndrome

- HADS

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

- HADS-A

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale anxiety subscore

- HADS-D

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale depression subscore

- MRS

magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- UPDRS

Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale

Footnotes

Editorial, page 126

Supplemental data at Neurology.org

Contributor Information

Collaborators: SEARCH 010/RV254 Study Group, Praphan Phanuphak, Nittaya Phanuphak, Donn Colby, Thep Chalermchai, Nitiya Chomchey, Duanghathai Suttichom, Somprartthana Rattanamanee, Puttachard Sangtawan, Somprartthana Rattanamanee, Bessara Nuntapinit, Phiromrat Rakyat, Surasit Inprakong, Sukanya Lucksanawong, Panjaree Ruangjan, Anake Nuchwong, Panadda Kruacharoen, Robert O’Connell, Collin Adams, Katherine Clifford, Lauren Wendelken, Leah Le, Hetal Mistry, Sodsai Tovanabutra, Suteeraporn Pinyakorn, Merlin Robb, and Robert Paul

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Joanna Hellmuth codesigned the study, performed statistical analyses, and wrote the manuscript. James Fletcher, Eugene Kroon, Jintana Intasan, Peeriya Prueksakaew, Suwanna Puttamaswin, and Nittaya Phanuphak contributed to acquisition and interpretation of clinical data, as well as manuscript review. Sukalaya Lerdlum, Mantana Pothisri, and Jared Narvid contributed to processing and interpretation of MRI data, as well as manuscript review. Linda Jagodzinski, Shelly J. Krebs, and Bonnie Slike contributed to processing and analysis of the soluble biomarkers, as well as manuscript review. Isabel Allen assisted with statistical analyses and manuscript revision. Victor Valcour, Jintanat Ananworanich, and Serena Spudich codesigned the study, contributed to interpretation of the data, and revised the manuscript.

STUDY FUNDING

Supported by NIH/NIMH grants R01MH095613, R01NS061696, and R21MH086341, as well as the US Military HIV Research Program, with added support from the National Institutes of Mental Health. The following organizations provided antiretroviral therapy: tenofovir, lamivudine, efavirenz from the Thai Government Pharmaceutical Organization; emtricitabine/tenofovir (Truvada) and emtricitabine/tenofovir/efavirenz (Sustiva) from Gilead (Foster City, CA); efavirenz (Sustiva) and raltegravir (Isentress) from Merck (San Francisco, CA); and maraviroc (Selzentry) from ViiV Healthcare (Middlesex, UK). The funders had no role in the design of this study, data collection or analysis, the preparation of the manuscript, or decision to publish.

DISCLOSURE

J. Hellmuth and J. Fletcher report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. V. Valcour has served as a consultant for ViiV Healthcare on topics unrelated to the work presented here. E. Kroon reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. J. Ananworanich has received honorarium from ViiV Healthcare, Merck, and Roche for her participation in advisory meetings. J. Intasan, S. Lerdlum, J. Narvid, M. Pothisri, I. Allen, S. Krebs, B. Slike, P. Prueksakaew, L. Jagodzinski, S. Puttamaswin, N. Phanuphak, and S. Spudich report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Valcour V, Chalermchai T, Sailasuta N, et al. . Central nervous system viral invasion and inflammation during acute HIV infection. J Infect Dis 2012;206:275–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krasner CG, Cohen SH. Bilateral Bell's palsy and aseptic meningitis in a patient with acute human immunodeficiency virus seroconversion. West J Med 1993;159:604–605. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Serrano P, Hernandez N, Arroyo JA, de Llobet JM, Domingo P. Bilateral Bell's palsy and acute HIV type 1 infection: report of 2 cases and review. Clin Infect Dis 2007;44:e57–e61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hagberg L, Malmvall BE, Svennerholm L, Alestig K, Norkrans G. Guillain-Barre syndrome as an early manifestation of HIV central nervous system infection. Scand J Infect Dis 1986;18:591–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Larsen M, Toft PB, Bernhard P, Herning M. Bilateral optic neuritis in acute human immunodeficiency virus infection. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 1998;76:737–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carne CA, Tedder RS, Smith A, et al. . Acute encephalopathy coincident with seroconversion for anti-HTLV-III. Lancet 1985;2:1206–1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Douvoyiannis M, Litman N. Acute encephalopathy and multi-organ involvement with rhabdomyolysis during primary HIV. Int J Infect Dis 2009;13:e299–e304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Denning DW, Anderson J, Rudge P, Smith H. Acute myelopathy associated with primary infection with human immunodeficiency virus. Br Med J 1987;294:143–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Narciso P, Galgani S, Del Grosso B, et al. . Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis as manifestation of primary HIV infection. Neurology 2001;57:1493–1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mogensen TH, Marinovskij E, Larsen CS. Acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis (ADEM) as initial presentation of primary HIV infection. Scand J Infect Dis 2007;39:630–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Braun DL, Kouyos RD, Balmer B, Grube C, Weber R, Gunthard HF. Frequency and spectrum of unexpected clinical manifestations of primary HIV-1 infection. Clin Infect Dis 2015;61:1013–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Souza MS, Phanuphak N, Pinyakorn S, et al. . Impact of nucleic acid testing relative to antigen/antibody combination immunoassay on the detection of acute HIV infection. AIDS 2015;29:793–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fiebig EW, Wright DJ, Rawal BD, et al. . Dynamics of HIV viremia and antibody seroconversion in plasma donors: implications for diagnosis and staging of primary HIV infection. AIDS 2003;17:1871–1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nuesch R, Gayet-Ageron A, Chetchotisakd P, et al. . The impact of combination antiretroviral therapy and its interruption on anxiety, stress, depression and quality of life in Thai patients. Open AIDS J 2009;15:38–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Letendre S, FitzSimons C, Ellis RJ, et al. . Correlates of CSF viral loads in 1221 volunteers of the CHARTER cohort. Presented at the 17th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, February 16–19, 2010, San Francisco, CA.

- 17.Price RW, Yiannoutsos CT, Clifford DB, et al. . Neurological outcomes in late HIV infection: adverse impact of neurological impairment on survival and protective effect of antiviral therapy. AIDS 1999;13:1677–1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kore I, Ananworanich J, Valcour V, et al. . Neuropsychological impairment in acute HIV and the effect of immediate antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015;70:393–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heaps J, Valcour V, Chalermchai T, et al. . Development of normative neuropsychological performance in Thailand for the assessment of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2013;35:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moore DJ, Letendre SL, Morris S, et al. . Neurocognitive functioning in acute or early HIV infection. J Neurovirol 2011;17:50–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hersh B, Rajendran PR, Battinelli D. Parkinsonism as the presenting manifestation of HIV infection: improvement on HAART. Neurology 2001;56:278–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tisch S, Brew B. Parkinsonism in HIV-infected patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy. Neurology 2009;73:401–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Witt ST, Laird AR, Meyerand ME. Functional neuroimaging correlates of finger-tapping task variations: an ALE meta-analysis. Neuroimage 2008;42:343–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang SX, Ho EL, Grill M, et al. . Peripheral neuropathy in primary HIV infection associates with systemic and central nervous system immune activation. JAIDS 2014;66:303–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tambussi G, Gori A, Capiluppi B, et al. . Neurological symptoms during primary human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection correlate with high levels of HIV RNA in cerebrospinal fluid. Clin Infect Dis 2000;30:962–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clements JE, Babas T, Mankowski JL, et al. . The central nervous system as a reservoir for simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV): steady-state levels of SIV DNA in brain from acute through asymptomatic infection. J Infect Dis 2002;186:905–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paul RH, Cohen RA, Gilchrist JM. Ratings of subjective mental fatigue relate to cognitive performance in patients with myasthenia gravis. J Clin Neurosci 2002;9:243–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Teo EC, Azwra A, Jones RL, Gazzard BG, Nelson M. Guillain-Barre syndrome following immune reconstitution after antiretroviral therapy for primary HIV infection. J HIV Ther 2007;12:62–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kelly SG, Taiwo BO, Wu Y, et al. . Early suppressive antiretroviral therapy in HIV infection is associated with measurable changes in the corpus callosum. J Neurovirol 2014;20:514–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen X, Li X, Zheng J, et al. . Club drugs and HIV/STD infection: an exploratory analysis among men who have sex with men in Changsha, China. PLoS One 2015;10:e0126320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.