Abstract

Angiotensin type 1 receptor blockers (ARBs) have been shown to be neuroprotective and neurorestorative in experimental stroke. The mechanisms proposed include anti-inflammatory, antiapoptotic effects, as well as stimulation of endogenous trophic factors leading to angiogenesis and neuroplasticity. We aimed to investigate the involvement of the neurotrophin, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), in ARB-mediated functional recovery after stroke. To achieve this aim, Wistar rats received bilateral intracerebroventricular (ICV) injections of short hairpin RNA (shRNA) lentiviral particles or non-targeting control (NTC) vector, to knock down BDNF in both hemispheres. After 14 days, rats were subjected to 90-minute middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) and received the ARB, candesartan, 1 mg/kg, or saline IV at reperfusion (one dose), then followed for another 14 days using a battery of behavioral tests. BDNF protein expression was successfully reduced by about 70% in both hemispheres at 14 days after bilateral shRNA lentiviral particles injection. The NTC group that received candesartan showed better functional outcome as well as increased vascular density and synaptogenesis as compared to saline treatment. BDNF knockdown abrogated the beneficial effects of candesartan on neurobehavioral outcome, vascular density and synaptogenesis. In conclusion, BDNF is directly involved in candesartan-mediated functional recovery, angiogenesis and synaptogenesis.

Keywords: Stroke, angiotensin type 1 receptor blockade, behavioral recovery, angiogenesis, brain derived neurotrophic factor

Introduction

Angiotensin type 1-receptor blockers (ARBs) have been shown to reduce neurovascular injury and improve recovery after experimental ischemic stroke.[1-4] The underlying mechanisms are multifaceted and include normalizing cerebral blood flow,[2] restoring endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) activity, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic effects, as well as stimulation of pro-angiogenic trophic factors.[1,5-10] Data from our lab demonstrated that the pro-recovery effect induced by a single dose of candesartan was maintained for 7 days after stroke. This was accompanied by a pro-angiogenic state in both stroked and normal animals.[8] Additionally, we have shown that candesartan treatment was associated with upregulation of brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in rat brain after stroke, and in cultured human brain endothelial cells.[11-13]

BDNF is a member of the neurotrophin family that can exert neuroprotective, neuroplastic, neurogenic, and angiogenic effects thus leading to recovery after CNS insults.[14,15] Lower serum BDNF levels have been associated with increased risk of stroke in humans.[16] Experimentally, BDNF has been shown to be involved in angiogenesis, synaptogenesis and functional recovery after stroke.[17-19] ICV injection of collagen-binding BDNF promoted angiogenesis, reduced cell apoptosis, and improved functional recovery after MCAO in rats.[20] Similarly, brain transplantation of human neural stem cells overexpressing BDNF has been shown to stimulate brain angiogenesis and promote functional recovery in a mouse intracerebral hemorrhage model.[21] Synaptophysin is a synaptic protein that is expressed during synapse formation, and therefore considered as a marker of synaptogenesis.[22] Synaptophysin upregulation after experimental stroke coincided with BDNF expression. Moreover, post-stroke IV administration of BDNF increased synaptophysin expression and enhanced motor recovery in rats.[18]

Our work and others have documented the increased expression of BDNF and its receptor, TrkB, with ARB treatment after experimental CNS disorders including stroke.[13,23-25] Specifically, studies by Krikov et al. and Ishrat et al. demonstrated an increase in BDNF and TrkB expression with candesartan treatment after experimental stroke.[23,13] While this suggests an association between candesartan-mediated functional recovery and BDNF/TrkB system, a causal relationship is not yet established. Additionally, we have previously shown that BDNF is directly involved in the pro-angiogenic effect of candesartan on human brain microvascular endothelial cells but this was done only in vitro.[11] Therefore, it is still not clear whether BDNF is directly involved in the candesartan-mediated pro-angiogenic state and functional recovery after experimental ischemic stroke in vivo. To test this, we knocked down BDNF in rat brains before stroke induction and candesartan treatment, using short hairpin RNA (shRNA) lentiviral particles. Animals were followed up for 14 days using behavioral tests, then brains were collected for vascular density measurement to determine the involvement of BDNF in candesartan-mediated functional recovery and angiogenesis, respectively, after stroke.

Materials and methods

Animals

All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the Charlie Norwood Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Experiments were performed on 7-8 weeks old, adult male Wistar rats (200-220 grams) that were singly housed with free access to food and water.

In vivo BDNF knockdown

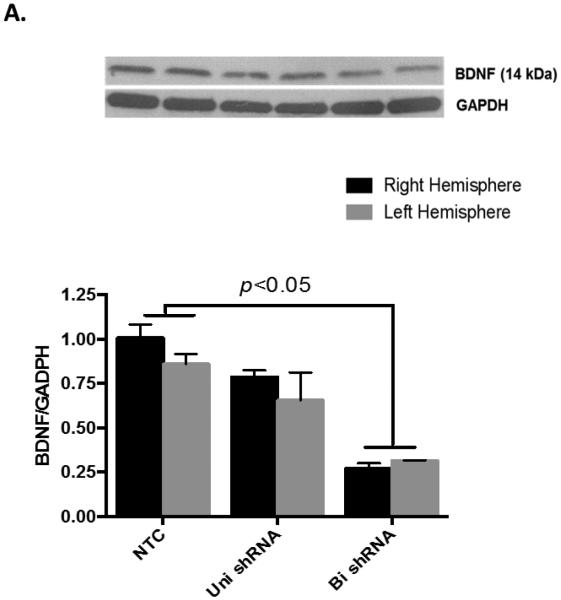

Intracerebroventricular (ICV) injections were conducted using a stereotaxic instrument under isoflurane anesthesia. Stereotaxic coordinates used were −1 mm anteroposterior, 2 mm lateral and −3 mm dorsoventral relative to bregma. 5 μl of lentiviral BDNF shRNA (SMARTchoice lentiviral rat Bdnf hCMV-TurboGFP shRNA, 1 × 108 TU/mL, Dharmacon, # SH0800460210) or non-targeting control vector (NTC) were slowly injected over 5 minutes into each of the lateral ventricles. Animals were then kept for 14 days to allow for recovery, and viral particle integration into their genome, shRNA expression and BDNF knockdown. The first set of animals was sacrificed at 14 days to test the degree of knockdown (Fig 1A), and a second set was subjected to MCAO then followed up for another 14 days as described below (Fig 1B).

Figure 1. Intracerebroventricular delivery of BDNF shRNA expressing lentiviral particles inhibits BDNF expression.

A) BDNF shRNA expressing lentiviruses were injected into the lateral ventricles of Wistar rats and animals were sacrificed after 14 days. Uni- and bi- lateral ICV injection achieved about 30% and 70% reduction in BDNF protein levels, respectively, as assessed by Western blotting. n=3 per group. (B) Schematic diagram of the study: animals were subjected to 90 min-MCAO after 14 days of bilateral ICV injection and randomized to IV candesartan (1 mg/kg) or saline at reperfusion.

Cerebral ischemia

14 days after the ICV injection, rats (9-10 weeks old – 280-320 grams) were subjected to 90-minute middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) as described previously.[26] At the time of reperfusion, animals were randomized to receive either candesartan (1 mg/kg) or saline intravenously (IV). Rats were followed up for another 14 days using neurobehavioral tests and then were euthanized at day 14 post-stroke as previously described.[4,8,9] Brains were harvested and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight, transferred to 30% sucrose, then cut into frozen sections using a microtome.

Behavioral outcome analysis

Functional outcome was evaluated by a blinded investigator using a battery of behavioral tests on days 1, 4, 7, 10, and 14 after MCAO:

Modified Bederson test: Rats were given a score from 0 to 4 based on their behavior in an open field. Beam walk test: Rats’ balance on a horizontal beam was observed and scored from 0 to 6. Paw grasp test: Rats were held by tail, allowed to grasp a vertical pole and scored from 1 to 3. In these three tests, higher score denotes worse outcome. Detailed description of the tests was provided previously.[26] Grid walking test: Rats were placed on a grid composed of 3.8×3.8 cm cells, elevated 1 m above the floor. A camera was placed at a 45° angle below the grid to videotape animal movement for 5 minutes. Two blinded investigators counted the number of forelimb fault steps in addition to the total number of steps. Results were presented as % faulty steps.

Immunohistochemistry

Sections were processed simultaneously as described previously.[27] Primary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4°C at the following dilutions: rabbit anti-laminin (1/50; DakoCytomation), anti-synaptophysin (1/50; Abcam), anti-VEGF (1/200; Millipore), anti-NeuN (1/200; Millipore), and anti-GFAP (1/300; Sigma), followed by fluorescent secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. Negative controls were prepared by omitting the primary antibodies. Laminin-stained vascular profiles and VEGF immunofluorescence were quantified using ImageJ software (NIH) in 5 different fields per section digitized from the ischemic border zone using a 20X objective lens. Similarly, synaptophysin was quantified in 4 different fields from both hemispheres using ImageJ software (NIH). Images were taken using Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope.

Western Blot Analysis

To confirm BDNF knockdown, brains (whole cerebral hemispheres) collected 14 days after ICV injection were separated into left and right sides then homogenized and run on SDS-PAGE as described previously,[9] transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and probed with anti-BDNF antibody (Santa Cruz). Band optical densities were quantified using ImageJ software (NIH), and divided by the respective loading control (GAPDH) band, then normalized to the right control hemisphere to facilitate the visual comparison of the magnitude of BDNF knockdown from control.

Statistical analysis

Two-way repeated measure ANOVA was conducted for the behavioral data analysis using SAS 9.4. Post hoc pair-wise comparisons between groups over time were performed using a Bonferroni adjustment to the overall alpha level. Differences between groups in immunostaining experiments were examined using two-way ANOVA test followed by Tukey post hoc analysis using GraphPad prism software (5.1). Statistical significance was assessed at an alpha level of 0.05. Results are presented as mean ± SEM.

Results

Short hairpin RNA knocks down BDNF gene expression in a dose-dependent manner

We aimed to knock down BDNF in the brain immediately before induction of stroke to assess its involvement in candesartan’s effect on stroke outcome. To achieve this, we determined the efficiency of unilateral and bilateral intracerebroventricular (ICV) injection of lentiviruses expressing BDNF shRNA. While unilateral injection achieved only 30% knockdown of BDNF protein, bilateral injection successfully knocked down BDNF expression by about 70% after 14 days as assessed by Western blotting (Fig 1A). Therefore, we used bilateral ICV injection for the following experiments. Animals with BDNF knockdown did not show differences in weight gain or motor performance compared to those treated with non-targeting control (NTC) vector. Similarly, weight change after stroke was not affected by BDNF knockdown (data not shown). As shown in the schematic diagram (Fig 1B), animals were subjected to 90 min-MCAO after 14 days of bilateral ICV injection and randomized to candesartan (1 mg/kg) or saline at reperfusion. This 2X2 study design resulted in 4 treatment groups: BDNF knockdown rats treated with candesartan or saline (cand/KD or sal/KD) and control rats that received NTC vector then candesartan or saline (cand/NTC or sal/NTC).

Single dose candesartan administration leads to BDNF-dependent long-term functional improvement after stroke

Data from our lab and others have demonstrated the pro-recovery effect of ARBs treatment on stroke outcome.[4,8,28,2] As previously published,[8] a single dose of candesartan successfully achieved long-term functional improvement up to 14 days after stroke. This improvement was evident as early as day 1 after stroke and was consistently observed in different functional tests in the cand+NTC group as compared to sal+NTC (Fig 2). Candesartan has been shown to increase BDNF expression,[9] which is known to play a vital role in functional recovery after stroke.[19,29,18,30,17] Knocking down BDNF abrogated the candesartan-induced functional improvement (Fig 2). The effect of knocking down BDNF on functional outcome was observed immediately after stroke and maintained during the whole period of follow up. However, BDNF knockdown did not further worsen the stroke outcome in the saline-treated animals.

Figure 2. AT1 blockade induced pro-recovery effect is BDNF-dependent.

Candesartan induced improvement in stroke outcome as assessed using modified Bederson score (A), beam walk test (B), paw grasp test (C), and grid walking test (D). BDNF knockdown abrogated the pro-recovery effect of candesartan. Letter ‘a’ denotes that cand/NTC group is significantly different from cand/KD and sal/NTC groups. Letter ‘b’ denotes that cand/NTC is significantly different from cand/KD. Letter ‘c’ denotes that cand/NTC group is significantly different from sal/NTC at the respective time points. Data is presented as mean±SEM; n=6-8 per group.

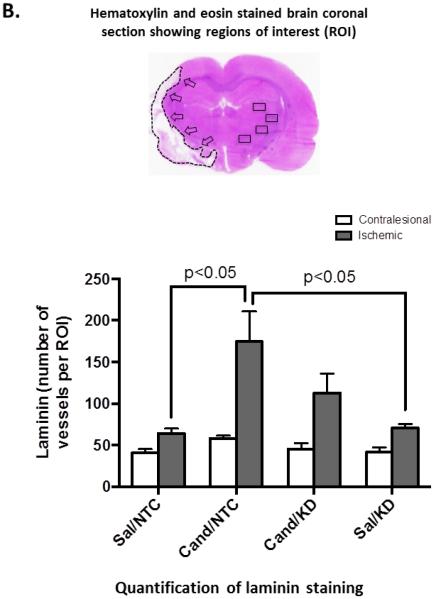

Candesartan induces a BDNF-dependent pro-angiogenic response in the brain

We have previously demonstrated the ability of candesartan to induce a robust pro-angiogenic response in the brain after experimental stroke.[8] BDNF is a well-established angiogenic factor and was found to mediate a large part of candesartan-induced angiogenesis in vitro.[11] Here we assessed the role of BDNF in candesartan-induced angiogenesis after stroke in vivo. As expected, a single dose of candesartan induced a robust increase in vascular density in the ischemic border zone at 14 days after stroke (cand/NTC vs sal/NTC). BDNF Knockdown rats treated with candesartan (cand/KD) showed less angiogenic response that did not reach statistical significance (Fig 3A).

Figure 3. AT1 blockade increases brain vascular density in the ischemic border zone at 14 days after stroke.

Representative images (A) and quantification (B) of vascular density in the ischemic border zone as measured by laminin staining. Candesartan treatment induced a BDNF-dependent increase in vascular density. Data is presented as mean±SEM; n=5-7 per group.

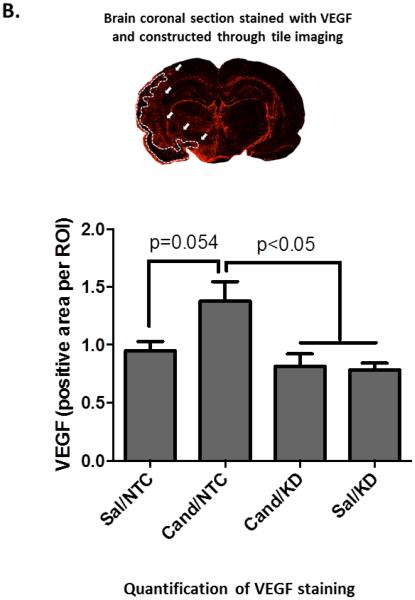

Candesartan regulates VEGF expression in a BDNF-dependent manner

We have previously demonstrated the ability of candesartan to increase VEGF expression after stroke.[8,9] In addition, VEGF expression has been shown to be regulated by BDNF. [31,32] It is still unknown whether BDNF regulates VEGF expression in the brain after stroke. Astrocytes and neurons are major sources of VEGF after stroke.[33-35] At the ischemic border zone, VEGF expression strongly co-localized with reactive astrocytes, including astrocyte end-feet surrounding blood vessels. In addition, VEGF was co-localized with neurons but to a lesser extent. Consistent with our previous data, candesartan treatment showed a strong trend towards increased VEGF immunoreactivity in brain sections as compared to saline (cand/NTC vs sal/NTC, p=0.054 – two-way ANOVA). BDNF knockdown blunted candesartan-induced VEGF expression suggesting a link between BDNF and VEGF upregulation (Fig 3B). BDNF knockdown did not affect the basal VEGF expression in saline treated animals.

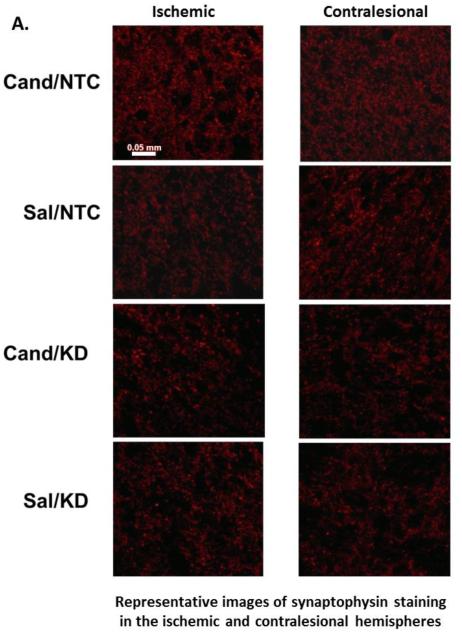

Candesartan induces a BDNF-dependent synaptogenesis in the brain

Candesartan has been shown to enhance synaptogenesis after experimental stroke.[36] Moreover, the contralesional hemisphere has been shown to actively remodel after stroke,[37] and angiotensin modulation increases this response.[9,26] Candesartan administration increased synaptophysin expression in both hemispheres as compared to saline (cand/NTC vs sal/NTC). Candesartan treatment in BDNF knockdown rats did not achieve similar increase in synaptogenesis (Fig 4).

Figure 4. AT1 blockade increases VEGF expression in the ischemic border zone at 14 days after stroke.

Representative images (A) and quantification (B) of VEGF expression in the ischemic border zone. Candesartan treatment induced a BDNF-dependent increase in VEGF expression in the ischemic border zone. VEGF expression strongly co-localized with the astrocyte marker, GFAP, including astrocyte end-feet surrounding blood vessels at the ischemic border zone (marked by arrows) (A). VEGF expression also co-localized, to a lesser extent, with and around the neuronal marker, NeuN (marked by arrows – images taken from the ischemic hemisphere of a rat treated with cand/NTC) (C). Data is presented as mean±SEM; n=5-7 per group.

Discussion

Our data demonstrates the involvement of BDNF in ARB-mediated long-term recovery after stroke. Additionally, we demonstrated that the candesartan pro-angiogenic effect is BDNF-dependent in vivo. Furthermore, our data supports the ability of candesartan to induce a BDNF-dependent synaptogenesis. Interestingly, BDNF knockdown by itself did not alter endogenous recovery mechanisms after stroke.

Because of its vital role in cardiovascular [38] and central nervous system [39,40] development, homozygous (BDNF −/−) knockout animals have limited survival after birth.[38] Heterozygous (BDNF +/−) or TrkB knockout mice are viable but compensatory mechanisms that may occur during neurodevelopment are unknown. The use of short hairpin RNA (shRNA) lentiviral particles allows the strategic and localized knockdown of target gene expression in vivo.[41] Lentiviral particles are widely used in central nervous system research since they are retroviruses that integrate in host genome and can infect both dividing and non-dividing cells including neurons.[42] Upon integration of lentiviruses into host genome, the carried shRNA is constitutively expressed leading to stable and permanent knockdown of the target gene. As reported previously,[43-46] we have demonstrated the feasibility of using shRNA-expressing lentiviruses to knock down BDNF in the brain shortly before stroke induction to avoid long-term compensatory mechanisms.

Following ischemic CNS insults, recovery requires a harmonized interplay between different components of the neurovascular unit. Madri et al. demonstrated the essential role of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and BDNF in mediating this interplay.[47] Previously, we have demonstrated the ability of AT1 blockade to increase VEGF and BDNF expression after stroke.[9,13,12] This paper was focused on assessing the hypothesis that BDNF is involved in ARB induced recovery after stroke through angiogenesis and neuroplasticity. Therefore, 14 days post-stroke time point was chosen. Our findings demonstrate that AT1 blockade-mediated motor recovery after stroke was blunted with knocking down BDNF. Similarly, AT1 blockade-mediated angiogenesis and neuroplasticity were negated in BDNF knockdown rats. Collectively, these findings suggest that the AT1 blockade induced pro-recovery effect is BDNF-dependent. A limitation of the current study is the lack of earlier time point to examine the role of BDNF in candesartan-mediated protective effects against early events after stroke such as oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis.

Angiogenesis has been shown to play a vital role in recovery after CNS ischemic insults.[48] We have previously shown that AT1R blockade or AT2R stimulation induce a long-term pro-angiogenic response in the rat brain after stroke.[8,9,26,13] Additionally, we demonstrated an indispensable role of BDNF in AT1 blockade induced angiogenesis in human cerebromicrovascular endothelial cells (hCMECs).[11] Our current data demonstrates that this pro-angiogenic effect is BDNF-dependent in vivo as well. In addition to angiogenesis, recent data demonstrated the importance of neuroplastic changes in the contralateral hemisphere in recovery after stroke.[37] BDNF plays a central role in synaptic plasticity and synaptogenesis,[49] and BDNF knockout mice show reduced synaptophysin expression.[50] IV administration of BDNF after stroke increased synaptophysin expression,[18] while blocking BDNF with specific immunoadhesin chimera (TrkB-IgG) abrogated exercise induced-synaptogenesis. Our results demonstrate the ability of AT1 blockade to increase the extent of synaptogenesis in both the ischemic and contralesional hemispheres in a BDNF-dependent manner.

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is a well-studied angiogenic mediator with established neuroprotective effects.[51] In cancer tissues, VEGF expression was found to be regulated by BDNF.[32,31] Additionally, the expression of both proteins was demonstrated to be co-regulated.[47] Our data shows increase in VEGF expression with candesartan in NTC treated animals as compared to those treated with candesartan after BDNF knockdown. This suggests that candesartan-mediated increase in VEGF expression after cerebral ischemia could be, at least, partially mediated through BDNF.

Despite the well-established role of BDNF in recovery after stroke, BDNF knockdown did not worsen stroke outcome in the saline treated animals. Multiple studies have consistently shown that exogenous BDNF administration improve stroke outcome.[18,19,29,52,53] Paradoxically, one study conducted in BDNF(+/−) mice showed enhanced functional recovery after stroke with decreased brain levels of BDNF.[54] Ploughman et al. assessed the role of endogenous BDNF in rehabilitation induced stroke recovery through knocking down BDNF expression using antisense BDNF oligonucleotide infusion. Their data demonstrated an indispensable role of BDNF in rehabilitation induced recovery after stroke. Counterintuitively, knocking down BDNF in animals that did not receive rehabilitation did not worsen recovery as compared to vehicle treated animals, which is consistent with our current findings. Collectively, these findings suggest that while therapeutic interventions that are known to increase BDNF expression such as exercise[55,56] and AT1 blockade,[9,23,13] could be dependent on its brain levels, knocking down endogenous brain BDNF expression by itself may not have an effect on stroke recovery.

In conclusion, AT1 blockade with candesartan after stroke induces a BDNF-dependent functional recovery that is associated with both angiogenesis and increased synaptic plasticity.

Figure 5. AT1 blockade increases synaptophysin expression in both hemispheres at 14 days after stroke.

Representative images (A) and quantification (B) of synaptophysin expression in the ischemic and contralesional hemispheres. Candesartan treatment increased synaptophysin expression in both hemispheres in a BDNF-dependent manner. Data is presented as mean±SEM; n=5-7 per group.

Acknowledgments

Funded by: RO1-NS063965, R21-NS088016, VA Merit Review-BX000891 and Jowdy Professorship to SCF; RO1-NS083559 to AE

References

- 1.Ito T, Yamakawa H, Bregonzio C, Terron JA, Falcon-Neri A, Saavedra JM. Protection against ischemia and improvement of cerebral blood flow in genetically hypertensive rats by chronic pretreatment with an angiotensin II AT1 antagonist. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2002;33(9):2297–2303. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000027274.03779.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Engelhorn T, Goerike S, Doerfler A, Okorn C, Forsting M, Heusch G, Schulz R. The angiotensin II type 1-receptor blocker candesartan increases cerebral blood flow, reduces infarct size, and improves neurologic outcome after transient cerebral ischemia in rats. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism : official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2004;24(4):467–474. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200404000-00012. doi:10.1097/00004647-200404000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Groth W, Blume A, Gohlke P, Unger T, Culman J. Chronic pretreatment with candesartan improves recovery from focal cerebral ischaemia in rats. Journal of hypertension. 2003;21(11):2175–2182. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200311000-00028. doi:10.1097/01.hjh.0000098126.00558.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fagan SC, Kozak A, Hill WD, Pollock DM, Xu L, Johnson MH, Ergul A, Hess DC. Hypertension after experimental cerebral ischemia: candesartan provides neurovascular protection. Journal of hypertension. 2006;24(3):535–539. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000209990.41304.43. doi:10.1097/01.hjh.0000209990.41304.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamai M, Iwai M, Ide A, Tomochika H, Tomono Y, Mogi M, Horiuchi M. Comparison of inhibitory action of candesartan and enalapril on brain ischemia through inhibition of oxidative stress. Neuropharmacology. 2006;51(4):822–828. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.05.029. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamakawa H, Jezova M, Ando H, Saavedra JM. Normalization of endothelial and inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in brain microvessels of spontaneously hypertensive rats by angiotensin II AT1 receptor inhibition. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism : official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2003;23(3):371–380. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000047369.05600.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lou M, Blume A, Zhao Y, Gohlke P, Deuschl G, Herdegen T, Culman J. Sustained blockade of brain AT1 receptors before and after focal cerebral ischemia alleviates neurologic deficits and reduces neuronal injury, apoptosis, and inflammatory responses in the rat. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism : official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2004;24(5):536–547. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200405000-00008. doi:10.1097/00004647-200405000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kozak A, Ergul A, El-Remessy AB, Johnson MH, Machado LS, Elewa HF, Abdelsaid M, Wiley DC, Fagan SC. Candesartan augments ischemia-induced proangiogenic state and results in sustained improvement after stroke. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2009;40(5):1870–1876. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.537225. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.537225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guan W, Somanath PR, Kozak A, Goc A, El-Remessy AB, Ergul A, Johnson MH, Alhusban A, Soliman S, Fagan SC. Vascular protection by angiotensin receptor antagonism involves differential VEGF expression in both hemispheres after experimental stroke. PloS one. 2011;6(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024551. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0024551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ergul A, Abdelsaid M, Fouda AY, Fagan SC. Cerebral neovascularization in diabetes: implications for stroke recovery and beyond. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism : official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2014;34(4):553–563. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.18. doi:10.1038/jcbfm.2014.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alhusban A, Kozak A, Ergul A, Fagan SC. AT1 receptor antagonism is proangiogenic in the brain: BDNF a novel mediator. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 2013;344(2):348–359. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.197483. doi:10.1124/jpet.112.197483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soliman S, Ishrat T, Pillai A, Somanath PR, Ergul A, El-Remessy AB, Fagan SC. Candesartan induces a prolonged proangiogenic effect and augments endothelium-mediated neuroprotection after oxygen and glucose deprivation: role of vascular endothelial growth factors A and B. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 2014;349(3):444–457. doi: 10.1124/jpet.113.212613. doi:10.1124/jpet.113.212613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishrat T, Pillai B, Soliman S, Fouda AY, Kozak A, Johnson MH, Ergul A, Fagan SC. Low-dose candesartan enhances molecular mediators of neuroplasticity and subsequent functional recovery after ischemic stroke in rats. Molecular neurobiology. 2015;51(3):1542–1553. doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-8830-6. doi:10.1007/s12035-014-8830-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagahara AH, Tuszynski MH. Potential therapeutic uses of BDNF in neurological and psychiatric disorders. Nature reviews Drug discovery. 2011;10(3):209–219. doi: 10.1038/nrd3366. doi:10.1038/nrd3366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kermani P, Hempstead B. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor: a newly described mediator of angiogenesis. Trends in cardiovascular medicine. 2007;17(4):140–143. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2007.03.002. doi:10.1016/j.tcm.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pikula A, Beiser AS, Chen TC, Preis SR, Vorgias D, DeCarli C, Au R, Kelly-Hayes M, Kase CS, Wolf PA, Vasan RS, Seshadri S. Serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor and vascular endothelial growth factor levels are associated with risk of stroke and vascular brain injury: Framingham Study. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2013;44(10):2768–2775. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001447. doi:10.1161/strokeaha.113.001447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ploughman M, Windle V, MacLellan CL, White N, Dore JJ, Corbett D. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor contributes to recovery of skilled reaching after focal ischemia in rats. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2009;40(4):1490–1495. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.531806. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.531806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schabitz WR, Berger C, Kollmar R, Seitz M, Tanay E, Kiessling M, Schwab S, Sommer C. Effect of brain-derived neurotrophic factor treatment and forced arm use on functional motor recovery after small cortical ischemia. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2004;35(4):992–997. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000119754.85848.0D. doi:10.1161/01.str.0000119754.85848.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schabitz WR, Steigleder T, Cooper-Kuhn CM, Schwab S, Sommer C, Schneider A, Kuhn HG. Intravenous brain-derived neurotrophic factor enhances poststroke sensorimotor recovery and stimulates neurogenesis. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2007;38(7):2165–2172. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.477331. doi:10.1161/strokeaha.106.477331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guan J, Tong W, Ding W, Du S, Xiao Z, Han Q, Zhu Z, Bao X, Shi X, Wu C, Cao J, Yang Y, Ma W, Li G, Yao Y, Gao J, Wei J, Dai J, Wang R. Neuronal regeneration and protection by collagen-binding BDNF in the rat middle cerebral artery occlusion model. Biomaterials. 2012;33(5):1386–1395. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.10.073. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.10.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee HJ, Lim IJ, Lee MC, Kim SU. Human neural stem cells genetically modified to overexpress brain-derived neurotrophic factor promote functional recovery and neuroprotection in a mouse stroke model. Journal of neuroscience research. 2010;88(15):3282–3294. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22474. doi:10.1002/jnr.22474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fletcher TL, Cameron P, De Camilli P, Banker G. The distribution of synapsin I and synaptophysin in hippocampal neurons developing in culture. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1991;11(6):1617–1626. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-06-01617.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krikov M, Thone-Reineke C, Muller S, Villringer A, Unger T. Candesartan but not ramipril pretreatment improves outcome after stroke and stimulates neurotrophin BNDF/TrkB system in rats. Journal of hypertension. 2008;26(3):544–552. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3282f2dac9. doi:10.1097/HJH.0b013e3282f2dac9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kishi T, Hirooka Y, Sunagawa K. Telmisartan protects against cognitive decline via up-regulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor/tropomyosin-related kinase B in hippocampus of hypertensive rats. Journal of cardiology. 2012;60(6):489–494. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2012.08.004. doi:10.1016/j.jjcc.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sathiya S, Ranju V, Kalaivani P, Priya RJ, Sumathy H, Sunil AG, Babu CS. Telmisartan attenuates MPTP induced dopaminergic degeneration and motor dysfunction through regulation of alpha-synuclein and neurotrophic factors (BDNF and GDNF) expression in C57BL/6J mice. Neuropharmacology. 2013;73:98–110. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.05.025. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alhusban A, Fouda AY, Bindu P, Ishrat T, Soliman S, Fagan SC. Compound 21 is pro-angiogenic in the brain and results in sustained recovery after ischemic stroke. Journal of hypertension. 2015;33(1):170–180. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000364. doi:10.1097/hjh.0000000000000364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fouda A, Kozak A, Alhusban A, Switzer J, Fagan S. Anti-inflammatory IL-10 is upregulated in both hemispheres after experimental ischemic stroke: Hypertension blunts the response. Experimental & Translational Stroke Medicine. 2013;5(1) doi: 10.1186/2040-7378-5-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Randomised trial of a perindopril-based blood-pressure-lowering regimen among 6,105 individuals with previous stroke or transient ischaemic attack. Lancet. 2001;358(9287):1033–1041. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06178-5. doi:S0140-6736(01)06178-5 [pii] 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06178-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muller HD, Hanumanthiah KM, Diederich K, Schwab S, Schabitz WR, Sommer C. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor but not forced arm use improves long-term outcome after photothrombotic stroke and transiently upregulates binding densities of excitatory glutamate receptors in the rat brain. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2008;39(3):1012–1021. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.495069. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.495069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mahmood A, Lu D, Chopp M. Intravenous administration of marrow stromal cells (MSCs) increases the expression of growth factors in rat brain after traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2004;21(1):33–39. doi: 10.1089/089771504772695922. doi:10.1089/089771504772695922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang L, Hu Y, Sun CY, Li J, Guo T, Huang J, Chu ZB. Lentiviral shRNA silencing of BDNF inhibits in vivo multiple myeloma growth and angiogenesis via down-regulated stroma-derived VEGF expression in the bone marrow milieu. Cancer Sci. 2010;101(5):1117–1124. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01515.x. doi:10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01515.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang SM, Lin C, Lin HY, Chiu CM, Fang CW, Liao KF, Chen DR, Yeh WL. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor regulates cell motility in human colon cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2015;22(3):455–464. doi: 10.1530/ERC-15-0007. doi:10.1530/ERC-15-0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cobbs CS, Chen J, Greenberg DA, Graham SH. Vascular endothelial growth factor expression in transient focal cerebral ischemia in the rat. Neuroscience letters. 1998;249(2-3):79–82. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00377-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kovacs Z, Ikezaki K, Samoto K, Inamura T, Fukui M. VEGF and flt. Expression time kinetics in rat brain infarct. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 1996;27(10):1865–1872. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.10.1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Margaritescu O, Pirici D, Margaritescu C. VEGF expression in human brain tissue after acute ischemic stroke. Romanian journal of morphology and embryology = Revue roumaine de morphologie et embryologie. 2011;52(4):1283–1292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bai YY, Gao X, Wang YC, Peng XG, Chang D, Zheng S, Li C, Ju S. Image-guided pro-angiogenic therapy in diabetic stroke mouse models using a multi-modal nanoprobe. Theranostics. 2014;4(8):787–797. doi: 10.7150/thno.9525. doi:10.7150/thno.9525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hermann DM, Chopp M. Promoting brain remodelling and plasticity for stroke recovery: therapeutic promise and potential pitfalls of clinical translation. Lancet neurology. 2012;11(4):369–380. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70039-X. doi:10.1016/s1474-4422(12)70039-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Caporali A, Emanueli C. Cardiovascular actions of neurotrophins. Physiol Rev. 2009;89(1):279–308. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00007.2008. doi:89/1/279 [pii] 10.1152/physrev.00007.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mocchetti I, Brown M. Targeting neurotrophin receptors in the central nervous system. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2008;7(1):71–82. doi: 10.2174/187152708783885138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marini AM, Jiang X, Wu X, Tian F, Zhu D, Okagaki P, Lipsky RH. Role of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and NF-kappaB in neuronal plasticity and survival: From genes to phenotype. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2004;22(2):121–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Singer O, Verma IM. Applications of lentiviral vectors for shRNA delivery and transgenesis. Current gene therapy. 2008;8(6):483–488. doi: 10.2174/156652308786848067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hutson TH, Foster E, Moon LD, Yanez-Munoz RJ. Lentiviral vector-mediated RNA silencing in the central nervous system. Human gene therapy methods. 2014;25(1):14–32. doi: 10.1089/hgtb.2013.016. doi:10.1089/hgtb.2013.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taliaz D, Stall N, Dar DE, Zangen A. Knockdown of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in specific brain sites precipitates behaviors associated with depression and reduces neurogenesis. Molecular psychiatry. 2010;15(1):80–92. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.67. doi:10.1038/mp.2009.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Han JE, Lee EJ, Moon E, Ryu JH, Choi JW, Kim HS. Matrix Metalloproteinase-8 is a Novel Pathogenetic Factor in Focal Cerebral Ischemia. Molecular neurobiology. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-8996-y. doi:10.1007/s12035-014-8996-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang CJ, Qu CQ, Zhang J, Fu PC, Guo SG, Tang RH. Lingo-1 inhibited by RNA interference promotes functional recovery of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Anatomical record (Hoboken, NJ : 2007) 2014;297(12):2356–2363. doi: 10.1002/ar.22988. doi:10.1002/ar.22988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang L, Hong Q, Zhang M, Liu X, Pan XQ, Guo M, Fei L, Guo XR, Tong ML, Chi X. The role of Homer 1a in increasing locomotor activity and non-selective attention, and impairing learning and memory abilities. Brain research. 2013;1515:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.03.030. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2013.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Madri JA. Modeling the neurovascular niche: implications for recovery from CNS injury. Journal of physiology and pharmacology : an official journal of the Polish Physiological Society. 2009;60(Suppl 4):95–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ergul A, Alhusban A, Fagan SC. Angiogenesis: a harmonized target for recovery after stroke. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2012;43(8):2270–2274. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.642710. doi:10.1161/strokeaha.111.642710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Waterhouse EG, Xu B. New insights into the role of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in synaptic plasticity. Molecular and cellular neurosciences. 2009;42(2):81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2009.06.009. doi:10.1016/j.mcn.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pozzo-Miller LD, Gottschalk W, Zhang L, McDermott K, Du J, Gopalakrishnan R, Oho C, Sheng ZH, Lu B. Impairments in high-frequency transmission, synaptic vesicle docking, and synaptic protein distribution in the hippocampus of BDNF knockout mice. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1999;19(12):4972–4983. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-12-04972.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carmeliet P, Jain RK. Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications of angiogenesis. Nature. 2011;473(7347):298–307. doi: 10.1038/nature10144. doi:10.1038/nature10144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yu SJ, Tseng KY, Shen H, Harvey BK, Airavaara M, Wang Y. Local administration of AAV-BDNF to subventricular zone induces functional recovery in stroke rats. PloS one. 2013;8(12):e81750. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081750. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0081750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang Y, Pardridge WM. Blood-brain barrier targeting of BDNF improves motor function in rats with middle cerebral artery occlusion. Brain research. 2006;1111(1):227–229. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.07.005. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nygren J, Kokaia M, Wieloch T. Decreased expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in BDNF(+/−) mice is associated with enhanced recovery of motor performance and increased neuroblast number following experimental stroke. Journal of neuroscience research. 2006;84(3):626–631. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20956. doi:10.1002/jnr.20956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vaynman S, Ying Z, Gomez-Pinilla F. Exercise induces BDNF and synapsin I to specific hippocampal subfields. Journal of neuroscience research. 2004;76(3):356–362. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20077. doi:10.1002/jnr.20077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vaynman SS, Ying Z, Yin D, Gomez-Pinilla F. Exercise differentially regulates synaptic proteins associated to the function of BDNF. Brain research. 2006;1070(1):124–130. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.11.062. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2005.11.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]