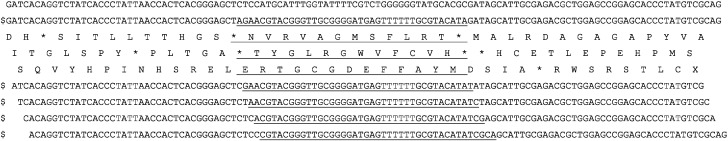

Fig. 1.

Example of running windows reduced to 120 nucleotides for illustration purposes, for the human mitochondrial genome, and swinger transformation of the mid-third 40 nucleotides. First row: regular genomic sequence; rows starting by $ are the first 5 running windows, with the mid third swinger transformed according to swinger rule A ↔ C + G ↔ T (as an example). Running windows used for actual analyses are 270 nucleotides long, and transformed according to each of the 23 swinger transformations, along the same principles as shown above for 120 nucleotides. The three peptides translated from the first running window sequence are also indicated, stops codons are translated here as ‘*’. Analyses searching for mass spectrometry data matching these predicted peptides consider the possibility that any amino acid is integrated at stops (19 possibilities, merging leucine and isoleucine, which are undistinguishable by the sequencing technique used here, because their molecular weights are identical). This means that for a single running window sequence after a single swinger transformation, 3 × 19 = 57 hypothetical peptides are considered. This number is doubled to 114 considering the inverse complement sequence, and multiplied by 23 considering all 23 potential swinger transformations. Hence 2622 peptides are translated from the 23 swinger transformations of each running window sequence indicated by $. This running window structure enables detection of chimeric peptides where the regular part is translated from the 5′, as well as from the 3′ side of the swinger part.