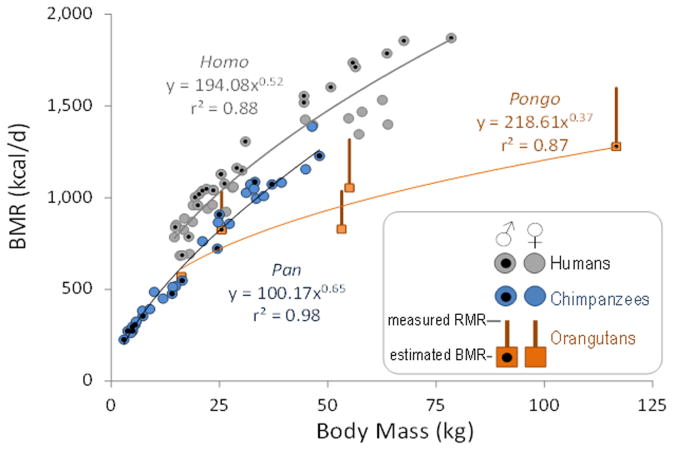

Extended Data Figure 2. BMRs for humans, chimpanzees and orangutans.

Available BMR data for chimpanzees15,16 are primarily from juveniles (age: 2 months to 15 years), and are shown here against comparably aged humans14 (3–18 years). Humans have greater BMRs than chimpanzees in a general linear model of ln-transformed BMR and mass controlling for age and sex (P < 0.001; Supplementary Table 3). Note that in humans (but not chimpanzees), males have greater BMRs for a given body mass, reflecting their greater proportion of FFM (that is, lower body fat percentage). The available data for orangutan BMR consists of one juvenile individual16 (no age reported, mass 16.2 kg). Resting metabolic rates (RMRs; kcal day−1), measured in alert orangutans while sitting17, are also shown. The top of the bar indicates the measured RMR for those individuals, and the bottom square indicates estimated BMR bas ed on those measurements17, assuming BMR = 0.8RMR. No BMR data are available for gorillas. Symbols marked with black circles are males. Allometric regressions shown for Pan (y = 100.17x0.65) and Pongo (y = 218.61x0.37) and were used to estimate BMR for the adult cohorts in Table 1. Human BMR in Table 1 was estimated from published, sex-specific predictive equations for adults27.