Abstract

Brain iron accumulates in several neurodegenerative diseases and can cause oxidative damage, but mechanisms of brain iron homeostasis are incompletely understood. Patients with mutations in the cellular iron-exporting ferroxidase ceruloplasmin (Cp) have brain iron accumulation causing neurodegeneration. Here, we assessed the brains of mice with combined mutation of Cp and its homolog hephaestin. Compared to single mutants, brain iron accumulation was accelerated in double mutants in the cerebellum, substantia nigra, and hippocampus. Iron accumulated within glia, while neurons were iron deficient. There was loss of both neurons and glia. Mice developed ataxia and tremor, and most died by 9 months. Treatment with the oral iron chelator deferiprone diminished brain iron levels, protected against neuron loss, and extended lifespan. Ferroxidases play important, partially overlapping roles in brain iron homeostasis by facilitating iron export from glia, making iron available to neurons.

Keywords: Neurodegeneration, Oxidative Stress, Deferiprone, Iron, Glia, Ceruloplasmin/Hephaestin

Introduction

Dysregulation of iron homeostasis and oxidative stress have been implicated in age-related neurodegenerative diseases including Parkinson’s and age-related macular degeneration (AMD). Due to its high metabolic rate, high content of polyunsaturated fatty acids, and presence of redox-active metals, the brain is susceptible to oxidative damage. Potential oxidative damage is mitigated by multi-copper ferroxidase ceruloplasmin (Cp), which oxidizes iron from its ferrous to the less toxic ferric form. Serum Cp is primarily synthesized in hepatocytes and secreted as a holoprotein. Cp is also located on the surface of astrocytes in the brain, where it plays a major role in the export of iron (Klomp and Gitlin, 1996, Patel and David, 1997, Hellman et al., 2002, Jeong and David, 2003, Kono et al., 2010). By oxidizing ferrous iron, Cp facilitates the binding of ferric iron to transferrin, enabling iron transport to sites of normal physiological use. Cp can also bind and stabilize the only known cellular iron exporter, ferroportin (Fpn) (De Domenico et al., 2007, Kono et al., 2010).

Patients with the rare autosomal recessive disease aceruloplasminemia have mutations in Cp causing brain and retinal neurodegeneration (Harris et al., 1995). Iron accumulates in the retina, basal ganglia, cerebellum, and cortex. These patients suffer from progressive neurological dysfunction, Parkinson’s-like movement disorder, dystonia, cerebellar ataxia, dysarthria, dementia, and retinal degeneration that can resemble AMD (Klomp and Gitlin, 1996, Okamoto et al., 1996, Ponka, 2004, Dunaief et al., 2005, Wolkow et al., 2011). Global cortical atrophy, basal ganglia degeneration, and retinal pigment epithelial cell degeneration have been demonstrated.

Diminished ceruloplasmin activity and decreased copper levels have been found in substantia nigra of post-mortem Parkinson’s disease brains (Ayton et al., 2013). Since ceruloplasmin activity is copper dependent, these data suggest insufficient delivery of copper to ceruloplasmin may lead to diminished CNS ceruloplasmin activity with consequent iron accumulation.

Cp is expressed in astrocytes; Cp knockout (KO) mice have increased iron in the retina, cerebellum, brainstem, and cervical spinal cord by 16mo. This is accompanied by loss of Purkinje cells in cerebellum by 24mo. Increased expression of iron importer divalent metal transporter 1 (Dmt1) in Purkinje cells suggests low iron levels in these cells. Mice have diminished rotarod performance at 16mo but otherwise no overt motor deficits (Jeong and David, 2006).

Ferroxidase function can also be provided by the Cp homolog, hephaestin (Heph). Heph, fifty percent identical to Cp at the amino-acid level, facilitates intestinal iron absorption (Anderson et al., 2002) and co-localizes with Fpn in human enterocytes (Han and Kim, 2007). Conditional knockout of Heph in enterocytes impairs iron export from enterocytes to the blood stream (Fuqua et al., 2014). Similarly, the sex-linked anemia (sla) mouse has a deletion of the penultimate two exons, resulting in diminished ferroxidase function and protein levels leading to defective small intestine iron transport and iron deficiency anemia (Vulpe et al., 1999). Like Cp, Heph has an extracellular copper-dependent ferroxidase domain. Heph is anchored to the plasma membrane by a transmembrane domain, but, unlike Cp, does not have a secreted form. Heph is expressed in oligodendrocytes and microglia. Hephsla mice have impaired rotarod performance beginning at 9 months (Schulz et al., 2011).

Combined deficiency of Cp and Heph results in iron accumulation in spinal cord white matter oligodendrocytes, some of which express both ferroxidases. Oligodendrocytes in the double-mutant mice have low levels of paranodal protein Caspr and abnormal ultrastructure (Schulz et al., 2011). Similarly, combined Cp and Heph deficiency, but not single mutation in Cp or Heph, results in retinal iron accumulation by 6mo, causing degeneration with features of AMD (Hahn et al., 2004, Hadziahmetovic et al., 2008). Single KO for Cp results in a 15% increase in substantia nigra iron levels at age 5mo (Ayton et al. 2014).

We studied the effect of combined deficiency of Cp and Heph on the brain. We focused on brain regions with marked iron accumulation: cerebellum and substantia nigra, and determined the cellular iron distribution pattern. We also tested the protective activity of deferiprone, an oral iron chelator, FDA-approved for thalassemia syndromes that has also been tested in a proof-of-concept clinical trial for Parkinson’s disease (Devos et al. 2014).

Materials and Methods

Reagents and animals

Chemical and biological kits were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) unless stated otherwise. The multi-copper oxidase mutant mice (Cp−/−Hephsla) were generated by starting with C57BL/6 Cp null mice (Cp−/−) (F13 N12), re-derived from the original SvJ/129 Cp null mice strain (Harris et al., 1999). These were crossed with the naturally occurring Heph mutant mice (sla), originally identified by Jackson Laboratories and characterized by Vulpe et al (Vulpe et al., 1999). Since Heph is X-linked, we use Hephsla to represent either Hephsla/sla or Hephsla/Y. Our mating strategy generated single and double-mutant mice on a C57BL/6J background. Mice were maintained in the Johns Hopkins and University of Pennsylvania Animal Facilities where they were fed ad libitum with chow containing 300ppm iron and maintained on a 12 h/12 h light/dark cycle. For most of the experiments, 6mo animals were used unless otherwise indicated.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Whole brains obtained from 6mo WT, Cp−/−, Hephsla and Cp−/−Hephsla (n=3 or more, as indicated) were analyzed using quantitative real-time PCR for gene expression. RNA isolation was performed with an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The RNA was quantified with a spectrophotometer and stored at −80°C. cDNA was synthesized using TaqMan reverse transcription reagents (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. TaqMan gene expression assays were obtained from Applied Biosystems and used for PCR analysis. Probes used were ceruloplasmin, Cp (Mm00432654_m1) and hephaestin, Heph (Mm00515970_m1), transferrin receptor (Tfrc, Mm00441941_m1), glial fibrillary acidic protein, GFAP (Mm01253033_m1), tyrosine hydroxylase, Th (Mm00447557_m1), Purkinje cell protein 2 (L7), Pcp2 (Mm00435514_m1 ), myelin basic protein, Mbp (Mm01266402_m1), and EGF-like module containing, mucin-like, hormone receptor-like sequence 1(Emr1, Mm00802529_m1). Eukaryotic 18S rRNA (Hs99999901_s1) served as an internal control because of its constant expression level across the studied sample sets. Real-time TaqMan RT-PCR (Applied Biosystems) was performed on an ABI Prism 7500 sequence detection system using the ΔΔCT method, which provides normalized expression values. The amount of target mRNA was compared among the groups of interest. All reactions were performed with technical triplicates (three real-time PCR replicates per mouse).

Immunofluorescence

The brains from the mutant mice and WT controls (n=3 each) fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 2h were cryoprotected in 30% sucrose overnight and then embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound (OCT; Tissue-Tek, Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA). Immunofluorescence labeling was performed on 10μm thick sections as previously published for the retina (Hadziahmetovic et al., 2008). Primary antibodies used are listed in Table 1. Primary antibody reactivity was detected using fluorophore-labeled secondary antibodies (Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, PA). Control sections were treated identically but with omission of primary antibody. Sections were analyzed by fluorescence microscopy with identical exposure parameters using the Nikon TE300 microscope with ImagePro software.

Table 1. Primary Antibody Table.

| Name | Species | Company | Dilution |

|---|---|---|---|

| L ferritin (E17) | rabbit | Kind gift from Paolo Arosio, University of Brescia |

1:200 |

| H ferritin | chicken | Abcam, Cambridge, MA | 1:100 |

|

Transferrin

Receptor |

rat | AbD Serotec, Raleigh, NC | 1:250 |

| GFAP | rat | Invitrogen Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY |

1:100 |

| MDA | rabbit | Alpha Diagnostics, Intl. Inc., San Diego, CA |

1:100 |

|

Tyrosine

Hydroxylase |

rabbit | Millipore, Billerica, MA | 1:200 |

| SMI32 | mouse | Covance, Princeton, NJ | 1:50 |

| F4/80 | rat | Abcam, Cambridge, MA | 1:100 |

| CD31 | rabbit | Abcam, Cambridge, MA | 1:100 |

| MBP | rabbit | Abcam, Cambridge, MA | 1:50 |

| NeuN | rabbit | Abcam, Cambridge, MA | 1:50 |

Table lists names, species, companies, and dilutions of primary antibodies used for immunofluorescence.

Stereological analysis of TH neurons in the substantia nigra

TH-positive and total neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) were counted in anti-TH and Nissl stained sections, respectively. Stereological counting was performed as described (Kitada et al., 2009) with a few differences as follows. Brains were fixed in 70% ethanol/150mM NaCl and sectioned at 10μm thickness. Every tenth section was stained with an anti-tyrosine hydroxylase polyclonal antibody (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Three brains were analyzed for each group. For Nissl stain, paraffin-embedded tissue sections adjacent to sections stained with anti-TH were deparaffinized and hydrated through a series of graded ethanol followed by water. Sections were stained with 0.5% cresyl violet acetate/0.3% acetic acid, then washed with water, dehydrated with a series of graded ethanol, and mounted.

Iron staining

A modified DAB-Perls method was used for iron staining (Hahn et al., 2004). Sections were placed in 10% potassium ferrocyanide/20% hydrochloric acid for 30 min, then stained with DAB. The brains from each group of mice (n=3 each) were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 2h, then cryoprotected in 30% sucrose overnight and then embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound (OCT; Tissue-Tek, Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA). Sections were 10μm thick.

Quantitative Iron Detection

Total non-heme iron was quantified using a bathophenanthroline-based spectrophotometric protocol (Torrance and Bothwell, 1968). Briefly, tissues were weighed and then treated overnight at 65 °C in acid digest solution (0.1% trichloroacetic acid and 0.03 M HCl). After digestion, the tissue-acid mixture was vigorously vortexed. Following digestion, samples were allowed to cool to room temperature and then centrifuged for 25 minutes at 1200 × g (at room temperature). The supernatant (20μL) was added to 1 mL of chromagen reagent (2.25M sodium acetate pretreated with Chelex 100, 0.01% bathophenanthroline, and 0.1% thioglycolic acid). The absorbance was read at 535nm. Iron level was expressed as μg of iron per gram tissue and was assessed comparing absorbance of tissue-chromagen samples to serial dilutions of iron standard (Sigma–Aldrich, Inc., St Louis, MO).

Quantification of dopamine and its metabolites

HPLC analysis was used to measure levels of dopamine and its metabolites, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC) and homovanillic acid (HVA), in mouse striatum. Fresh mouse brains were dissected and the striatum isolated from five 6mo Cp−/−Hephsla mice and five age-matched controls. Samples were sonicated in 0.1M perchloric acid containing 0.01% ascorbic acid and 25μg/mL 3,4-dihydrobenzylamine as an internal standard. After centrifugation (15,000 × g, 15 min, 4°C), the supernatant was injected into a C18-reverse phase RP-80 catecholamine column (ESA, Bedford, MA). Peaks were detected by a Coulochem 5100 A Detector (ESA Inc., Chelmsford, MA).

Quantification of oxidative stress markers in brain homogenates

ELISA kits (Cell Biolabs, San Diego, CA) were used to measure HNE-His adducts and protein carbonyl levels as markers of lipid and protein oxidative damage, respectively. Mouse brains were collected and homogenized in PBS (at 1:3 w/v ratio) containing protease inhibitor phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride (PMSF, 100μM; EMD, Gibbstown, NJ). Assays were performed according to the manufacturers’ instructions. Levels of HNE-His and protein carbonyls were determined by comparing the absorbance produced by the samples with that of a calibration curve constructed with HNE-BSA (for HNE-His) or carbonyl-BSA standards (for protein carbonyls).

Behavior testing

Mice underwent motorbehavioral testing at 4mo as described previously (Khan et al., 2004). At the time of testing, the mice had no grossly detectable tremor or gait disturbance.

Rotarod

Coordinated motor skills were assessed via the rotarod test (Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH). Animals were placed on top of a 4cm diameter rod. After an equilibration period, the rotation speed was increased from 4 to 20rpm over a 5min period; the average time to falling was determined from three trials for each mouse.

Cling test

Climbing and hanging skills were assessed via the cling test. A 20 × 20cm platform with a 6mm grid of wire mesh surrounded by a 5cm frame was suspended 50cm above a soft landing area such that the mice could not escape the platform except by falling. Mice were placed on top of the frame and allowed to habituate for 60 sec followed by a grid rotation of 90° and hold in the vertical position for 60 sec. It was then rotated another 90° and held in the inverted position for 60 sec. The average time to falling was determined from three trials for each mouse.

Gross motor activity

Photocell activity chambers were used to quantify the gross motor activity of the mice. The chambers consisted of 20 × 40cm Plexiglass boxes with four infrared beams spanning the short axis and eight infrared beams spanning the long axis (San Diego Instruments, San Diego, CA). Single mice were placed in the chambers at the onset of the normally active nocturnal period. Beam breaks were recorded automatically by computer every 10 min for 10h with no habituation period.

Grip strength

A grip strength meter was used as an indicator of neuromuscular function. Briefly, mice were allowed to hold the grid, which was then pulled back horizontally until the grip was released. The force applied to the bar at the moment the grasp was released was recorded as the grip strength (pounds).

Statistical analysis

One-way ANOVA was used to analyze the behavior data. Student’s t-test analysis was used to compare the iron levels, dopamine metabolites, immunoreactive neuron numbers and mRNA levels between WT and Cp−/−Hephsla groups. Log Rank for Kaplan-Meier survival curve was performed with statistical GraphPad Prism 5 software (GraphPad Software, Inc. San Diego CA, USA). A p-value of <0.05 was set as the requirement for statistical significance.

Results

Cp and Heph mRNAs were present in the mouse brain and markedly diminished in DKO

We studied mice that were Cp−/− (knockout, null) combined with either Hephsla/sla (sex-linked anemia) or Heph−/− (knockout, null). For most of the studies, only Hephsla/sla, a hypomorph, (Vulpe et al, 1999) was available. Hephsla has two exons near the 3’ end of the gene deleted, resulting in markedly diminished protein levels. Heph is on the X chromosome, so females are Hephsla/sla and males are Hephsla/Y. Because we observed no sex effect on the results presented below, we refer to both Hephsla/sla and Hephsla/Y as Hephsla. More recently, we used germline recombination of a floxed Heph allele to generate a systemic knockout (Heph−/−), which makes no Heph protein (Wolkow et al. 2012, Fuqua et al., 2014). These mice were also used in some of the studies below.

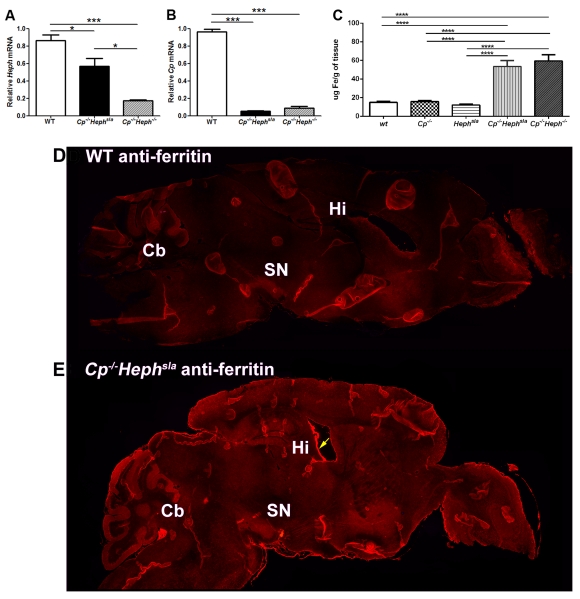

To assess brain expression of Cp and Heph, qPCR analysis was performed on brains from 6mo WT mice. Both genes were amplified at approximately cycle 25/40, suggesting intermediate mRNA levels compared to the abundant 18S endogenous control, which consistently amplified at cycle 10. Age-matched Cp−/−Hephsla and Cp−/−Heph−/− had significantly lower levels of Cp and Heph mRNA than WT (Figure 1A, B). In brains from Cp−/−Heph−/− mice, Heph mRNA levels were lower than in Cp−/−Hephsla as expected since the Heph−/− KO allele has exon 2 deleted. This renders subsequent exons out of frame leading to nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. A low level of Heph mRNA is still detected in the Heph−/− KO, as the primers and probe are located outside of the deleted exon. Western analysis shows that the exon 2 deletion in the Heph−/− KO mice results in loss of Heph protein (Fuqua et al. 2014).

Figure 1. Comparison of Cp and Heph mRNA, iron, and ferritin in brains from WT, Cp−/−, Hephsla, Cp−/−Hephsla, and Cp−/−Heph−/− mice.

A) Quantitative PCR for Heph from mRNA of whole brains from mice of the indicated genotypes. WT (n=5) Cp−/−Hephsla (n=3) and Cp−/−Heph−/− (n=3) mRNA levels are displayed as mean values (±S.E.M). *Significant difference (P<0.05), *** (P<0.001).

B) Same as A, except qPCR is for Cp.

C) Graph of whole brain non-heme iron levels in 5.5 mo mice of the indicated genotypes (n=3-5 each, **** p<0.0001).

D) L-ferritin immunolabeling (red) of whole brain from WT mouse. Cb: cerebellum. SN: substantia nigra. Hi: hippocampus.

E) L-ferritin immunolabeling (red, same exposure as panel D) of whole brain from Cp−/−Hephsla mouse. Arrow indicates choroid plexus.

Regionally increased iron in Cp−/−Hephsla and Cp−/−Heph−/− brains

At 5.5 mo, Cp−/−Hephsla mice had significantly higher whole brain non-heme iron levels than WT controls (Figure 1C). In contrast, neither Cp nor Heph single-mutants had elevated brain iron levels relative to WT mice. Iron levels in brains from Cp−/−Hephsla and Cp−/−Heph−/− were not significantly different from each other, suggesting that the mutation Hephsla renders Heph unable to contribute to brain iron export.

To determine which brain regions had increased iron, we immunolabeled for ferritin. The expression of this gene is regulated by cytosolic labile iron levels through iron regulatory proteins IRP1 and IRP2. When labile iron levels are high, ferritin translation increases (Rouault, 2006). We have found immunolabeling for ferritin a more sensitive method to assess the cellular iron status than the Perls’ histochemical stain (Hadziahmetovic et al., 2008). In Cp−/−Hephsla brains compared to age-matched WT, ferritin label was increased in the cerebellum, substantia nigra, hippocampus, cortex, choroid plexus, and meninges (Figure 1 D, E).

Iron accumulates in glia within the SN

To determine whether dopaminergic neurons had increased iron, we double-labeled with anti-tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) and anti-ferritin (Figure 2A). In contrast to WT, where TH-positive cells had some ferritin co-labeling, Cp−/−Hephsla brains were remarkable for the absence of ferritin immunoreactivity in the TH-positive cells. Surrounding cells were brightly immunofluorescent, which lead to the appearance of a “black hole” representing each TH-positive cell, suggesting low iron levels in these neurons.

Figure 2. Nigral neurons in Cp−/−Hephsla brains have decreased ferritin levels and increased TfR levels relative to age-matched WT controls.

A) Fluorescence photomicrographs of 6mo Cp−/−Hephsla SN showing weaker H-ferritin immunoreactivity (red) in TH positive cells (green) relative to age-matched WT controls (n=3 each). Arrows indicate TH-positive cells. Scale bar represents 33.3μm.

(B) Stronger TfR immunoreactivity (red) in TH (green) positive cells (arrow heads) relative to age-matched WT controls (n=3 each) in the SNpc. Scale bar represents 33.3μm.

To confirm these findings, we also double-labeled with TH and transferrin receptor (TfR), since, in contrast to ferritin which is down-regulated by IRPs when intracellular iron is low, TfR is upregulated. Consistent with low intracellular iron in the dopaminergic cells, TfR co-labeled with TH in the Cp−/−Hephsla but not WT SNpc (Figure 2B).

To determine which cells in the SNpc have increased iron in the Cp−/−Hephsla mice, we co-labeled with ferritin and markers for glia. In Cp−/−Hephsla mice, there was strong ferritin label in astrocytes marked with glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), oligodendrocytes marked with myelin basic protein (MBP), and microglia marked with F4/80 (Figure 3). Also, there was ferritin labeling just outside the CD31 marked blood vessels, a location consistent with the endfeet of astrocytes, which help control the flux of nutrients across blood vessels (Obermeier et al., 2013).

Figure 3. GFAP, MBP and F4/80 but not CD31 co-label with ferritin in SNpc of Cp−/−Hephsla mice.

Fluorescence photomicrographs of 6mo Cp−/−Hephsla SNpc show strong co-immunoreactivity between L-ferritin and GFAP (n=3), and between H-ferritin and MBP (n=3), as well as between H-ferritin and F4/80 (n=3). There is close juxtaposition but no co-labeling between H-ferritin and CD31. The scale bar represents 33.3μm.

Cp−/−Hephsla brains have increased oxidative stress

Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction have been reported as key events in degeneration and death of dopaminergic neurons in the SN in Parkinson’s disease (Jenner et al., 1992, Sayre et al., 2001). In addition to increased iron content in the SN, it has been reported that oxidative stress in Parkinson’s disease manifests through elevated levels of oxidized and nitrated proteins (Alam et al., 1997) and increased lipid peroxidation (Jomova et al., 2010, Ruiperez et al., 2010). To assess the protein and lipid oxidation in our animal model, we measured 4-hydroxynonenal (HNE) and protein carbonyl levels by ELISA. Aldehydes such as HNE are major end products of lipid peroxidation. HNE forms covalent adducts with proteins, and these adducts can be quantified by ELISA. The whole-brain HNE levels were significantly higher in Cp−/−Hephsla mice relative to age-matched wild type controls (Figure 4A). Protein carbonyl levels were not significantly increased within the brains of Cp−/−Hephsla mice (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. Markers of oxidative stress and quantification of SN neurons and their metabolites in brain tissue of Cp−/−Hephsla and WT mice.

HNE-His adducts (μg HNE-His/μg total protein) and protein carbonyl (nmol/mg total protein) levels in brain homogenates (A and B; n=3 each). HNE-His levels show significant increase in Cp−/−Hephsla mice, relative to WT mice (p<0.05). Cp−/−Hephsla mice do not have a significant increase in protein carbonyl levels.

C) Stereological dopaminergic neuron quantification following tyrosine hydroxylase staining of paraffin-embedded sections revealed that the number of dopaminergic neurons was significantly lower in the SNpc of Cp−/−Hephsla mice relative to WT (n=3 each, * p < 0.001).

D) Total neuron quantification in the SNpc by Nissl stain showed fewer neurons in Cp−/−Hephsla mice relative to WT (n=3 each, * p < 0.001).

E) Mouse striatal tissue was analyzed by HPLC for dopamine (DA) and its metabolites 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC) and homovanillic acid (HVA) (n = 5, * p < 0.05).

Cp−/−Hephsla mice have decreased nigral dopaminergic neuron number and dopamine

We next sought to determine whether glial iron buildup, neuronal iron deficiency, and oxidative stress would cause loss of nigral dopaminergic neurons. No difference in neuron numbers was observed between Cp−/−Hephsla and WT at either one or two months (data not shown), indicating that the same number of nigral dopaminergic neurons were produced during development. However, analysis of 6mo Cp−/−Hephsla SNpc by stereology revealed significantly fewer TH-positive neurons relative to WT controls (Figure 4C). Additionally, Nissl stain revealed a significant decrease in total neuron count in the SNpc in the Cp−/−Hephsla mice relative to age-matched WT controls (Figure 4D). This result verified that loss of TH staining is due to cell loss and not to markedly decreased TH levels in viable dopaminergic neurons.

Next, we investigated dopamine and dopamine metabolite concentrations by HPLC to determine whether striatal levels were affected in these mice. Dopamine, DOPAC, and HVA were measured by HPLC on fresh tissue from striatum isolated from 6mo mice. These experiments demonstrated significantly lower concentrations of dopamine and HVA in the Cp−/−Hephsla mice relative to age-matched controls (Figure 4E).

Cellular iron distribution in Cp−/−Hephsla cerebellum

Ferritin immunolabeling of Cp−/−Hephsla cerebellum revealed a strong signal in the Bergmann glia of the molecular layer (Figure 5A). These are radial glia critical for cerebellar glutamate metabolism. In contrast, the neurons in the granular layer labeled with NeuN (for neuronal nuclei) and SMI32 (for neurofilament) had much less ferritin labeling (Figure 5B). Purkinje cells also had low ferritin levels. Conversely, many granular cell layer neurons had increased TfR (Figure 5C), which is consistent with low iron levels. Purkinje cell loss is associated with this cerebellar iron maldistribution (Figure 5D, E).

Figure 5. Fluorescence photomicrographs showing glial cell ferritin levels and Purkinje cell number in Cp−/−Hephsla mice (n=3).

A) Bergmann glia (arrows) co-labeling with GFAP and H-ferritin in Cp−/−Hephsla brains. ML: molecular layer. GL: granular layer. WM: white matter. Scale bar represents 100um.

B) Triple labeling of Cp−/−Hephsla brains with H-ferritin (red), NeuN, for neuronal nuclei (green), and SMI32, neurofilament (white). Arrows indicate Purkinje cells. Scale bar represents 50um.

C) Triple labeling of Cp−/−Hephsla brains with TfR (red), NeuN (green), and SMI32 (white). Arrows indicate Purkinje cells. Scale bar represents 50um.

D) Fluorescence photomicrographs of 6mo Cp−/−Hephsla show fewer Purkinje neurons in Cp−/−Hephsla mice compared with the WT controls. Anti-SMI32 (red) labels the Purkinje cells. The scale bar represents 100μm.

E) Purkinje neuron quantification following SMI32 staining of cryosections revealed that the number was significantly lower in the cerebellum of Cp−/−Hephsla mice relative to controls (n=3, * p < 0.01).

Motorbehavioral testing in Cp−/−Hephsla mice

To quantify gait, balance and strength, we assessed the number of beam breaks in the open field activity test, ability to stay on the rotarod, ability to hang using the cling test, and grip strength (Table 2). Mice were tested at 4mo of age when they had no gross behavioral abnormalities. Although locomotion testing, as assessed by the photocell beam break test, revealed no difference between Cp−/−Hephsla and control WT mice, Cp−/−Hephsla mice had severe deficits in motor coordination, balance, and strength (Table 2). Cp−/−Hephsla mice have focal areas of retinal degeneration beginning at age 6mo. There are no changes in the electroretinogram at 6mo. Therefore, at the age of motor function testing, visual impairment would not have been a factor. Both Cp−/−Hephsla and Cp−/−Heph−/− mice developed a disabling motor disorder between the ages of 6-9mo. They developed weakness, tremor, and occasional generalized seizure with post-ictal period. An example of the motor abnormalities in Cp−/−Hephsla mice, which can be ameliorated with deferiprone, is shown (Movie 1).

Table 2. Motor behavioral testing.

| Genotype | Photocell (# of beam breaks) |

Rotarod (sec) | Cling Test (sec) | Grip strength (lbs) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 23273.7±10249.8 | 278.2±41.1 | 173.8±10.9 | 0.063±0.02 |

| cp−/− | 29566.0±16770.8 | 281.8±20.5 | 180.0±0.0 | 0.062±0.02 |

| Hephsla | 24438.4±6467.9 | 276.7±27.8 | 171.0±20.1 | 0.060±0.02 |

| Cp−/−Hephsla | 23584.3±7837.2 | 29.1±15.8** | 98.7±25.8** | 0.028±0.005** |

Table demonstrates results of neurobehavioral testing across genotypes of 4mo mice.

p<0.001 (n=9 each).

Movie 1. Movement disorder in Cp−/−Hephsla mice.

All three mice are Cp−/−Hephsla. The mouse in the middle is 8mo and was treated with deferiprone from age 3mo to age 8mo. It shows normal behavior. The mouse on the left is 6mo, and the mouse on the right is 8mo; neither of these was treated with deferiprone.

Iron chelation with deferiprone protected against neurodegeneration

To determine whether iron chelation can prevent the neurodegeneration in Cp−/−Hephsla mice, we treated the mice with oral deferiprone in their drinking water (1mg/ml; approximately 150mg/kg/d) beginning at age 2-3mo. Compared to mice not receiving treatment, deferiprone-treated mice had significantly delayed onset of movement disorder, leading to prolonged lifespan (Figure 6A). BPS iron quantification showed lower brain iron levels in Cp−/−Hephsla mice treated with DFP compared to age and genotype-matched untreated mice (Figure 6B). Perls’ staining revealed diminished iron levels throughout the brain, including the cerebellum and SN (Figure 6 C-E).

Figure 6. Effects of DFP treatment on survival and brain iron levels in Cp−/−Hephsla mice.

A) There was significant lifespan extension in Cp−/−Hephsla mice treated with DFP (p<0.001) compared to untreated Cp−/−Hephsla. Lifespans of Cp−/−Hephsla versus Cp−/−Heph−/− were not significantly different.

B)Graph showing relative iron levels quantified using the BPS assay in whole brain homogenates from 8.5mo Cp−/−Hephsla mice. One group of mice had been treated with DFP 1mg/ml in the water bottle beginning at 2mo (n=3, <0.01).

C-E) DAB-enhanced Perls’ stain for iron. C) Whole brain. D) Cerebellum. E) Substantia nigra. The scale bar in C represents 500μm. The scale bar in D represents 200μm. The scale bar in E represents 100μm.

DFP protected against the loss of both dopaminergic neurons detected with anti-TH in the SN and Purkinje cells detected with anti-SMI32 in the cerebellum (Figure 7). TH-positive neurons from DFP treated mice still had high TfR levels at this timepoint (Figure 8).

Figure 7. The number of SN dopaminergic neurons and cerebellar Purkinje neurons is higher in Cp−/−Hephsla mice treated with DFP.

A) Fluorescence photomicrographs of 8.5mo Cp−/−Hephsla without DFP (left) or treated with DFP (right) showing higher numbers of dopaminergic neurons (anti-TH, red, arrows) in the treated group. The scale bar represents 100μm.

B) Fluorescence photomicrographs showing Purkinje neurons (anti-SMI32, red, arrowheads) in DFP-treated versus untreated groups. The scale bar represents 100μm.

C) Quantification of neurons stained as shown in A and B (n=3 mice each, * p < 0.05).

Figure 8. Fluorescence photomicrographs of SNpc showing TfR levels in dopaminergic neurons.

8.5mo Cp−/−Hephsla mice had TfR immunoreactivity (red) in TH-positive cells (green, arrows) regardless of the presence or absence of DFP treatment, as indicated. Scale bar represents 100μm.

To further assess iron status as well as the condition and number of different brain cell types, we measured levels of several mRNAs in Cp−/−Hephsla brains from mice that had or had not been treated with DFP. DFP increased transferrin receptor (TfR) mRNA levels in whole brain extracts, which is consistent with decreased iron levels (Figure 9). The Purkinje-cell mRNA PCP2, dopaminergic neuron marker TH, oligodendrocyte-specific MBP, and microglia/macrophage-specific F4/80 were all decreased in untreated Cp−/−Hephsla mice compared to WT. DFP treatment of the Cp−/−Hephsla mice protected against a decrease in these cell-type specific mRNAs. Astrocyte mRNA GFAP was diminished in Cp−/−Hephsla brains, with a trend toward higher levels in DFP-treated mice.

Figure 9. qPCR quantification of iron-related and cell-type specific mRNAs in total brain homogenates.

Relative quantities of the indicated mRNAs from whole brains of 6mo WT (n=5), 6mo Cp−/−Hephsla (n=3), 8.5mo Cp−/−Hephsla (n=3), and 8.5mo Cp−/−Hephsla treated with DFP (n=3) are displayed as mean values (±S.E.M). *(P<0.05), **(P<0.01), ***(P<0.001). Gene abbreviations are as follows. Tfrc: transferrin receptor, PCP2: Purkinje cell protein 2 (L7), TH: tyrosine hydroxylase, which labels dopaminergic neurons, F4/80: EGF-like module containing, mucin-like, hormone receptor-like sequence 1, which detects microglia/macrophages, MBP: myelin basic protein, which represents oligodendrocytes, GFAP: glial fibrillary acidic protein, which detects astrocytes.

Discussion

We tested herein whether the homologous multi-copper ferroxidases Cp and Heph may have complementary roles in brain iron homeostasis. To accomplish this, we generated mice deficient for both. These Cp−/−Hephsla mice exhibited iron accumulation within the SN, cerebellum, and hippocampus. Substantia nigra pars compacta TH-positive dopaminergic neurons had a decrease in ferritin and increase in transferrin receptor immunoreactivity, indicating these cells had low iron levels. In contrast, astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and microglia within the SN had high iron levels driving increased ferritin. There was increased oxidative stress and loss of dopaminergic cells within the SN. Consistent with the loss of dopaminergic neurons, dopamine and its metabolite HVA, were also diminished. As in the SN, cerebellar neurons had low iron levels, and glia had high levels. Purkinje cell number was reduced. Cp−/−Hephsla mice displayed a severe motor impairment and lifespan limited to 6-9mo. Treatment with the iron chelator deferiprone diminished brain iron levels, partially protected against loss of glia and neurons, and extended lifespan.

In patients with aceruloplasminemia, loss of Cp leads to impaired iron export from several tissues, resulting in iron overload in the retina, brain, and pancreas. This iron overload contributes to the hallmark clinical triad of retinal degeneration, diabetes and movement disorder (Harris et al., 1995, McNeill and Chinnery, 2011). Iron overload-induced, age-related changes have also been observed in the cerebellum of Cp−/− mice (Jeong and David, 2006), which showed iron accumulation mainly in astrocytes accompanied by significant loss of these cells and Purkinje cells at age 24mo. These mice showed a defect in motor coordination at 16mo as assessed by the rotarod assay, associated with a loss of brainstem dopaminergic neurons. These results are consistent with demonstrated Cp expression in astrocytes and Cp-facilitated iron export, in cooperation with ferroportin, in cultured astrocytes (Jeong and David, 2006). In our Cp−/− mice, we focused on total brain iron levels at a younger age (6mo) and motorbehavioral testing (at age 4mo), and there was no difference from WT. Thus, in young Cp−/− mice, increased total brain iron or movement disorder was not apparent, possibly due to the compensatory function of Heph.

Heph is also expressed in the brain, primarily in oligodendrocytes and microglia (Schulz et al., 2011). Heph is expressed by mature spinal cord oligodendrocytes and plays a role in iron efflux from these cells. Gray and white matter spinal cord oligodendrocytes use different combinations of Cp and Heph to maintain iron homeostasis (Schulz et al., 2011). In our experiments, 24mo Hephsla mice had neither increased total, non-heme brain iron relative to WT controls, nor gross motor dysfunction (data not shown). To determine whether Cp and Heph can serve complementary roles, we generated Cp−/−Hephsla and Cp−/−Heph−/− mice, which had increased total brain iron by 6mo. Since Cp and Heph primarily localize to glia, we hypothesized that Cp−/−Hephsla might have glial iron overload but neuronal iron deficiency. Our ferritin and TfR immunolabeling results support this hypothesis.

Increased iron in the Cp−/−Hephsla and Cp−/−Heph−/− brain parenchyma indicates that Cp and Heph are not necessary for iron import across the blood-brain barrier (BBB). They are also not necessary for iron transfer from the gut to the blood, indicating the presence of alternative (albeit less efficient) iron uptake mechanisms. Despite diminished serum iron, the mice accumulate glial iron. This is consistent with iron import into the brain and impaired export from glial cells. These results suggest that another ferroxidase such as zyklopen (Chen et al., 2010), which we find expressed in the brain (by qPCR amplification at cycle 30/40), might associate with ferroportin to facilitate iron export from the vascular endothelial cells into the brain.

Death of neurons in Cp−/−Hephsla mice may result from glial iron overload causing loss of glial support. This increase in glial iron could injure or kill glia, depriving neurons of required nutrients or neurotrophic factors. Increased intracellular glial iron, especially within microglia, might also induce them to secrete harmful molecules (Zhang et al., 2014). Similarly, neurotoxin-induced Parkinson’s rodents have increased levels of the iron in microglia (Salazar et al., 2008). Here, too, excess iron contributes to microglial activation in the SN (Peng et al., 2009). Iron chelation in this context can protect against loss of dopaminergic neurons (Kaur et al., 2003).

In addition to elevated glial iron, Parkinson’s disease brains have increased neuronal iron, which could be attributed, in part, to the observed increased levels of divalent metal transporter 1 in the SN (Morris et al. 1994, Salazar et al. 2008, Ayton et al. 2015). Because PD brains have increased neuronal iron in the SN while neurons from Cp−/−Hephsla mice are iron deficient, this aspect of PD is not modeled by the Cp−/−Hephsla mice.

Cp−/−Hephsla mice have diminished Heph protein levels and ferroxidase activity. Ferroxidase assays in enterocytes reveal activity ranging from 5-20% of normal; the mice with higher ferroxidase activity generally have later onset neurodegeneration (data not shown). Due to this residual Heph function, we generated a Heph null allele, which does not make any Heph protein (Wolkow et al., 2012). The brain iron levels and distribution, as well as motor behavior and lifespan of the Cp−/−Hephsla and Cp−/−Heph−/− mice, are quite similar. This indicates that residual protein produced by the Hephsla allele is insufficient for brain iron homeostasis.

The oral iron chelator deferiprone (DFP), FDA-approved for iron overload in thalassemia, diminished brain iron levels and extended the lifespan of Cp−/−Hephsla mice. We selected this chelator because it crosses the BBB (Fredenburg et al., 1996) and has shown evidence of clinical efficacy in Friedreich’s ataxia, a brain iron overload disorder (Boddaert et al., 2007), as well as in Parkinson’s disease (Devos et al., 2014). Also, its affinity for iron is lower than that of other chelators, such as deferoxamine (Devanur et al. 2008), so it is less likely to cause iron deficiency. Indeed, the DFP-treated Cp−/−Hephsla mice had an increased hematocrit, probably resulting from DFP-mediated transfer of iron to transferrin. DFP-mediated iron transfer to transferrin has been demonstrated (Sohn et al., 2011). Our results are consistent with a recent study showing DFP-mediated protection against diminished rotarod performance and loss of dopaminergic neurons in Cp−/− mice (Ayton et al., 2013).

Our demonstration that early treatment with DFP can protect against iron-induced neurodegeneration in Cp−/−Hephsla mice supports other observations suggesting that it may prove clinically useful in neurodegenerative conditions involving iron overload (Boddaert et al, 2007, Cossu et al., 2014, Pandolfo, 2014). Although in a case of aceruloplasminemia, treatment with deferiprone 75mg/kg/day for 6 months did not benefit the patient (Mariani et al., 2004), the dose, for a patient without iron overload, may have been too great, as 60 mg/kg/day worsened some patients with Friedreich Ataxia (Pandolfo 2014). Iron chelation is not approved outside of the treatment of iron overload in thalassemia syndromes, but clinical trials in various neurodegenerative conditions emphasize the need weekly monitoring of neutrophil count, as approximately 1-2% of patients treated with DFP develop reversible agranulocytosis (ApoPharma Inc., Ferriprox (deferiprone) Prescribing Information and Medication Guide, 2012). A case report using deferasirox, another iron chelator, in a patient with aceruloplasminemia, suggested improvement in choreoathetosis and unsteady gait after treatment (Suzuki et al., 2013).

Cp−/−Hephsla mice are anemic (data not shown). However, this anemia does not account for their motor deficits. Cp+/+, Cp−/−, and Hephsla mice made anemic by serial phlebotomy over 6 months to a Hb of 4.5 g/dL, comparable to Cp−/−Hephsla mice, never developed any motor deficits, iron accumulation in the CNS, or dopaminergic neuronal drop-out (data not shown), confirming that anemia alone does not result in the observed phenotype.

Cp−/−Hephsla mice have brain iron accumulation with loss of dopaminergic neurons, movement disorder, and premature death. Comparison to Cp−/− and Hephsla single mutants suggests that these two ferroxidases are able to partially compensate for each other’s brain iron transport functions. These mice as well as the Cp−/−Heph−/− mice will prove useful in future studies on the roles of these ferroxidases in brain iron transport and on mechanisms of brain neurodegeneration involving iron toxicity.

Abbreviations

- Cp

Ceruloplasmin

- Fpn

Ferroportin

- Heph

Hephaestin

- KO

Knockout

- WT

Wild Type

- TH

Tyrosine Hydroxylase

- TfR

Transferrin Receptor

- SNpc

Substantia Nigra Pars Compacta

- DKO

Double Knockout

- SN

Substantia Nigra

- Sla

Sex-Linked Anemia

- GFAP

Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein

References

- Alam ZI, Daniel SE, Lees AJ, Marsden DC, Jenner P, Halliwell B. A generalised increase in protein carbonyls in the brain in Parkinson’s but not incidental Lewy body disease. J Neurochem. 1997;69:1326–1329. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69031326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson GJ, Frazer DM, McKie AT, Wilkins SJ, Vulpe CD. The expression and regulation of the iron transport molecules hephaestin and IREG1: implications for the control of iron export from the small intestine. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2002;36:137–146. doi: 10.1385/CBB:36:2-3:137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayton S, Lei P, Adlard PA, Volitakis I, Cherny RA, Bush AI, Finkelstein DI. Iron accumulation confers neurotoxicity to a vulnerable population of nigral neurons: implications for Parkinson’s disease. Molecular neurodegeneration. 2014;9:27. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-9-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayton S, Lei P, Duce JA, Wong BX, Sedjahtera A, Adlard PA, Bush AI, Finkelstein DI. Ceruloplasmin dysfunction and therapeutic potential for Parkinson disease. Ann Neurol. 2013;73:554–559. doi: 10.1002/ana.23817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boddaert N, Le Quan Sang KH, Rotig A, Leroy-Willig A, Gallet S, Brunelle F, Sidi D, Thalabard JC, Munnich A, Cabantchik ZI. Selective iron chelation in Friedreich ataxia: biologic and clinical implications. Blood. 2007;110:401–408. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-065433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capo CR, Arciello M, Squitti R, Cassetta E, Rossini PM, Calabrese L, Rossi L. Features of ceruloplasmin in the cerebrospinal fluid of Alzheimer’s disease patients. Biometals : an international journal on the role of metal ions in biology, biochemistry, and medicine. 2008;21:367–372. doi: 10.1007/s10534-007-9125-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Attieh ZK, Syed BA, Kuo YM, Stevens V, Fuqua BK, Andersen HS, Naylor CE, Evans RW, Gambling L, Danzeisen R, Bacouri-Haidar M, Usta J, Vulpe CD, McArdle HJ. Identification of zyklopen, a new member of the vertebrate multicopper ferroxidase family, and characterization in rodents and human cells. J Nutr. 2010;140:1728–1735. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.117531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cossu G, Abbruzzese G, Matta G, Murgia D, Melis M, Ricchi V, Galanello R, Barella S, Origa R, Balocco M, Pelosin E, Marchese R, Ruffinengo U, Forni GL. Efficacy and safety of deferiprone for the treatment of pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration (PKAN) and neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (NBIA): results from a four years follow-up. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2014;20:651–4. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Domenico I, Ward DM, di Patti MC, Jeong SY, David S, Musci G, Kaplan J. Ferroxidase activity is required for the stability of cell surface ferroportin in cells expressing GPI-ceruloplasmin. Embo J. 2007;26:2823–2831. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devanur LD, Evans RW, Evans PJ, Hider RC. Chelator-facilitated removal of iron from transferrin: relevance to combined chelation therapy. The Biochemical journal. 2008;409:439–447. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devos D, Moreau C, Devedjian JC, Kluza J, Petrault M, Laloux C, Jonneaux A, Ryckewaert G, Garcon G, Rouaix N, Duhamel A, Jissendi P, Dujardin K, Auger F, Ravasi L, Hopes L, Grolez G, Firdaus W, Sablonniere B, Strubi-Vuillaume I, Zahr N, Destee A, Corvol JC, Poltl D, Leist M, Rose C, Defebvre L, Marchetti P, Cabantchik ZI, Bordet R. Targeting chelatable iron as a therapeutic modality in Parkinson’s disease. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2014;21:195–210. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunaief JL, Richa C, Franks EP, Schultze RL, Aleman TS, Schenck JF, Zimmerman EA, Brooks DG. Macular degeneration in a patient with aceruloplasminemia, a disease associated with retinal iron overload. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:1062–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards JA, Bannerman RM. Hereditary defect of intestinal iron transport in mice with sex-linked anemia. J Clin Invest. 1970;49:1869–1871. doi: 10.1172/JCI106405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredenburg AM, Sethi RK, Allen DD, Yokel RA. The pharmacokinetics and blood-brain barrier permeation of the chelators 1,2 dimethly-, 1,2 diethyl-, and 1-[ethan-1’ol]-2-methyl-3-hydroxypyridin-4-one in the rat. Toxicology. 1996;108:191–199. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(95)03301-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuqua BK, Lu Y, Darshan D, Frazer DM, Wilkins SJ, Wolkow N, Bell AG, Hsu J, Yu CC, Chen H, Dunaief JL, Anderson GJ, Vulpe CD. The Multicopper Ferroxidase Hephaestin Enhances Intestinal Iron Absorption in Mice. PLoS One. 2014;9:e98792. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadziahmetovic M, Dentchev T, Song Y, Haddad N, He X, Hahn P, Pratico D, Wen R, Harris ZL, Lambris JD, Beard J, Dunaief JL. Ceruloplasmin/hephaestin knockout mice model morphologic and molecular features of AMD. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2008;49:2728–2736. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn P, Qian Y, Dentchev T, Chen L, Beard J, Harris ZL, Dunaief JL. Disruption of ceruloplasmin and hephaestin in mice causes retinal iron overload and retinal degeneration with features of age-related macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:13850–13855. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405146101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han O, Kim EY. Colocalization of ferroportin-1 with hephaestin on the basolateral membrane of human intestinal absorptive cells. J Cell Biochem. 2007;101:1000–1010. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris ZL, Durley AP, Man TK, Gitlin JD. Targeted gene disruption reveals an essential role for ceruloplasmin in cellular iron efflux. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:10812–10817. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris ZL, Takahashi Y, Miyajima H, Serizawa M, MacGillivray RT, Gitlin JD. Aceruloplasminemia: molecular characterization of this disorder of iron metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:2539–2543. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellman NE, Kono S, Mancini GM, Hoogeboom AJ, De Jong GJ, Gitlin JD. Mechanisms of copper incorporation into human ceruloplasmin. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:46632–46638. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206246200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenner P, Dexter DT, Sian J, Schapira AH, Marsden CD. Oxidative stress as a cause of nigral cell death in Parkinson’s disease and incidental Lewy body disease. The Royal Kings and Queens Parkinson’s Disease Research Group. Ann Neurol. 1992;32(Suppl):S82–87. doi: 10.1002/ana.410320714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong SY, David S. Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored ceruloplasmin is required for iron efflux from cells in the central nervous system. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:27144–27148. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301988200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong SY, David S. Age-related changes in iron homeostasis and cell death in the cerebellum of ceruloplasmin-deficient mice. J Neurosci. 2006;26:9810–9819. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2922-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jomova K, Vondrakova D, Lawson M, Valko M. Metals, oxidative stress and neurodegenerative disorders. Mol Cell Biochem. 2010;345:91–104. doi: 10.1007/s11010-010-0563-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur D, Yantiri F, Rajagopalan S, Kumar J, Mo JQ, Boonplueang R, Viswanath V, Jacobs R, Yang L, Beal MF, DiMonte D, Volitaskis I, Ellerby L, Cherny RA, Bush AI, Andersen JK. Genetic or pharmacological iron chelation prevents MPTP-induced neurotoxicity in vivo: a novel therapy for Parkinson’s disease. Neuron. 2003;37:899–909. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00126-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan Z, Carey J, Park HJ, Lehar M, Lasker D, Jinnah HA. Abnormal motor behavior and vestibular dysfunction in the stargazer mouse mutant. Neuroscience. 2004;127:785–796. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.05.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitada T, Tong Y, Gautier CA, Shen J. Absence of nigral degeneration in aged parkin/DJ-1/PINK1 triple knockout mice. J Neurochem. 2009;111:696–702. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06350.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klomp LW, Gitlin JD. Expression of the ceruloplasmin gene in the human retina and brain: implications for a pathogenic model in aceruloplasminemia. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5:1989–1996. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.12.1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kono S, Yoshida K, Tomosugi N, Terada T, Hamaya Y, Kanaoka S, Miyajima H. Biological effects of mutant ceruloplasmin on hepcidin-mediated internalization of ferroportin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1802:968–975. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariani R, Arosio C, Pelucchi S, Grisoli M, Piga A, Trombini P, Piperno A. Iron chelation therapy in aceruloplasminaemia: study of a patient with a novel missense mutation. Gut. 2004;53:756–8. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.030429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy RC, Park YH, Kosman DJ. sAPP modulates iron efflux from brain microvascular endothelial cells by stabilizing the ferrous iron exporter ferroportin. EMBO Rep. 2014;15:809–815. doi: 10.15252/embr.201338064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeill A, Chinnery PF. Neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation. Handb Clin Neurol. 2011;100:161–172. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-52014-2.00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris CM, Candy JM, Omar S, Bloxham CA, Edwardson JA. Transferrin receptors in the parkinsonian midbrain. Neuropathology and applied neurobiology. 1994;20:468–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1994.tb00997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obermeier B, Daneman R, Ransohoff RM. Development, maintenance and disruption of the blood-brain barrier. Nat Med. 2013;19:1584–1596. doi: 10.1038/nm.3407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto N, Wada S, Oga T, Kawabata Y, Baba Y, Habu D, Takeda Z, Wada Y. Hereditary ceruloplasmin deficiency with hemosiderosis. Human genetics. 1996;97:755–758. doi: 10.1007/BF02346185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandolfo M, Arpa J, Delatycki MB, Le Quan Sang KH, Mariotti C, Munnich A, Sanz-Gallego I, Tai G, Tarnopolsky MA, Taroni F, Spino M, Tricta F. Deferiprone in Friedreich ataxia: a 6-month randomized controlled trial. Ann Neurol. 2014;76:509–21. doi: 10.1002/ana.24248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel BN, David S. A novel glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored form of ceruloplasmin is expressed by mammalian astrocytes. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:20185–20190. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.32.20185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng J, Stevenson FF, Oo ML, Andersen JK. Iron-enhanced paraquat-mediated dopaminergic cell death due to increased oxidative stress as a consequence of microglial activation. Free radical biology & medicine. 2009;46:312–320. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.10.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponka P. Hereditary causes of disturbed iron homeostasis in the central nervous system. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2004;1012:267–281. doi: 10.1196/annals.1306.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouault TA. The role of iron regulatory proteins in mammalian iron homeostasis and disease. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:406–414. doi: 10.1038/nchembio807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiperez V, Darios F, Davletov B. Alpha-synuclein, lipids and Parkinson’s disease. Prog Lipid Res. 2010;49:420–428. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar J, Mena N, Hunot S, Prigent A, Alvarez-Fischer D, Arredondo M, Duyckaerts C, Sazdovitch V, Zhao L, Garrick LM, Nunez MT, Garrick MD, Raisman-Vozari R, Hirsch EC. Divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1) contributes to neurodegeneration in animal models of Parkinson’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:18578–18583. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804373105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar J, Seshadri V, Tripoulas NA, Ketterer ME, Fox PL. Role of ceruloplasmin in macrophage iron efflux during hypoxia. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:44018–44024. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304926200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayre LM, Smith MA, Perry G. Chemistry and biochemistry of oxidative stress in neurodegenerative disease. Curr Med Chem. 2001;8:721–738. doi: 10.2174/0929867013372922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz K, Vulpe CD, Harris LZ, David S. Iron efflux from oligodendrocytes is differentially regulated in gray and white matter. J Neurosci. 2011;31:13301–13311. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2838-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohn YS, Mitterstiller AM, Breuer W, Weiss G, Cabantchik ZI. Rescuing iron-overloaded macrophages by conservative relocation of the accumulated metal. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;164:406–418. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01120.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Yoshida K, Aburakawa Y, Kuroda K, Kimura T, Terada T, Kono S, Miyajima H, Yahara O. Effectiveness of oral iron chelator treatment with deferasirox in an aceruloplasminemia patient with a novel ceruloplasmin gene mutation. Intern Med. 2013;52(13):1527–30. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.52.0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrance JD, Bothwell TH. A simple technique for measuring storage iron concentrations in formalinised liver samples. S Afr J Med Sci. 1968;33:9–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vulpe CD, Kuo YM, Murphy TL, Cowley L, Askwith C, Libina N, Gitschier J, Anderson GJ. Hephaestin, a ceruloplasmin homologue implicated in intestinal iron transport, is defective in the sla mouse. Nature genetics. 1999;21:195–199. doi: 10.1038/5979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolkow N, Song D, Song Y, Chu S, Hadziahmetovic M, Lee JC, Iacovelli J, Grieco S, Dunaief JL. Ferroxidase hephaestin’s cell-autonomous role in the retinal pigment epithelium. Am J Pathol. 2012;180:1614–1624. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.12.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolkow N, Song Y, Wu TD, Qian J, Guerquin-Kern JL, Dunaief JL. Aceruloplasminemia Retinal Histopathologic Manifestations and Iron-Mediated Melanosome Degradation. Arch Ophthalmol-Chic. 2011;129:1466–1474. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Yan ZF, Gao JH, Sun L, Huang XY, Liu Z, Yu SY, Cao CJ, Zuo LJ, Chen ZJ, Hu Y, Wang F, Hong JS, Wang XM. Role and mechanism of microglial activation in iron-induced selective and progressive dopaminergic neurodegeneration. Mol Neurobiol. 2014;49:1153–1165. doi: 10.1007/s12035-013-8586-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]