Abstract

Heterosexual anal intercourse (HAI) is not an uncommon behavior and it confers a higher risk of HIV transmission than vaginal intercourse. We examined data from heterosexuals recruited in 20 US cities for the 2013 National HIV Behavioral Surveillance system. We assessed correlates of reporting HAI in the previous year. Then, among people reporting HAI in the past year, we assessed what event-level factors are associated with having HAI at last sex. Thirty percent of women and 35% of men reported HAI in the past year. Among people who had HAI in the past year, those who had HAI at last sex were more likely to have a partner who was HIV-positive or of unknown status or to have exchanged money or drugs for sex at last sex. Information that highlights the risk of HIV transmission associated with HAI would complement existing HIV prevention messages focused on heterosexuals in the U.S.

Keywords: heterosexual anal intercourse, HIV/AIDS, high-risk behavior, condom use

Introduction

Heterosexual anal intercourse (HAI) is not an uncommon behavior with 36% of women and 44% of men 25–44 years old in the United States reporting ever having HAI in their lifetime (1). There is evidence that the prevalence of HAI may be increasing in recent years, which may be due to a true increase in the behavior over time or heterosexuals becoming more comfortable reporting the behavior (2, 3). In addition, HAI confers an increased risk for HIV acquisition as compared to vaginal intercourse. Based on a meta-analysis, acquisition of HIV is 18-times as likely to occur during receptive HAI as during receptive vaginal intercourse among heterosexuals (4). However, HAI still remains under-emphasized in prevention messages for heterosexuals.

Previous research has shown that HAI is associated with a variety of risky behaviors, including drug use (5–7), multiple partners (6, 8–10), concurrent partners (8), and exchange sex (6–8, 11), suggesting that people who engage in HAI are in a higher risk population for acquisition of HIV and sexually transmitted infections (STI). This is supported by studies that also show a higher prevalence of STIs among those who engage in HAI (12). Additionally, condom use is uncommon during HAI, with some studies indicating that condom use during HAI is less common than condom use during vaginal sex (13, 14).

It is important to characterize the groups with higher prevalence of this behavior, and, among those who are engaging in this behavior, what appears to influence condom use, in order to better tailor prevention messages. Several previous studies have looked at the association between having HAI and demographic characteristics and risk behaviors, but the HAI measure is typically past year or three months. More information could be gained by looking at a particular sexual event, such as, the characteristics of the partner and context of the event that are associated with having HAI. Knowing who people have HAI with and in what context could lead to better HIV prevention messages and a more complete picture of the risks associated with HAI. In addition, very few papers have looked at factors associated with condom use during HAI among people who practice HAI. Obtaining a better understanding of these factors could allow better targeting of prevention messages.

The purpose of this study was to describe the prevalence and correlates of HAI among men and women with low socioeconomic status (SES) from 20 cities across the United States considering both individual and partner characteristics. In addition, factors associated with lack of condom use at last sex were assessed among those who had HAI.

Methods

Sample and Procedures

The National HIV Behavioral Surveillance (NHBS) system conducts annual surveys and HIV testing in populations at risk for HIV, including men who have sex with men (MSM), people who inject drugs, and heterosexuals at increased risk of HIV (15). In 2013, the third round of heterosexual data collection was conducted in 20 metropolitan statistical areas (MSA) across the United States, which were selected based on the high number of people living with AIDS (Atlanta, Georgia; Baltimore, Maryland; Boston, Massachusetts; Chicago, Illinois; Dallas, Texas; Denver, Colorado; Detroit, Michigan; Houston, Texas; Los Angeles, California; Miami, Florida; Nassau, New York; Newark, New Jersey; New Orleans, Louisiana; New York City, New York; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; San Diego, California; San Francisco, California; San Juan, Puerto Rico; Seattle, Washington; and Washington, District of Columbia). Participants were recruited by respondent-driven sampling (RDS), a type of chain-referral sampling. Respondent-driven sampling is initiated with a limited number of “seed” participants who are purposefully chosen through formative research. These individuals are then given 3–5 coupons to recruit other people they know into the study. Recruitment continues until the sample size is met or the end of the data collection period. The sampling and other methods used for the 2013 heterosexual NHBS sample have been described in more detail elsewhere (16).

Eligibility for the heterosexual cycle of NHBS was restricted to men and women between 18 and 60 years old, who had not previously participated in 2013, were residents of a study MSA, were able to complete the survey in English or Spanish, were able to provide informed consent, and reported having vaginal or anal sex in the past 12 months with an opposite sex partner. Based on results of a pilot study (17), the NHBS heterosexual cycle uses low socioeconomic status (SES) as a proxy for increased risk of acquiring HIV through heterosexual sex. Individuals could participate in the survey regardless of SES and injection drug use history. However, in order to obtain a sample that was at higher risk for HIV through heterosexual sex but not injection drug use, only people of low SES who had not injected drugs in the past year were allowed to recruit other participants. Low SES was defined as having no more than a high school education, or a household income (in 2012) at or below the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services poverty guidelines. The guidelines vary by the number of dependents in a household (18). For example, in 2012 a household of four was considered in poverty at or below an annual income of $23,050. Trained interviewers administered a computer-assisted personal interview that covered demographic information, sexual and drug use behaviors, and HIV testing history. Anonymous HIV testing was offered to all participants and was conducted following the interview. Participants received incentives for completing the interview and for the HIV test. The incentive format (cash or gift card) and amount varied by city based on formative assessment and local policy. A typical incentive included $25 for completing the interview, $25 for providing a specimen for HIV testing, and $10 for each participant successfully recruited. NHBS activities were approved by local institutional review boards in each participating city and the protocol was approved by the CDC (19, 20).

For this analysis, the sample was restricted to only men and women who completed the interview with valid responses as assessed by the interviewer, were of low SES, and did not report being HIV-positive. Self-reported HIV-positive participants were not included in the analysis because our area of interest for this paper was understanding behavior among heterosexuals who are not HIV-infected in order to tailor HIV primary prevention messages.

Measures

We looked at three outcomes; 1) HAI in the past year among all eligible respondents, 2) HAI at last sex among those reporting HAI in the previous 12 months, and 3) lack of condom use during HAI among those who had HAI at last sex. Participants were asked how many opposite-sex partners they had in the 12 months before interview and then, of these, the number with whom they had anal sex. Anyone who answered one or more was coded as having HAI in the 12 months before interview. Respondents were also asked detailed questions about their last sexual event with an opposite-sex partner, including whether they had anal sex, if so, whether they used a condom for anal sex, and if so, whether the condom was used for the entire act of anal sex. Anyone who reported having HAI during this event was coded as having HAI at last sex. Participants who reported that they did not use a condom and those who did but not for the entire time were coded as not using a condom at last HAI.

Several covariates were included in the models as predictors. These included demographic characteristics: race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic white, Hispanic, non-Hispanic other), age (18–24, 25–34, 35–49, 50–60), homeless in the past year, and annual household income in 2012 ($0–4,999, $5,000–9,999, $10,000–14,999, $15,000+). Past year behaviors were: injection drug use, binge drinking (5+ drinks in one sitting for men and 4+ drinks in one sitting for women), exchange sex (giving or receiving things like money or drugs in exchange for sex), 1 or more same-sex partners, testing for HIV, and multiple opposite-sex partners in the previous 12 months (>3 for men and >2 for women). The cut point for dichotomizing the number of sex partners was set at the median number of partners reported. Women and men with same-sex partners in the past year were included in our sample of heterosexuals, because, even though they are not strictly practicing heterosexual sex, they do still have opposite-sex partners and can be exposed to risk through this behavior. Participants were coded as having an STD in the past year if they reported being told by a health care professional that they had syphilis, gonorrhea, Chlamydia, or another STD. Characteristics of the last sexual event that were included in the model were: type of sex partner (main, casual, or exchange), use of drugs or alcohol at last sex, believing that the sex partner had ever injected drugs (definitely/probably versus definitely not/probably not), having a potentially HIV-discordant partner (either the respondent or their partner did not know their HIV status, or their partner was HIV-positive), and for women, believing the sex partner had ever had sex with a man (definitely/probably/don't know versus definitely not/probably not). The “don't know” category was included in this variable because there was a significant number of women who responded with don't know, even though this was not an explicit response option, and not knowing if one's partner had sex with other men is meaningful because it may suggest some level of risk.

Statistical Analysis

We ran separate models for each of the three outcomes of interest. Separate models were necessary because each model included a different sub-sample of the population. General estimating equation (GEE) models based on a Poisson distribution with robust standard errors were used to assess the association between each outcome and several demographic and individual and partner risk behaviors. In order to control for the study design, city and the recruiter's value for the outcome were included in the model as fixed effects and recruitment chain was treated as the cluster. An individual's network size, the number of men and women he/she knew, was included in the model to control for the variable probability of selection into the study. All the analyses, both bivariable and multivariable, controlled for study design. Adjusted prevalence ratios (aPR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated.

Results

During the 2013 data collection period, 12,517 people were screened, and 10,682 (85%) were eligible to participate. Of these, 10,543 (99%) gave consent, and completed the survey with valid responses as assessed by the interviewer. An additional 1,052 people were dropped from the analysis for either not meeting our definition of low SES (n = 869), self-reporting being HIV-positive (n = 184), or having missing information on HAI in the past year (n = 8), leaving a sample size of 9,491. The majority of the sample was non-Hispanic black (74%), 16% were Hispanic, 5% were non-Hispanic white, and 5% were of another race/ethnicity. The mean age was 38.2 years (standard deviation = 12.7). Over a quarter of the sample experienced homelessness in the previous year (29%) and had an annual income less than $5,000 (29%). Race (χ2 = 3437.2), age (F = 24.47), income (χ2 = 367.2), and experiencing homelessness (χ2 = 1085.5) all varied significantly by city (all p < 0.001). The proportion non-Hispanic black varied from 45% in San Diego to 95% in Atlanta (excluding Puerto Rico which was 99% Hispanic). The proportion non-Hispanic white varied from 0.4% in Chicago to 21% in Seattle, and the proportion Hispanic varied from 1% in Baltimore to 57% in Denver. The mean age ranged was 33 years in Los Angeles to 46 years in San Francisco. The prevalence of experiencing homelessness in the previous year ranged from 9% in Puerto Rico to 74% in San Francisco. The proportion with an income less than $5,000 varied from 18% in Chicago to 49% in Puerto Rico.

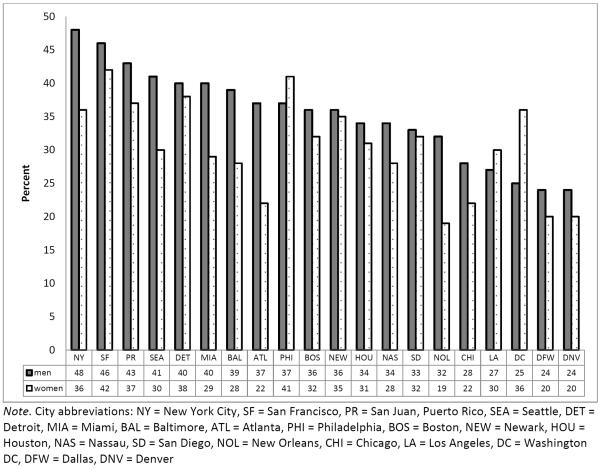

In this sample, significantly more men than women reported having HAI in the past year (35% vs. 30%, χ2 = 7.76, p=0.005). Across the 20 cities the prevalence among women varied from 20% to 42% (χ2 = 18.70, p=0.48) and among men the range was 24% to 48% (χ2 = 25.34, p=0.15; Figure 1). In bivariable analyses among men, the prevalence of AI was lower among non-Hispanic black men (33%) than Hispanic (39%), non-Hispanic white (42%), and other men (39%) (Table I, p=0.01). Among both men and women, there was a higher prevalence of HAI among those who were between 25 and 49 years old, had a lower income, or were homeless in the past year (Table I). In bivariable analysis, a lower percentage of men and women who had been tested for HIV in the past 12 months reported HAI than people who had not been tested (women p=0.004; men p=0.01). There was a higher prevalence of HAI among those who reported having been diagnosed with an STD in the past year compared to those who had not. There was no significant association between HIV status and HAI for men or women. HAI was also associated with several past-year risk behaviors, such as exchange sex, binge drinking, drug use, and having a same-sex partner. In multivariable analysis, all of these factors except testing for HIV in the past 12 months, income, and non-injection drug use, and among men, injection drug use, remained significant (Table I).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of heterosexual anal intercourse in the previous year among men and women by city, National HIV Behavioral Surveillance, Heterosexuals at increased risk for HIV infection, United States, 2013

Table I.

Prevalence and correlates of heterosexual anal intercourse in the past year among men and women, National HIV Behavioral Surveillance, Heterosexuals at increased risk for HIV infection, United States, 2013

| Women | Men | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| N | n | % | aPR (95% CI)a | N | n | % | aPR (95% CI)a | |

| Total | 4677 | 1414 | 30.2 | N=4570 | 4814 | 1688 | 35.1 | N=4709 |

|

| ||||||||

| Respondent demographic characteristics | ||||||||

| Raceb | ||||||||

| Black | 3503 | 1046 | 29.9 | Ref | 3533 | 1177 | 33.3 | Ref |

| Hispanic | 742 | 219 | 29.5 | 1.14 (0.97–1.34) | 819 | 323 | 39.4 | 1.49 (1.30–1.71) |

| White | 201 | 80 | 39.8 | 1.25 (1.05–1.49) | 238 | 99 | 41.6 | 1.34 (1.18–1.52) |

| Other | 229 | 69 | 30.1 | 0.97 (0.82–1.14) | 219 | 85 | 38.8 | 1.14 (0.93–1.40) |

| χ2 = 4.68 p = 0.20 | χ2 = 10.77 p = 0.01 | |||||||

| Age | ||||||||

| 18–24 | 958 | 240 | 25.1 | Ref | 970 | 265 | 27.3 | Ref |

| 25–34 | 1246 | 412 | 33.1 | 1.34 (1.16–1.55) | 908 | 334 | 36.8 | 1.20 (1.06–1.35) |

| 35–49 | 1469 | 511 | 34.8 | 1.31 (1.16–1.49) | 1575 | 638 | 40.5 | 1.23 (1.08–1.41) |

| 50–60 | 1004 | 251 | 25.0 | 1.03 (0.89–1.20) | 1361 | 451 | 33.1 | 1.04 (0.89–1.21) |

| χ2 = 19.31 p < 0.001 | χ2 = 17.47 p < 0.001 | |||||||

| Annual household income | ||||||||

| 0–4,999 | 1313 | 452 | 34.4 | 1438 | 566 | 39.4 | ||

| 5,000–9,999 | 1270 | 398 | 31.3 | 1145 | 401 | 35.0 | ||

| 10,000–14,999 | 1100 | 301 | 27.4 | 1112 | 358 | 32.2 | ||

| 15,000+ | 959 | 254 | 26.5 | 1077 | 352 | 32.7 | ||

| χ2 = 14.73 p = 0.002 | χ2 = 11.31 p = 0.01 | |||||||

| Experienced homelessness, 12mo | ||||||||

| Yes | 1131 | 472 | 41.7 | 1.09 (1.01–1.17) | 1600 | 719 | 44.9 | 1.12 (1.04–1.22) |

| No | 3546 | 942 | 26.6 | Ref | 3214 | 969 | 30.2 | Ref |

| χ2 = 19.20 p < 0.001 | χ2 = 20.22 p < 0.001 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| HIV testing/STD Status | ||||||||

| HIV test, 12 mo | ||||||||

| Yes | 1898 | 532 | 28.0 | 1661 | 542 | 32.6 | ||

| No | 2756 | 873 | 31.7 | 3118 | 1135 | 36.4 | ||

| χ2 = 8.25 p = 0.004 | χ2 = 6.63 p = 0.01 | |||||||

| HIV test result | ||||||||

| Positive | 56 | 20 | 35.7 | 69 | 25 | 36.2 | ||

| Negative | 4606 | 1393 | 30.2 | 4715 | 1657 | 35.1 | ||

| χ2 = 0.35 p = 0.56 | χ2 = 0.10 p = 0.75 | |||||||

| STD diagnosis, 12 mo | ||||||||

| Yes | 557 | 258 | 46.3 | 1.21 (1.12–1.30) | 250 | 123 | 49.2 | 1.18 (1.03–1.36) |

| No | 4108 | 1152 | 28.0 | Ref | 4555 | 1561 | 34.3 | Ref |

| χ2 = 21.57 p < 0.001 | χ2 = 12.78 p < 0.001 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Past year behaviors | ||||||||

| Multiple sex partnersc | ||||||||

| Yes | 2067 | 940 | 45.5 | 1.61 (1.45–1.78) | 2276 | 1113 | 48.9 | 1.60 (1.43–1.79) |

| No | 2610 | 474 | 18.2 | Ref | 2538 | 575 | 22.7 | Ref |

| χ2 = 29.19 p < 0.001 | χ2 = 29.67 p < 0.001 | |||||||

| Injection drug use | ||||||||

| Yes | 177 | 101 | 57.1 | 1.24 (1.08–1.42) | 297 | 152 | 51.2 | |

| No | 4500 | 1313 | 29.2 | Ref | 4515 | 1536 | 34.0 | |

| χ2 = 15.04 p < 0.001 | χ2 = 12.19 p < 0.001 | |||||||

| Non-injection drug use | ||||||||

| Yes | 2706 | 971 | 35.9 | 3330 | 1271 | 38.2 | ||

| No | 1971 | 443 | 22.5 | 1483 | 416 | 28.1 | ||

| χ2 = 26.91 p < 0.001 | χ2 = 18.06 p < 0.001 | |||||||

| Exchange Sex | ||||||||

| Yes | 1475 | 739 | 50.1 | 1.43 (1.27–1.61) | 1746 | 945 | 54.1 | 1.67 (1.47–1.90) |

| No | 3201 | 674 | 21.1 | Ref | 3065 | 741 | 24.2 | Ref |

| χ2 = 28.35 p < 0.001 | χ2 = 26.23 p < 0.001 | |||||||

| Binge drinking | ||||||||

| Yes | 3198 | 1107 | 34.6 | 1.33 (1.20–1.47) | 3451 | 1342 | 38.9 | 1.30 (1.17–1.44) |

| No | 1476 | 307 | 20.8 | Ref | 1361 | 345 | 25.4 | Ref |

| χ2 = 23.71 p < 0.001 | χ2 = 20.63 p < 0.001 | |||||||

| Same-sex partner | ||||||||

| Yes | 982 | 547 | 55.7 | 1.53 (1.36–1.72) | 293 | 228 | 77.8 | 1.55 (1.41–1.72) |

| No | 3693 | 866 | 23.5 | Ref | 4516 | 1457 | 32.3 | Ref |

| χ2 = 26.58 p < 0.001 | χ2 = 18.09 p < 0.001 | |||||||

Note: aPR = adjusted prevalence ratio, CI = confidence interval, χ2 p-value based on type 3 global test of significance in bivariable GEE model that controlled for factors related to study design

model controlled for factors related to study design (city, recruiter's value for the outcome, network size) and clustered on recruitment chain

Race/ethnicity groups are mutually exclusive; Hispanic can be of any race

multiple sex partners = 3+ for women and 4+ for men

Typically, HAI was not practiced with all of a respondent's sex partners. Among people who had HAI in the past year and had two or more partners, a small percentage had HAI with all their partners (women: 11% (n=126); men: 17% (n=262); data not shown in table). In order to determine what partnership characteristics may be associated with having HAI with that partner, a further analysis was conducted looking at factors associated with having HAI at last sex among those who had HAI in the past year. Men (35%) and women (33%) who had HAI in the past year were equally likely to have HAI during their last sex act (χ2 = 0.55, p=0.46). In multivariable analysis among women, characteristics of the partner that were associated with having HAI included being potentially HIV discordant (aPR=1.58, CI=1.26–1.97), ever injecting drugs (aPR=1.28, CI=1.03–1.61), and being an exchange partner versus a main partner (aPR=1.30, CI=1.08–1.57; Table II). These same characteristics were associated with HAI among men in multivariable analysis: having a potentially HIV-discordant partner (aPR=1.28, CI=1.07–1.55), a partner who ever injected drugs (aPR=1.25, CI=1.08–1.46), and having an exchange partner versus a main partner (aPR=1.62, CI=1.33–1.96; Table II). Race/ethnicity was included in both models, but there were no significant associations.

Table II.

Prevalence and correlates of heterosexual anal intercourse (HAI) at last sex and condom use among men and women, National HIV Behavioral Surveillance, Heterosexuals at increased risk for HIV infection, United States, 2013

| HAI at last sex among those who had HAI in the past year | Condomless HAI among those who had HAI at last sex | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| N | n | % | aPR (95% CI) | n | % | aPR (95% CI) | |

| Women | 1414 | 470 | 33.2 | N=1332a | 438 | 93.2 | N=463a |

|

| |||||||

| Last sex partner | |||||||

| Partner type | |||||||

| Main | 741 | 199 | 26.9 | Ref | 182 | 91.5 | |

| Casual | 234 | 73 | 31.2 | 0.95 (0.75–1.20) | 69 | 94.5 | |

| Exchange | 438 | 198 | 45.2 | 1.30 (1.08–1.57) | 187 | 94.4 | |

| χ2 = 16.09, p < 0.001 | χ2 = 0.84, p = 0.66 | ||||||

| Potentially discordant partnerb | |||||||

| Yes | 974 | 372 | 38.2c | 1.58 (1.26–1.97) | 354 | 95.2 | 1.10 (1.02–1.19) |

| No | 440 | 98 | 22.3 | Ref | 84 | 85.7 | Ref |

| χ2 = 15.23, p < 0.001 | χ2 = 7.17, p = 0.007 | ||||||

| Partner ever injected drugs | |||||||

| Yes | 302 | 136 | 45.0 | 1.28 (1.03–1.61) | 130 | 95.6 | |

| No | 1051 | 311 | 29.6 | Ref | 286 | 92.0 | |

| χ2 = 7.90, p = 0.005 | χ2 = 2.25, p = 0.13 | ||||||

| Partner ever had sex with a man | |||||||

| Yes | 359 | 155 | 43.2 | 153 | 98.7 | 1.06 (1.02–1.11) | |

| No | 1054 | 314 | 29.8 | 284 | 90.5 | Ref | |

| χ2 = 7.31, p = 0.007 | χ2 = 12.37, p < 0.001 | ||||||

| Last sex event | |||||||

| Respondent used alcohol/drugs before/during sex | |||||||

| Yes | 780 | 285 | 36.5 | 265 | 93.0 | ||

| No | 634 | 185 | 29.2 | 173 | 93.5 | ||

| χ2 = 4.86, p = 0.03 | χ2 = 0.10, p = 0.75 | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| Men | 1687 | 591 | 35.0 | N=1593c | 514 | 87.0 | N=569a |

|

| |||||||

| Last sex partner | |||||||

| Partner type | |||||||

| Main | 717 | 179 | 25.0 | Ref | 158 | 88.3 | Ref |

| Casual | 474 | 157 | 33.1 | 1.19 (0.99–1.44) | 126 | 80.3 | 0.87 (0.78–0.96) |

| Exchange | 496 | 255 | 51.4 | 1.62 (1.33–1.96) | 230 | 90.2 | 0.92 (0.84–1.01) |

| χ2 = 20.75, p < 0.001 | χ2 = 5.31, p = 0.07 | ||||||

| Potentially discordant partnerd | |||||||

| Yes | 1207 | 472 | 39.1 | 1.28 (1.07–1.55) | 430 | 91.1 | 1.21 (1.10–1.32) |

| No | 480 | 119 | 24.8 | Ref | 84 | 70.6 | Ref |

| χ2 = 14.93, p < 0.001 | χ2 = 10.19, p = 0.001 | ||||||

| Partner ever injected drugs | |||||||

| Yes | 366 | 181 | 49.5 | 1.25 (1.08–1.46) | 173 | 95.6 | 1.11 (1.03–1.19) |

| No | 1267 | 395 | 31.2 | Ref | 328 | 83.0 | Ref |

| χ2 = 11.27, p < 0.001 | χ2 = 6.62, p = 0.01 | ||||||

| Last sex event | |||||||

| Respondent used alcohol/drugs before/during sex | |||||||

| Yes | 1116 | 414 | 37.1 | 374 | 90.3 | 1.11 (1.01–1.23) | |

| No | 569 | 177 | 31.1 | 140 | 79.1 | Ref | |

| χ2 = 3.01, p = 0.08 | χ2 = 6.06, p = 0.01 | ||||||

Note: aPR = adjusted prevalence ratio, CI = confidence interval, p-value based on type 3 global test of significance in bivariable GEE model that controlled for factors related to study design.

model controlled for race/ethnicity and factors related to study design (city, recruiter's value for the outcome, network size) and clustered on recruitment chain

potentially discordant partner = the respondent or partner is unaware of their HIV status or the partner is HIV-positive

model controlled for race, homelessness in the past year, annual household income and factors related to study design (city, recruiter's value for the outcome, network size, and clustered on recruitment chain

Finally, we looked at factors associated with not using a condom at last HAI among those who had HAI. Women (93%) were significantly more likely to not use a condom at last HAI compared to men (87%; χ2 = 4.48, p=0.03). In multivariable analysis among women who had HAI at last sex, not using a condom was associated with having a partner who was potentially HIV discordant (aPR=1.10, CI=1.02–1.19) and had sex with a man in his lifetime (aPR=1.06, CI=1.02–1.11; Table II). Among men who had HAI at last sex, not using a condom was associated with the respondent using drugs or alcohol before or during sex (aPR=1.11, CI=1.01–1.23), the partner being potentially HIV discordant (aPR=1.21, CI=1.10–1.32), or the partner ever injecting drugs in her lifetime (aPR=1.11, CI=1.03–1.19), and inversely associated with the partner being a casual partner (aPR=0.87, CI=0.78–0.96; Table II). Condom use was not associated with race/ethnicity among men or women. Condom use during HAI was less common than condom use during vaginal intercourse (VI). Among those who had VI at last sex, 85% of women and 80% of men did not use a condom (men vs women: χ2 = 15.45, p<0.001). Among men and women who had VI at last sex, condom use during VI was less common if they also had HAI during the same event. Among participants who only had VI, 78% of men and 84% of women did not use a condom, compared to 89% of men and 95% of women who had both VI and HAI (men: χ2 = 17.20, p<0.001; women: χ2 = 15.51, p<0.001). Overall, 10% of women (n=454) and 12% of men (n=559) had both HAI and VI at last sex. Of these people, the majority did not use a condom for either act (men: 86%, women: 92%) and only 4% of women and 10% of men used a condom for both (data not shown in table).

Discussion

The prevalence of HAI was high in our sample with about one-third of men and women engaging in this behavior during the 12 months before the interview. This is comparable to the HAI prevalence seen in other studies – 39% in the past year among STI clinic attendees (21), 32% in the past 6 months among women at high risk of HIV (12). Among those who had HAI in the past year, about one-third of men and women had HAI at last sex, furthermore, condom use at last sex was very rare, and even lower with high-risk partners such as partners with discordant status, who reported male-male sex (among women) or injection drug use (among men). Low condom use rates have been noted in other work as well (5, 6, 14), but correlates of condom use during HAI have not been as well studied. Our analysis demonstrated in a sample of men and women from across the U.S. that condomless HAI was associated with other factors that could increase a person's risk of acquiring HIV.

In our sample, white non-Hispanic women were more likely to report HAI than black non-Hispanic women. Among men, Hispanic and white non-Hispanic men were more likely to report HAI than black non-Hispanic men. Others have found a similar pattern with black men and women being the least likely to report HAI (7, 11, 22, 23), while others have found no significant difference by race/ethnicity (8, 24). However, we did not find any differences by race/ethnicity in the prevalence of having HAI at last sex, or not using a condom at last HAI. Few studies have looked at correlates of condom use during HAI, but two have found that black men and women were more likely to use a condom during HAI than white men and women (22, 23). HAI was associated with experiencing homelessness in the past year among both men and women. This finding supports other work that has found the same association (6, 24).

As has been shown in previous work (6, 7, 9, 11), we found that past HAI was associated with other higher risk behaviors, including having multiple sex partners, injection drug use, exchange sex, and binge drinking, as well as having same-sex partners. Men and women who reported HAI were also more likely to report having an STI in the past year, further increasing their risk of HIV acquisition. Given this combination of high-risk behaviors, especially having multiple sex partners, these heterosexuals should be re-tested annually for HIV according to CDC guidelines (25); however, in our sample the inverse relationship between risk and HIV testing was found. One study among youth in Baltimore found the same inverse relationship among male participants, but not female participants (10).

Among those who reported HAI in the past year, HAI at last sex was associated with having a higher-risk partner for both men and women – potentially HIV discordant, ever injected drugs, and an exchange partner. Given that almost all the HAI was unprotected, it is concerning that the partners tended to be at high risk with a potentially higher HIV prevalence. Finally, we examined factors associated with not using a condom at last HAI among those who had HAI at last sex, although condom non-use was extremely common, especially for women (93%). Women who did not use a condom were more likely to have a higher-risk partner – potentially HIV discordant and ever had sex with another man. There was no association with partner type or drug or alcohol use by the woman. Among men, condom non-use was also associated with higher-risk partners – HIV discordant and ever injected drugs. In addition, it was also positively associated with the man using drugs or alcohol at last sex, and inversely associated with having a casual partner compared to a main partner. Few papers have looked at factors associated with condom use during HAI among people who had HAI. This may be partly due to the very low rates of condom use during HAI, making it hard to detect differences, such as in one study among female drug users that found no significant associations between condom use and individual or partner characteristics (14). One study found, among men and women attending an STD clinic, that consistent condom use during HAI over the previous 3 months was associated with having a new partner, having a non-main partner, and the respondent or partner never being high during sex (21). A daily-diary study among adolescent women found that condom use was associated with feeling less in love and using a condom during vaginal intercourse that same day, but there was no association with drug or alcohol use (26), similar to our findings among women.

There are several limitations in this study including a potential for under-reporting of socially undesirable information, i.e. HAI. This is of particular concern in this study due to the face-to-face method used for data collection. However, the prevalence of HAI was similar to other studies that collected data by other methods (12, 21). The anonymous nature of NHBS also increases privacy and, therefore, may foster candid reporting of behaviors (27, 28). We are also missing some key pieces of information that would aide in our understanding of this behavior, such as data on intimate partner violence, which has been shown to be associated with HAI (11, 23) and condom use during HAI (23), and information on the frequency of HAI and the order of acts during a sexual encounter (29). Future studies would benefit from the inclusion of this information and use of an a priori-conceptual model that includes all variables potentially associated with HAI. In addition, the sample only included people of low SES, so our findings are not generalizable to the general population. However, this population is at higher risk for acquisition of HIV, so it is important to understand the prevalence and correlates of HAI in this population.

This study provided further insight into HAI among a high-risk population. It is important to understand the correlates of HAI in order to better tailor prevention messages to heterosexuals at risk of HIV. HAI is a common practice and condoms are rarely used, but often people are not aware that HAI presents a risk for HIV/STI acquisition (30), which highlights the importance of discussing HAI and its risks. Clinicians and community-out-reach workers should include discussions of HAI in risk assessments and counseling messages for heterosexuals at high risk for HIV infection as well as stress the importance of annual HIV testing among those who report high-risk behaviors (25).

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was funded by a cooperative agreement between the Health Departments of the 20 study U.S. cities (Atlanta, Georgia; Baltimore, Maryland; Boston, Massachusetts; Chicago, Illinois; Dallas, Texas; Denver, Colorado; Detroit, Michigan; Houston, Texas; Los Angeles, California; Miami, Florida; Nassau, New York; Newark, New Jersey; New Orleans, Louisiana; New York City, New York; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; San Diego, California; San Francisco, California; San Juan, Puerto Rico; Seattle, Washington; and Washington, District of Columbia) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Funding Opportunity Announcement #PS11-001).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Compliance with Ethical Standards All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- 1.Chandra A, Mosher WD, Copen C, Sionean C. Sexual behavior, sexual attraction, and sexual identity in the United States: data from the 2006–2008 National Survey of Family Growth. Natl Health Stat Report. 2011(36):1–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aral SO, Patel DA, Holmes KK, Foxman B. Temporal trends in sexual behaviors and sexually transmitted disease history among 18- to 39-year-old Seattle, Washington, residents: results of random digit-dial surveys. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32(11):710–7. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000175370.08709.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Satterwhite CL, Kamb ML, Metcalf C, et al. Changes in sexual behavior and STD prevalence among heterosexual STD clinic attendees: 1993–1995 versus 1999–2000. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34(10):815–9. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31805c751d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baggaley RF, White RG, Boily MC. HIV transmission risk through anal intercourse: systematic review, meta-analysis and implications for HIV prevention. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39(4):1048–63. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koblin BA, Hoover DR, Xu G, et al. Correlates of anal intercourse vary by partner type among substance-using women: baseline data from the UNITY study. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(1):132–40. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9440-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hess KL, Reynolds GL, Fisher DG. Heterosexual anal intercourse among men in Long Beach, California. J Sex Res. 2014;51(8):874–81. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2013.809512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Javanbakht M, Guerry S, Gorbach PM, et al. Prevalence and correlates of heterosexual anal intercourse among clients attending public sexually transmitted disease clinics in Los Angeles County. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37(6):369–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gorbach PM, Manhart LE, Hess KL, Stoner BP, Martin DH, Holmes KK. Anal intercourse among young heterosexuals in three sexually transmitted disease clinics in the United States. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36(4):193–8. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181901ccf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calsyn DA, Hatch-Maillette MA, Meade CS, Tross S, Campbell AN, Beadnell B. Gender differences in heterosexual anal sex practices among women and men in substance abuse treatment. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(7):2450–8. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0387-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hebert LE, Lilleston PS, Jennings JM, Sherman SG. Individual, partner, and partnership level correlates of anal sex among youth in Baltimore city. Arch Sex Behav. 2015;44(3):619–29. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0431-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ibanez GE, Kurtz SP, Surratt HL, Inciardi JA. Correlates of heterosexual anal intercourse among substance-using club-goers. Arch Sex Behav. 2010;39(4):959–67. doi: 10.1007/s10508-010-9606-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gross M, Holte SE, Marmor M, Mwatha A, Koblin BA, Mayer KH. Anal sex among HIV-seronegative women at high risk of HIV exposure. The HIVNET Vaccine Preparedness Study 2 Protocol Team. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;24(4):393–8. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200008010-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baldwin JI, Baldwin JD. Heterosexual anal intercourse: an understudied, high-risk sexual behavior. Arch Sex Behav. 2000;29(4):357–73. doi: 10.1023/a:1001918504344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mackesy-Amiti ME, McKirnan DJ, Ouellet LJ. Relationship characteristics associated with anal sex among female drug users. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37(6):346–51. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181c71d61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gallagher KM, Sullivan PS, Lansky A, Onorato IM. Behavioral surveillance among people at risk for HIV infection in the U.S.: the National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System. Public Health Rep. 2007;122(Suppl 1):32–8. doi: 10.1177/00333549071220S106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sionean C, Le BC, Hageman K, et al. HIV Risk, prevention, and testing behaviors among heterosexuals at increased risk for HIV infection--National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System, 21 U.S. cities, 2010. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2014;63(14):1–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dinenno EA, Oster AM, Sionean C, Denning P, Lansky A. Piloting a system for behavioral surveillance among heterosexuals at increased risk of HIV in the United States. Open AIDS J. 2012;6:169–76. doi: 10.2174/1874613601206010169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Annual Update of the HHS Poverty Guidelines. Federal Register [Internet] 2015 Dec 1;77(17):4034–5. 2012. Available from: http://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty/12fedreg.shtml. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Human Research Protections 2010. 2015 Sep 21; Available from: http://aops-mas-iis.cdc.gov/Policy/Doc/policy556.pdf.

- 20.Code of Federal Regulations: Title 45 Public Welfare Part 46 Protections of Human Subjects 2009. 2015 Sep 21; Available from: http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/policy/ohrpregulations.pdf. [PubMed]

- 21.Tian LH, Peterman TA, Tao G, et al. Heterosexual anal sex activity in the year after an STD clinic visit. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35(11):905–9. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318181294b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leichliter JS, Chandra A, Liddon N, Fenton KA, Aral SO. Prevalence and correlates of heterosexual anal and oral sex in adolescents and adults in the United States. J Infect Dis. 2007;196(12):1852–9. doi: 10.1086/522867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hess KL, Javanbakht M, Brown JM, Weiss RE, Hsu P, Gorbach PM. Intimate partner violence and anal intercourse in young adult heterosexual relationships. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2013;45(1):6–12. doi: 10.1363/4500613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jenness SM, Begier EM, Neaigus A, Murrill CS, Wendel T, Hagan H. Unprotected anal intercourse and sexually transmitted diseases in high-risk heterosexual women. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(4):745–50. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.181883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-14):1–17. quiz 1CE1-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hensel DJ, Fortenberry JD, Orr DP. Factors associated with event level anal sex and condom use during anal sex among adolescent women. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46(3):232–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tourangeau R, Yan T. Sensitive questions in surveys. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133(5):859–83. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.5.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ong AD, Weiss DJ. The impact of anonymity of responses to sensitive questions. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2000;30(8):1691–708. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gorbach PM, Pines H, Javanbakht M, et al. Order of orifices: sequence of condom use and ejaculation by orifice during anal intercourse among women: implications for HIV transmission. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;67(4):424–9. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stahlman S, Hirz AE, Stirland A, Guerry S, Gorbach P, Javanbakht M. Contextual factors surrounding anal intercourse in women: Implications for sexually transmitted infection/HIV prevention. Sex Transm Dis. 2015;42(7):364–8. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]