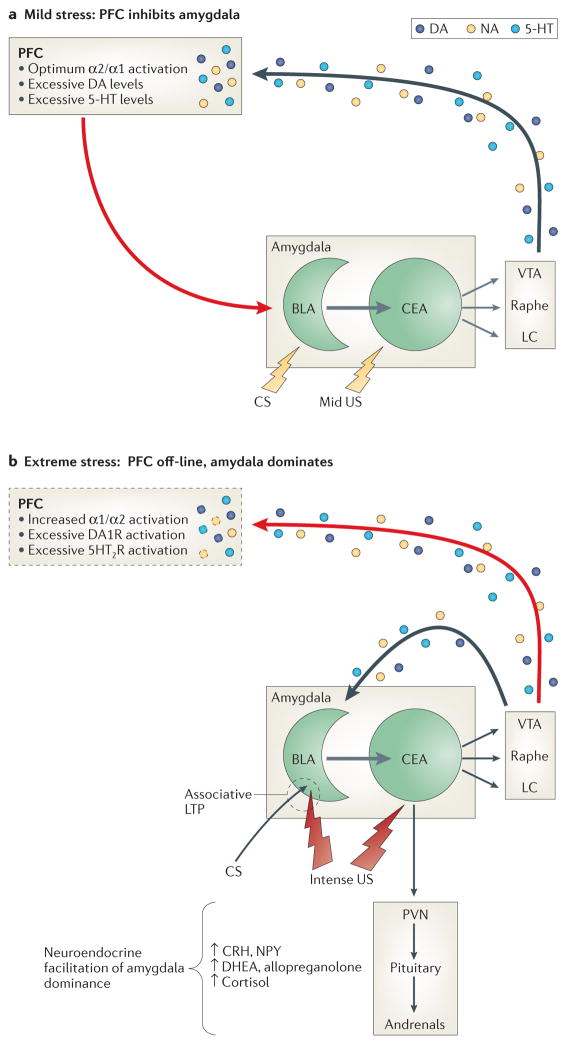

Figure 4. Putative brain-state relevant to PTSD.

Panel A (resilience): The response of either a) previously nontraumatized individuals exposed to mild or moderately arousing unconditioned threat stimuli, b) resilient individuals who are resistant to the arousing effects of more extreme unconditioned threat, or c) individuals with PTSD after undergoing extinction and recovery so that conditioned threat stimuli are no longer highly arousing. Panel B (risk): The response of a) previously nontraumatized individuals exposed to unconditioned threat that is highly arousing, b) individuals with PTSD who are re-exposed to trauma-related cues (conditioned threat) prior to extinction and recovery, or c) individuals with PTSD who are resistant to recovery.

A. Neuromodulation contributing to relative prefrontal cortical dominance (resilience). Mild to moderately arousing sensory stimuli activate the central nucleus (CE) of the amygdala, which projects both directly and indirectly to brainstem monoaminergic cell body regions to activate mesocorticolimbic dopamine (DA) pathways emanating from the ventral tegmental area (VTA), as well as more widely disseminating NE and serotonergic (5-HT) pathways emanating from the locus coeruleus (LC) and median/dorsal raphe nuclei, respectively.151 In the prefrontal cortex (PFC), the resulting mild to moderate increases in synaptic levels of these monoamines engage high-affinity (e.g., noradrenergic alpha-2) receptors to enhance working memory152 and activate glutamatergic pyramidal output neurons that project back to the amygdala. There, glutamatergic activation of GABAergic interneurons in the basolateral (BLA) and/or intercalated nuclei suppresses associative learning and inhibits excitatory BLA pyramidal cell projections to the CE and the expression of the species-specific defense response (see below).153

B. Neuromodulation contributing to relative amygdala dominance (risk). Strongly arousing unconditioned threat stimuli (due to objective threat characteristics or an individual’s increased sensitivity to objective threat) or conditioned threat stimuli in persons with PTSD activate the amygdala to a greater degree, which in turn excites brainstem mesocorticolimbic monoaminergic neurons more vigorously57, 151—a process likely facilitated by reductions in GABAergic neurotransmission within the amygdala.154, 155 In the PFC, higher synaptic levels of these monoamines engage low-affinity noradrenergic alpha-1, as well as DA1 and 5HT2 receptors, resulting in working memory impairment and a reduction in PFC inhibition of amygdala.152 Consequent lifting of the PFC “brake” reduces GABAergic tone within the BLA and intercalated nuclei of the amygdala to enable associative pairing of unconditioned threat stimuli (US) and convergent contextual stimuli (CS) or later reconsolidation of conditioned stimuli, as well as activation of the species-specific defense response (SSDR(, which includes increases in blood pressure and heart rate, HPA axis activation, engagement in reflexive defensive behaviors (fight, flight, freezing), and restriction of high-level information processing to enable efficient focus on survival-relevant phenomena. Direct catecholamine effects in the amygdala also facilitate defensive responding: activation of D1 receptors on PFC projection neuron terminals inhibits glutamate activation of GABAergic interneurons, whereas activation of post-synaptic D2 receptors on BLA to CE pyramidal projection neurons increases their excitation by convergent US-CS inputs, as well as adventitious sensory stimuli. This likely facilitates or maintains associative fear conditioning and may contribute to generalization of fear.156 In contrast, neuronal activity in the BLA is generally suppressed by NE alpha-2 and alpha-1 receptor stimulation, though the latter effect, mediated by enhanced terminal release of GABA, is reduced by chronic stress.157 In contrast NE beta-receptor activation is excitatory and enhances US-CS pairing.158