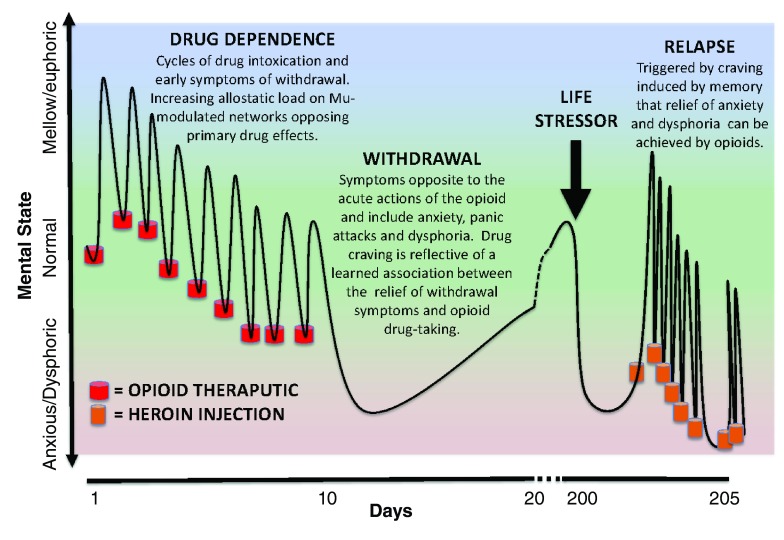

Figure 2. Laura’s pathway to heroin addiction.

Here we provide a hypothetical scenario of how learned association of relief of aversive states could lead to the development of addiction and the key role of opioid dependence. Let us consider a disappointed teenager (Laura) who sprained her ankle during tryouts for the cheerleading team and was rejected, not making the squad. Knowing that opioids will alleviate the pain caused by the sprained ankle, Laura takes an opioid analgesic pill she knows is in the bathroom medicine cabinet, left over from her older brother’s prescription for a wisdom tooth extraction. The opioid pill takes away Laura’s pain from the sprained ankle and makes her feel relaxed (mellow and with elevated mood). She is less bothered about the tryout rejection while under the influence of the opioid. The next day, Laura decides to take another pill as the drug effects have worn off and both the ankle (physical) pain and the (psychological) pain of rejection have returned and are just as bad as the day before. The taking of the opioid medication again relieves the physical pain and takes her mind off her failure. Over the next 10 days, the drug taking cycle continues, but each day the pain-relieving effects are less (development of tolerance) and she develops a modest anxiogenic state prior to taking the drug each day (early signs of withdrawal). As the pain from the ankle sprain subsides, the association of drug taking becomes the relief of the anxious and dysphoric states that emerge as the drug wears off. On day 10, the supply of drugs from the medicine cabinet is exhausted and withdrawal sets in. Drug seeking would be a consequence during this withdrawal phase given the learned association that the aversive symptoms she is experiencing could be effectively relieved by taking the opioid (negative reinforcement). Although unlikely, given the ready access to illicit opioids throughout society, let’s assume that at this point in Laura’s life, she doesn’t actively seek out prescription or other opioids. The teen goes through physical withdrawal (over days) with protracted mood disturbances accompanied by drug craving that is triggered by memories that she could relieve dysphoric states by taking opioids. She doesn’t continue to seek opioids at this stage because the pain of rejection has dissipated and she is now engaged with other activities in her peer group. Over a year later, her boyfriend breaks up with her, her grades are not stellar, and she may not get accepted to the colleges she wants to go to. Laura becomes extremely stressed and feels unable to cope. The emergence of these negative symptoms initiates a craving for opioids that is triggered by learned associative memories. At this point in her life, she has the resources to access heroin and relapses. Laura’s relapse reinforces the associative memories that aversive states are relieved by opioids and the foundation for further addictive behaviors is strengthened. In this example, drug dependence and withdrawal contributes to the addiction vulnerability and the learned associative memories are of the negative reinforcement provided by opioid relief of anxiogenic and dysphoric states, and are triggered by a different stressor.