Abstract

Here we report the synthesis and characterization of a family of photolabile nitroveratryl-based surfactants that form different types of supramolecular structures depending on the alkyl chain lengths ranging from eight to twelve carbon atoms. By incorporating a photocleavable α-methyl-o-nitroveratryl moiety, the surfactants can be degraded, along with their corresponding supramolecular structures, by light irradiation in a controlled manner. The self-assembly of the amphiphilic surfactants was characterized by conductometry to determine the critical concentration for the formation of the supramolecular structures, transmission electron microscopy to determine the size and shape of the supramolecular structures, and dynamic light scattering (DLS) to determine the hydrodynamic diameter of the structures in aqueous solutions. The photodegradation of the surfactants and the supramolecular structures was confirmed using UV-Vis spectroscopy, mass spectrometry, and DLS. This surfactant family could be potentially useful in drug delivery, organic synthesis, and other applications.

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Surfactants are of broad interest to the scientific community because of their utility in the generation of templated self-assembly nano- and micro-structures.1-5 They are also desirable in organic synthesis because the nano- and micro-structures formed by surfactants can be used as a reaction vessel to allow for compartmentalization of the reactions.6-10 Furthermore, they are commonly used in many biological applications as surface-acting reagents for extracting and solubilizing proteins from cell or tissue lysates,11-13 or as drug delivery containers for water insoluble drugs or gene delivery containers.14-18 Through the addition of stimuli sensitive moieties into the molecular structure of the surfactant, a responsive surfactant can be created that allows for the external control of its properties in a predicted manner.19-23 The resulting change of the surfactant structure will affect not only the self-assembly behaviors by changing the packing parameters in aqueous solutions, but also the properties such as viscosity, foam, and emulsion stability.23 Stimuli-cleavable surfactants can be significantly efficient for the synthesis of templated mesoporous structures4 or semiconductor nanoparticles (NPs).24 When non-stimuli cleavable surfactants are used, calcinations, solvent washing, and centrifugation, or an additional acid extraction step is commonly used to remove the typical surfactant molecules.25 Moreover, because a small amount of ionic surfactant molecules can suppress the mass spectrometry (MS) signals, stimuli-labile surfactants are especially attractive because it allows for the extraction of proteins from cell or tissue that can be use for further MS analysis.11 Therefore, the development of stimuli-labile surfactant molecules is highly desirable for applications in various chemical and biological fields. These stimuli can range from a change in the solution pH,26-28 ionic strength, redox environment,29 to light20, 22, 23, 30, 31 and temperature.22, 29, 32

Light as an external stimulus provides significant advantages over other stimuli as it allows for a noninvasive on-command control trigger of the surfactants.33 However, it is challenging to incorporate an efficient photocleavable group into a surfactant molecule. Two approaches can be used to establish photo-responsive surfactant systems: a photo-active component can be added into the surfactant solution or incorporated into the molecular structure of the surfactant.30 When a photo-active component such as diazosulfonates34 is incorporated into the surfactant's molecular structure, they can be fragmented using UV irradiation.22, 35 However, many surfactants with a photo-sensitive group undergo conformational isomerization when irradiated by UV light without the actual fragmentation of the surfactant.20, 33, 36-38

Herein, we report a new series of photolabile surfactant molecules that form different types of supramolecular structures depending on the alkyl chain length by incorporating a photolabile α-methyl-o-nitroveratryl (ONV) moiety in the surfactants, which can be fragmented39-45 with increased photolysis rates compared to the parent o-nitrobenzyl linker39 along with their corresponding supramolecular structures in a controlled manner using light irradiation. The key to the properties of the surfactants is an ONV photolabile linker between a hydrophilic head and a hydrophobic tail with different hydrophobic alkyl chain lengths (8, 10 and 12 carbons) (Figure 1). These light sensitive surfactants were studied by transmission electron microscopy (TEM), conductometry, dynamic light scattering (DLS), UV-Vis spectroscopy, and MS for their self assembly and photo degradation behaviors. They are prepared by using a general synthetic route that can be easily adapted for the synthesis of other desired alkyl lengths (Scheme 1). Following the same overall synthetic procedure and changing the alkyl chain could potentially generate many variations of surfactants with different assembly behaviors and properties.

Figure 1.

Schematic structure of the surfactants consisting of an ONV photolabile linker with tunable alky chains.

Scheme 1.

Synthetic procedure for photodegradable surfactant (n= 6, 8, 10)

Experimental Section

Materials

All chemicals and reagents were used as received without further purification unless otherwise noted. Octylamine, triethylamine (Et3N), decylamine, dodecylamine, N-ethyldiisopropylamine (EDIPA), piperidine, 1,4-butanesultone, and anhydrous N,N-dimethylforamide (DMF) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Milwaukee, WI, USA). N,N,N′,N′-Tetramethyl-O-(1H-benzotriazol-1-yl) uronium hexafluorophosphate (HBTU) was obtained from TCI America (Portland, OR, USA). Fmoc-photolabile linker was purchased from Advanced Chemtech (Louisville, KY, USA).

Characterization

1H-NMR spectra were recorded on a Hermes-Varian Mercury Plus 300 (300 MHz) spectrometer at room temperature. Chemical shifts were recorded in parts per million (ppm) using residual solvent peaks as internal references [MeOH-d4 δ: 4.5 (1H) and DMSO-d6 δ: 2.5]. Electro spray ionization mass spectra for the synthesized ligand molecules were obtained using a Waters (Micromass) LCT® mass spectrometer (Waters, Beverly, MA) similarly as described previously.46 High-resolution Fourier transformed ion cyclotron resonance (FT-ICR) mass spectra before and after UV irradiation were obtained on a 7 T LTQ/FT (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA), similarly as described in our previous publication.11 DLS was carried out using a Malvern Zetasizer Nano. All DLS measurements of individual samples were performed three times after 120 sec equilibration.

Synthetic Procedures

Fmoc-ONV-CH2 (CH2)10 CH3 (1, n=10)

To a solution of Fmoc-ONV-COOH (300 mg, 0.57 mmol) and HBTU (262.8 mg, 0.69 mmol) in 3.5 mL of anhydrous DMF, EDIPA (149.1 mg, 1.15 mmol) was added drop wise. The solution was cooled on ice and added to a solution of dodecylamine in 0.5 mL of EtOH that was also cooled on ice. After stirring for 30 min at 0 °C, the mixture was stirred overnight at room temperature. The resulting precipitate was filtered and washed with DMF followed by in vacuo drying. Product 1 (n=10) (average yield = 68.1%) was obtained as an amorphous white powder. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6), as shown in Figure S1, δ ppm 8.08 (1H, -NH-Fmoc), 7.24-7.46, 7.63-7.65, and 7.86-7.89 (10H, Ar-H), 7.80 (1H,t, -NHCO), 5.20 (1H, m, -CH(CH3)NH), 4.27 (2H,CH2O), 4.17 (1H,CH2CH-Fmoc) 4.03 (2H, t, OCH2CH2), 3.86 (3H, s, CH3O), 3.02 (2H, td, CONH-CH2), 2.22 (2H, m, CH2CONH), 1.94 (2H, m, OCH2CH2CH2CONH), 1.40-1.42 (5H, CH3CHNH + CONHCH2CH2(CH2)9CH3), 1.2-1.36 (18H, m, CH2(CH2)9CH3), 0.84 (3H, t, CH2(CH2)9CH3).

Fmoc-ONV-CH2 (CH2)8 CH3 (1, n=8)

To a solution of Fmoc-ONV-COOH (300 mg, 0.57 mmol) and HBTU (262.8 mg, 0.69 mmol) in 3.5 mL of anhydrous DMF, EDIPA (149.1 mg, 1.15 mmol) was added drop wise. The solution was cooled on ice and added to a solution of decylamine in 0.5 mL of EtOH that was also cooled on ice. After stirring for 30 min at 0 °C, the mixture was stirred overnight at room temperature. The resulting precipitate was filtered and washed with DMF (two times) followed by in vacuo drying. Product 1 (n=8) (average yield = 58.3%) was obtained as an amorphous white powder. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6), shown in Figure S2, δ ppm 8.07 (1H, -NH-Fmoc), 7.24-7.46, 7.63-7.65, and 7.86-7.89 (10H, Ar-H), 7.80 (1H,t, -NHCO), 5.20 (1H, m, -CH(CH3)NH), 4.27 (2H,CH2O), 4.17 (1H,CH2CH-Fmoc) 4.03 (2H, t, OCH2CH2), 3.86 (3H, s, CH3O), 3.02 (2H, td, CONH-CH2), 2.22 (2H, m, CH2CONH), 1.94 (2H, m, OCH2CH2CH2CONH), 1.40-1.42 (5H, CH3CHNH + CONHCH2CH2(CH2)9CH3), 1.2-1.36 (14H, m, CH2(CH2)7CH3), 0.84 (3H, t, CH2(CH2)9CH3).

Fmoc-ONV-CH2 (CH2)6 CH3 (1, n=6), To a solution of Fmoc-ONV-COOH (300 mg, 0.57 mmol) and HBTU (262.8 mg, 0.69 mmol) in 3.5 mL of anhydrous DMF, EDIPA (149.1 mg, 1.15 mmol) was added dropwise. The solution was cooled on ice and added the solution of octylamine in 0.5 mL of EtOH that was also cooled on ice. After stirring for 30 min at 0 °C, the mixture was left overnight at room temperature. The resulting precipitate was filtered and washed with DMF (two times) followed by in vacuo drying. Product 1 (n=6) (average yield = 35.4%) was obtained as an amorphous white powder. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6), shown in Figure S3, δ ppm 8.07 (1H, -NH-Fmoc), 7.24-7.46, 7.63-7.65, and 7.86-7.89 (10H, Ar-H), 7.80 (1H,t, -NHCO), 5.20 (1H, m, -CH(CH3)NH), 4.27 (2H,CH2O), 4.17 (1H,CH2CH-Fmoc) 4.03 (2H, t, OCH2CH2), 3.86 (3H, s, CH3O), 3.02 (2H, td, CONH-CH2), 2.22 (2H, m, CH2CONH), 1.94 (2H, m, OCH2CH2CH2CONH), 1.40-1.42 (5H, CH3CHNH + CONHCH2CH2(CH2)9CH3), 1.2-1.36 (10H, m, CH2(CH2)5CH3), 0.84 (3H, t, CH2(CH2)9CH3).

NH2-ONV-CH2 (CH2)n CH3 (2)

Piperidine was added drop wise to a solution of 1 (0.6 mmol) in anhydrous DMF (3 mL) to reach a final concentration of 2M.47 The solution was stirred at room temperature for 2 h, and then DMF was removed by evaporation. The residue was dissolved in MeOH and the resulting precipitate was removed by filtration. After evaporating the filtrate solution was obtained quantitatively as a pale yellow solid. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) of 2 (n=10), shown in Figure S4, δ ppm 7.80 (1H,t, -NHCO), 7.24-7.46 (2H, Ar-H), 4.70 (1H, m, -CH(CH3)NH), 4.02 (2H, t, OCH2CH2), 3.91 (3H, s, CH3O), 3.03 (2H, td, CONH-CH2), 2.22 (2H, m, CH2CONH), 1.96 (2H, m, OCH2CH2CH2CONH), 1.41-1.43 (5H, CH3CHNH + CONHCH2CH2(CH2)9CH3), 1.2-1.27 (18H, m, CH2(CH2)9CH3), 0.84 (3H, t, CH2(CH2)9CH3). 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) of 2 (n=8), shown in Figure S5, δ ppm 7.81 (1H,t, -NHCO), 7.24-7.46 (2H, Ar-H), 4.70 (1H, m, -CH(CH3)NH), 4.02 (2H, t, OCH2CH2), 3.91 (3H, s, CH3O), 3.03 (2H, td, CONH-CH2), 2.22 (2H, m, CH2CONH), 1.96 (2H, m, OCH2CH2CH2CONH), 1.41-1.43 (5H, CH3CHNH + CONHCH2CH2(CH2)9CH3), 1.2-1.27 (14H, m, CH2(CH2)7CH3), 0.84 (3H, t, CH2(CH2)9CH3). 1H NMR (300 MHz, Methanol-d4) of 2 (n=6), shown in Figure S6, δ ppm 8.01 (1H,t, -NHCO), 7.24-7.46 (2H, Ar-H), 4.70 (1H, m, -CH(CH3)NH), 4.02 (2H, t, OCH2CH2), 3.91 (3H, s, CH3O), 3.03 (2H, td, CONH-CH2), 2.22 (2H, m, CH2CONH), 1.96 (2H, m, OCH2CH2CH2CONH), 1.41-1.43 (5H, CH3CHNH + CONHCH2CH2(CH2)9CH3), 1.2-1.27 (10H, m, CH2(CH2)5CH3), 0.84 (3H, t, CH2(CH2)9CH3).

Sulfonate-ONV-CH2 (CH2)n CH3 (3)

1.4-butane sultone (2.1 eq, 0.739 mmol) was added to a solution of 2 (1.0 eq, 0.352 mmol) with Et3N (2.0 eq) in acetonitrile (2 mL) and then the flask was sealed.48 The mixture was stirred and heated to ∼90 °C for 48 h. After removing the solvent by evaporation a light yellow viscous oil was obtained quantitatively. The oil was suspended in water and a NH4OH (aq) solution was added dropwise until pH ∼8 was reached. The surfactant solutions were centrifuged at 10 krpm for 30s and then the supernatant was collected for further study. ESI-MS calc'd. m/z for C29H50N3O8S-[M-H]- 600.79, found: 600.3; m/z for C27H46N3O8S-[M-H]- 572.73, found: 572.2; m/z for C25H42N3O8S-[M-H]- 544.68, found:544.2.

Measurement of electrical conductivity

A 3 wt % solution of each of the synthesized surfactants (ONV-C8, ONV-C10, and ONV-C12) was prepared. Small aliquots of each surfactant stock solutions were added to 2.5 mL of water under continuous stirring. The conductivity was then measured at room temperature after the addition of each aliquot to reach a final volume of 5 mL. As a control experiment, aliquots of 3 wt % sodium dodecyl sulfate solution were added into 2.5 mL of water and its conductivity was recorded the same way as it was done with the other surfactants.

TEM negative staining and characterization

The surfactant aqueous solutions were sonicated for 30 min and allowed to settle in a dark container (to prevent possible degradation) for 2 h. TEM samples were prepared by pipetting one drop of the surfactant aqueous solution onto a formva-coated copper TEM grid with carbon film. The samples were stained by 2 % aqueous phosphotungstic acid for negative staining. TEM was conducted on a Tecnai C12 Ultra Twin TEM instrument operated at 120 kV and images were collected using a Gatan CCD image system with digital micrograph software program.

Photolysis

The surfactants were irradiated using a Thermo Scientific™ Pierce™ UVP 3UV Ultraviolet Lamp (8W, 115V, 60Hz, Wavelength settings 365, 302 and 254 nm; 394 × 76 × 114mm L × W × D). A volume of ∼2 mL of the synthesized surfactant solutions were diluted to ∼0.02 % were irradiated in a 1 × 1 cm quartz cuvette using an irradiation wavelength of 365 nm. The surfactant UV-Vis spectra were first taken at time 0 to establish a baseline. Then, the photolytic degradation as a function of time was monitored by UV-Vis spectroscopy using a Cary 50 Scan UV-Vis spectrometer.

Results and Discussion

We synthesized a series of surfactants with different lengths of hydrophobic alkyl chain lengths (Scheme 1). The synthesis was carried out using an Fmoc-protected ONV photolabile linker that was coupled with octylamine (n=6, C8), decylamine (n=8, C10), and dodecylamine (n=10, C12), respectively, in the presence of HBTU and EDIPA to produce compounds (1). The Fmoc group was deprotected by using piperidine in anhydrous DMF. The resulting compounds were characterized by 1H-NMR (Figure S1-6). The surfactant precursors with different alkyl chain lengths of 8, 10, 12 carbons were prepared by reacting the deprotected products with 1,4-butane sultone in acetonitrile with Et3N at ∼90 °C for 48 hrs. A family of water-soluble surfactants (3) was obtained through deprotonation with NH4OH in water. The surfactant solutions were centrifuged and then the supernatant was collected for further analysis. The identity of water-soluble surfactant molecule (3) was confirmed by electrospray ionization (ESI)- MS.

The self-assembly of amphiphilic surfactants into soft-matter structures such as micelles, vesicles, or emulsions is a key characteristics of surfactant molecules. We first used conductometry to determine the critical micelle concentration (CMC). The addition of surfactant molecules into an aqueous solution causes an increase in the number of charge carriers and as a result an increase in conductivity. Above CMC, the addition of surfactant only increases the concentration of micelles leaving the monomer concentration relatively unchanged. Because micelles are larger, they are less efficient charge carriers and therefore, the rate at which conductivity increases against surfactant concentration decreases. After preparing solutions of the synthesized surfactants (ONV-C12, ONV-C10, and ONV-C8), we measured the conductivity by adding an aliquot of each of the surfactant solutions into deionized water. From the measured conductivity, the molar conductivity was obtained and plotted against the square root of the concentration ( )35 of each surfactant solution (ONV-C12 and ONV-C10 and ONV-C8) in Figure 2. The breaking point of the surfactant solution was localized by the intersection of two linear functions with different slopes. From such breaking point, we can estimate the critical concentration for the formation of supramolecular structures by these surfactants. The breaking point obtained for ONV-C10 was at ∼0.107 (Figure 2A), which indicates the structures began to form at ∼11 mM. The breaking point obtained for ONV-C12 was at ∼0.086 (Figure 2B), which indicates the structures begin to form at ∼7 mM. After reaching the specific concentration, the molar conductivity decreased against the of the surfactant solutions suggesting that the number of self-assembled supramolecular structures produced by surfactant monomers also decreased. In the case of ONV-C8 (Figure 2C), we did not observe a breaking point on the curve implying that the ONV-C8 surfactant molecules are more stable as monomers than as supramolecular structures as it is to be expected for an alkyl chain of less than 10 carbons.49

Figure 2.

The molar conductivity of A) ONV-C10, B) ONV-C12 and C) ONV-C8, as a function of the square root of concentration of the synthesized surfactant solutions.

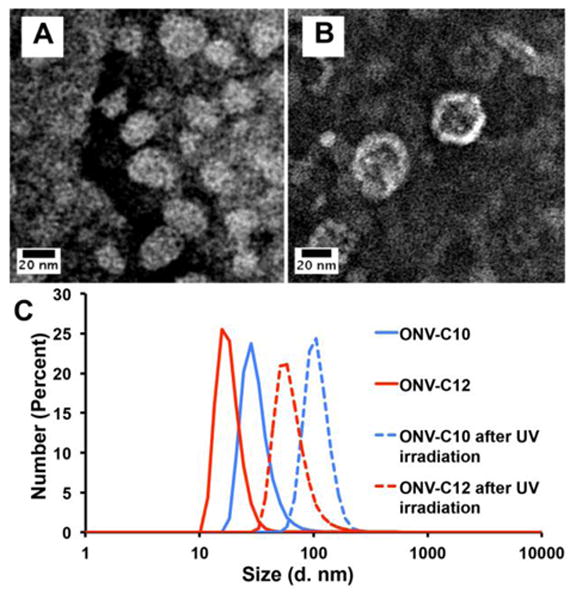

The supramolecular structures formed by ONV-C10 and ONV-C12 were further investigated using negatively stained TEM. The TEM images indicated the formation of two different types of self-assembled spherical structures by ONV-C12 and ONV-C10 surfactant solutions. ONV-C12 surfactant formed irregular shaped spherical structures, ranging in size from 12 to 24 nm (Figure 3A and Figure S7) suggesting micelle structures.50 For the ONV-C10 surfactant molecules, we observed large spherical structures with a size distribution of ∼12 to ∼40 nm (Figure 3B and Figure S8) that suggest vesicular structures.51 The particle-size distribution before UV irradiation was further studied using DLS (solid lines in Figure 3C). The average hydrodynamic diameter of aggregates formed by ONV-C12 (∼17-18 nm) and ONV-C10 (∼32-34 nm) was in agreement with the TEM observations. From these results we can conclude that we have generated two different supramolecular structures. For ONV-C8, we were unable to observe the formation of any supramolecular structures, which is to be expected for a hydrophobic tail of that length.

Figure 3.

TEM images with negative staining by 2 % phosphotungstic acid of (A) ONV-C12 and (B) ONV-C10 surfactant solutions, and (C) particle-size distribution before (solid lines) and after UV irradiation (dashed lines) obtained by DLS.

We further demonstrated the photo-degradation of the synthesized surfactant molecules and the supramolecular structures assembled from them under 365 nm irradiation that is within the molecules' absorption band. The use of veratryl-based nitrobenzene ring with an additional alkoxy group can facilitate the photolytic cleavage with > 350 nm UV light comparable to o-nitrobenzyl linkers.39, 44 The surfactant solutions were exposed in a 1 × 1 cm quartz cuvette to a 365 nm UV lamp in 120-second intervals. A UV-Vis spectrum was taken after each of the illumination periods. Figure 4A depicts a change in the UV-Vis spectra over time for the ONV-C10 surfactant solution. We observed a decrease in the absorption band at ∼350 nm and an increase in the absorption band at ∼280 nm. The increase in the absorption wavelength at 280 nm suggests the formation of smaller molecules as a result of the photo-degradation of the surfactant. A similar trend was observed for surfactant ONV-C12 (Figure 4B). In the case of surfactant ONV-C8, we observed a different trend where the band at ∼350 nm blue shifted over time and the band at ∼280 nm increased over time (Figure 4C and Figure S9). This suggests that the photo-degradation of ONV-C8 happens through a slower and/or different pathway. The particle-size distribution after UV irradiation was also studied using DLS (dash lines in Figure 3C). The average hydrodynamic diameter after UV irradiation of ONV-C10 (Figure S10) and ONV-C12 (Figure S11) was ∼100 nm. This is consistent with the formation of agglomerates that is observed after surfactant degradation.52 An even more direct visualization of the degradation process is shown in Figure 5. When exposed to 365 nm UV light for 60 min, the solutions were observed to undergo a marked color change except for ONV-C8, in which the turbidity increased rather than a color change.

Figure 4.

The change of absorbance against wavelength at different irradiation times for (A) ONV-C10, (B) ONV-C12 and (C) ONV-C8.

Figure 5.

Photos showing the color change of each surfactant solution before and after photoirradiation.

We also carried out high-resolution Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance (FT-ICR) MS analysis of ONV-C10 before and after UV irradiation (Figure 6). Before photoirradiation, under the negative ion mode MS the m/z peak for C27H46N3O8S- at 572.3 was observed. After photoirradiation at 365 nm for 60 min, the positive ion mode MS data showed the main fragmentation product for the decomposed C23H36N2O5 (see Figure 1) as [M+H]+, [M+Na]+, and [M+NH4]+. Positive ion mode was used for the MS analysis of the photoirradiated surfactants molecules due to the difficulty in obtaining the molecular ion of the major photodegradation products in the negative ion mode. The same experiment conducted for ONV-C12 and ONV-C8 also showed the expected fragmentation products as seen in Figure S12 and Figure S13.

Figure 6.

(A) Negative ion FT-ICR MS analysis before UV-irradiation and, (B) positive ion FT-ICR MS analysis after UV-irradiation of ONV-C10.

Conclusions

We have shown the synthesis and characterization of a novel series of surfactants that contain a photolabile ONV-based linker between a hydrophilic head and a hydrophobic tail with different lengths of alkyl chains. Using UV-Vis, MS, and DLS, we demonstrated the successful degradation of the surfactants and the assembled supramolecular structures upon 365 nm UV light irradiation. Furthermore, varying the length of the alkyl chain leads to different self-assembly behaviors. Additionally, these surfactants could be further developed for biological applications taking advantage of the non-zero two-photon cross section of nitroveratryl moieties.53 These surfactants are also potentially useful as removable templates for the synthesis of meso- or microporous materials4 or as removable surface-acting agents for extracting hydrophobic proteins.11 These represent a new type of highly versatile photolabile surfactants that could have a wide range of potential applications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the support of NIH R01GM117058 for this research (to S.J. and Y.G.) and an NIH Fellowship (F32HL128006) to Tania M. Guardado-Alvarez.

Footnotes

Supporting Information: The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

MS data for ONV-C12 and ONV-C8, NMR data for surfactant synthesis, Expanded UV-Vis spectra of ONV-C8, TEM images and DLS data after UV irradiation of ONV-C10 and ONV-C12.

References

- 1.Tolbert SH, Firouzi A, Stucky GD, Chmelka BF. Magnetic field alignment of ordered silicate-surfactant composites and mesoporous silica. Science. 1997;278:264–268. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kresge CT, Leonowicz ME, Roth WJ, Vartuli JC, Beck JS. Ordered mesoporous molecular sieves synthesized by a liquid-crystal template mechanism. Nature. 1992;359:710–712. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guardado-Alvarez TM, Sudha Devi L, Russell MM, Schwartz BJ, Zink JI. Activation of Snap-Top Capped Mesoporous Silica Nanocontainers Using Two Near-Infrared Photons. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:14000–14003. doi: 10.1021/ja407331n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wan Y, Zhao D. On the controllable soft-templating approach to mesoporous silicates. Chem Rev. 2007;107:2821–2860. doi: 10.1021/cr068020s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Che S, Garcia-Bennett AE, Yokoi T, Sakamoto K, Kunieda H, Terasaki O, Tatsumi T. A novel anionic surfactant templating route for synthesizing mesoporous silica with unique structure. Nat Mater. 2003;2:801–805. doi: 10.1038/nmat1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eriksson S, Nylén U, Rojas S, Boutonnet M. Preparation of catalysts from microemulsions and their applications in heterogeneous catalysis. Appl Catal A. 2004;265:207–219. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holmberg K. Organic reactions in microemulsions. Curr Opin Colloid Interface Sci. 2003;8:187–196. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rusling JF. Controlling electrochemical catalysis with surfactant microstructures. Acc Chem Res. 1991;24:75–81. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mittal KL. Solution Chemistry of Surfactants. Vol. 1 Springer Science & Business Media 2012; [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nardello-Rataj V, Caron L, Borde C, Aubry JM. Oxidation in three-liquid-phase microemulsion systems using “Balanced Catalytic Surfactants”. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:14914–14915. doi: 10.1021/ja805220p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang YH, Gregorich ZR, Chen AJ, Hwang L, Guner H, Yu D, Zhang J, Ge Y. New Mass-Spectrometry-Compatible Degradable Surfactant for Tissue Proteomics. J Proteome Res. 2015;14:1587–1599. doi: 10.1021/pr5012679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saveliev SV, Woodroofe CC, Sabat G, Adams CM, Klaubert D, Wood K, Urh M. Mass spectrometry compatible surfactant for optimized in-gel protein digestion. Anal Chem. 2013;85:907–914. doi: 10.1021/ac302423t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Newby ZE, D O'Connell J, Gruswitz F, Hays FA, Harries WE, Harwood IM, Ho JD, Lee JK, Savage DF, Miercke LJ. A general protocol for the crystallization of membrane proteins for X-ray structural investigation. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:619–637. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malmsten M. Soft drug delivery systems. Soft Matter. 2006;2:760–769. doi: 10.1039/b608348j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soussan E, Cassel S, Blanzat M, Rico-Lattes I. Drug delivery by soft matter: matrix and vesicular carriers. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:274–288. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Torchilin VP. Structure and design of polymeric surfactant-based drug delivery systems. J Controlled Release. 2001;73:137–172. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00299-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Der Woude I, Wagenaar A, Meekel AAP, Ter Beest MBA, Ruiters MHJ, Engberts JBFN, Hoekstra D. Novel pyridinium surfactants for efficient, nontoxic in vitro gene delivery. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1997;94:1160–1165. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirby AJ, Camilleri P, Engberts JBFN, Feiters MC, Nolte RJM, Söderman O, Bergsma M, Bell PC, Fielden ML, García Rodríguez CL. Gemini surfactants: new synthetic vectors for gene transfection. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2003;42:1448–1457. doi: 10.1002/anie.200201597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rapoport N. Physical stimuli-responsive polymeric micelles for anti-cancer drug delivery. Prog Polym Sci. 2007;32:962–990. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song S, Song A, Hao J. Self-assembled structures of amphiphiles regulated via implanting external stimuli. RSC Adv. 2014;4:41864–41875. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feng Y, Chu Z, Dreiss CA. Smart Wormlike Micelles: Design, Characteristics and Applications. Springer; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chu Z, Dreiss CA, Feng Y. Smart wormlike micelles. Chem Soc Rev. 2013;42:7174–7203. doi: 10.1039/c3cs35490c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown P, Butts CP, Eastoe J. Stimuli-responsive surfactants. Soft Matter. 2013;9:2365–2374. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao N, Qi L. Low-Temperature Synthesis of Star-Shaped PbS Nanocrystals in Aqueous Solutions of Mixed Cationic/Anionic Surfactants. Adv Mater. 2006;18:359–362. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guardado-Alvarez TM, Devi LS, Vabre JM, Pecorelli TA, Schwartz BJ, Durand JO, Mongin O, Blanchard-Desce M, Zink JI. Photo-redox activated drug delivery systems operating under two photon excitation in the near-IR. Nanoscale. 2014;6:4652–4658. doi: 10.1039/c3nr06155h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin Y, Han X, Huang J, Fu H, Yu C. A facile route to design pH-responsive viscoelastic wormlike micelles: smart use of hydrotropes. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2009;330:449–455. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2008.10.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chu Z, Feng Y. pH-switchable wormlike micelles. Chem Commun. 2010;46:9028–9030. doi: 10.1039/c0cc02415e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dan K, Pan R, Ghosh S. Aggregation and pH Responsive Disassembly of a New Acid-Labile Surfactant Synthesized by Thiol− Acrylate Michael Addition Reaction. Langmuir. 2010;27:612–617. doi: 10.1021/la104445h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klaikherd A, Nagamani C, Thayumanavan S. Multi-stimuli sensitive amphiphilic block copolymer assemblies. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:4830–4838. doi: 10.1021/ja809475a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fameau AL, Arnould A, Lehmann M, von Klitzing R. Photoresponsive self-assemblies based on fatty acids. Chem Commun. 2015;51:2907–2910. doi: 10.1039/c4cc09842k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kang HC, Lee BM, Yoon J, Yoon M. Synthesis and surface-active properties of new photosensitive surfactants containing the azobenzene group. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2000;231:255–264. doi: 10.1006/jcis.2000.7158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McElhanon JR, Zifer T, Kline SR, Wheeler DR, Loy DA, Jamison GM, Long TM, Rahimian K, Simmons BA. Thermally cleavable surfactants based on furan-maleimide Diels-Alder adducts. Langmuir. 2005;21:3259–3266. doi: 10.1021/la047074z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tong R, Hemmati HD, Langer R, Kohane DS. Photoswitchable nanoparticles for triggered tissue penetration and drug delivery. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:8848–8855. doi: 10.1021/ja211888a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nuyken O, Meindl K, Wokaun A, Mezger T. Photolabile surfactants based on the diazosulphonate group 2. 4-(Acyloxy) benzenediazosulphonates and 4-(acylamino) benzenediazosulphonates. J Photochem Photobiol A: Chem. 1995;85:291–298. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mezger T, Nuyken O, Meindl K, Wokaun A. Light decomposable emulsifiers: application of alkyl-substituted aromatic azosulfonates in emulsion polymerization. Prog Org Coat. 1996;29:147–157. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shin JY, Abbott NL. Using light to control dynamic surface tensions of aqueous solutions of water soluble surfactants. Langmuir. 1999;15:4404–4410. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang Y, Ma N, Wang Z, Zhang X. Photocontrolled Reversible Supramolecular Assemblies of an Azobenzene-Containing Surfactant with α-Cyclodextrin. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:2823–2826. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sakai H, Ebana H, Sakai K, Tsuchiya K, Ohkubo T, Abe M. Photo-isomerization of spiropyran-modified cationic surfactants. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2007;316:1027–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2007.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holmes CP. Model studies for new o-nitrobenzyl photolabile linkers: Substituent effects on the rates of photochemical cleavage. J Org Chem. 1997;62:2370–2380. doi: 10.1021/jo961602x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holmes CP, Jones DG. Reagents for combinatorial organic synthesis: development of a new o-nitrobenzyl photolabile linker for solid phase synthesis. J Org Chem. 1995;60:2318–2319. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Farcy N, De Muynck H, Madder A, Hosten N, De Clercq PJ. A pentaerythritol-based molecular scaffold for solid-phase combinatorial chemistry. Org Lett. 2001;3:4299–4301. doi: 10.1021/ol016980p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rinnová M, Novakova M, Kasicka V, Jiracek J. Side Reactions during Photochemical Cleavage of an a-Methyl-6-nitroveratryl-based Photolabile Linker. J Pept Sci. 2000;6:355–365. doi: 10.1002/1099-1387(200008)6:8<355::AID-PSC261>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pasparakis G, Manouras T, Argitis P, Vamvakaki M. Photodegradable polymers for biotechnological applications. Macromol Rapid Commun. 2012;33:183–198. doi: 10.1002/marc.201100637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhao H, Sterner ES, Coughlin EB, Theato P. O-nitrobenzyl alcohol derivatives: Opportunities in polymer and materials science. Macromolecules. 2012;45:1723–1736. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guillier F, Orain D, Bradley M. Linkers and cleavage strategies in solid-phase organic synthesis and combinatorial chemistry. Chem Rev. 2000;100:2091–2158. doi: 10.1021/cr980040+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hwang L, Ayaz-Guner S, Gregorich ZR, Cai W, Valeja SG, Jin S, Ge Y. Specific enrichment of phosphoproteins using functionalized multivalent nanoparticles. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:2432–2435. doi: 10.1021/ja511833y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou G, Khan F, Dai Q, Sylvester JE, Kron SJ. Photocleavable peptide-oligonucleotide conjugates for protein kinase assays by MALDI-TOF MS. Molecular BioSystems. 2012;8:2395–2404. doi: 10.1039/c2mb25163a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang SS. Dyes and methods of marking biological material US 8710244 B2. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mandavi R. PhD Thesis. Pt. Ravishankar Shukla University; India: 2011. Kinetic studies of some Esters and Amides in presence of micelles. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huang H, Kowalewski T, Remsen EE, Gertzmann R, Wooley KL. Hydrogel-Coated Glassy Nanospheres: A Novel Method for the Synthesis of Shell Cross-Linked Knedels. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:11653–11659. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kabanov AV, Bronich T, Kabanov V, Yu K, Eisenberg A. Spontaneous Formation of Vesicles from Complexes of Block Ionomers and Surfactants. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:9941–9942. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jiang Y, Wang Y, Ma N, Smet M, Zhang X. Reversible Self-Organization of a UV-Responsive PEG-Terminated Malachite Green Derivative: Vesicle Formation and Photoinduced Disassembly. Langmuir. 2007;23:4029–4034. doi: 10.1021/la063305l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kantevari S, Hoang CJ, Ogrodnik J, Egger M, Niggli E, Ellis-Davies GC. Synthesis and Two-photon Photolysis of 6-(ortho-Nitroveratryl)-Caged IP3 in Living Cells. ChemBioChem. 2006;7:174–180. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200500345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.