Abstract

Purpose of the review

This review highlights novel insights into the role of GABAA receptors in mediating clinically relevant actions of anesthetic agents.

Recent findings

GABAA receptors in the hippocampus are located on glutamatergic pyramidal cells and GABAergic interneurons. Etomidate-induced inhibition of a synaptic correlate of learning and memory is caused by receptors on non-pyramidal neurons, likely on interneurons that incorporate α5-subunits. Selective enhancement of α2-subunit containing GABAA receptors in the spinal cord provides antihyperalgesia against inflammatory and neuropathic pain without causing sedation, motor impairment and tolerance development. Inflammation, traumatic brain injury and exposure to anesthetic agents modify the expression patterns of GABAA receptors in a subtype-specific manner. These modifications may persist for weeks. The neuroactive steroid alphaxalone causes fast-onset and short duration anesthesia in humans. Cardiovascular and respiratory side effects are less severe than with propofol.

Summary

Identification of the molecular and cellular substrates involved in anesthesia and insights into disease- and drug-induced alterations in the expression patterns of GABAA receptors in the central nervous system are emphasizing the need for individualized anesthesia care. Introducing neuroactive steroids into clinical anesthesia is expected to reduce cardiovascular and respiratory side effects.

Keywords: α2- GABAA receptors, α5- GABAA receptors, amnesia, antihyperalgesia, inflammation, brain injury

Introduction

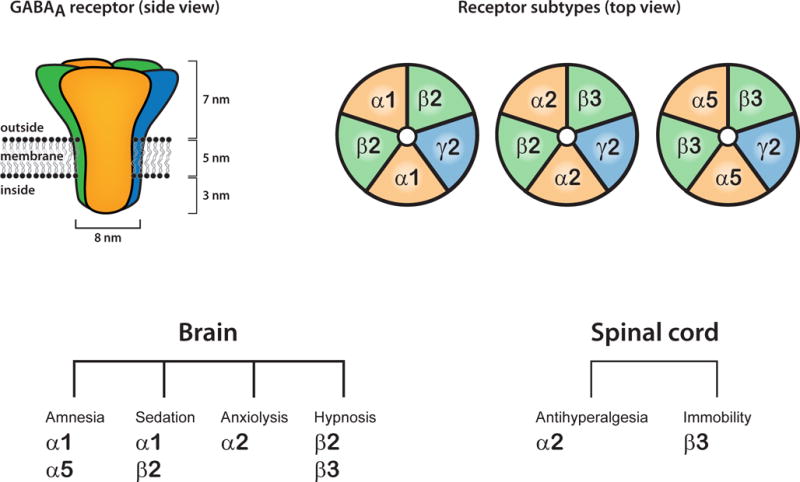

GABAA receptors are ligand-gated chloride channels composed of five protein subunits.[1] Their endogenous agonist γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is the major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system (CNS). GABAA receptors are targeted by most anesthetic agents in current clinical use.[2] Acting as positive allosteric modulators they enhance the function of GABAA receptors, thereby decreasing the activity and excitability of central neurons. Nineteen different protein subunits of the GABAA receptor have been identified, giving rise to many receptor subtypes fulfilling different physiological functions (Figure 1).[3] These subtypes are not uniformly distributed throughout the CNS. Even within the same brain region their expression varies between cell types and even subcellular regions.[4] It is generally accepted that at clinically relevant concentrations anesthetic agents such as propofol, etomidate and isoflurane, interact with several distinct GABAA receptor subtypes.[5] The specific contributions of GABAA receptor subtypes to the pharmacological properties of general anesthetic drugs are currently under investigation. Here we will highlight novel findings of how anesthetics interfere with learning and memory and how they affect spinal pain processing. We will review recent evidence that anesthetic agents, inflammation and brain injury can cause rapid and long-lasting changes in the surface expression of GABAA receptors, which in turn alter the patient’s sensitivity to anesthetic drugs. Because GABAA receptors play a pivotal role in regulating neuronal excitability, it is not surprising that their activity is modulated by endogenous molecules. For example, endogenous steroids are known to act as powerful positive allosteric modulators at GABAA receptors.[6] We will also discuss efforts to re-introduce alphaxalone into clinical anesthesia and elucidate the potential benefits of neuroactive steroids.

Figure 1. GABAA receptors and anesthetic actions.

GABAA receptors assemble from five protein subunits.[47] Most GABAA receptors are composed of two α-, two β- and a γ-subunit. However, nineteen different protein subunits are expressed in central neurons, giving rise to many potentially existing receptor subtypes. Some of these are indicated on the upper right. There is evidence that receptor subtypes harboring α1- and β2 subunits mediate the sedative actions of benzodiazepines, etomidate and propofol.[48,49] Furthermore, GABAA receptors incorporating α2-subunits mediate the anxiolytic and antihyperalgesic actions of benzodiazepines.[18,50] α5-containing GABAA receptors are densely expressed in the hippocampus and mediate the amnestic effect of anesthetics.[9] The amnestic, sedative, anxiolytic and hypnotic properties of anesthetic agents are mediated by GABAA receptors in the brain whereas antihyperalgesia and immobility is caused by spinal receptors.[2]

Impairment of learning and memory by anesthetic agents

The hippocampal formation takes a central role in learning and memory. Anesthetic actions within the hippocampus itself are thought to cause anesthetic-induced amnesia.[7] This idea is supported by the observation that at small amnestic concentrations anesthetic agents depress hippocampal long term potentiation (LTP), a major cellular mechanism that underlies learning and memory.[8,9] It has been discovered previously by studying α5-global knockout mice that etomidate impairs synaptic plasticity and memory via modulation of α5-subunit containing GABAA receptors. [9] which are expressed primarily in the hippocampus[10,11] and that this impairment can be reversed by the negative allosteric α5-selective modulator, L-655,708.[12] However, the neuronal population at which etomidate effects these changes is still unknown. It was generally assumed that pyramidal neurons, e.g. in CA1, but also other hippocampal regions, would be such cellular targets, as these neurons have been shown to play a role in learning and memory, and α5-GABAA receptors on these neurons would inhibit these neurons via producing an inhibitory tonic current. However, in conditional knockout mice in which the α5-subunit is lacking selectively in CA1 pyramidal neurons, etomidate surprisingly suppressed long-term potentiation in CA1 pyramidal neurons.[13] The level of tonic current was similar to levels in floxed control mice and α5 global knockout mice. In the CA1-specific α5 knockout mice, in the presence of etomidate there was a non-significant trend to an increase in tonic current, to levels not different from those in the global α5-knockout mice. This indicates that etomidate’s effect on tonic inhibition in CA1 pyramidal neurons is not the mechanism by which etomidate inhibits learning and memory. Furthermore these findings suggest that α5-GABAA receptors on non-pyramidal cells, potentially interneurons, may be the targets for the amnestic action of etomidate.

To determine whether modulation of β3-containing GABAA receptors by etomidate impairs learning and memory, etomidate was tested in β3(N265M) mice in which the β3-subunits have been rendered insensitive to modulation by etomidate.[14] In hippocampal slices of these mice, etomidate did not enhance tonic inhibition, but it still blocked long-term potentiation in CA1 pyramidal cells, and it impaired fear conditioning to context.[15] These results suggest a dissociation between tonic inhibition and impairment of memory: while β3-GABAA receptors mediate enhancement of tonic inhibition, they do not mediate impairment of memory elicited by this drug. In conjunction with the observation that amnestic concentrations of etomidate enhance receptor activity at recombinant α5β2γ2- and α5β3γ2-, but not α5β1γ2-GABAA receptors,[15] the findings mean that etomidate most likely impairs memory via receptors containing the β2-subunit, although they do not rule out the possibility that etomidate may inhibit CA1 pyramidal neurons by mechanism different from tonic inhibition, e.g., slow phasic inhibition. Performing similar experiments with β2(N265M)-mice would unequivocally confirm the role of β2-GABAA receptors in LTP suppression and fear conditioning to context.

Actions of benzodiazepines in the spinal cord

Systemically applied classical benzodiazepines do not have an analgesic action. However, it is known that in rodents intrathecally applied and thus primarily spinally acting benzodiazepines have an antihyperalgesic action in a variety of pain models, including models of inflammatory and of neuropathic pain.[16] This antihyperalgesic action does not involve supraspinal sites.[17] In a recent study, antihyperalgesic effects and potential side effects (such as sedation, muscle relaxation and motor impairment) of positive allosteric modulation of single GABAA receptor subtypes as defined by their α-subunits was examined in a panel of mice in which three out of the four diazepam-sensitive α-subunits α1, α2, α3, and α5 were rendered diazepam-insensitive by histidine to arginine knock-in point mutations.[18] Modulation of α2-containing GABAA receptors elicited approximately 60% of the maximally possible anti-hyperalgesic effect (with other contributions provided by α3-GABAA receptors and α5-GABAA receptors). While positive modulation of α1-GABAA receptors elicits sedation, positive modulation of α2-GABAA receptors and of α3-GABAA receptors elicits muscle relaxation, while modulation of α3-GABAA receptors but not of α2-GABAA receptors impairs motor coordination.

In mice in which α2/α3/α5-GABAA receptors are sensitive to diazepam, with an acute dose of diazepam, maximum possible anti-hyperalgesia is achieved, but after 10 days of chronic adminstration of diazepam, this effect is completely abolished, indicating development of tolerance. However, in mice in which only α2-GABAA receptors are modulated by diazepam, both acute and a 10 day chronic administration of diazepam result in approximately 60% of the maximal anti-hyperalgesic action. Thus, there is no development of tolerance. Development of tolerance may be circuit-specifc as these mice develop tolerance to the locomotor increasing effect of diazepam in these mice. It is currently not known whether in these mice tolerance develops to the muscle relaxant action of diazepam. Overall, α2-specific modulation would likely have strong antihyperalgesic actions but relatively limited unwanted side effects. It could further be demonstrated that in animals in which diazepam or midazolam only modulate α2-GABAA receptors the antihyperalgesic action of diazepam or midazolam occur at doses that already elicit sedative actions in mice in which these compounds only modulate α1-GABAA receptors.

Drugs acting only at a single subtype of benzodiazepine-sensitive GABAA receptors remain to be introduced into clinical practice in the future. However, the study of Ralvenius and coworkers suggests variable potency and efficacy of different benzodiazepines in modulating α1-GABAAreceptors.[18] Thus, at slightly sedating concentrations some benzodiazepines approved for human use may display anti-hyperalgesic actions. When clonazepam and clobazam were tested at mildly sedating equiconvulsive dose in cutaneous UVB irradiation-induced secondary hyperalgesia in humans, these compounds accelerated recovery from hyperalgesia by 28.6% (CI 4.5–52.6] and 15.7% [CI 0.8–30.5], respectively.[19] These results provide the first proof-of-principle evidence supporting an antihyperalgesic action of GABAA receptor modulation in humans.

Anesthetic agents alter surface expression of GABAA receptors

We have mentioned previously that α5-GABAA receptors mediate the amnesic action of etomidate.[9] A new study found that etomidate exerts cellular changes and pharmacological actions long after administration of the drug.[20] A single dose of etomidate (8 mg/kg) impairs memory performance in the novel object recognition task both 24 hours and 72 hours, but not 1 week after drug administration. Likewise, field postsynaptic potential slope was decreased by etomidate at the 24 hour time point, but not at the 1 week timepoint. In hippocampal slices, the α5-GABAA receptor mediated current density was increased in CA1 pyramidal neurons 24 hours, 72 hours, and 1 week after administration of etomidate, but not 2 weeks after administration of etomidate. This indicates that α5-GABAA receptor function is altered long after etomidate is presumably eliminated from the organism. The surface expression of α5-GABAA receptors but not total expression of α5-GABAA receptors was increased 24 hours and 1 week, but not 2 weeks after administration of etomidate, suggesting an intracellular redistribution of these receptors. The nature of these sustained changes is currently unknown. It is noteworthy that in neuronal cultures treated with etomidate-incubated astrocytes tonic current density is increased, compared to vehicle-treated astrocytes.[20] This may suggest that GABAA receptors on astrocytes may contribute to enhancement of tonic current in CA1 pyramidal neurons. Negative allosteric modulation of α5-GABAA receptors reversed the memory deficits. Furthermore, the authors tested the effects of the volatile anesthetic isoflurane on cell-surface expression of α5-GABAA receptors. At a low, sedative dose isoflurane (0.7%, 20 minutes) was ineffective. However, at a higher, anesthetizing dose (1.3%, 60 minutes) isoflurane significantly increased cell-surface expression of α5-subunits, leaving the expression of δ-subunits unchanged. [20]

In another study the effect of propofol on the cell-surface expression of β3-GABAA receptor subunits were explored in cultured cortical neurons and in mice.[21] Propofol (10 μM, up to 60 min) facilitated membrane accumulation of β3-subunits and, unlike etomidate, increased the amplitudes of miniature IPSCs. These findings indicate that propofol potentiates synaptic inhibition via increasing the density of postsynaptic GABAA receptors. Furthermore, propofol blocked the interaction between β3-subunits and the β-adaptin subunit of adaptor protein 2, thereby reducing endocytosis of GABAA receptors.[21] Similar to propofol, diazepam can rapidly strengthen GABAA receptor-mediated synaptic transmission via increasing the number of postsynaptic receptors.[22] Interestingly, this effect required sustained neuronal activity and was not apparent under resting conditions. However, it is important to note that the duration of drug exposure seems to have a major impact on the changes induced in GABAA receptor trafficking. When cultured hippocampal neurons were treated with flurazepam for 24 hours (in the aforementioned studies propofol and diazepam were applied for up to one hour only), a dramatic decrease in surface and total levels of α2-subunit containing GABAA receptors occurred, whereas levels of α1-subunits remained unaltered.[23]

In summary, agents acting as positive allosteric modulators at GABAA receptors alter the gating kinetics and in addition can rapidly alter receptor trafficking. Although the underlying molecular mechanisms remain to be studied, there is evidence that these effects are specific for different GABAA receptor subtypes and strongly depend on the duration of drug exposure. Furthermore, different anesthetic agents seem to modify the surface expression of GABAA receptors in different ways.

Expression of GABAA receptors is modified by inflammation and brain injury

Systemic inflammation can cause cerebral dysfunction.[24–26] It has been proposed that elevated levels of the proinflammatory cytokine interleukin-1β compromise memory and learning by increasing the surface expression of α5-GABAA receptors in hippocampal pyramidal cells.[27] This raises the question whether inflammation modifies neuronal sensitivity to general anesthetic agents by altering the expression patterns of GABAA receptors in the brain. Pretreatment with the bacterial endotoxin lipopolysaccharide enhanced the hypnotic effects of etomidate and isoflurane in mice.[28] Furthermore, lippopolysaccharide and etomidate impaired contextual fear memory. In cultured hippocampal und cortical neurons interleukin-1β enhanced agonist-induced currents across GABAA receptors and promoted the actions of etomidate at the same receptors.[28] Collectively these findings suggest that systemic inflammation increases the surface expression of GABAA receptors thereby inducing neuronal sensitivity to general anesthetics.

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is recognized as a major health problem.[29] After initial brain damage secondary pathologies develop over the following days. Anesthetic agents acting via GABAA receptors are frequently used in these patients’ anesthesia to induce and maintain general anesthesia.[30] Drexel and coworkers assessed the expression of GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs in rats 6 hours and 4 months post-TBI in the hippocampus and thalamus.[31] In the hippocampus the expression of α1-, α2-, α5-, β2-, β3- γ2- and δ- GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs were down-regulated 6 and 24 hours post-TBI. However, these changes were transient and disappeared after 4 months. In the thalamus α1-, α4-, α2-, β2-, γ2- and δ- GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs were downregulated by TBI but recovery was largely absent for some of these subunits. How these dramatic changes relate to the surface expression of GABAA receptors and how the patient’s sensitivity to general anesthetic agents after TBI is altered remains to be investigated.

Neurosteroid analogues for providing anesthesia

Althesin® is a short acting intravenous anesthetic agent that was used in clinical anesthetic practice from 1972 to 1984. It is a mixture of the neuroactive steroids alphaxalone and alphadolone solved in water with the aid of the formulation vehicle Cremophor EL® and was withdrawn from the market because of hypersensitivity reactions caused by the excipient.[32] Synthetic neurosteroids like alphaxalone are analogues of naturally occurring neurosteroids.[33] Therefore these agents are expected to have fewer cardiovascular and respiratory side effects and the development of tolerance is reduced. Stress and brain injury both enhance endogenous neurosteroid de novo synthesis, which is probably part of a self-protecting reaction chain.[34] Moreover, a large body of evidence has accumulated that neurosteroids provide neuroprotection.[35] When administered together, neurosteroids and anesthetic agents can enhance GABAA receptor-mediated inhibition in a synergistic manner.[36] This finding suggests that the combined use of anesthetics and neurosteroids may significantly reduce dose requirements needed for clinical anesthesia, which in turn should reduce cardiovascular and respiratory side effects.

As mentioned before, the use of Althesin® in clinical anesthesia was discontinued due to the hypersensitivity reactions caused by Cremophor EL®. Therefore Goodchild and coworkers replaced Cremophor EL® with 7-sulfobutyl-ether-β-cyclodextrin (betadex), which has been successfully used to dissolve hydrophobic drugs in water for intravenous injections in humans.[37] Alphaxalone induced fast-onset anesthesia in rats at the same dose for both formulations. Remarkably, the dose that caused death in 50% of animals (LD50) was more than twofold higher with betadex as the formulation vehicle. A phase 1c trial compared the efficacy and safety of Phaxan™, an aqueous solution of alphaxalone and betadex with propofol.[38] Similar to propofol, Phaxan™ caused fast-onset and short duration anesthesia. However, respiratory depression and the decrease in systolic and diastolic blood pressure were less pronounced. Furthermore subjects did not complain of pain on injection with Phaxan™.

Conclusions

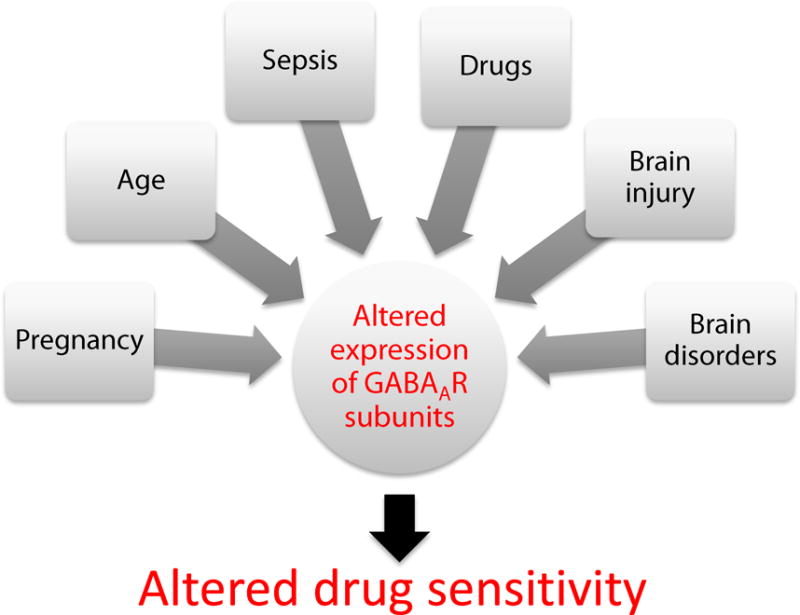

The sedative, amnestic, anxiolytic, hypnotic, muscle relaxant and antihyperalgesic actions of anesthetic agents involve distinct sub-populations of GABAA receptors. This observation is raising the question if there are ways to achieve some of these actions but not others by making use of subtype-selective drugs. Proof of principle studies have shown that amnesia can be achieved or prevented by selective modulation of receptors containing α5-subunits.[9,12,39] Furthermore, drugs that enhance the function of α2- but not α1-subunits should be useful for providing antihyperalgesia against inflammatory and neuropathic pain.[18] It is also important to consider that the expression pattern of GABAA receptor subtypes in the brain and spinal cord is altered by therapeutically relevant factors including drug usage[40], inflammation[41], injury[31], disease[42,43], age[44,45] and pregnancy (Figure 2)[46]. These novel findings are strengthening the need for individualized anesthesia care. Finally the use of neuroactive steroids is expected to reduce cardiovascular and respiratory side effects of anesthetic agents in current use.

Figure 2.

Factors affecting the expression pattern of GABAA receptor subunits, potentially altering the patient’s sensitivity to anesthetic drugs.

Summary points.

Selective enhancement of α2-GABAA receptor function causes antihyperalgesia without sedation.

The brain expression pattern of GABAA receptor subunits is substantially altered by the administration of anesthetic drugs, inflammation and brain injury, which in turn modifies the patient’s sensitivity to anesthetic agents.

Cardiovasuclar and respiratory side effects in human subjects are less severe if anesthesia is induced with alphaxalone than with propofol.

Acknowledgments

UR is supported by grants from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R01GM086448) and the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH095905) from the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institue of General Medical Sciences, the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health.

Financial Support and sponsorship:

This work was supported by the Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine, Eberhard-Karls University Tuebingen, Germany (BA) and McLean Hospital, Belmont, MA 024784, Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02215, USA (UR).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest:

In the last three years, UR has received compensation for professional services from Concert Pharmaceuticals. BA declares that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Olsen RW. Analysis of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) type A receptor subtypes using isosteric and allosteric ligands. Neurochem Res. 2014;39:1924–1941. doi: 10.1007/s11064-014-1382-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grasshoff C, Drexler B, Rudolph U, Antkowiak B. Anaesthetic drugs: linking molecular actions to clinical effects. Curr Pharm Des. 2006;12:3665–3679. doi: 10.2174/138161206778522038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rudolph U, Knoflach F. Beyond classical benzodiazepines: novel therapeutic potential of GABAA receptor subtypes. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:685–697. doi: 10.1038/nrd3502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fritschy JM, Brunig I. Formation and plasticity of GABAergic synapses: physiological mechanisms and pathophysiological implications. Pharmacol Ther. 2003;98:299–323. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(03)00037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonin RP, Orser BA. GABAA receptor subtypes underlying general anesthesia. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;90:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paul SM, Doherty JJ, Robichaud AJ, et al. The major brain cholesterol metabolite 24(S)-hydroxycholesterol is a potent allosteric modulator of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors. J Neurosci. 2013;33:17290–17300. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2619-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perouansky M, Pearce RA. How we recall (or don’t): the hippocampal memory machine and anesthetic amnesia. Can J Anesth. 2011;58:157–166. doi: 10.1007/s12630-010-9417-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caraiscos VB, Newell JG, You T, et al. Selective enhancement of tonic GABAergic inhibition in murine hippocampal neurons by low concentrations of the volatile anesthetic isoflurane. J Neurosci. 2004;24:8454–8458. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2063-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng VY, Martin LJ, Elliott EM, et al. Alpha5GABAA receptors mediate the amnestic but not sedative-hypnotic effects of the general anesthetic etomidate. J Neurosci. 2006;26:3713–3720. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5024-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pirker S, Schwarzer C, Wieselthaler A, et al. GABAA receptors: immunocytochemical distribution of 13 subunits in the adult rat brain. Neuroscience. 2000;101:815–850. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00442-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sur C, Fresu L, Howell O, et al. Autoradiographic localization of alpha5 subunit-containing GABAA receptors in rat brain. Brain Res. 1999;822:265–270. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01152-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin LJ, Oh GHT, Orser BA. Etomidate Targets alpha(5) gamma-Aminobutyric Acid Subtype A Receptors to Regulate Synaptic Plasticity and Memory Blockade. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:1025–1035. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181bbc961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodgers FC, Zarnowska ED, Laha KT, et al. Etomidate Impairs Long-Term Potentiation In Vitro by Targeting alpha5-Subunit Containing GABAA Receptors on Nonpyramidal Cells. J Neurosci. 2015;35:9707–9716. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0315-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jurd R, Arras M, Lambert S, et al. General anesthetic actions in vivo strongly attenuated by a point mutation in the GABAA receptor beta 3 subunit. FASEB J. 2003;17:250–252. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0611fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zarnowska ED, Rodgers FC, Oh I, et al. Etomidate blocks LTP and impairs learning but does not enhance tonic inhibition in mice carrying the N265M point mutation in the beta3 subunit of the GABAA receptor. Neuropharmacology. 2015;93:171–178. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knabl J, Witschi R, Hosl K, et al. Reversal of pathological pain through specific spinal GABAA receptor subtypes. Nature. 2008;451:330–334. doi: 10.1038/nature06493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paul J, Yevenes GE, Benke D, et al. Antihyperalgesia by alpha2-GABAA receptors occurs via a genuine spinal action and does not involve supraspinal sites. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39:477–487. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18**.Ralvenius WT, Benke D, Acuna MA, et al. Analgesia and unwanted benzodiazepine effects in point-mutated mice expressing only one benzodiazepine-sensitive GABAA receptor subtype. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6803. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7803. This comprehensive work provides evidence that positive allosteric modulation of α2-GABAA receptors reduces chronic pain but does neither cause sedation nor the development of tolerance. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Besson M, Matthey A, Daali Y, et al. GABAergic modulation in central sensitization in humans: a randomized placebo-controlled pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic study comparing clobazam with clonazepam in healthy volunteers. Pain. 2015;156:397–404. doi: 10.1097/01.j.pain.0000460331.33385.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20**.Zurek AA, Yu J, Wang DS, et al. Sustained increase in alpha5GABAA receptor function impairs memory after anesthesia. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:5437–5441. doi: 10.1172/JCI76669. In this study GABAA receptor trafficking was altered up to one week after animals received a single of etomidate, resulting in memory dysfunction. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Y, Wu Y, Li R, et al. Propofol Regulates the Surface Expression of GABAA Receptors: Implications in Synaptic Inhibition. Anesth Analg. 2015;121:1176–1183. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levi S, Le RN, Eugene E, Poncer JC. Benzodiazepine ligands rapidly influence GABAA receptor diffusion and clustering at hippocampal inhibitory synapses. Neuropharmacology. 2015;88:199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jacob TC, Michels G, Silayeva L, et al. Benzodiazepine treatment induces subtype-specific changes in GABAA receptor trafficking and decreases synaptic inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:18595–18600. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204994109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dantzer R, O’Connor JC, Freund GG, et al. From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:46–56. doi: 10.1038/nrn2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yirmiya R, Goshen I. Immune modulation of learning, memory, neural plasticity and neurogenesis. Brain Behav Immun. 2011;25:181–213. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gofton TE, Young GB. Sepsis-associated encephalopathy. Nat Rev Neurol. 2012;8:557–566. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang DS, Zurek AA, Lecker I, et al. Memory deficits induced by inflammation are regulated by alpha5-subunit-containing GABAA receptors. Cell Rep. 2012;2:488–496. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28*.Avramescu S, Wang DS, Lecker I, et al. Inflammation Increases Neuronal Sensitivity to General Anesthetics. Anesthesiology. 2016;124:417–427. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000943. An explanation is provided why the sensitivity to anesthetic agents is increased in patients suffering from systemic inflammation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hyder AA, Wunderlich CA, Puvanachandra P, et al. The impact of traumatic brain injuries: a global perspective. Neuro Rehabilitation. 2007;22:341–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thal SC, Timaru-Kast R, Wilde F, et al. Propofol impairs neurogenesis and neurologic recovery and increases mortality rate in adult rats after traumatic brain injury. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:129–141. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182a639fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31*.Drexel M, Puhakka N, Kirchmair E, et al. Expression of GABA receptor subunits in the hippocampus and thalamus after experimental traumatic brain injury. Neuropharmacology. 2015;88:122–133. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.08.023. This work shows that traumatic brain injury strongly decreases mRNAs of many GABAA receptor subunits suggesting a general decrease in GABAA receptor-mediated inhibition. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gyermek L, Soyka LF. Steroid anesthetics. Anesthesiology. 1975;42:331–344. doi: 10.1097/00000542-197503000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Belelli D, Lambert JJ. Neurosteroids: endogenous regulators of the GABAA receptor. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:565–575. doi: 10.1038/nrn1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schumacher M, Mattern C, Ghoumari A, et al. Revisiting the roles of progesterone and allopregnanolone in the nervous system: resurgence of the progesterone receptors. Prog Neurobiol. 2014;113:6–39. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rupprecht R, Papadopoulos V, Rammes G, et al. Translocator protein (18 kDa) (TSPO) as a therapeutic target for neurological and psychiatric disorders. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:971–988. doi: 10.1038/nrd3295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li P, Bracamontes JR, Manion BD, et al. The neurosteroid 5beta-pregnan-3alpha-ol-20-one enhances actions of etomidate as a positive allosteric modulator of alpha1beta2gamma2L GABAA receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2014;171:5446–5457. doi: 10.1111/bph.12861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37*.Goodchild CS, Serrao JM, Kolosov A, Boyd BJ. Alphaxalone Reformulated: A Water-Soluble Intravenous Anesthetic Preparation in Sulfobutyl-Ether-beta-Cyclodextrin. Anesth Analg. 2015;120:1025–1031. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000559. This work together with Monagle J and coworkers 2015 suggests that the use of neuroactive steroids for providing anesthsia is expected to reduce cardiovascular and respiratory side effects. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Monagle J, Siu L, Worrell J, et al. A Phase 1c Trial Comparing the Efficacy and Safety of a New Aqueous Formulation of Alphaxalone with Propofol. Anesth Analg. 2015;121:914–924. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saab BJ, Maclean AJ, Kanisek M, et al. Short-term memory impairment after isoflurane in mice is prevented by the alpha5 gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor inverse agonist L-655,708. Anesthesiology. 2010;113:1061–1071. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181f56228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Uusi-Oukari M, Korpi ER. Regulation of GABAA receptor subunit expression by pharmacological agents. Pharmacol Rev. 2010;62:97–135. doi: 10.1124/pr.109.002063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Serantes R, Arnalich F, Figueroa M, et al. Interleukin-1beta enhances GABAA receptor cell-surface expression by a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway: relevance to sepsis-associated encephalopathy. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:14632–14643. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512489200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rudolph U, Mohler H. GABAA receptor subtypes: Therapeutic potential in Down syndrome, affective disorders, schizophrenia, and autism. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2014;54:483–507. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-011613-135947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Drexel M, Kirchmair E, Sperk G. Changes in the expression of GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs in parahippocampal areas after kainic acid induced seizures. Front Neural Circuits. 2013;7:142. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2013.00142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cellot G, Cherubini E. Functional role of ambient GABA in refining neuronal circuits early in postnatal development. Front Neural Circuits. 2013;7:136. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2013.00136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stojanovic T, Capo I, Aronica E, et al. The alpha1, alpha2, alpha3, and gamma2 subunits of GABA receptors show characteristic spatial and temporal expression patterns in rhombencephalic structures during normal human brain development. J Comp Neurol. 2015 doi: 10.1002/cne.23923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ferando I, Mody I. Altered gamma oscillations during pregnancy through loss of delta subunit-containing GABAA receptors on parvalbumin interneurons. Front Neural Circuits. 2013;7:144. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2013.00144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Olsen RW, Sieghart W. International Union of Pharmacology. LXX. Subtypes of gamma-aminobutyric acid(A) receptors: classification on the basis of subunit composition, pharmacology, and function. Update Pharmacol Rev. 2008;60:243–260. doi: 10.1124/pr.108.00505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rudolph U, Crestani F, Benke D, et al. Benzodiazepine actions mediated by specific gamma-aminobutyric acid(A) receptor subtypes. Nature. 1999;401:796–800. doi: 10.1038/44579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reynolds DS, Rosahl TW, Cirone J, et al. Sedation and anesthesia mediated by distinct GABAA receptor isoforms. J Neurosci. 2003;23:8608–8617. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-24-08608.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Löw K, Crestani F, Keist R, et al. Molecular and neuronal substrate for the selectice attenuation of anxiety. Science. 2000;290:131–134. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5489.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]